The Daily Mail : 1896-1940

The journalist Alfred Harmsworth decided to start a newspaper based on the style of newspapers published in the USA. His younger brother, Harold Harmsworth, an accountant, arranged for the raising of the money for the venture. By the time the first issue of the Daily Mail appeared for the first time on 4th May, 1896, over 65 dummy runs had taken place, at a cost of £40,000. When published for the first time, the eight page newspaper cost only halfpenny. Slogans used to sell the newspaper included "A Penny Newspaper for One Halfpenny", "The Busy Man's Daily Newspaper" and "All the News in the Smallest Space". (1)

Harmsworth made use of the latest technology. This included mechanical typesetting on a linotype machine. He also purchased three rotary printing machines. In the first edition Harmsworth explained how he could use these machines to produce the cheapest newspaper on the market: "Our type is set by machinery, and we can produce many thousands of papers per hour cut, folded and if necessary with the pages pasted together. It is the use of these new inventions on a scale unprecedented in any English newspaper office that enables the Daily Mail to effect a saving of from 30 to 50 per cent and be sold for half the price of its contemporaries. That is the whole explanation of what would otherwise appear a mystery." (2) It was later claimed that these machines could produce 200,000 copies of the newspaper per hour. (3)

The Daily Mail was the first newspaper in Britain that catered for a new reading public that needed something simpler, shorter and more readable than those that had previously been available. One new innovation was the banner headline that went right across the page. Considerable space was given to sport and human interest stories. It was also the first newspaper to include a woman's section that dealt with issues such as fashions and cookery. Most importantly, all its news stories and articles were short. The first day it sold 397,215 copies, more than had ever been sold by any newspaper in one day before. (4)

Harmsworth gained many of his ideas from America. He had been especially impressed by Joseph Pulitzer, the owner of the New York World. He also concentrated on human-interest stories, scandal and sensational material. However, Pulitzer also promised to use the paper to expose corruption: "We will always fight for progress and reform, never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fight demagogues of all parties, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare, never be satisfied with merely printing news, always be drastically independent, never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty." (5)

In order to do this Pulitzer pioneered the idea of investigative reporting that eventually became known as muckraking. As Harold Evans, the author of The American Century: People, Power and Politics (1998) has pointed out: "Crooks in City Hall. Opium in children's cough syrup. Rats in the meat packing factory. Cruelty to child workers... Scandal followed scandal in the early 1900s as a new breed of writers investigated the evils of laissez-faire America... The muckrakers were the heart of Progressivism, that shifting coalition of sentiment striving to make the American dream come true in the machine age. Their articles, with facts borne out by subsequent commissions, were read passionately in new national mass-circulation magazines by millions of the fast-growing aspiring white-collar middle class." (6)

Alfred Harmsworth completely rejected this approach to journalism. "Looking back, what it (the Daily Mail) lacked most noticeably was a social conscience... Alfred had no desire to start looking for social evils, and no need. What he had to keep in mind were the tastes of a new public that was becoming better educated and more prosperous, that wanted its rosebushes and tobacco and silk corsets and tasty dishes, that liked to wave a flag for the Queen and see foreigners slip on a banana skin." (7)

One of his journalists, Tom Clarke, claimed that his newspaper was for people who were not as intelligent as they thought they were: "Was one of the secrets of the Daily Mail success its play on the snobbishness of all of us? - all of us except the very rich and the very poor, to whom snobbishness is not important; for the rich have nothing to gain by it, and the poor have nothing to lose." (8)

Harmsworth made full use of the latest developments in communications. Overseas news-gathering offices opened in New York and Paris were aided by advances in cable transmission speed at the General Post Office, which had reached 600 words per minute by 1896. He also exploited the expanding British railway system to distribute the newspaper to the home market so that people all over Britain could read the newspaper over their breakfasts. It has been claimed that the Daily Mail was the first truly national newspaper. (9)

The Daily Mail and the Conservative Party

Alfred Harmsworth made it clear to the leaders of the Conservative Party that the newspaper would provide loyal support against the movement towards social change. Arthur Balfour, the leader of the party in the House of Commons, sent a private letter to Harmsworth. "Though it is impossible for me, for obvious reasons, to appear among the list of those who publish congratulatory comments in the columns of the Daily Mail perhaps you will allow me privately to express my appreciation of your new undertaking. That, if it succeeds, it will greatly conduce to the wide dissemination of sound political principles, I feel assured; and I cannot doubt, that it will succeed, knowing the skill, the energy, the resource, with which it is conducted. You have taken the lead in the newspaper enterprise, and both you and the Party are to be heartily congratulated." (10)

