The Great Depression

One way of making money during the 1920's was to buy stocks and shares. Prices of these stocks and shares constantly went up and so investors kept them for a short-term period and then sold them at a good profit. As with consumer goods, such as motor cars and washing machines, it was possible to buy stocks and shares on credit. This was called buying on the "margin" and enabled "speculators" to sell off shares at a profit before paying what they owed. In this way it was possible to make a considerable amount of money without a great deal of investment. During the first week of December, 1927, "more shares of stock had changed hands than in any previous week in the whole history of the New York Stock Exchange." (1)

The share price of Montgomery Ward, the mail-order company, went from $132 on 3rd March, 1928, to $466 on 3rd September, 1928. Whereas Union Carbide & Carbon for the same period went from $145 to $413; American Telephone & Telegraph from $77 to $181; Westinghouse Electric Corporation from $91 to $313 and Anaconda Copper from $54 to $162. (2)

John J. Raskob, a senior executive at General Motors, published an article, Everybody Ought to be Rich in August, 1929, where he pointed out: "The common stocks of their country have in the past ten years increased enormously in value because the business of the country has increased. Ten dollars invested ten years ago in the common stock of General Motors would now be worth more than a million and a half dollars. And General Motors is only one of may first-class industrial corporations." He then went on to say: "If a man saves $15 a week, and invests in good common stocks, and allows the dividends and rights to accumulate, at the end of twenty years he will have at least $80,000 and an income from investments of around $400 a month. He will be rich. And because income can do that, I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich, but ought to be rich." (3)

Cecil Roberts, a British journalist working in the United States, pointed out that the stock market hysteria reached its apex in the summer of 1929. "Everyone gave you tips for a rise. Every was playing the market. Stocks soared dizzily. I found it hard not to be engulfed. I had invested my American earnings in good stocks. Should I sell for a profit? Everyone said, 'Hang on - it's a rising market'. On my last day in New York I went down to the barber. As he removed the sheet he said softly, 'Buy Standard Gas. I've doubled. It's good for another double.' As I walked upstairs, I reflected that if the hysteria had reached the barber-level, something must soon happen." (4)

Alec Wilder, the songwriter, became concerned about the value of his shares: "I knew something was terribly wrong because I heard bellboys, everybody, talking about the stock market. In August 1929 I persuaded my mother in Rochester to let me talk to our family adviser. I wanted to sell stock which had been left me by my father.... I talked to this charming man and told him I wanted to unload this stock. Just because I had this feeling of disaster. He got very sentimental: 'Oh your father wouldn't have liked you to do that.' He was so persuasive, I said O.K. I could have sold it for $160,000. Four years later, I sold it for $4,000." (5)

On 3rd September 1929 the stock market reached an all-time high. In the weeks that followed prices began to slowly decline. Later that month, an incident took place in London that caused major problems on Wall Street. In April 1929 Clarence Hatry, the former owner of Leyland Motors, acquired control of United Steel by borrowing "£789,000 from banks on the security of forged Corporation and General scrip certificates ascribed to the municipalities of Gloucester, Wakefield, and Swindon. £822,000 was withheld from these three corporations and another £700,000 was raised by duplicating shares in other companies he had promoted. As rumours about the Hatry companies circulated in the City, he spent large sums vainly trying to support their share values." (6)

On 20th September Hatry voluntarily confessed his frauds to Sir Archibald Bodkin, director of public prosecutions. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith, described Hatry as "one of those curiously un-English figures with whom the English periodically find themselves unable to cope." (7) The news of this corrupt activity caused the London Stock Exchange to crash. This greatly weakened the optimism of American investment in markets overseas and caused further falls in the value of shares on Wall Street. (8)

Efforts were made to regain confidence in the state of the American economy. Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, was considered the most important economist of the 1920s. His research on the quantity theory of money inaugurated the school of macroeconomic thought known as monetarism. On 17th October, 1929 he was reported as telling the Purchasing Agents Association that stock prices had reached "what looks like a permanently high plateau". He added that he expected to see the stock market, within a few months, "a good deal higher than it is today." (9)

