Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit

Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit was born in 1913. His father had worked for the East India Company and had played a major part in the creation of Port Kolkata. He wrote about his mother and father in his autobiography, Very Little Luggage: "My then widowed father had two savage bull-terriers. He was walking them in the Edinburgh Park when they started leaping up at a young woman and there was a fearsome cracking of the whip before order could be restored. It seems that the lady took all this in her stride with the end result that my father married her not too long afterwards. Consequently, two people both reared as Presbyterians, one aged twenty-three and the other a good forty years older, were married in the Catholic Church. I was to be their only child."

On the outbreak of the First World War his father retired and the family moved to Cornwall. Sinclair-Loutit recalled in his autobiography: "Even as a child of eight I was brought to feel the absence of those who had fallen in the war.... The absence of those who had not come back was a reality felt in those early twenties. Those whose wounds had left them handicapped and my own age-mates who were fatherless did not allow us to forget the war... In Cornwall, apart from my own generation, I had only been meeting frankly elderly people. Those who had fallen in 1914-18 and who would have been in their forties while I was becoming a young adult were largely missing."

In 1923 Sinclair-Loutit was sent to Ampleforth School. He later reported: "So, in those later 1920s, I went on through the school, an average student not very good at games... About 1927, I took off academically, moving up from the middle of the class to the front row. I became active in the debating and historical societies and played the bassoon in the orchestra." However, Sinclair-Loutit was expelled from school after a letter he sent to a friend, that was critical of the headmaster, was intercepted and read. As Loutit pointed out: "Anyone at a pre-war Public School had learnt to regard expulsion as a form of capital punishment. In my day, a body of opinion existed that no decent College in Oxford or Cambridge would accept an expulsee. There was no appeal, because there was no way back."

In October 1931, Sinclair-Loutit was awarded a place at Cambridge University. He went to Trinity College and later recalled: "Trinity then was, as it is today, a place of reposeful beauty. It favoured, with a total generosity, both play and intellectual work." A fellow student was Donald Mclean, who he originally met on a beach in Newquay. He joined the Trinity Boat Club where he was coached by Erskine Hamilton Childers.

Sinclair-Loutit began to take a keen interest in politics: "University undergraduates, themselves then mostly the children of prosperous families were starting to have their consciences troubled by the plight of Hunger-Marchers and of those who, by the Means Test, were forced to sell their possessions before they could obtain the meagre dole payments. It was into this atmosphere that I emerged from the cosy shelter of my Cornish life." One of the Hunger-Marches went through Cambridge. "A number were wearing their war-medals, which engendered a sense of remorse amongst those who remembered that the men who returned in 1918 had been promised a land fit for heroes to live in. Though I did not then realise it, this was my baptism into socio-political activity."

In 1934 he visited Nazi Germany with a fellow student who had been impressed with the achievements of Adolf Hitler. In his autobiography he described his friend's behaviour on the trip: "The two of us managed well enough until we got close to the newer Germany. I can still feel the surprise that shook me, in Bach's own town of Luneburg, when Matthew gave the Nazi salute on turning to leave the improvised shrine containing a bust of the recently deceased Hindenburg. It had been set up in the main square to give a secular focus to the mourning ceremonies for the Field Marshal President - the last of the Junkers. Matthew dismissed my questioning of his gesture. For him, so he said, it was a simple act of politeness like taking off one's hat when going into a church. My reply did not please him: for me the hat gesture was one of neutral respect but his salute was a gratuitous act that indicated an endorsement of the Nazi Code." While in Germany he met Truda Raabe and over the next few weeks they became close friends.

On his return to Cambridge University he became friends with Margot Heinemann, Guy Burgess, John Bernal, James Klugman, Alastair Cooke, Bernard Knox and John Cornford, who were all concerned at the growth of fascism in Italy and Germany. He also became an active opponent of Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists. He later wrote: "there was an ever increasing consensus, uniting men and women of all ages and all backgrounds, in a simple refusal of complaisance toward fascist thinking... We were ready to do something about the world we lived in, rather than to accept whatever might happen next."

Sinclair-Loutit returned to Nazi Germany the following summer to spend time with Truda Raabe. She also had a strong dislike of Adolf Hitler. She told him that the Nazi SA liked failures: "Their silly uniforms make them feel that they are a success." Her father and brother had been forced to join the Nazi Party. Loutit later wrote: " I had not become an anti-fascist in the 1930s by reading books. I had seen what Fascism was doing to people I liked. It invaded every part of their lives. Neither their work, nor their leisure nor even their home life, had remained untouched."

After completing his degree at University of Cambridge he began a medical degree at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London. Sinclair-Loutit also joined the Inter-Hospitals Socialist Society, a forum of debate on matters of social medicine. However, he decided against joining the Labour Party or the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In July 1936, Isabel Brown, at the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism in London, received a telegram from Socorro Rojo Internacional, based in Madrid, asking for help in the struggle against fascism in Spain. Brown approached the Socialist Medical Associationabout sending medical help to Republicans fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Brown contacted Hyacinth Morgan, who in turn saw Dr Charles Brook.

According to Jim Fyrth, the author of The Signal Was Spain: The Spanish Aid Movement in Britain, 1936-1939 (1986): "Morgan saw Dr Charles Brook, a general practitioner in South-East London, a member of the London County Council and founder and first Secretary of the Socialist Medical Association, a body affiliated to the Labour Party. Brook, who was a keen socialist and supporter of the people's front idea, though not sympathetic to Communism, was the main architect of the SMAC. At lunch-time on Friday 31 July, he saw Arthur Peacock, the Secretary of the National Trade Union Club, at 24 New Oxford Street. Peacock offered him a room at the club for a meeting the following afternoon, and office facilities for a committee."

At the meeting on 8th August 1936 it was decided to form a Spanish Medical Aid Committee. Dr. Christopher Addison was elected President and the Marchioness of Huntingdon agreed to become treasurer. Other supporters included Leah Manning, George Jeger, Philip D'Arcy Hart, Frederick Le Gros Clark, Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, George Lansbury, Victor Gollancz, D. N. Pritt, Archibald Sinclair, Rebecca West, William Temple, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett, Eleanor Rathbone, Julian Huxley, Harry Pollitt and Mary Redfern Davies.

Soon afterwards Sinclair-Loutit was appointed Administrator of the Field Unit that was to be sent to Spain. According to Tom Buchanan, the author of Britain and the Spanish Civil War (1997), "he disregarded a threat of disinheritance from his father to volunteer."

According to Sinclair-Loutit, the Communist Party of Great Britain played an important role in the establishment of the Spanish Medical Aid Committee. In his autobiography, Very Little Luggage, he describes being taken by Isobel Brown to be briefed by Harry Pollitt, the leader of the CPGB. However, Sinclair-Loutit insisted: "I was going to Spain with a medical unit supported by all shades of decent opinion in Britain. I felt that I had a very heavy responsibility towards its members and towards those who were sending us. We were a small unit and I was not going to do anything behind the backs of its members... I went on to say that a party fraction was being established in the Unit and since I was sure that its members had the work as much to heart as the rest of us it was hard to see why it had seemed necessary to create it." He then went on to complain about the addition of CPGP member, Hugh O'Donnell, to the unit.

Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit later explained: " We were mostly young, we were not yet really battle-hardened, though, by now, we had all had a sufficient experience to know what war really meant. We were certainly ready to carry on, we were convinced that our side in the Spanish Civil war was as right as the other was wrong. Even more determinant to our morale was our profound belief, irrespective of our nationality, that we were fighting for the future of our own homelands ; I then believed (as I do today) that Spain's fight was not just for the values that we in England took for granted, it was against forces that were directly antagonistic to Britain. 1939/45 proved us right but, in 1937, our premature anti-fascism was not always understood."