In July 1896, Harmsworth asked a friend, Lady Bulkley, to write to Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, the new prime minister, suggesting that in return for supporting the Conservative Party, he should be rewarded with a baronetcy. The letter pointed out that as well as owning several pro-conservative newspapers he had recently established "the Daily Mail... at a cost of near £100,000". Salisbury refused but was willing to offer a knighthood instead. Harmsworth rejected the offer and commented that he was willing to wait for a baronetcy. (11)

Alfred Harmsworth was a passionate supporter of the British Empire and he is said to have idolised two men, Joseph Camberlain and Cecil Rhodes. He intended to use his newspaper and the rest of his publications to "strum the Imperial harp". According to Harry J. Greenwall, the author of Northcliffe: Napoleon of Fleet Street (1957) Harmsworth "with the Daily Mail unleashed a tremendous force of potential mass thought-control" as it became the "trumpet... of British Imperialism." (12)

George W. Steevens was one of those who heard Harmsworth speak on the subject of Rhodes: "I met last night perhaps the most remarkable man I have ever seen... It is Harmsworth... He is very young and his speech showed that he rates Rhodes too high. Rhodes is as strong as Bismarck, and youth rates strength too high, but Rhodes was never sharp and has become stupid. Harmsworth himself is superior, in that he is probably both strong and sharp." (13)

On the sixtieth anniversary of Queen Victoria coming to the throne Alfred Harmsworth wrote: "We ought to be a proud nation today. Proud of our fathers that founded this Empire, proud of ourselves who have... increased it, proud of our sons, who we can trust to keep what we had... and increase it for their sons in turn and their son's sons. Until we saw it (the great pageant) all passing through our city we never quite realised what Europe meant... It makes life newly worth living... better and more strenuously to feel that one is a part of this enormous, this wonderful machine, the greatest organisation the world ever saw." (14)

For the first three years Alfred Harmsworth edited the Daily Mail with the help of S. J. Pryor, who he appointed as managing director. On the outbreak of the Boer War in 1899 he sent Pryor to organize the war coverage. While he was away Harmsworth gave the managing director job to Marlowe. "It was now unclear which of them was in charge, so they would race each other every morning to get to the editor's chair first and stay there, with Northcliffe looking on and enjoying the joke. Marlowe emerged victorious: it is said he got up earlier and had the foresight to bring sandwiches for his lunch; maybe he also had the stronger bladder." (15)

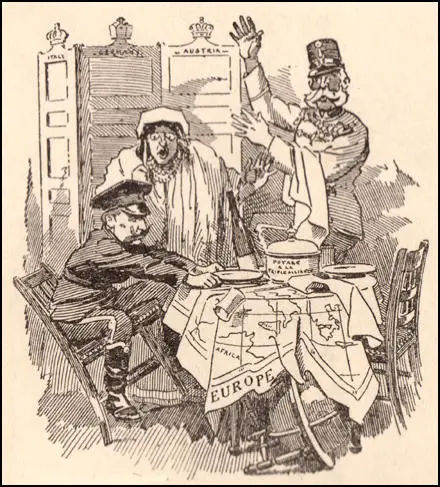

Alfred Harmsworth became very concerned about the dangers posed by Germany. He sent his leading journalist, George W. Steevens, to report on the country: "The German army is the most perfectly adapted, perfectly running machine. Never can there have been a more signal triumph of organization over complexity... The German army is the finest thing thing of its kind in the world; it is the finest thing in Germany of any kind... In the German army the men are ready, and the planes, the railway-carriages, the gas for the war-balloons, and the nails for the horseshoes are all ready too... Nothing overlooked, nothing neglected, everything practised, everything welded together, and yet everything alive and fighting... And what should we ever do if 100,000 of this kind of army got loose in England?" (16)

Harmsworth became convinced that Britain would have to go to war with Germany and urged the government to increase its spending on defence: "This is our hour of preparation, tomorrow may be the day of world conflict... Germany will go slowly and surely; she is not in a hurry: her preparations are quietly and systematically made; it is no part of her object to cause general alarm which might be fatal to her designs." (17)