Despite Fisher's prediction, on 24th October, over 12,894,650 shares were sold. Prices fell dramatically as sellers tried to find people willing to buy their shares. That evening, five of the country's bankers, led by Charles Edward Mitchell, chairman of the National City Bank, issued a statement saying that due to the heavy selling of shares, many were now under-priced. This statement failed to halt the reduction in demand for shares. (10)

The New York Times reported: "The most disastrous decline in the biggest and broadest stock market of history rocked the financial district yesterday.... It carried down with it speculators, big and little, in every part of the country, wiping out thousands of accounts. It is probable that if the stockholders of the country's foremost corporations had not been calmed by the attitude of leading bankers and the subsequent rally, the business of the country would have been seriously affected. Doubtless business will feel the effects of the drastic stock shake-out, and this is expected to hit the luxuries most severely." (11)

On the opening of the Wall Street Stock Exchange on 29th October, 1929, John D. Rockefeller, the American oil industry business magnate and successful industrialist, issued a statement which attempted to regain confidence in the state of the economy: "Believing that fundamental conditions of the country are sound and that there is nothing in the business situation to warrant the destruction of values that has taken place on the exchanges during the past week, my son and I have for some days been purchasing sound common stocks." (12)

cities and they cannot be sure of a roof over their own heads."

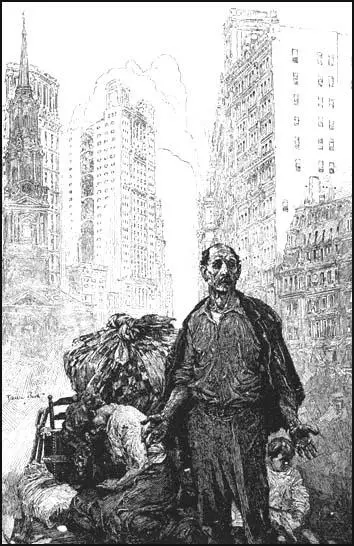

Franklin Booth, The Unemployed (February, 1931)

This did not have the desired impact on the market for that day over 16 million shares were sold. The market had lost 47 per cent of its value in twenty-six days. "Efforts to estimate yesterday's market losses in dollars are futile because of the vast number of securities quoted over the counter and on out-of-town exchanges on which no calculations are possible. However, it was estimated that 880 issues, on the New York Stock Exchange, lost between $8,000,000,000 and $9,000,000,000 yesterday. Added to that loss is to be reckoned the depreciation on issues on the Curb Market, in the over the counter market and on other exchanges." (13)

Although less than one per cent of the American people actually possessed stocks and shares, the Wall Street Crash was to have a tremendous impact on the whole population. The fall in share prices made it difficult for entrepreneurs to raise the money needed to run their companies. Frederick Lewis Allen pointed out: "Billions of dollars' of profits - and paper profits - had disappeared. The grocer, the window-cleaner, and the seamstress had lost their capital. In every town there were families which had suddenly dropped from showy affluence into debt. Investors who had dreamed of retiring to live on their fortunes now found themselves back once more at the very beginning of the long road to riches. Day by day the newspapers printed the grim reports of suicides." (14)

Within a short time, 100,000 American companies were forced to close and consequently many workers became unemployed. As there was no national system of unemployment benefit, the purchasing power of the American people fell dramatically. This in turn led to even more unemployment. Yip Harburg pointed out that before the Wall Street Crash, the American citizen thought: "We were the prosperous nation, and nothing could stop us now.... There was a feeling of continuity. If you made it, it was there forever. Suddenly the big dream exploded. The impact was unbelievable." (15)

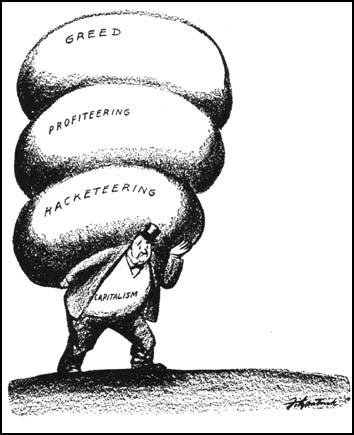

It was later discovered that some Wall Street bankers had been partly responsible for the crash. It was pointed out that from September 1929, Albert H. Wiggin had begun selling short his personal shares in Chase National Bank at the same time he was committing his bank's money to buying. As Michael Perino pointed out: "In the midst of the 1929 crash, Wiggen was part of the group of Wall Street leaders who tried to prop up the market. Or at least that was what the public thought.... Wiggen was actually shorting Chase's stock (in effect betting that the price of the stock would continue to drop) on money borrowed from Chase". He shorted over 42,000 shares, earning him over $4 million. His earning were tax-free since he used a Canadian shell company to buy the stocks. (16)