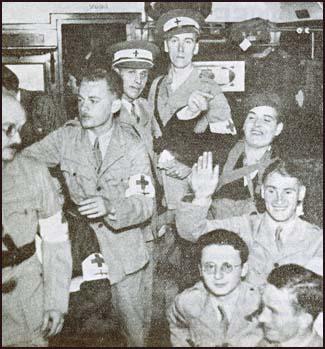

Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit is standing in the middle of the photograph.

On 23rd August 1936 Sinclair-Loutit left for Spain with twenty other volunteers and a fully equipped mobile hospital. On arriving in Barcelona he had a meeting with Luis Companys, the President of Catalunya. His unit included Thora Silverthorne, Peter Spencer (Viscount Churchill) and Stanley Richardson.

According to the woman who later became his second wife: "He found himself heading an autonomous municipal department employing several hundred staff in first-aid posts, a mobile medical unit, rescue parties with light engineering capacity, motorised stretcher parties and a mortuary."

One of his visitors was Edith Bone. "Dr Bone was in her early forties - a wonderful woman, dressed invariably like a Gibson Girl with trim leather belt, light-blue shirt and long dark-blue skirt. She was always hard at work with her Leica and spoke beautiful English with a fine Viennese accent. She went everywhere; she was always alone and seemed to know everybody. I never understood her status or functions."

On 2nd December 1936 Agnes Hodgson wrote in her diary: "I had lunch with Mr Loutit from BMAU. He took me to a Catalan restaurant where we ate well - but much garlic flavoured food. He drank wine, pouring it into his mouth out of a special Spanish vessel - very skilful proceeding. We talked a bit then went for coffee up on a hill, his chauffeur coming with us. Lovely view of hills and harbour. Sun setting - looked at destroyers and foreign sloops outside port - saw a seaplane arriving on the water. Returned to the British Medical Aid Unit's flat to await other colleagues. Had tea and met other members of BMAU down on leave - one played the piano and tuned his violin. Danced a little with Mr Loutit dancing in gum-boots."

Hans Beimler also took a close interest in the activities of Sinclair-Loutit: "Beimler set to with imposing authority and without any preliminary greeting. His words were heavily translated, word-for-word, by a female German comrade who seemed scared of loosing the slightest mite of meaning. She spoke slowly, checking back with him on several occasions. Beimler's voice indicated the shades of his meaning by heavy changes of emphasis and of tone. The interpreter trudged on with monotonous weight."

Kenneth Sinclair Loutit and Thora Silverthorne, a nurse who had been "elected" matron at Granen Hospital that had been set-up to treat wounded members of the Thaelmann Battalion, became lovers and the nurse had a great influence on his political development.

Archie Cochrane, who worked under Sinclair-Loutit, was critical of the way he managed the medical unit: "Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, the official leader of the unit, was a likeable medical student and an obvious secret party member, but I did not think that he would be a good leader. He had a weak streak."

While in Spain Sinclair-Loutit met the journalist Tom Wintringham. When asked what he was up to, Wintringham replied: "Look, the Party as you saw in Paris is the brain, heart and guts of the Popular Front and it's even more so in Spain. Unless the unit is right with the Party you'll be lost." According to Sinclair Loutit, Wintringham was already "formulating the concept of the International Brigades."

At this time Sinclair-Loutit described himself as "a non-party, radical intellectual aged 23, frightened and disgusted by the inhumanity of the depression." Tom Wintringham, who was a leading member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, befriended the young doctor: "He (Wintringham) was helpful and kind in great things and small. To be with a warmly human Marxist who was also a cool soldier made it possible for me possible for me to find the beginning of the path and I count him one of the best friends I ever had."

While in Spain became friends with Alex Tudor-Hart, George Nathan, Cyril Connolly and Julian Bell. Sinclair-Loutit later wrote about Bell: "Though Julian had great worldly experience, he had retained a capacity for wonder, an innocence, a candour, and a ceaseless zest for activity. All this made him magically attractive. Though he detested the heartless destruction of war, it did not make him afraid. He was consistently courageous."

Sinclair-Loutit and Thora Silverthornemarried while on the front-line. The journalist, Sefton Delmer, produced a photo-story for the Daily Express on the marriage. As Sinclair-Loutit recalled in later life: "In accordance with the new secular practice of the Republic, Thora and I had signified our mutual firm commitment, as compañera and compañero. We had done this on the Madrid front and thus were, in then Spanish law and custom, a legal couple which had given Sefton Delmer a little photo-story in the Daily Express."

Like many people who served in the Spanish Civil War, Sinclair-Loutit was appalled by the behavoiur of the CPGB members who followed the orders of Joseph Stalin. He later wrote: "In Spain I gained a profound respect for the soldier and a permanent sense of caution in dealing with intellectual zealots particularly those exercising a function of command. To all of us who were there, Spain proved a nodal experience that influenced us for the rest of our lives. I like to believe that it made me a better person."

On 6th July 1937, the Popular Front government launched a major offensive in an attempt to relieve the threat to Madrid. General Vicente Rojo sent the International Brigades to Brunete, challenging Nationalist control of the western approaches to the capital. The 80,000 Republican soldiers made good early progress but they were brought to a halt when General Francisco Franco brought up his reserves.

Sinclair-Loutit and Thora Silverthorneboth worked at the principal Field Hospital serving the Battle of Brunete. Fighting in hot summer weather, the Internationals suffered heavy losses. Three hundred were captured and they were later found dead with their legs cut off. In retaliation, Valentin González (El Campesino), executed an entire Moroccan battalion of some 400 men. All told, the Republic lost 25,000 men and the Nationalists 17,000. George Nathan, Oliver Law, Harry Dobson and Julian Bell were all killed at the Battle of Brunete.

After the battle Dr. Domanski-Dubois had a long talk with Sinclair-Loutit. "Dubois felt that I must finish my medical studies; he had no use for student martyrs. Also he wanted the Spanish Medical Aid Committee to have a first hand view of Spanish realities. His thesis was that we had both made our contribution to the Brigade and, now that we had helped to make the Medical Service a going concern, we had earned the right to think of our own future."

After returning from the Spanish Civil War he completed his medical degree at St Bartholomew's Hospital. Under pressure from his parents, Sinclair-Loutit, married Thora Silverthorne in a Roman Catholic Church and the couple lived at 12 Great Ormond Street. Their friends during this period included Eleanor Rathbone and Alistair Cooke.

Sinclair-Loutit joined the Holborn branch of the Labour Party. "The Metropolitan Borough of Holborn had always been regarded as a safe Tory enclave in a London which depended, for most of its vital services, on the London County Council with its solid Labour majority... The Holborn Labour Party was a young persons affair; we stumped about Holborn, knocking on doors to find out the felt needs of the people who lived behind them. We had held scores of street corner meetings and I became a competent impromptu speaker. All six of us were returned as Borough Councilors with thumping majorities. We were pledged to get more frequent garbage collections, better Maternal and Child Health Services (including pram shelters for rainy days), a home-work corner in the Public Library for secondary school children, and a number of other practical targets - all of which we delivered fairly quickly."

Sinclair-Loutit joined forces with Stafford Cripps and Aneurin Bevan in the campaign against appeasement. This included speaking on the same platform with members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. In his autobiography, Very Little Luggage, Sinclair-Loutit, explained what happened: "The result was that Cripps, Bevan and myself (midget though I was beside such men) received a letter of anathema from the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party. We were told that we would be expelled from the Labour Party if we continued to appear on platforms that included Communists.... So I found myself sitting in an office in Chancery Lane with Cripps and Bevan while Cripps held up the letter to re-read the National Executive's terms for our rehabilitation. Cripps treated it as though it were a document replete with indecent details in a carnal knowledge case. Bevan said something about preferring to be out than in. The way things were going, so he said, it was no time to be mealy-mouthed. So they refused to assure the National Executive that they would in future keep more right-wing company."