In an interview Harmsworth gave to a French newspaper he explained his views on Germany: "Yes, we detest the Germans, we detest them cordially and the make themselves detested by all of Europe. I will not permit the least thing that might injure France to appear in my paper, but I should not like for anything to appear in it that might be agreeable to Germany." (18)

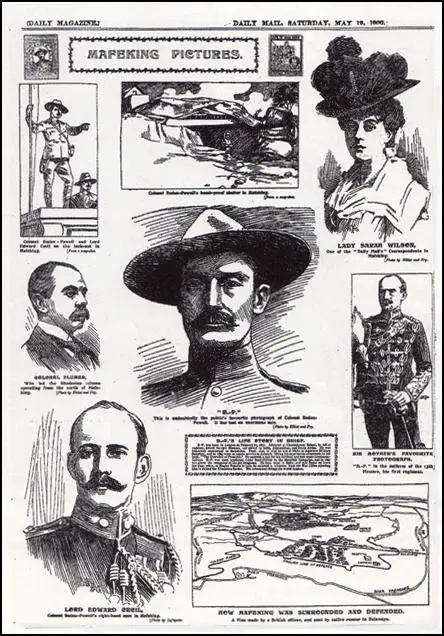

The Boer War

The Boers (Dutch settlers in South Africa), under the leadership of Paul Kruger, resented the colonial policy of Joseph Chamberlain and Alfred Milner which they feared would deprive the Transvaal of its independence. After receiving military equipment from Germany, the Boers had a series of successes on the borders of Cape Colony and Natal between October 1899 and January 1900. Although the Boers only had 88,000 soldiers, led by the outstanding soldiers such as Louis Botha, and Jan Smuts, the Boers were able to successfully besiege the British garrisons at Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley. On the outbreak of the Boer War, the conservative government announced a national emergency and sent in extra troops. (19)

On 25th July, 1900, a motion on the Boer War, caused a three way split in the Liberal Party. A total of 40 "Liberal Imperialists" that included H. H. Asquith, Edward Grey, Richard Haldane and Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, supported the government's policy in South Africa. Henry Campbell-Bannerman and 34 others abstained, whereas 31 Liberals, led by David Lloyd George, voted against the motion.

Alfred Harmsworth, a strong supporter of the war, saw this as an opportunity to damage the Liberal Party. A series of articles appeared in the Daily Mail that questioned the patriotism of people like David Lloyd George. The old-fashioned "Little Englander" position, said the newspaper, by sympathizing with the enemy in the South African crisis, had failed to interpret the sentiment of the nation for "England and Empire". According to Harmsworth, for the Liberal Party to survive, its only hope was to regain the trust of the country by supporting the band of thirty or so Liberal Imperialists, led by Rosebery, Asquith and Grey." (20)

Robert Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury, decided to take advantage of the divided Liberal Party and on 25th September 1900, he dissolved Parliament and called a general election. Lloyd George, admitted in one speech he was in a minority but it was his duty as a member of the House of Commons to give his constituents honest advice. He went on to make an attack on Tory jingoism. "The man who tries to make the flag an object of a single party is a greater traitor to that flag than the man who fires upon it." (21)

The Daily Mail supported both the Conservatives and the Liberal Unionists in the election. Harmsworth had developed a close relationship with Winston Churchill, who was attempting to capture Oldham for the imperial cause. Churchill proclaimed the opponents of the government the enemies of Britain and the Empire. He claimed on one poster: "Be it known that every vote given to the radicals means two pats on the back for Kruger and two smacks in the face for our country". (22)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman with a difficult task of holding together the strongly divided Liberal Party and they were badly defeated in the 1900 General Election. The Conservative Party won 402 seats against the 183 achieved by Liberal Party. However, anti-war MPs did better than those who defended the war. David Lloyd George increased the size of his majority in Caernarvon Borough. Other anti-war MPs such as Henry Labouchere and John Burns both increased their majorities.