As William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963) pointed out: "At a time when millions lived close to starvation, and some even had to scavenge for food, bankers like Wiggin and corporation executives like George Washington Hill of American Tobacco drew astronomical salaries and bonuses. Yet many of these men, including Wiggin, manipulated their investments so that they paid no income tax at all. In Chicago, where teachers, unpaid for months, fainted in classrooms for want of food, wealthy citizens of national reputation brazenly refused to pay taxes or submitted falsified statements." (17)

Senator Burton Wheeler of Montana argued: "The best way to restore confidence in the bank would be to take these crooked presidents out of the banks and treat them the same way as we treated Al Capone when he failed to pay his income-tax." Senator Carter Glass of Virginia joked in bad taste: "There is a big scandal down in Georgia. The fact has just been discovered that a white woman is married to a banker." He added that in his state people usually lynched black men, but now they were "lynching bankers." (18)

After the Wall Street Crash, the leading utility magnate, Samuel Insull, fled the United States to France. Insull was the chairman of the boards of sixty-five companies that folded, wiping out the life savings of 600,000 shareholders. When the United States asked French authorities that he be extradited, Insull moved on to Greece, where there was not yet an extradition treaty with the United States. He later moved to Turkey where he was arrested and extradited back to the United States. He was defended by famous Chicago lawyer Floyd Thompson and found not guilty on all counts. (19)

Unemployment

In 1929 only 1.5 million people in the United States were out of work; by 1931 it had reached 8 million. In many areas the situation was even worse than these figures imply. In industrial cities like Chicago, for example, over 40% of the work-force was unemployed. Edmund Wilson observed: "There is not a garbage-dump in Chicago which is not diligently haunted by the hungry. Last summer the hot weather when the smell was sickening and the flies were thick, there were a hundred people a day coming to one of the dumps... a widow who used to do housework and laundry, but now had no work at all, fed herself and her fourteen-year-old son on garbage. Before she picked up the meat, she would always take off her glasses so that she couldn't see the maggots." (20)

At first President Herbert Hoover refused to take action, claiming that it was only a temporary problem that American businessmen would eventually solve. Hoover then decided to take dramatic action. He authorized the Mexican Repatriation program to force unemployed Mexican citizens to return home. Estimates of how many were repatriated range from 500,000 to 2,000,000, of whom perhaps 60% were US citizens by birth. As the forced migration was based on race, and ignored citizenship, Kevin Johnson has argued that today this policy would be classified as a form of "ethnic cleansing." (21)

In 1930 President Hoover attempted to give businessmen some help by raising custom duties to record levels. Europe retaliated by increasing its custom duties and this resulted in a further decline in world trade. By 1932 the number of people unemployed reached 12 million. America was in a deep depression and the Hoover administration seemed to have little idea how to solve it. These actions lost Hoover the support of progressive Republicans such as William Borah and undermined his authority in the party. (22)

Temporary Emergency Relief Administration

Franklin Roosevelt, the Governor of New York, had opposed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. He also disagreed with Hoover when he vetoed a bill that would have created a federal unemployment agency. Hoover also opposed a plan to create a public works programme. In March, 1930, Roosevelt established a commission to stabilize employment in New York. "The situation is serious and the time has come for us to face this unpleasant fact dispassionately". (23)

Unemployment which stood at 4 million in March 1930, reached 8 million in March 1931. Hoovervilles, settlements on tin shacks, abandoned cars and discarded packing crates, emerged on the edges of all big cities. President Hoover responded by urging Americans to embrace the principles of local responsibility and mutual self-help, by setting up community soup kitchens. If we depart from these principles, he argued, we will "have struck at the roots of self-government". (24)