On the outbreak of the Second World War Sinclair-Loutit was appointed Medical Officer in Paris to the Polish Relief Fund. "In October 1939, a Polish Relief Committee had been set up in London, but it was not a good time for public appeals. Chamberlain had frozen the Czech assets held in the City and by some quirk of creative accountancy this money was made available to help the Polish Civilians in France. The first I knew of all this was that one morning I found a message from the Dean of Bart's telling me to go down to some address near Hyde Park Corner. I went down there and within three days found myself at Croydon climbing into an enormous Handley Page biplane. I had been appointed Medical Officer in Paris to the Polish Relief Fund and was to report to the Military Attaché's office in our Embassy."

Sinclair-Loutit returned to St Bartholomew's Hospital as a doctor at the beginning of 1940. "The Dean of Barts then told me of a job in Finsbury, for which my Spanish experience gave me good qualifications, at the then princely salary of six hundred pounds per year." Sinclair-Loutit helped establish Finsbury Health Centre. Angela Sinclair-Loutit, later recalled that it had been "founded on socialist principles that would later become the bedrock of the National Health Service. For the first time, doctors worked side by side with nurses, social workers, radiographers and physiotherapists."

Sinclair-Loutit was also appointed as Medical Officer for Civil Defence in Finsbury. "So, at the age of twenty seven, I found myself in charge of an autonomous municipal department employing several hundred men and women spread out in First Aid Posts (situated in the empty schools), a Mobile Unit, a Depot for the Stretcher Parties with their transport as well as a mortuary. This service worked in cooperation with the Municipal Engineers Light and Heavy Rescue Parties together with a central staff of instructors and supervisors plus local doctors who had volunteered to help. We also had our own garage and repair shop."

He was on duty during the Blitz. On 10th May, 1940 he was involved in trying to extricate survivors from a collapsed block of flats in Stepney. He later told a journalist: "On May 10, the borough was hit so badly it was just a jungle of smoke and flames. I led my rescue team into the wreckage and the first few yards of tunnelling were always the worst; if the building was going to cave in on top of you, it would most likely be at the start. Each bomb that dropped, he said, was a form of Russian roulette in which the trigger is pulled by someone else."

In 1941 Sinclair-Loutit was awarded the MBE for the work that he did during the Blitz. It was presented to him at Buckingham Palace by King George VI, who told him: “It gives me very much pleasure to decorate you. Please tell them in Finsbury how proud I was of London during those times."

Sinclair-Loutit was now transferred to the headquarters of the London Civil Defense Region: "There were in all ninety four separate Local Authorities in the London Civil Defense Region which extended well outside the LCC area and covered a then population of over nine million. I became Secretary to the Standing Committee coordinating these ninety odd Municipalities."

Later that year Sinclair-Loutit met the artist, Janetta Slater, the wife of the Spanish Civil War veteran, Hugh Slater, at a party held by Tom Wintringham. "She had straight hair, little make-up and a very economical and accurate vocabulary. She was beautiful, and she had, in her quietness, an immense presence... From the moment we had met there had been nothing casual about our reaction to each other - it was an immensely specific conviction of our shared sympathy and necessity for each other. The only difference was that she was then alone and I was not."

Eventually, Sinclair-Loutit decide to leave Thora Silverthorne and went to live with Janetta at 2 Dorset Street, just off Baker Street. "I had felt a profound conflict before accepting that the separation from Thora had to come about. It was not willful hedonism that had been the motor for my leaving, nor was I completely carried away; I did indeed know what I was doing. I was reacting to a psychological imperative. Janetta had made me feel a new and different person; the price of this was the abandonment of what had been mine beforehand. It was a big price for a big reward."

Sinclair-Loutit's friends were very critical of his behaviour: "The smallness of mind of people I had held to be friends-for-life surprised me but I had to accept that it is not always easy to stay friends with both parties in a marriage break-up... While I found all this hurtful, I also saw that such partisanship was giving an oblique psychological support to Thora for which I was correspondingly glad."

Sinclair-Loutit still remained married to Thora Silverthorne, who was now a mother of a daughter. Therefore, when Janetta discovered she was pregnant with Nicolette she decided to change her name by deed-poll to Sinclair-Loutit.

Sinclair-Loutit knew George Orwell: "I had always regretted that Orwell never came to our house despite the friendly terms of his relationship with Janetta. My own sporadic meetings with him had never been entirely comfortable; the fact that we had both been in Spain at the same time should have served as a bond but, in our particular case, it was regrettably and un-necessarily divisive. He had fought under the flag of the POUM, as indeed had John Cornford when he first went out. I myself did not feel that we had been on different sides, but Orwell's experiences when the POUM, the independant left, was being broken up at the behest of the Soviet CP, had made him suspicious of those like myself who had been in the International Brigade."

Other friends in London included Cyril Connolly, Stephen Spender, Philip Toynbee and Arthur Koestler. In June 1942, Connolly, the editor of Horizon, published Sinclair-Loutit's article, Prospect for Medicine. Connolly told him: "The bother with you, Kenneth, is that you are too busy doing too many things. To write well, you must care so much that you let all else go."

In his autobiography, Very Little Luggage (2009), Sinclair-Loutit explains that in 1944 he was offered a new post that had become available: "The immediate need was to fill a post in Allied Military Liaison which called for specific language and professional ; there was a clear perspective towards the post-war implantation of UNRRA in the Balkans. To ensure access to military facilities and to situate the work within both British and Allied Military authority the job was listed as for a Lt Colonel on the General Service List... I knew that the decision to leave London and to go to Cairo en route for the Balkans was important but I did not foresee its repercussions over the years. It had been a hard decision to make, even though the spirit of the times - in that spring of 1944 - made assent inevitable to anyone with my own family background."

Janetta Sinclair-Loutit objected strongly to him going abroad. "To her it seemed an incomprehensible, a perverse reversal of priorities, a silly seeking for adventure on my part for which our little family would have to pay the price. She did not want to know any more about it, nor to talk about it. The subject became unmentionable.... Janetta outlawed any talk about the Balkans, about this job or anything to do with my posting. Never before had we had a such a taboo. Months later, without warning, my orders came." Sinclair-Loutit left London on 24th of July 1944.

In Cairo he worked closely with Lord Moyne. He told Sinclair-Loutit: "It's not the last days of war that are going to count. It is the first months of peace that will decide the politics of Europe for the foreseeable future." In his autobiography, Very Little Luggage (2009) he wrote: "In 1944 I was thirty-one years old, and I found myself at the beginning of an international career in a position of leadership to which, at home, I could not possibly have aspired until I was ten or fifteen years older. All this must have gone a bit to my head. In Cairo my ambitions were becoming more and more engaged; Lord Moyne had shown me new perspectives within the nascent United Nations."

Sinclair-Loutit was appointed Director of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in Belgrade. He later recalled: "As the total liberation of the national territory allowed Yugoslavia to take stock of the results of a pitiless total war, we in UNRRA had to measure how to make effective our contribution to the country’s recovery… One of my jobs was to get the Belgrade Faculty of Medicine underway once again... To form an appreciation of epidemic risks, I covered many kilometres over a countryside utterly ravaged by the Nazis."

In the autumn of 1945 Sinclair-Loutit returned to London to collect Janetta and his daughter, Nicolette, to take them back to Yugoslavia. However, Janetta had fallen in love with Robert Kee and refused to leave the country. "The plain fact that my personal life at home had failed as rapidly, and as completely, as my working life overseas had succeeded was something that I had totally failed to anticipate - I had even been thinking that the one would enhance the other."

Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit was recruited in 1950 as the World Health Organisation Medical Adviser to the South East Asia Office of UNICEF in Bangkok. In his unpublished autobiography he remarks: "I felt an immense elation at the prospect of spending the rest of my working life in such company. We were en-grossed with the part our UN Agencies were playing to ensure peace and in re-civilising the world after the traumas of the last decade."