The Boer War proved to be very popular with the British public. In 1898 the Daily Mail was selling 400,000 copies a day. Harmsworth encouraged people to buy the newspaper for nationalistic reasons making it clear to his readers that his newspaper stood "for the power, the supremacy and the greatness of the British Empire". By 1899 it had reached 600,000 and during the most dramatic moments of the war in 1900 it was almost a million and a half. (23) According to Adrian Addison, Harmsworth knew his readers would enjoy a good war. He would often say: "The British people relish a good hero and a good hate." (24)

Alfred Harmsworth had a patronising and sententious attitude towards women: "Nine women out of ten would rather read about an evening dress costing a great deal of money - the sort of dress they will never in their lives have a chance of wearing, than about a simple frock such as they could afford. A recipe for a dish requiring a pint of cream, a dozen eggs, and the breasts of three chickens pleases them better than being told how to make Irish stew." (25)

1905 Aliens Act

The unpopularity of the Jewish community in the 19th century can be traced back to an event that took place in Russia. On 13th March, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by the People's Will group. One of those convicted of the attack was a young Jewish woman, Gesia Gelfman. Along with Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, and Timofei Mikhailov, Gelfman was sentenced to death. (26)

The People's Will contacted the Russian government and claimed they would call off the terror campaign if the Russian people were granted a constitution that provided free elections and an end to censorship. Tsar Alexander III rejected this proposal and instead decided to blame the Jews for his father's death. The government claimed that 30% of those arrested for political crimes were Jewish, as were 50% of those involved in revolutionary organisations, even though Jews were a mere 5% of the overall population. (27)

As one Jewish historian, David Rosenberg, has pointed out, the assassination of Alexander II heralded an outbreak of Anti-Semitism: "Within a few weeks, impoverished and vulnerable Jewish communities suffered a wave of pogroms - random mob attacks on their villages and towns, which the authorities were unwilling to prevent and were accused of unofficially instigating. In 1881, pogroms were recorded in 166 Russian towns." (28)

Over the next 25 years, more than a third of Russia's Jews left the country and large numbers settled in Britain. These people received a hostile reception from the right-wing press. (29) This included The Daily Mail: "On 2nd February, 1900, a British liner called the Cheshire moored at Southampton, carrying refugees from anti-semitic pogroms in Russia... There were all kinds of Jews, all manner of Jews. They had breakfasted on board, but they rushed as though starving at the food. They helped themselves at will, they spilled coffee on the ground in wanton waste.... These were the penniless refugees and when the relief committee passed by they hid their gold, and fawned and whined, and in broken English asked for money for their train fare." (30)

The Aliens Act was given royal assent in August 1905. It was the first time the government introduced immigration controls and registration, and gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for immigration and nationality matters. The government argued that the act was designed to prevent paupers or criminals from entering the country and set up a mechanism to deport those who slipped through. Alfred Eckhard Zimmern, was one of many who opposed the legislation as being anti-Semitic, commented: "It is true that it does not specify Jews by name and that it is claimed that others besides Jews will be affected by the Act, but that is only a pretence." (31)

David Rosenberg argues: "The Alien's Act drastically reduced the numbers of Jews seeking economic betterment in Britain who were permitted to enter; it also prevented greater numbers of asylum-seekers, escaping harrowing persecution, from finding refuge. In 1906, more than 500 Jewish refugees were granted political asylum. In 1908 the figure had fallen to twenty and by 1910, just five. During the same period, 1,378 Jews, who had been permitted to enter as immigrants but were found to be living on the streets without any visible means of support, had been rounded up and deported back to their country of origin." (32)

Lord Northcliffe

In April 1905, Alfred Harmsworth, established Associated Newspapers Limited with a capital of £1,600,000, the shares of which swiftly sold out. His income for the year was £115,000. Apart from his newspaper business he had other stock worth £300,000. Despite his growing wealth he was still dissatisfied and craved titles and acceptance from the ruling class. (33)

On 23rd June, it was announced that Harmsworth had received a baronetcy. The Daily Telegraph reported that it was unusual for a man "to win so much success in so limited a time". (34) Those newspapers that supported the Liberal Party were less complimentary. The Daily Chronicle stated that "Mr. Harmsworth's is the name of the most general interest in a list that is more remarkable for quantity than quality". (35) The most bitter comment came from The Daily News, "having been conspicuously passed over for several years, Sir Alfred Harmsworth has arrived at his baronetcy... for all he did during the Boer War." (36)