Roosevelt made it clear that he disapproved of this approach to unemployment. He pointed out he was willing to spend $20 million to provide useful work where possible and, where such work could not be found, to provide the needy with food and shelter. "In broad terms I assert that modern society, acting through its government, owes the definite obligation to prevent the starvation or dire want of any of its fellow men and women who try to maintain themselves but cannot... To these unfortunate citizens aid must be extended by government - not as a matter of charity but as a matter of social duty." (25)

In addition to the $20 million relief package, Roosevelt asked the New York legislature, for funds to establish a new state agency, the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA), to distribute the funds. He also requested that the legislature to raise personal income taxes by 50% to pay for the relief effort. New York was the first state to establish a relief agency, and TERA immediately became a model for other states. This included New Jersey, Rhode Island and Illinois. (26)

Roosevelt selected Jesse Straus, president of R. H. Macy department stores, and one of the most respected businessmen in New York, to head TERA. He chose as his executive director a forty-two-year-old social worker, Harry L. Hopkins, who at that time was unknown to Roosevelt or any of his advisers. Hopkins was an inspired choice. A gifted administrator who proved he could deliver aid swiftly. In the next six years TERA assisted some 5 million people - 40 per cent of the population of New York State. (27)

Eleanor Roosevelt pointed out that TERA was the first of her husband's important projects. "Many experiments that were later to be incorporated into a national program were being tried out in the state. It was part of Franklin's political philosophy that the great benefit to be derived from having forty-eight states was the possibility of experimenting on a small scale to see how a program worked before trying it out nationally." (28)

Senior members of the Democratic Party began to talk of Roosevelt being the best man to take on Herbert Hoover in the 1932 Presidential Election. This included Burton Wheeler of Montana, Cordell Hull of Tennessee, James F. Byrnes of South Carolina and Pat Harrison of Mississippi. Roosevelt wrote to his friend, James Hoey, that "the great majority of States through their regular organizations are showing every friendliness towards me." (29)

1932 Presidential Election

Franklin D. Roosevelt made twenty-seven major addresses during the six month 1932 Presidential Election campaign, each devoted to a single subject. He spoke briefly on thirty-two additional occasions, usually at whistle-stops or impromptu gatherings to which he was invited. Herbert Hoover, by contrast, made only ten speeches, all of which were delivered during the closing weeks of the campaign. (30)

At a meeting in Detroit, President Hoover told the audience, "I wish to present to you the evidence that the measures and the policies of the Republican administration are winning this major battle for recovery. And we are taking care of distress in the meantime. It can be demonstrated that the tide has turned and the gigantic forces of depression are today in retreat." (31) The crowd responded with the cry: "Down with Hoover, slayer of veterans". According to one observer: "When he got up to speak, his face was ashen, his hands trembled. Toward the end, Hoover was a pathetic figure, a weary, beaten man, often jeered by crowds as a President had never been jeered before." (32)

The British film-star, Charlie Chaplin, took a keen interest in the election and later commented: "The lugubrious Hoover sat and sulked, because his disastrous economic sophistry of allocating money at the top in the belief that it would percolate down to the common people had failed. And amidst all this tragedy he ranted in the election campaign that if Franklin Roosevelt got into office the very foundations of the American system - not an infallible system at that moment - would be imperilled." (33)

On 31st October, 1932, in a speech in New York City Hoover attempted to show the American public had a clear choice in the election: "This campaign is more than a contest between two men. It is more than a contest between two parties. It is a contest between two philosophies of government. We are told by the opposition that we must have a change, that we must have a new deal.... This question is the basis upon which our opponents are appealing to the people in their fear and their distress. They are proposing changes and so-called new deals which would destroy the very foundations of the American system of life."

Hoover went on to argue: "The proposals of our opponents will endanger or destroy our system. I especially emphasize that promise to promote 'employment for all surplus labour at all times.' At first I could not believe that anyone would be so cruel as to hold out hope so absolutely impossible of realization to these 10,000,000 who are unemployed. And I protest against such frivolous promises being held out to a suffering people. If it were possible to give this employment to 10,000,000 people by the Government, it would cost upwards of $9,000,000,000 a year. It would pull down the employment of those who are still at work by the high taxes and the demoralization of credit upon which their employment is dependent. It would mean the growth of a fearful bureaucracy which, once established, could never be dislodged." (34)

Roosevelt heard Hoover's speech on the radio before appearing in Boston that night: "Once more he warned the people against changing - against a new deal - stating that it would mean changing the fundamental principles of America, what he called the sound principles that have been so long believed in in this country. My friends, my New Deal does not aim to change those principles. Secure in their undying belief in their great tradition and in the sanctity of a free ballot, the people of this country - the employed, the partially employed and the unemployed, those who are fortunate enough to retain some of the means of economic well-being, and those from whom these cruel conditions have taken everything - have stood with patience and fortitude in the face of adversity."

