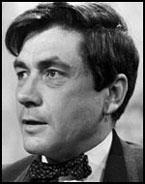

Robert Kee

Robert Kee was born in Calcutta, India, on 5th October, 1919. His father was a successful jute trader. However, he lost his business in the Great Depression and the family was forced to return to Britain. Denis Barker has pointed out: "He received a payoff of £900 and no pension, forcing him to work at various makeshift jobs until he was 74. In speaking and writing about his father, Robert showed far more than usual emotion. All this might have created a reach-me-down revolutionary. With him, it led to an icy determination to pursue the truth wherever it might lie."

Kee won a scholarship to Stowe School before being awarded an exhibition to study history at Magdalen College, Oxford under A.J.P. Taylor. The two men became close friends. According to his autobiography, A Personal History (1983), Taylor's wife fell in love with Kee: "Margaret was falling passionately, unrestrainly in love with Robert. On the only occasion she discussed the affair with me many years later, she said it was because she expected him to be killed in the coming war. Maybe so or maybe a woman in love will say anything. Robert, who certainly knew he was attractive to women, hardly noticed what was going on and probably thought it would all be over with the summer."

After graduating from from university he joined the Royal Air Force. During the Second World War he was shot down over German-occupied Netherlands. He was imprisoned but made several attempts to escape from his Prisoner of War Camp. He finally succeeded and then made a difficult journey across Poland. He later wrote that it was "all rather fun", and that having attended an English public school was good training for survival in a prison camp.

On his return to London he began an affair with Janetta Sinclair-Loutit, the wife of Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, the Director of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in Belgrade. Sinclair-Loutit later recalled: "She (Janetta) was courageously honest; suddenly we were both aghast at the ruin of it all.... I knew that Janetta had never told me a lie, her honesty had always been total and it was one of my reasons for loving her. It seems that only a few weeks before my getting back to London she had met someone who had become so important to her that only an act of self-blinding would allow me to count on her reactions continuing to be those which I had known so well. She was sad about this but there it was. He was no one I knew. He was an RAF ex-POW called Robert Kee."

Kee married Janetta in 1947 but divorced three years later. Later that year Kee published a novel A Crowd is Not Company about a RAF pilot who escaped from a Prisoner of War Camp in Poland. Based on his own experiences it was later republished as an autobiography. He also published the novels, The Impossible Shore (1949) and A Sign of the Times (1955).

Kee also worked as a journalist for Picture Post (1948-51), The Observer (1956-57), The Sunday Times (1957-58) and the BBC (1958-62). This included several Panorama documentaries. Kee wrote several history books on Ireland including The Green Flag (1972) and Ireland: A History (1980). Denis Barker has commented: "His passion for justice, exercised on subjects such as Ireland or British Asian immigrants, was always tempered by his objective sense that both sides of a question must be ventilated. He seemed increasingly a throwback once more raucous and less scrupulous voices had become fashionable in the media. He did not look a populist, and was not, either as a documentary maker or as the author of many books of history. The finely chiselled, rather saturnine features and piercing eyes were those of a colonial magistrate rather than a bland television personality."

Kee also wrote and presented the documentary series Ireland - A Television History in 1980. The Daily Telegraph reported: "The series was an expositional exercise in which Kee led viewers on a spirited tour of 800 years of hostilities between Ireland and England, relating contemporary troubles to the history out of which they grew. It was a courageous venture, both because of the controversial nature of the subject and because it was produced at a time when it was generally accepted that a headline about Northern Ireland on a newspaper front page was enough to leave a dent in the daily sales figures. When it was broadcast in 1980-81, however, the series proved unexpectedly timely and popular, since it coincided with rising tensions in Northern Ireland and the start of the hunger strikes in the Maze prison which catapulted Irish history back into the heart of British politics."

In February 1983 Kee joined forces with David Frost, Anna Ford, Michael Parkinson and Angela Rippon to establish TV-am. The venture was not a great success and closed down in December 1992. From 1984 to 1988 he worked for Channel 4’s Seven Days series.

Other books by Robert Kee includes 1945 - The World We Fought For (1985), Trial and Error: Maguires, the Guildford Pub Bombings and British Justice (1986), Parnell and Irish Nationalism (1993) and World We Left Behind: Chronicle of the Year 1939 (1993).

Robert Kee died on 11th January, 2013.

Primary Sources

(1) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

I knew that Janetta had moved the few hundred yards from our Park Road flat to the Sussex Place house we were planning to share with Cyril Connolly. It was in a Nash Terrace with its own gardens directly facing Regent's Park. It was an enchantment to see it because it was exactly the sort of London home of which I had always dreamed. Cyril was already installed on the piano nobile. Our daughter was very smiling and, no matter what she was doing, seemed consumed with pleasure. The whole place had a charm that made me realise what I had been missing. Janetta and I had corresponded about moving house and I had signed some papers to help buy the remainder of the Crown lease, but the real nature of the move had not yet sunk into my Balkan-oriented head.