Arthur Balfour resigned as prime minister on 4th December 1905 and was replaced by Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the leader of the Liberal Party. Before he went he asked Edward VII if he would give Alfred Harmsworth a peerage. The Chief Whip, Alexander Acland-Hood, believed that if this did not happen, Harmsworth would change his support to the Liberals: "If he doesn't get it now he will get it when Cambell-Bannerman makes his Peers on taking office - we should then lose all his money and influence - I very much dislike the business, but as we can't stop it in the future why make so handsome a present to the other side!" (37)

Alfred Harmsworth took the title, Lord Northcliffe. Balfour told him that he was "the youngest peer" in British history. It was a very controversial decision and many considered it an act of corruption. A few years earlier Harmsworth had commented that "when I want a peerage I will pay for it" and that is what a lot of people thought had happened. Herbert Stern, a banker, was also accused of buying the title, Lord Michelham. (38)

The Saturday Review published a long article on Balfour's resignation list. Is it true or false that the peerages of Michelham and Northcliffe were sold for so much cash down? And did the cash go into the war-chest of the Conservative party? That these peerages were conferred for a sincere belief in the public merits of the recipients or from any other mercenary considerations is plainly incredible... Beginning the world with nothing he (Northcliffe) has made a very large fortune by the production of certain newspapers. No man makes a pile without the possession of certain qualities, which are obviously rare, but which do not in our opinion necessarily entitle their possessors to a seat in the House of Lords... We say advisedly that he has done more than any man of his generation to pervert and enfeeble the mind of the multitude." (39)

Alfred Gollin has argued that there were other reasons why some people objected to him becoming a member of the House of Lords: "A chief source of the hostility that confronted him lay in the fact that he (Alfred Harmsworth) was so different from the other members of the ruling class of his time. They resented his power, his influence, his ability, and most of all, his refusal to conform to their standards... the established classes were hostile to Lord Northcliffe because he came from a different background, because he had clawed his way to the top, because he was required, as an outsider, to have recourse to different methods when he sought to clutch at authority and grasp for power. The ordinary rulers of Britain were ruthless enough but a man of Northcliffe's type had to be harder, tougher, more openly brutal, or else he would perish". (40)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman called a general election and on 21st December, 1905, he made pledges to support Irish Home Rule, to cut defence spending, to repeal the 1902 Education Act, to oppose food taxes and slavery in South Africa. The Daily Mail reported that the Liberal Party intended to "attack capital, assail private enterprise, undo the Union, reverse the Education Act, cripple the one industry of South Africa, reduce the navy and weaken the army." It went on to say that if the Liberals won power it would bring a halt to the growth of the British Empire. (41)

During the campaign members of the Women Social & Political Union attempted to disrupt political meetings. On 10th January, 1906, The Daily Mail described these women as "suffragettes". It was meant as an insult but Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the organisation, liked the term and defiantly accepted the label. Lord Northcliffe, was totally opposed to women having the vote and ordered his editors to ignore their activities. (42)

Dreadnoughts or Old Age Pensions

In the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party won 397 seats (48.9%) compared to the Conservative Party's 156 seats (43.4%). The Labour Party, led by Keir Hardie did well, increasing their seats from 2 to 29. In the landslide victory Arthur Balfour lost his seat as did most of his cabinet ministers. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (43)

Balfour considered the growth in the vote for Labour a significant factor in the result."I am quite confident that there are much deeper causes at work than those with which, for the last 20 years, we have been familiar. I regard the enormous increase in the Labour vote (an increase which cannot be measured merely by the number returned of Labour members so-called) as a reflection in this country - faint I hope - of what is going on the Continent; and, if so, 1906 will be remarkable for something much more important than the fall of a Government which has been ten years in office." (44)

One of the innovations introduced by the Daily Mail was the publication of serials. Personally supervised by Northcliffe, the average length was 100,000 words. The opening episode was 5,000 words and had to have a dramatic impact on the readers. This was followed by episodes of 1,500 to 2,000 words every day. On 19th March 1906, the newspaper published the first installment of The Invasion of 1910, in which the novelist William Le Queux, detailed a German invasion of Britain.

This was all part of Lord Northcliffe's campaign to build up Britain's defences against Germany. He was a great supporter of the need to build up the British Navy to protect the country from a German invasion. Britain's first dreadnought was built at Portsmouth Dockyard between October 1905 and December 1906. It was the most heavily-armed ship in history. She had ten 12-inch guns (305 mm), whereas the previous record was four 12-inch guns. The gun turrets were situated higher than user and so facilitated more accurate long-distance fire. In addition to her 12-inch guns, the ship also had twenty-four 3-inch guns (76 mm) and five torpedo tubes below water. In the waterline section of her hull, the ship was armoured by plates 28 cm thick. It was the first major warship driven solely by steam turbines. It was also faster than any other warship and could reach speeds of 21 knots. A total of 526 feet long (160.1 metres) it had a crew of over 800 men. It cost over £2 million, twice as much as the cost of a conventional battleship.