His next posting was as WHO Medical Advisor to the UNICEF office in Paris, responsible for programmes in Africa, Europe and the Middle East. In Eastern Europe, he helped Ministries of Health to set up maternal and child health services.

In 1961, Sinclair-Loutit was asked him to take over the WHO office in Rabat. Over the next eleven years he implemented a wide variety of public health programmes in Morocco. He also served as WHO’s liaison with the new independent government in Algeria.

When he retired from World Health Organisation in 1973 Sinclair-Loutit and his wife Angela continued to live in Morocco. He started up a radio communications and electronic engineering company which carried out many projects in Morocco, including the first mobile radio telephone in the country.

Kenneth Sinclair Loutit died on 31st October 2003.

Primary Sources

(1) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Both of my parents had strong Presbyterian backgrounds. My father's first wife had become a Catholic as an adolescent, when her whole family got caught up in the Gothic Revival. He came back from India to marry her, but the only way to do this expeditiously was to become a Catholic himself. To him, this would have been no more than re-rigging with new canvass, the timbers were solid, and he neither changed the sail-plan, nor even less the course already laid. For thirty years, that first marriage lasted very well until my father chose the wrong time of year to go to Bad Homburg on one of his five-yearly visits. He drank the waters to tidy up his liver when it suited the time-table of the Indian service, not necessarily when it was the Spa season. So that couple drank the waters in the rain while they both caught colds. He knew a sovereign remedy: “walk it off”. They marched around the Taunus until their colds became bronco-pneumonias. My father's first wife died in their hotel room and my half-brother had to come out to collect his mother's coffin and his sick father.

Convalescence in England gave my father time to make some disagreeable discoveries about Austin then his only son. Austin's eyesight had ruled out the Navy but, as he was ingenious and alert, he had been sent on from Downside to read engineering in Cambridge. At Trinity College, he made a name for himself socially by serving dinner backwards to his guests - starting with a liqueur, then coffee and so on in reverse to end up with soup. In the early 1900’s, there had been an undergraduate fashion for putting a miniature photographic portrait on ones visiting cards. Austin had had his taken from behind, claiming that this was his best profile.

Engineering did not really appeal to my half-brother, but he was a good pianist. He avoided the engineering schools, and spent his Cambridge years perfecting his understanding of Chopin while using the remains of his public school Latin and Greek to take an ordinary degree in Classics. With his father away in India Austin would have been able to get away with all this, but soon, with father back and mama dead, there was hell to pay. His father was a man of action. Since there was no question of his son ever becoming a sailor, and since he was not even fit to become an engineer, the sights were lowered. Austin was taken up to Edinburgh, put into the Faculty of Medicine, placed on a frugal allowance, and his father stayed on a few months to institute a proper disciplined regime before returning to India. No sooner had he got to Calcutta, than he was offered an Admiralty job which amounted to sitting with High Court Judges and telling them the difference between port and starboard. This brought my father back to the United Kingdom and gave him the opportunity to make inspections in Edinburgh. Poor Austin became so harried that he quite simply had to get his MD in self-defense.

My then widowed father had two savage bull-terriers. He was walking them in the Edinburgh Park when they started leaping up at a young woman and there was a fearsome cracking of the whip before order could be restored. It seems that the lady took all this in her stride with the end result that my father married her not too long afterwards.

The Catholic Church had previously served my father perfectly well. Consequently, two people both reared as Presbyterians, one aged twenty-three and the other a good forty years older, were married in the Catholic Church. I was to be their only child. The interval between their marriage and my arrival was spent in Florence, my father returning to England whenever the Admiralty or Appeal Courts needed him. By the time the 1914 war arrived, they had settled with their infant son in Cornwall.

(2) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Even as a child of eight I was brought to feel the absence of those who had fallen in the war. They were missed, even on the happiest of our sorties - the picnic fire would not light and someone might say, "Guy would have got it going, he had a magic touch." I could have asked why they had not brought him along and might well have been told that he had gone down in the Dardenelles. The absence of those who had not come back was a reality felt in those early twenties. Those whose wounds had left them handicapped and my own age-mates who were fatherless did not allow us to forget the war. I mention this because it certainly conditioned my own attitude to practical politics later in Cambridge. My age group was short of role-models because we were so short of men of the uncle generation. Uncles do not present the oedipal pitfalls of fathers.

(3) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Father Paul acted as the supervisor of studies of the sixth form as well as being Headmaster. On the 26th of January 1931, he had just finished the routine review of my academic programme when he asked me to sit down again and produced a section from my previous year's diary for the period 12 October to 13 November of 1930. My notes on this interview, taken at the time, record that he held that these pages (which he retained and which had been physically removed from their binding) indicated that I was a dirty minded brute. He told me that on the mere suspicion of recidivism he would immediately expel me. The purloined diary entry to which he objected related to Mark Farrell's panic and confusion when, in his mother's presence, he had clumsily let fall from his pocket a condom obtained in the unfulfilled hope of its employment after a dance in some country house. I pointed out to Father Paul that this entry did not constitute a communication to anyone. By definition diaries were private. I also questioned the right to inspect personal diaries. This was indeed skating on thin ice, as there was the risk of his flying into one of his rages. I did offer as justification that, when adult, "I would be able to see what I was like when I was seventeen", which has turned out to be the case. This interview with Father Paul ended on an indecisive note; perhaps the claim for the privacy of diary entries had been persuasive. I remember it all surprisingly well because, as it was actually taking place, my chronic fear of the man suddenly went, thus the confrontation was easier. When leaving him, I knew that his refusal of all discussion had neutralized my respect both for him and for his office; there had been absolutely no meeting of minds.

The interview about that fragment of diary had been a nasty start for a new term, but I was not playing fast and loose. I realised that I would have to watch my step, but I did not feel in any sort of risk because I had neither sexual guilt nor prospects. I was involved in a number of constructive activities of which the school could only approve. The last Band Parade had been impressive; I had tossed that Drum Major's staff in the air and caught it in my stride, as our Grenadier Drill Sergeant himself said, "like a guardsman." I had believed that with Paul it could at least be live and let live. I hoped that by the year's end, especially if we got the Band prize at the Annual Public Schools' OTC Camp, Father Paul would see me retrospectively in a better light.

My class-mate and friend, Mark Farrell, came from that very special group of British Canadians who had made Montreal the Financial and Cultural capital of Canada. Even in the 1920s this group recognised the importance of the French language. His mother was as British as was her late husband, but she had become adamant about his need to be bilingual long before this had become a generally accepted policy in Canada. So Mark had been sent to Bordeaux to spend the 1931 spring term in total immersion in that language. I had stayed with them in Cheyne Gardens; we had developed a virtually familial mutual understanding so naturally we were keeping in touch throughout Mark's absence in France.

Soon after my tricky interview with Fr Paul, I had received from Bordeaux Mark's report of a very real predicament and of his urgent need for advice. He had certainly been achieving total immersion in French language and culture. Amongst the amenities proper to the prosperous bourgeois milieu of those times must be counted the bordel, to which Mark had been introduced by a member of his host's family. That Mark should have been offered such an outing would in those days have surprised few Frenchman; even a cursory reading of contemporary literature makes this evident. As we all know, maisons tolérées earned their toleration because they were considered to be socially useful. They were seen as a necessary evil which protected the family from the erosion provoked by sentimental intrigues within their own social groupings. Prostitution provided an outlet which the Church in France accepted as the lesser of two evils,

Mark was not being bothered about sociology; he was afraid that he might have caught a disease. This turned out not to have been the case, but when he wrote to me he was very worried. I have a clear memory of the way I addressed his problem and I still believe that I got it right first time. I made two points to Mark. The first point I made was not to feel guilty and to go and see a doctor at once. I said no doctor would despise him or try and make him feel bad about himself. I deliberately tried to boost his morale because he was obviously in desperately low spirits. I had no words of reproof or of moral horror. On reading my letter he would have felt that, had I been in Bordeaux, I would have accompanied him. I had understood that he was desperately upset, almost clinically depressive and that he needed support. He was so full of self-reproach that adding mine would have been in no way helpful. The logic of what I said amounted, in strict theology, to condoning his fault.