There was certainly a welcome, but in it something was missing. Janetta said right away that she would come out to Belgrade to give it a try but that she did not think she should start by bringing our daughter. She was not at all convinced that our partnership could still work. She was courageously honest; suddenly we were both aghast at the ruin of it all. Somehow the house no longer seemed to be something that we had created together. The whole basis of our joint life lay in its free consent. Obligation had nothing to do with it. She said that only the value of the past had made her feel obliged to try to re-start with me; it became more and more obvious that her present life brought with it an impulsion in exactly the opposite sense. I knew that Janetta had never told me a lie, her honesty had always been total and it was one of my reasons for loving her.

It seems that only a few weeks before my getting back to London she had met someone who had become so important to her that only an act of self-blinding would allow me to count on her reactions continuing to be those which I had known so well. She was sad about this but there it was. He was no one I knew. He was an RAF ex-POW called Robert Kee.

The plain fact that my personal life at home had failed as rapidly, and as completely, as my working life overseas had succeeded was something that I had totally failed to anticipate - I had even been thinking that the one would enhance the other. In the past Janetta and I had never felt any need for self questioning, or for questioning each other. Our agreement had been automatic and natural. Which ever way we looked at things, and we were certainly very different, we had always ended up with a common accord until that one day when I, without consultation, had accepted Sir Victor Richardson's offer to send me overseas.

(2) Robert Kee, Picture Post (3rd July, 1948)

Although there are no official figures, the coloured population of Great Britain is estimated by both the Colonial Office and the League of Coloured People at about 25,000, including students. This total is distributed over the whole of Britain, but there are two large concentrated communities: one of about 7000 in the dock area of Cardiff round London Square, popularly known as 'Tiger Bay', and the other of about 8000 in the shabby mid-nineteenth century residential South End of Liverpool. It is most important to remember that all colonial coloured people, of whatsoever origin or class, have been brought up to think of Britain as 'The Mother Country'. This is particularly true of the West Indians, who no longer have the tribal associations and native language which can still provide some fundamental security for the disillusioned African. The West Indian disillusioned with Britain is deprived of all sense of security. He becomes, quite understandably, the most sensitive and neurotic member of the coloured community.

For Britain's colour problem there are a few practical and remedial steps that can be taken. But it can only be solved By a true integration of white and coloured people in one society. And for that to take place there must be some sort of revolution inside every individual mind - coloured and white - where prejudices based on bitterness, ignorance or patronage have been established.

(3) Denis Barker, The Guardian (11th January, 2013)

His passion for justice, exercised on subjects such as Ireland or British Asian immigrants, was always tempered by his objective sense that both sides of a question must be ventilated. He seemed increasingly a throwback once more raucous and less scrupulous voices had become fashionable in the media.

He did not look a populist, and was not, either as a documentary maker or as the author of many books of history. The finely chiselled, rather saturnine features and piercing eyes were those of a colonial magistrate rather than a bland television personality.

(4) The Daily Telegraph (15th January, 2013)

In the late 1970s he embarked on a major 12-part BBC series, Ireland: A Television History. Broadcast in 1980, and accompanied by a lively and lavishly illustrated book, the series was an expositional exercise in which Kee led viewers on a spirited tour of 800 years of hostilities between Ireland and England, relating contemporary troubles to the history out of which they grew.

It was a courageous venture, both because of the controversial nature of the subject and because it was produced at a time when it was generally accepted that a headline about Northern Ireland on a newspaper front page was enough to leave a dent in the daily sales figures.

When it was broadcast in 1980-81, however, the series proved unexpectedly timely and popular, since it coincided with rising tensions in Northern Ireland and the start of the hunger strikes in the Maze prison which catapulted Irish history back into the heart of British politics.

It also scored a notable coup when the Republic of Ireland broadcaster and co-producer RTE screened the last two episodes uncut, despite the fact that they contained statements from organisations banned in that country.

Kee’s aim was not to spark debate among historians and politicians, but to give a largely ignorant British audience its first detailed insight into the history of Irish politics — especially the issues surrounding sovereignty and identity. Whether success was ever a real possibility is doubtful, as media coverage associated with Ireland quickly reverted to banner headlines with the death of hunger striker Bobby Sands and the restoration of the IRA’s bombing campaign in London. But the series won Kee well-deserved accolades, including the Ewart-Biggs Memorial Prize.