Roosevelt highlighted the plight of the unemployed: "There they stand. And they stand peacefully, even when they stand in the breadline. Their complaints are not mingled with threats. They are willing to listen to reason at all times. Throughout this great crisis the stricken army of the unemployed has been patient, law-abiding, orderly, because it is hopeful. But, the party that claims as its guiding tradition the patient and generous spirit of the immortal Abraham Lincoln, when confronted by an opposition which has given to this Nation an orderly and constructive campaign for the past four months, has descended to an outpouring of misstatements, threats and intimidation. The Administration attempts to undermine reason through fear by telling us that the world will come to an end on November 8th if it is not returned to power for four years more. Once more it is a leadership that is bankrupt, not only in ideals but in ideas." (35)

During the campaign Herbert Hoover had to have a heavy police escort to protect him from the angry crowds. He became very unpopular when he told one of the most influential journalists in Washington, Raymond Clapper: "Nobody is actually starving. The hobos, for example, are better fed than they have ever been." In another interview he attributed the high unemployment rate to the fact that "many people have left their jobs for the more profitable one of selling apples." (36)

Three days before the election he claimed that Roosevelt's policies could be compared to those of Joseph Stalin. He suggested that his opponent had "the same philosophy of government which has poisoned all of Europe... the fumes of the witch's cauldron which boiled in Russia." He accused the Democrats of being "the party of the mob". Hoover then added: "Thank God, we still have a government in Washington that knows how to deal with the mob." (37)

The turnout, almost 40 million, was the largest in American history. Roosevelt received 22,825,016 votes to Hoover's 15,758,397. With a 472-59 margin in the Electoral College, he captured every state south and west of Pennsylvania. Roosevelt carried more counties than a presidential candidate had ever won before, including 282 that had never gone Democratic. Of the forty states in Hoover's victory coalition four years before, the President held but six. Hoover received 6 million fewer votes than he had in 1928. The Democrats gained ninety seats in the House of Representatives to give them a large majority (310-117) and won control of the Senate (60-36). Only one previous Republican candidate, William Howard Taft, had done as badly as Hoover. (38)

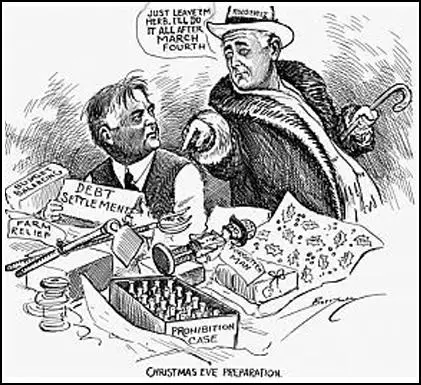

all after March 4th." Cliff Berryman, Washington Evening Star (December, 1932)

Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected on 8th November, 1932, but the inauguration was not until 4th March, 1933. While he waited to take power, the economic situation became worse. Three years of depression had cut national income in half. Five thousand bank failures had wiped out 9 million savings accounts. By the end of 1932, 15 million workers, one out of every three, had lost their jobs. When the Soviet Union's trade office in New York issued a call for 6,000 skilled workers to go to Russia, more than 100,000 applied. (39)

Edmund Wilson published an article in The New Republic just before Roosevelt took office: "There is not a garbage-dump in Chicago which is not diligently haunted by the hungry. Last summer, the hot weather when the smell was sickening and the flies were thick, there were a hundred people a day coming to one of the dumps... a widow who used to do housework and laundry, but now had no work at all, fed herself and her fourteen-year-old son on garbage. Before she picked up the meat, she would always take off her glasses so that she couldn't see the maggots." (40)

Primary Sources

(1) John J. Raskob, Everybody Ought to be Rich (June, 1929)

If a man saves $15 a week, and invests in good common stocks, and allows the dividends and rights to accumulate, at the end of twenty years he will have at least $80,000 and an income from investments of around $400 a month. He will be rich. And because income can do that, I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich, but ought to be rich.