Quite apart from dealing with Mark's problem (and partly to take his mind off it) I had given him an account of my last interview with Fr Paul about that purloined entry from diary. As I had lost respect for Father Paul, my description of the interview with him would certainly have been written with the purple pen, nor should anyone ever underestimate the capacity of youth to see through and beyond adult posturing.

I had written this letter on Saturday the 31st of January 1931 and posted it the same day at the little GPO on the main road. It had eight pages according to my diary. Reviewed today, the style of the entries in that diary is pretty callow, touched with would be worldliness and leaning heavily upon whatever I had last been reading. I would have done my best to be mocking and superior and may well have shown some insight into Paul's preoccupations with all the cruel penetration of youthful eyes.

Soon after lunch on Thursday the 5th of February 1931, I was in the library when word was passed to me that the Headmaster wanted to see me. There was nothing remarkable about such a summons. It happened occasionally that he would see a need to discuss some project involving a sixth former. Disciplinary matters he dealt with in the evenings, with the subject being brought along from his dormitory. I walked over to his office wondering whether it was all about the expense of the new side-drums for the OTC Band, or about the planned field visit of the Historical Society of which I was Secretary. I went up the curving Georgian staircase to his floor which overlooked the same wide green view as my own study in the top attics of that same building. Knocking on the door, I went in. He was sitting behind his desk, he did not ask me to sit down. In my mind's eye I can see him still today; I see his pale rather swarthy face and my immediate sensing that something was wrong.

There were no preliminaries:- "You have had fair warning," he said, "you have chosen to ignore it, you persist in writing filth. I cannot keep a rotten apple in the School. You will leave this place in the next hour. Brother Peter will put you on the night train at York and you will be back in the care of your parents’ tomorrow morning. Your accomplice in vice, Mark Farrell, will not be returning to the school, and in the future you yourself may in no circumstances communicate with any member of the school community." This made me loose my footing and I slumped down on the chair beside his desk.

I was completely dumbfounded. I had done absolutely nothing which was remotely vicious or filthy. As I was saying, "But, sir, what have I done?" I saw, from my lower vantage point alongside his desk, the eight page letter to Mark that I had posted outside the school in the GPO box on the main road five days before. The stamped and postmarked envelope lay, open, beside it. He had abusively obtained the letter after it had reached the hands of the Post Office. There was little left to say, not that Paul was seeking any dialogue.

Unfortunately neither the text of my letter, nor that of Mark's, has survived. What became clear that wretched afternoon was that my mail, both in and out, had been under surveillance. This was confirmed later when I learnt from Zwemmers that the history of French literature had been posted to me direct from Paris. It never reached me, so it too, thanks no doubt to its French stamp, had been intercepted. I realised from Paul's manner that this was no bluff, that he would never back down. Anyone at a pre-war Public School had learnt to regard expulsion as a form of capital punishment. In my day, a body of opinion existed that no decent College in Oxford or Cambridge would accept an expulsee. There was no appeal, because there was no way back. I remember saying something about needing time to think and him not understanding that I could not leave a friend in the lurch. His reply still echoes back to me : "If those words were true, you would have brought that vile letter you answered with all this filth," pointing to my letter, "you would have brought it to me and I could have found help for the wretch you call your friend."

(4) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

University undergraduates, themselves then mostly the children of prosperous families were starting to have their consciences troubled by the plight of Hunger-Marchers and of those who, by the Means Test, were forced to sell their possessions before they could obtain the meagre dole payments. It was into this atmosphere that I emerged from the cosy shelter of my Cornish life. Ampleforth had in no way prepared me for this. I did not know what to make of it. Then one or two men in our year failed to return for the next term - their parents could not continue to finance a university education. I had never before been led to question the stability of the society into which I had been born.

America had been hit by the depression in 1930. In the following year the European banking system fell to pieces with the failure in Vienna of the Kredit Anstalt. Britain had a budget deficit, and there was a flight of capital from the City. Parliament was weak; the 289 Labour seats were not enough to give a working majority in the House so the 58 Liberals held the balance of power. Rising unemployment caused misery and alarm, the social and economic symptoms of a major depression had a decisive influence on the General election in the autumn of 1931 which left the Labour Party with only 52 seats. The Liberals were returned in 72 constituencies while the Conservatives won 473. Only 13 of the 558 National Government seats were 'National' Labour. These and the 72 Liberals joining the Government (puppet-led by Ramsay Macdonald) were accused by purists of deserting their liberal or socialist ideals.

The Labour opposition was led by George Lansbury who, as a sincere and devout churchman, did not hesitate to invoke Christian principles in his search for a solution to the problem of poverty. This led to the Tory riposte that "there is nothing in the Bible about a seven-and-a-half hour day." To the rising growth of left wing feeling, the Government replied in a way that failed to satisfy those who were worst hit - notably the unemployed who were soon to number three million. The problems arising from the international economic crisis touched every consumer in the country - some very cruelly. The middle and upper classes became troubled by the social unrest amongst the working-class unemployed, and many were finding it harder and harder to see the working-class reaction as altogether blameworthy. I was becoming aware that the world was subject to forces that hitherto had not been brought to my attention but which I could no longer ignore. I did in fact have one last try at doing so during the coming university long-vacation.

(5) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

The second half of my time in Cambridge was marked first by the Hunger Marchers coming through the town and second by my very nearly dying of septicaemia. I am quite unable to say how it ever came about that the Student Christian Union, the University Socialist Society, and a number of other University groupings - including even the Buchmanites, all united to receive and give hospitality to those Hunger-Marchers on their way from the North to present a petition to Parliament. The Cambridge Town Council had allowed the Guildhall to be converted into a dormitory with an improvised kitchen for a hot meal and a first-aid post.

Helping the Marchers must have been the subject of general consensus as I do not remember any arguments about the involvement of the University community. This Hunger March reception must have been a "popular front" effort though I do not think the term had yet been coined. It was certainly not a sectarian activity of the extreme left and it was indeed a solid success. The Marchers were met on the main road a few miles outside Cambridge. The undergraduate group fell in with them - a Buchmanite Peer, Lord Phillimore, beating the Hunger Marchers own big drum. They had a brass band and, shades of 1914/18, they marched in fours to the tunes many of them had known in France. The column paraded over Magdalene Bridge and on through the Town to the Guildhall. That evening I washed and dressed blistered feet, applying Dr Scholls patches supplied free by a local chiropodist. Local Doctors gave free medical help to the many marchers who were in poor shape. A number were wearing their war-medals, which engendered a sense of remorse amongst those who remembered that the men who returned in 1918 had been promised "a land fit for heroes to live in." Though I did not then realise it, this was my baptism into socio-political activity.

I can still feel the friendly bustling atmosphere inside the Guildhall as we were all setting up the installations. In particular I remember the strapping fresh-faced girl from Newnham who was working at the soup cauldrons and getting vegetables and meat chopped up on a trestle table next to the space reserved for the First Aid Post. I said, rather enviously as she clearly had her job well in hand, that I wished that I knew my job as well as she did hers. I can see that flushed slightly freckled face, with reddish hair pulled back, a most attractive vigourous sight as she looked up to say laughingly, "Well, all I've done in the past is set up plenty of Sunday-school picnics." One does not have to be Cornish to know how much the Labour movement owes to John Wesley.

(6) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

We had been sitting on a café terrace in one of those little Hartz Mountain towns when an officer in SA uniform, greeted us in English and very civilly asked us to join him in another coffee. He turned out to have been an English teacher. He was about the same age as my half-brother, and he too had been through the 1914/18 war. This café acquaintance was my first direct contact with an active member of the Nazi movement . He had good manners, initially showed considerable charm and could have been classed as an intellectual. But he turned to the Nordic unity theme: the Germans and the British were brothers in blood and should be brothers in action. We shared an inherent superiority which gave us both the capacity, and the social duty, to dominate. He expressed relief that the former German colonies were in our good care, and praised the British Empire saying that, were we to march together, the whole world would be at our feet. He was going on about the British Empire as a demonstration of Nordic superiority when I managed to get a word in. My father had often said that it was a misnomer to call the Empire British. It had been brought into being by the Scots, with occasional help from the Irish. In my father's view, so far as the actual work of Empire building was concerned, the English had played but the relatively small part of accepting the tenancy. I played my father's ideas back onto the Sturmbannführer (who had been getting more and more under my skin) asking him first what he thought of the Celts. He said that they had been put in their place by the Anglo-Saxons and that there was no reason to believe that their blood-line, now much diluted, was seriously contaminating. My part in these exchanges cooled the atmosphere, and we had said goodbye without making any arrangements for meeting that evening which had originally been the plan in Mathew's mind.

(7) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Since Truda was not staying in England, I went back with her for an all too short month to Germany. Her family, with its weekly string quartet playing Beethoven to good amateur standards, was a haven, but it was a culture in turned upon itself; it was more than a bit airless. The isolation of this group was sadly understandable as the full force of Nazi social policy was becoming nauseatingly pervasive. One day her father came down to a leaden breakfast wearing in his buttonhole the swastika of the Nazi Professors Organisation. He could no longer avoid joining, since his pension (and his wife's pension should he pre-decease her) would have been forfeit had he persisted in his liberal refusal. For any but the very courageous, it was already too late to resist. The reaction of this good and quiet household was not political - it was motivated by fear. The price of opposition was too often expressed in very brutal terms. As a means of forgetting the hostility of the Nazi world, Truda's family indulged in that specifically German weakness for the transcendental. Rudolf Steiner and anthroposophy became their refuge, and the older members of the family avoided real trouble for the household by giving just sufficient passive consent to the Third Reich. The only place, so Truda told me, where one could still feel sane was on the Island of Sylt. This is a glorified sand-bank with a special ecology and few enough inhabitants for the Nazis to have left it alone. I believe it is quite wrong to view the German spirit as being from its nature conformist or leader-oriented. There is certainly a respect for order, cleanliness and the civic virtues, but, all this being granted, there is a great spirit of philosophical exploration in the German national culture. This has led to Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Bach, as well as Marc and Klee. The Nazis were imposing by force a unity that was utterly foreign both to the good Protestant conscience (and that of Catholics too for that matter) as well as to that vast liberal wave nurtured by the Germany of 1920s. To make everyone act in a clone like unity, to gleichgeschalten, was what the local Nazi party wanted, and they extended this even to the way a girl should dress, to the books she should admire and to the company she kept. For the Raabe family , with the exception of their mediocre failure son Rolfe, this was suffocating, as it was for all their quiet liberal friends in Blankenese.

With uncharacteristic brutality, thinking of her brother, Truda had once said that the Nazi SA (storm-troopers) liked failures - "Their silly uniforms make them feel that they are a success." This turned out to be only too true in Rolfe's case; he did indeed end by joining the SA. Ten years later, at the war's end, I was to get a letter from him in classic terms stating that he had held but a minor position in the Admiralty and consequently he had no guilt for any of the bad things that seemed to have happened behind his back. Rolfe insisted that he had fought a clean war. He had always felt a profound feeling of friendship for England in general and for me in particular. Could I please find him a job in the British Zone? When I went to see Truda in 1947, she told me that Rolfe had been insufferable during the war. He had saved all his possessions from bomb damage by a timely evacuation (using Navy transport) to a Holstein village. His membership of the Nazi movement may have been largely conditioned by self-interest, but he had done little or nothing to help those less well placed than himself. She had not been sorry for him when his removal van was emptied while it traveled after the Armistice by slow train through the Soviet zone to Berlin where he had managed to get himself a job with the Americans.

I had not become an anti-fascist in the 1930s by reading books. I had seen what Fascism was doing to people I liked. It invaded every part of their lives. Neither their work, nor their leisure nor even their home life, had remained untouched. The University vacation lasted a bit more than three months. It was dawning on me in 1935 that an immensely privileged period of my life was ending. My father was getting much older; much of the money we used would die with him on the final settlement of his Trust. I had to buckle down and get qualified quickly. I left Hamburg to start life in London with my German much improved and an informed detestation of fascism. Truda was going to come to London as soon as possible. In the event her return to England was long delayed; we wrote a great deal but it was not until six months later that she was able to get away. Even then she was unable to stay with me as she was accompanied by family friends. An element of imbalance, felt by us both, had crept into our relationship. We had met when she was seventeen which, in 1934, would have been an early age to start a serious love affair. She was a tall, blond, physically active North German. She was very well-read; she looked outward to life with an active hunger for experience of every sort that, when we shared things together, made life a cascade of discoveries. The bother was that the two of us had had so little time for that sharing.

For at least the past year Truda had been refusing invitations to go out alone; she was still a virgin and that was how she wanted it to be until we could get together. But we were seeing each other only at absurdly long intervals. She knew that I was not isolating myself and that I was leading a normal student life. There was no sort of inquisition about girl friends; she knew well that my life was fuller than hers.

(8) The Association of Former WHO Staff (July-September 2005)

At Trinity College, among an extraordinary generation of peers, Kenneth Sinclair Loutit experienced the turbulent political and social events of the time - The Great Depression, Hunger Marches, the rise of Communist and Socialist ideologies and the Nazi Government in Germany. After receiving his degree, he was appointed Administrator of the British Medical Aid Unit for the victims of fascism in the Spanish Civil War, leaving for Spain in August 1936 with twenty other volunteers and a fully equipped mobile hospital. He directed medical operations treating casualties on the front lines of the Spanish Civil War.

(9) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Lord Faringdon (Gavin Henderson, usually called Hendy by his Eton contemporaries) had returned, after a brief marriage which had been without issue, to the bachelordom that suited him better. His own particular version of the Marxist dialectic had enabled him to make a synthesis of Party discipline and the aristocratic vie du chateau. It seems that his butler had become convener of the Party Cell and had the responsibility for the agenda of its meetings, which took place in the library of Buscot Park. Legend had it that the butler would say at the end of dinner: "May I draw to his Lordship's attention that this evening there is a meeting in the Library," but once the meeting started the forms of speech became more appropriate. The butler would ask Comrade Henderson to read the minutes of the last meeting. I am not clear about the membership of this Party Branch; the butler chaired the meetings, and Comrade Henderson was the Branch Secretary. It is hard to believe it was organised on a factory model with a membership drawn from amongst the estate workers and the inside staff of that peer's country house. So far as the Spanish Medical Aid Committee was concerned, I always found Lord Faringdon quick at seizing the nuances of field situations and eminently helpful in solving practical problems.

On his recruitment O'Donnel became more matey; he told me that he was sure that he would be able to be of great help to me personally with the Unit's contacts with local bodies in Spain. I was naturally interested to learn more about his background and how his qualities had been forged and tempered. I was assuming that he had some Spanish language capacity as I'd always seen him around with a British Argentine volunteer who had been rejected on health grounds. In the event it turned out that he spoke nothing but English.

That evening Isobel Brown took me to the CPGB's King Street Headquarters. Harry Pollit, about whom I knew but little and whom I had never seen before, turned out to be a warm friendly man with a manner that made personal contact easy. He had with him someone called Campbell who, in contrast to Pollit, seemed curmudgeonly; I felt he disapproved of me and my accent. Since Pollit's manner encouraged the direct approach, I led off by saying that, as he probably must have heard, I was going to Spain with a medical unit supported by all shades of decent opinion in Britain. I felt that I had a very heavy reponsibility towards its members and towards those who were sending us. We were a small unit and I was not going to do anything behind the backs of its members. They would always know what was happening, and I needed to know that nothing would be going on behind my own back. Pollit commented that this seemed to him an entirely right attitude, but why did I feel the need to express it to him? An old hand, like Pollit, would not have returned the ball to an apprentice player like me unless he had wanted the rally to continue. Thus encouraged I went on to say that a party fraction was being established in the Unit and since I was sure that its members had the work as much to heart as the rest of us it was hard to see why it had seemed necessary to create it. I had nothing to hide and nor conceivably could they. I was ready to demonstrate this by making my administration entirely open. With one exception, everyone in the unit had either been pre-selected or approved, by me. Pollit asked who the exception was, and when I said O'Donnel, he let out a laugh in which Cambell did not join. As I did not seem to be getting very far I then played my only other card saying, "If you won't let them come out into the open let me come inside. Let me join you, as we can't have a Unit being pulled two ways". This did indeed provoke Cambell who was emphatic saying that the Party was not a darts club a man can just walk into at will when it suited him. To which I remarked that this was exactly what I felt about the Unit. Pollit seemed to be enjoying himself and came back with a friendly bit about the lad having a point. He went on to say that the Unit was a real Popular Front activity. He asked Campbell to get that well across to O'Donnel and, turning to me he said something like, "The world's very far from perfect. You'll have to take the rough with the smooth out there". Turning to Cambell he said, "I am going to give him something to show that, in the spirit of today, we trust him." To me he added, "Keep it in a safe place like inside your belt. Only use it if you really need to. The party will always back that Medical Unit; you've helped a lot by coming to see us". He went to his desk and typed a few lines, reciting them as he did so, requesting that I should be given every help. He signed it and put a rubber stamp on it. Then, to my surprise, he cut the document down to minimum size with a pair of scissors. When he put in my hands I realised that it was not typed on paper but on a piece of white silk.

That evening Mary Redfern Davies very neatly opened the seam of a leather belt and slipped in the little bit of silk. Until typing these words in 1995, the only people outside Pollit's office to know of the existence of that scrap of silk have been myself, Mary Redfern Davies and Thora Silverthorn. It is just possible that when O'Donnel was told to behave himself, he was also told that I was carrying a word from Harry Pollit. I was to have reason to consider this a year later.

So on the 23rd of August 1936 a friendly group of relative strangers, dressed in khaki drill from Millet's Army Surplus stores, arrived at Victoria Station. Our destination was Barcelona. For me it was a completely overwhelming occasion; I was dropping with physical fatigue. Seeing us off, we were faced with a galaxy of Mayors in their robes and chains, Trade Union Banners, the leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party Arthur Greenwood, and 10,000 others - all on parade. It was an immensely impressive experience for the staff of that First British Medical Unit. Our little group had not realised before that what we were doing was considered so important. Such a send-off provoked in us all the beginnings of our sense of collective responsibility. One thing that sticks out in my mind about that journey was the solicitude the railway men showed to us everywhere, in England as in France.

I did eventually learn something of O'Donnel's unusual job-history. He had been jailed for incitement to mutiny after distributing leaflets to airmen; his case had been aggravated by his display of a disloyal banner at the annual Hendon Air Force Show. He had built a certain reputation for 'agitprop', and, at the peak of his career, had enlivened the Jubilee carriage drives of Queen Mary and King George V to the Metropolitan Borough Town Halls. On these State occasions the Sovereign's route had always been decorated with flags and banderoles bearing loyal messages such as "GOD BLESS OUR KING AND QUEEN". Hugh O'Donnel had devised ways by which, at the pull of a string, the banderole would unwind to read "TWENTY FIVE YEARS OF HUNGER AND WAR". I learnt that this did not in any way upset the King. My authority lies in a statement made by the His Majesty himself which had inadvertently been broadcast by the BBC when a mike had been left alive at the end of the Royal visit to Stepney. King George the Fifth had always liked a bet; leaving the Town Hall the Sovereign said to the Queen, "I'll lay you two to one in half crowns there will be more than three on the way back," to which his Consort, who also liked a bet, had replied: "Taken."

I did not see much application in Spain for Hugh O'Donnel's talents, but it was clear that I was stuck with him. Once or twice I had noticed him to be the centre of a small group which changed the subject of conversation when I joined them. I did not fancy the risk of becoming subject to a concealed veto under his inspiration via a CP linkage, so I decided to go to the top. I had really come to like and to respect Isobel Brown (an open Communist who was the Secretary of the Committee for the Relief of the Victims of Fascism), so I told this approachable lady that before we left for Spain I wanted to meet Harry Pollit, the Secretary General of the CPGB. Isobel Brown replied that Pollit did not see anybody any day just like that, and I retorted in a rather flip way that neither did I go off to Spain any day, anyhow, just like that.

(10) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

We the volunteer crew of that Spanish Medical Aid Unit, were far from being an homogenous group; none of us had ever worked together beforehand; we lacked a common culture and in fact were a very mixed lot. As this diversity leaps into my mind's eye it still strikes me as an asset. In our very different ways we each had our own unique contribution. I wish I could write about them all.

Nurse Bird must have been about forty years old in 1936. She had been in an ambulance unit in the Great War when she must have been a pretty blond kid. Naturally, she wanted to use her previous experience, and it was she who went up to the Front with the stand-by ambulance. She gave to us all an example of quiet courage. I still think of her as exemplary and picture her, a bit weather beaten without make-up but somehow young, leaning against the Bedford's radiator, sharing a fag with one of our two Cockney drivers - both Charlies. At first we found her tough-guy stance touchingly engaging; it grew more pronounced when she acquired a pair of breeches and spoke with her cigarette in her mouth. Then she got a pistol in her belt which I had to ask her to return to its donor (the Geneva Convention etc said "no") but in the end we realised that her 1914-18 nostalgia had deeper roots. Her hair shortened into a butch cut and she moved into a sheltering recess in the dormitory with Lisl, a German volunter nurse from Barcelona. Harry Forster was a magnificent improviser; he doubled as steriliser, electrician, plumber and quarter-master. He had a genius for brewing-up tea at the right moment. He kept our two Charlies from creating too much hell; they were a couple of lorry drivers who had come out mostly for a lark. They were interested in girls, but picking up female company in Grañen needed another technique than theirs. They resented attempts to discipline them but their hearts were certainly in the right place and they never let us down when the Front was active.

Thora Silverthorne, our Operating Theatre Chief Nurse, had been born into a large mining family in Abertillery. She was about my age. In the 1920s her father had been an early recruit to the Communist Party and had been active in that now vanished culture of the Welsh valleys. He had had a fine singing voice; his interests went much wider then politics. Thora had been bright at school and had been selected by her father's Union Lodge to be sent to Moscow with a scholarship to the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute. She decided for herself that she wanted to be a nurse so she went instead to the Radcliffe Infirmary at Oxford. She had been steeped in three cultures: native Welsh Radical practice and thought, modern Medicine and, thirdly, that general awareness with its self-confident boldness, its refusal of unthinking convention, that in those days was the main result of residence in Oxford or Cambridge. She could just as well have ended up gracing a Master's Lodge as behind the Secretary General's desk of a major Trade Union. She would never have been a success as an apparatchik.

It was of course inevitable that I should fall in love with Thora; all-in-all we behaved responsibly. We were only a few kilometres from an active war front. Our daily work told us that bullets kill, when there are plenty around it alters the perspectives of emotional life. We both worked extremely hard, without leisure for any sweet dalliance. Thora. was outstandingly competent. Her social ease and her care for her neighbour put her above fault. She had a clear bright eye with a wonderful freshness of attention, plus a quality of instinctive understanding of other peoples feelings, which made her social relationships successful. All this encased in Celtic good-looks made me a very privileged man. In a corresponding measure, our quite unconcealed relationship provoked more sympathy than criticism. The fact that the Unit had been successfully implanted, that it served a real function, and had not been the subject of political, medical or military catastrophe, was due to the quality of the collective work of the twenty or thirty, mostly young, people concerned. This had to be orchestrated by the Administrator. He was criticised, but no one else showed any ambition to replace him. Such toleration owed much to the fact that I had understood early in my life that orders will not be followed unless the person who gives them is capable of carrying them out himself. I therefore took an active part in all the fatigues and jobs incidental to setting up and running the hospital. Another factor was the very sense of commitment which had provoked our staff to volunteer in the first place. The inspiration behind this had varied sources; there were some quiet Quakers; there were some sons and daughters from the solid old democratic working class that, in those days, gave weight to the Trade Union and Cooperative movements.

There were also the communists, numerically not a major element, some of whom were inspirational and here I think of Aileen Palmer. Aileen was the child of Nettie (Janet Higgens) and Vance Palmer of the Melbourne Independant Theatre which put them both into the Australian literary pantheon. She had an acute sense of duty and put her whole being into her work. She had no special skills, but she would turn her hand to anything, using any spare moment to act as secretary and record keeper. In action, she kept the register of admissions and of discharges - whether these latter were by evacuation to the rear or by exitus lethalis, by death.

Aileen therefore became the custodian of the effectuos de los muertes those pathetic little bundles of treasured objects that were all that remained of the material and emotional existence of a once living lively man. When there was any trace of his origins, Aileen wrote a letter to his family but mostly there was a name without an address, a cigarette lighter and some photos all wrapped in a handkerchief or in a pouch together with a knife. The thought of these poor treasures, piled on the shelf behind Aileen's desk, still tugs at my heart as does the knife lying on my desk that she gave me from that sad and modest store. From this same source we also re-equipped those discharged casualties who would otherwise have left our hospital with nothing they could call their own. Aileen was indeed of the stuff of the Saints - but there was nothing transcendental in her make-up; she was a marxist but not a party fanatic. Preaching did not interest her, action did. Had Aileen been born a few hundred years earlier, she would been a Franciscan or a Carmelite. Coming to Spain in 1936 had enabled her vocation to flourish and her devotion to be expressed in the "apostolate of works", as her predecessors would have called it. She was so convinced that she was ugly that she punished her femininity by neglecting her appearance; Thora would tease and chivvy her into taking minimum care of herself and of her looks. Aileen, whose only indulgence was in continuous cigarette smoking, showed a very sweet protectiveness towards Thora and myself. She loved seeing Thora happy and this made her tolerant about us.

(11) Agnes Hodgson, diary entry (2nd December, 1936)

Much waiting here in Spain because they are all so busy. I had lunch with Mr Loutit from BMAU. He took me to a Catalan restaurant where we ate well - but much garlic flavoured food. He drank wine, pouring it into his mouth out of a special Spanish vessel - very skilful proceeding. We talked a bit then went for coffee up on a hill, his chauffeur coming with us. Lovely view of hills and harbour. Sun setting - looked at destroyers and foreign sloops outside port - saw a seaplane arriving on the water. Returned to the British Medical Aid Unit's flat to await other colleagues. Had tea and met other members of BMAU down on leave - one played the piano and tuned his violin. Danced a little with Mr Loutit dancing in gum-boots. I was very tired. John Fisher, an Australian journalist, arrived to find out our whereabouts and Lowson arrived shortly afterwards. We went to the Hotel Espana where the Government have billeted us. Had a glorious bath. Mr O'Donnell introduced three British engineers of the party who are working here.

The others did not want to eat again but as I did John Fisher asked me to dine with him at his Hotel Nouvel. Went for coffee to the Ramblas Cafe and met several journalists and interpreters. Stayed talking and waiting while John Fisher made enquiries, and so to bed.

(12) Leah Manning, A Life for Education (1970)

Whilst I had been absent from London, the Committee, with which I was to be most closely associated during the Spanish war, had been formed. Isabel Brown, a dedicated communist, had been receiving sums of money from all over the country to be used for Spanish relief. Medical aid was urgently needed doctors, nurses, trucks and their drivers, and supplies of all kinds. Isabel set about finding people willing to sit on an all-party committee who would undertake the task of raising funds, interviewing personnel, and sending all these things and people to Spain. She brought together the Spanish Medical Aid Committee. We had three doctors on the committee, one representing the T.U.C., and I became its honorary secretary. The initial work of arranging meetings and raising funds was easy. It was quite common to raise £1,000 at a meeting, besides plates full of rings, bracelets, brooches, watches and jewellery of all kinds. Isabel and I had a technique for taking collections which was most effective, and, although I was never so effective as Isabel (I was too emotional and likely to burst into tears at a moment's notice), I improved. In the end, either of us could calculate at a glance how much a meeting was worth in hard cash.

The work soon became so onerous that my job as honorary secretary was relieved by the appointment of George Jeger as salaried secretary. His work through the next three years kept S.M.A.C. running on oiled wheels. I don't think we ever had a moment's anxiety-supplies, instruments, drugs, vehicles, above all doctors, nurses and drivers, had to be found. All personnel going to Spain had to be interviewed and vetted by the committee; the first medical unit was sent out under Sinclair Loutit. I don't think we made many mistakes, but driving up to the front with medical supplies was dangerous work and several of our drivers were wounded. We suffered a severe loss in the death of George Green who was in charge of all our convoys. No one was to blame for this : we were finding our way in unknown territory. But we couldn't go on risking valuable lives, or ambulances and trucks full of supplies, trying to find hospitals or the front in a chaotic situation and with scarcely anyone speaking the language. It was all too amateurish and haphazard. We needed a focal point and someone resident in Spain to whom all supplies should be sent and all personnel report for posting.

(13) Archie Cochrane, One Man's Medicine (1989)

The males were worse than the females. Lord Peter Churchill was a good public relations figure, a fair administrator, and a friendly person; but I was worried that his fairly obvious homosexuality or bisexuality might run the unit into legal trouble, although I knew little of the laws in Spain. Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, the official leader of the unit, was a likeable medical student and an obvious secret party member, but I did not think that he would be a good leader. He had a weak streak. O'Donnell, the chief administrator, who had made the bad speech in Paris, was even worse when I met him. I thought him stupid, conceited, and erratic. I certainly did not like the idea of his being in charge. The quartermaster, Emmanuel Julius, also seemed second rate and rather schizoid. The only surgeon, Dr. A. A. Khan, who was studying in the UK for the FRCS, was reserved, non-political, and rather worried. Of the other two male doctors, one was an American, Sollenberger, and the other, Martin, a former member of the Royal Army Medical Corps. I took a poor view of them both. In addition there were two other medical students.

(14) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

We were mostly young, we were not yet really battle-hardened, though, by now, we had all had a sufficient experience to know what war really meant. We were certainly ready to carry on, we were convinced that our side in the Spanish Civil war was as right as the other was wrong. Even more determinant to our morale was our profound belief, irrespective of our nationality, that we were fighting for the future of our own homelands ; I then believed (as I do today) that Spain's fight was not just for the values that we in England took for granted, it was against forces that were directly antagonistic to Britain. 1939/45 proved us right but, in 1937, our premature anti-fascism was not always understood. I had not yet perceived the nature of Stalinism, my levels of contact were not with very senior levels.

(15) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Thora and I had both felt perfectly happy and settled as we were, but our lack of British formal status troubled my mother and Austin my half-brother more than it did my father. I had always been very close to my half-brother so he acted as intermediary. He put it to me that, considerations of religion apart, it was unfair to my parents to deprive them of the comfort of seeing me settled down.