Germany built its first dreadnought in 1907 and plans were made for building more. The British government believed it was necessary to have twice the number of these warships than any other navy. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the German Ambassador, Count Paul Metternich, and told him that Britain was willing to spend £100 million to frustrate Germany's plans to achieve naval supremacy. That night he made a speech where he spoke out on the arms race: "My principle is, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, less money for the production of suffering, more money for the reduction of suffering." (45)

Lord Northcliffe, used his newspapers to urge an increase in defence spending and a reduction in the amount of money being spent on social insurance schemes. In one letter to Lloyd George he suggested that the Liberal government was Pro-German. Lloyd George replied: "The only real pro-German whom I know of on the Liberal side of politics is Rosebery, and I sometimes wonder whether he is even a Liberal at all! Haldane, of course, from education and intellectual bent, is in sympathy with German ideas, but there is really nothing else on which to base a suspicion that we are inclined to a pro-German policy at the expense of the entente with France." (46)

Northcliffe's propaganda campaign was helped by the purchase of The Times newspaper on 16th March 1908 for £320,000, following a complex financial and political campaign in which he outmanoeuvred his rival, C. Arthur Pearson. He always claimed that he allowed the paper its full independence but he made sure that the senior staff agreed with him on the current political issues, especially, military spending. (47)

The Daily Mail and the Welfare State

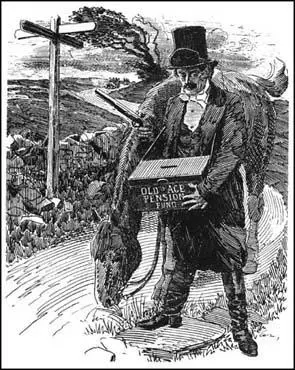

David Lloyd George was the leading radical in the Liberal government. In one speech had warned that if the government did not pass progressive measures, at the next election, the working-class would vote for the Labour Party: "If at the end of our term of office it were found that the present Parliament had done nothing to cope seriously with the social condition of the people, to remove the national degradation of slums and widespread poverty and destitution in a land glittering with wealth, if they do not provide an honourable sustenance for deserving old age, if they tamely allow the House of Lords to extract all virtue out of their bills, so that when the Liberal statute book is produced it is simply a bundle of sapless legislative faggots fit only for the fire - then a new cry will arise for a land with a new party, and many of us will join in that cry." (48)

Lloyd George had been a long opponent of the Poor Law in Britain. He was determined to take action that in his words would "lift the shadow of the workhouse from the homes of the poor". He believed the best way of doing this was to guarantee an income to people who were to old to work. Based on the ideas of Tom Paine that first appeared in his book Rights of Man, Lloyd George's proposed the introduction of old age pensions.

In a speech on 15th June 1908, he pointed out: "You have never had a scheme of this kind tried in a great country like ours, with its thronging millions, with its rooted complexities... This is, therefore, a great experiment... We do not say that it deals with all the problem of unmerited destitution in this country. We do not even contend that it deals with the worst part of that problem. It might be held that many an old man dependent on the charity of the parish was better off than many a young man, broken down in health, or who cannot find a market for his labour." (49)

To pay for these pensions Lloyd George had to raise government revenues by an additional £16 million a year. In 1909 Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new super-tax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5,000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. Other innovations in Lloyd George's budget included labour exchanges and a children's allowance on income tax. (50)

Lord Northcliffe disliked the idea of paying higher taxes in order to help provide old age pensions and used all of his newspapers to criticize the measures in the budget. The Daily News launched an attack on the wealthy men opposed to the budget: "It is they who own the newspapers, and when we remember that The Times, The Daily Mail, and The Observer, not to mention a host of minor organs in London and the provinces, are all controlled by one man, it is easy to realise how vast a political power capital exerts by this means alone." (51)