(2) Alec Wilder was interviewed by Studs Terkel in Hard Times (1970)

I knew something was terribly wrong because I heard bellboys, everybody, talking about the stock market. About six weeks before the Wall Street Crash, I persuaded my mother in Rochester to let me talk to our family adviser. I wanted to sell stock which had been left me by my father. He got very sentimental: "Oh your father wouldn't have liked you to do that." He was so persuasive, I said O.K. I could have sold it for $160,000. Four years later, I sold it for $4,000.

(3) Peggy Terry, Kentucky, interviewed by Studs Terkel in Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970)

(My father) said: "If you think it's been rough for us, I want you to see people that really had it rough." This was in Oklahoma City, and he took us to one of the Hoovervilles, and that was the most incredible thing. Here were people living in old, rusted-out car bodies. I mean that was their home. There were people living in shacks made of orange crates. One family with a whole lot of kids were living in a piano box. This wasn't just a little section, this was maybe ton-miles wide and ten-miles long. People living in whatever they could junk together.

(4) Ward James, teacher, Wisconsin, interviewed by Studs Terkel in Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970)

I finally went on relief. It's an experience I don't want anybody to go through. ... The interview was utterly ridiculous and mortifying. In the middle of mine, a more dramatic guy than I dived from the second floor stairway, head first, to demonstrate he was gonna get relief even if he had to go to the hospital to do it.... There were questions like: Who are your friends? ... Why should anybody give you money? Why should anybody give you a place to sleep? ... I did get certified some time later. I think they paid $9 a month. I came away feeling I didn't have any business living anymore.

(5) Eileen Barth, relief case worker, interview, Studs Terkel, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970)

I'll never forget one of the first families I visited. The father was a railroad man who had lost his job. I was told by my supervisor that I really had to see the poverty. If the family needed clothing, I was to investigate how much clothing they had at hand. So I looked into this man's closet - he was a tall, grey-haired man, though not terribly old. He let me look in the closet -he was so insulted. He said, "Why are you doing this?" I remember his feeling of humiliation ... this terrible humiliation. He said, "I really haven't anything to hide, but if you really must look into it . . .". I could see he was very proud. He was so deeply humiliated. And I was, too.

(6) Franklin D. Roosevelt, speech in Boston (31st October, 1932)

We have two problems: first, to meet the immediate distress; second, to build up on a basis of permanent employment.

As to immediate relief, the first principle is that this nation, this national government, if you like, owes a positive duty that no citizen shall be permitted to starve.

In addition to providing emergency relief, the Federal Government should and must provide temporary work wherever that is possible. You and I know that in the national forests, on flood prevention, and on the development of waterway projects that have already been authorized and planned but not yet executed, tens of thousands, and even hundreds of thousands of our unemployed citizens can be given at least temporary employment.

(7) Franklin D. Roosevelt, radio broadcast, Fireside Chat (12th March, 1933)

Some of our bankers have shown themselves either incompetent or dishonest in their handling of the people's funds. They had used money entrusted to them in speculations and unwise loans. This was, of course, not true of the vast majority of our banks, but it was true in enough of them to shock the people for a time into a sense of insecurity. It was the government's job to straighten out this situation and do it as quickly as possible. And the job is being performed. Confidence and courage are the essentials in our plan. We must have faith; you must not be stampeded by rumours. We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work. Together we cannot fail.

(8) Father Charles Coughlin, radio broadcast (17th January, 1934)

President Roosevelt is not going to make a mistake, for God Almighty is guiding him. President Roosevelt has leadership, he has followers and he is the answer to many prayers that were sent up last year.

If Congress fails to carry through with the President's suggestions, I foresee a revolution far greater than the French Revolution. It is either Roosevelt or Ruin.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

The Bonus Marchers (Answer Commentary)

The Wall Street Crash (Answer Commentary)

Unemployment in the United States: 1928-1933 (Answer Commentary)

The Great Depression (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject