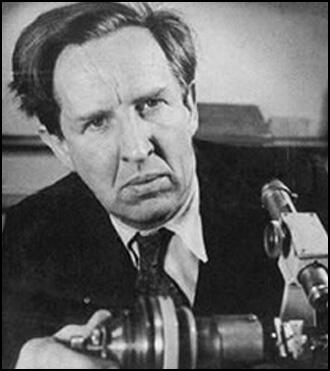

J. D. Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (always known as J. D. Bernal) was born in Nenagh, Ireland, on 10th May 1901. He was educated at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire and Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

In 1923 Bernal joined the Communist Party. Greatly influenced by the work of John Haldane, the two men joined Julian Huxley, John Cockcroft and sixteen other British scientists on a visit to the Soviet Union in 1931. While there they had meetings with Nickolai Bukharin and other government leaders.

Bernel's research helped developed modern crystallography and he was a founder of molecular biology. He eventually became professor of physics at Cambridge University and in 1932 worked on the development of X-ray crystallography with Dorothy Hodgkin. Over the next four years Hodgkin and Bernal produced 12 joint crystallographic papers. Bernal left the Communist Party in 1934 but he continued to be active in left-wing politics.

In 1937 Bernal became professor of crystallography at Birkbeck College. Bernal wrote several books on Marxism and science. This included the Social Function of Science (1939) and Marx and Science (1952).

During the Second World War Bernal was scientific adviser to Lord Mountbatten. He carried out several research projects for the government. This included working with Solly Zuckerman on the impact of bombing on people and buildings.

Tom Hopkinson met Bernel during this period: "J. D. Bernal, a professor at Birkbeck College known to his friends as Sage, partly because of his vast fund of knowledge and partly on account of his enormous head with its shock of wavy hair. Sage had now teamed up with another still more celebrated young professor, Solly Zuckerman, best known at that time for his studies of apes. During the course of the war they would together undertake a whole series of important assignments, but at this moment they were looking into the precise effects of bombing both on people and on buildings, into which it seemed very little research had previously been carried out. Their immediate concern was a casualty survey for which they would travel up and down the country to wherever some incident appeared to demand investigation, and I listened fascinated while they told me what they were doing."

Herbert Butterfield argued: "Bernal was a big man of captivating charm who certainly influenced hundreds of undergraduates. He was that rare creature, a person of truly seminal ideas on a host of subjects, yet one who would never have exercised the cumulative persistence with detail required to win a Nobel Prize. I liked Bernal enormously."

and Dina Fankuchen in September, 1939.

In August 1943 he attended the Quebec Conference and helped to select the landing beachers for the D-Day invasion of France. In the 1940s Bernal began living with Margot Heinemann and gave birth to a daughter, Jane Bernal.

In 1947 Bernal was awarded the US Medal of Freedom. However, his left-wing views made him an unwanted guest during McCarthyism and the US government refused to let him have an American visa. Bernal became vice-president of the World Peace Committee and in 1951 founded Scientists for Peace, the forerunner of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND)..

Along with Rosalind Franklin Bernel carried out research into the tobacco mosaic virus (1953-58). Bernal continued to publish books and this included The Origin of Life (1967).

J. D. Bernal died on 15th September 1971.

Primary Sources

(1) Herbert Butterfield, interviwed by Andrew Boyle for his book The Climate of Treason (1979)

Bernal was a big man of captivating charm who certainly influenced hundreds of undergraduates. He was that rare creature, a person of truly seminal ideas on a host of subjects, yet one who would never have exercised the cumulative persistence with detail required to win a Nobel Prize. I liked Bernal enormously.

(2) Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time (1982)

During this winter (1940) I met again someone I had come across a few years earlier at Chelsea parties. This was J. D. Bernal, a professor at Birkbeck College known to his friends as Sage, partly because of his vast fund of knowledge and partly on account of his enormous head with its shock of wavy hair. Sage had now teamed up with another still more celebrated young professor, Solly Zuckerman, best known at that time for his studies of apes. During the course of the war they would together undertake a whole series of important assignments, but at this moment they were looking into the precise effects of bombing both on people and on buildings, into which it seemed very little research had previously been carried out. Their immediate concern was a casualty survey for which they would travel up and down the country to wherever some incident appeared to demand investigation, and I listened fascinated while they told me what they were doing.

"Well," I said, "now you've found all this out, suppose you give me some simple precautions for getting around safely over the next few years?"

"We could, of course," Sage answered. "But it's a waste of time since you certainly won't act on them."

I objected that his attitude was unscientific; how could he know without putting the matter to the test?

"Very well," he said, "we'll see. If bombs are falling, lie face downwards in the gutter. Gutters give good protection - blast and splinters will almost certainly fly over you. But in case you do get injured, always wear a notice round your neck. Something conspicuous - about the size of a school exercise book."

"Why do I need that?"

"The effect of blast is to pressurize the lungs - equivalent to suddenly giving you pneumonia,' he explained. 'So if a Heavy Rescue man or a sixteen-stone air raid warden kneels on your chest to administer artificial respiration, you've had it! Your notice will say "Weak Chest. Don't touch," or words to that effect. You're a journalist- you can think up your own form of words."

"Thanks," I said. "But if I'm lying in the gutter with my notice, I can't be moving around."

"Oh, if you want to move around - that's easy! All you need to do is wrap an eiderdown tightly round you. It absorbs the

blast and protects your lungs. But of course it won't be much help against splinters."

(3) Rosalind Franklin, letter to Anne and David Sayre (17th December 1953)

For myself, Birkbeck is an improvement on King's, as it couldn't fail to be. But the disadvantages of Bernal's group are obvious - a lot of narrow-mindedness, and obstruction directed especially at those who are not Party members. It's been very slow starting up there, but I still think it might work out all right in the end. I'm starting X-ray work on viruses (the old TMV to begin with) and I'm also to have somebody paid by the Coal Board to work under me on coal problems more or less the continuation of what I was doing in paris. But so far I've failed to find a suitable person for the job.