One of David Lloyd George's main supporters was Winston Churchill, who spoke at a large number of public meetings on this issue. Robert Lloyd George, the author of David & Winston: How a Friendship Changed History (2005) has suggested that their main motive was to prevent socialism in Britain: "Churchill and Lloyd George intuitively saw the real danger of socialism in the global situation of that time, when economic classes were so divided. In other European countries, revolution would indeed sweep away monarchs and landlords within the next ten years. But thanks to the reforming programme of the pre-war Liberal government, Britain evolved peacefully towards a more egalitarian society. It is arguable that the peaceful revolution of the People's Budget prevented a much more bloody revolution." (52)

The Conservatives, who had a large majority in the House of Lords, objected to this attempt to redistribute wealth, and made it clear that they intended to block these proposals. Lloyd George reacted by touring the country making speeches in working-class areas on behalf of the budget and portraying the nobility as men who were using their privileged position to stop the poor from receiving their old age pensions. The historian, George Dangerfield, has argued that Lloyd George had created a budget that would destroy the House of Lords if they tried to block the legislation: "It was like a kid, which sportsmen tie up to a tree in order to persuade a tiger to its death." (53)

On 30th November, 1909, the Peers rejected the Finance Bill by 350 votes to 75. H. H. Asquith had no option but to call a general election. In January 1910, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. John Grigg, the author of The People's Champion (1978) argues that the reason why the "people failed to give a sweeping, massive endorsement to the People's Budget" was that the electorate in 1910 was "by no means representative of the whole British nation". He points out that "only 58 per cent of adult males had the vote, and it is a fair assumption that the remaining 42 per cent would, if enfranchised, have voted in very large numbers for Liberal or Labour candidates. In what was still a disproportionately middle-class electorate the fear of Socialism was strong, and many voters were susceptible to the argument that the Budget was a first installment of Socialism." (54)

The historian, Duncan Tanner, believes that Lord Northcliffe played an important role in the election. Although the the Liberal Party had the support of two popular national newspapers, the Daily News and the Daily Chronicle, they found it difficult to compete with the influence of Northcliffe's Daily Mail. Tanner has pointed out: "They were enthusiastically progressive. They sensationally exposed poverty, making 'political' comparisons between the 'immoral' and 'extreme' wealth of Tory plutocrats and the landlords on the one hand, and the acute and total distress of the poor on the other. Yet between them they had less than three-quarters of a million readers in 1910 (less than the Tory Daily Mail alone)." (55)

The circulation of the Daily Mail in 1910 was 900,000. This gave them the advantage over The Daily Chronicle (800,000), The Daily Sketch (750,000), The Daily Mirror (630,000), The Daily Express (400,000), The Daily Telegraph (230,000), The Morning Post (50,000), The Times (45,000) and The Manchester Guardian (40,000). (56)

David Lloyd George became convinced that Britain needed a health insurance scheme similar to one introduced in Germany in the 1880s. Lloyd George presented his national insurance proposal to the Cabinet at the beginning of April, 1911. "Insurance was to be made compulsory for all regularly employed workers over the age of sixteen and with incomes below the level - £160 a year - of liability for income tax; also for all manual labourers, whatever their income. The rates of contribution would be 4d. a week from a man, and 3d. a week from a woman; 3d. a week from his or her employer; and 2d. a week from the State." (57)

The National Insurance Bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 4th May, 1911. Lloyd George argued: "It is no use shirking the fact that a proportion of workmen with good wages spend them in other ways, and therefore have nothing to spare with which to pay premiums to friendly societies. It has come to my notice, in many of these cases, that the women of the family make most heroic efforts to keep up the premiums to the friendly societies, and the officers of friendly societies, whom I have seen, have amazed me by telling the proportion of premiums of this kind paid by women out of the very wretched allowance given them to keep the household together."

Lloyd George went on to explain: "When a workman falls ill, if he has no provision made for him, he hangs on as long as he can and until he gets very much worse. Then he goes to another doctor (i.e. not to the Poor Law doctor) and runs up a bill, and when he gets well he does his very best to pay that and the other bills. He very often fails to do so. I have met many doctors who have told me that they have hundreds of pounds of bad debts of this kind which they could not think of pressing for payment of, and what really is done now is that hundreds of thousands - I am not sure that I am not right in saying millions - of men, women and children get the services of such doctors. The heads of families get those services at the expense of the food of their children, or at the expense of good-natured doctors."

Lloyd George stated this measure was just the start to government involvement in protecting people from social evils: "I do not pretend that this is a complete remedy. Before you get a complete remedy for these social evils you will have to cut in deeper. But I think it is partly a remedy. I think it does more. It lays bare a good many of those social evils, and forces the State, as a State, to pay attention to them. It does more than that... till the advent of a complete remedy, this scheme does alleviate an immense mass of human suffering, and I am going to appeal, not merely to those who support the Government in this House, but to the House as a whole, to the men of all parties, to assist us." (58)

The Observer welcomed the legislation as "by far the largest and best project of social reform ever yet proposed by a nation. It is magnificent in temper and design". (59) The British Medical Journal described the proposed bill as "one of the greatest attempts at social legislation which the present generation has known" and it seemed that it was "destined to have a profound influence on social welfare." (60)

Lloyd George's reforms were strongly criticised and some Conservatives accused him of being a socialist. There was no doubt that he had been heavily influenced by Fabian Society pamphlets on social reform that had been written by Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw. However, some Fabians "feared that the Trade Unions might now be turned into Insurance Societies, and that their leaders would be further distracted from their industrial work." (61)

Lloyd George pointed out that the labour movement in Germany had initially opposed national insurance: "In Germany, the trade union movement was a poor, miserable, wretched thing some years ago. Insurance has done more to teach the working class the virtue of organisation than any single thing. You cannot get a socialist leader in Germany today to do anything to get rid of that Bill... Many socialist leaders in Germany will say that they would rather have our Bill than their own." (62)

Lord Northcliffe, launched a propaganda campaign against the bill on the grounds that the scheme would be too expensive for small employers. The climax of the campaign was a rally in the Albert Hall on 29th November, 1911. As Lord Northcliffe, controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation, his views on the subject was very important.

H. H. Asquith was very concerned about the impact of the The Daily Mail involvement in this issue: "The Daily Mail has been engineering a particularly unscrupulous campaign on behalf of mistresses and maids and one hears from all constituencies of defections from our party of the small class of employers. There can be no doubt that the Insurance Bill is (to say the least) not an electioneering asset." (63)

Frank Owen, the author of Tempestuous Journey: Lloyd George and his Life and Times (1954) suggested that it was those who employed servants who were the most hostile to the legislation: "Their tempers were inflamed afresh each morning by Northcliffe's Daily Mail, which alleged that inspectors would invade their drawing-rooms to check if servants' cards were stamped, while it warned the servants that their mistresses would sack them the moment they became liable for sickness benefit." (64)

The National Insurance Bill spent 29 days in committee and grew in length and complexity from 87 to 115 clauses. These amendments were the result of pressure from insurance companies, Friendly Societies, the medical profession and the trade unions, which insisted on becoming "approved" administers of the scheme. The bill was passed by the House of Commons on 6th December and received royal assent on 16th December 1911. (65)

The Daily Mail and The Times, both owned by Lord Northcliffe, continued its campaign against the National Insurance Act and urged its readers who were employers not to pay their national health contributions. David Lloyd George asked: "Were there now to be two classes of citizens in the land - one class which could obey the laws if they liked; the other, which must obey whether they liked it or not? Some people seemed to think that the Law was an institution devised for the protection of their property, their lives, their privileges and their sport it was purely a weapon to keep the working classes in order. This Law was to be enforced. But a Law to ensure people against poverty and misery and the breaking-up of home through sickness or unemployment was to be optional." (66)

Lloyd George attacked the newspaper baron for encouraging people to break the law and compared the issue to the foot-and-mouth plague rampant in the countryside at the time: "Defiance of the law is like the cattle plague. It is very difficult to isolate it and confine it to the farm where it has broken out. Although this defiance of the Insurance Act has broken out first among the Harmsworth herd, it has travelled to the office of The Times. Why? Because they belong to the same cattle farm. The Times, I want you to remember, is just a twopenny-halfpenny edition of The Daily Mail." (67)

One of his journalists, Tom Clarke, pointed out that Lord Northcliffe dictated the political stance of his newspaper: "He (Northcliffe) was sometimes violent in both speech and action (once in his office he took a flying kick at the seat of the pants of a man who had annoyed him; and on another occasion put his foot through a man's hat in his temper). He seldom sought advice, and treated it so roughly if he did not like it, that people hesitated to give it him. When he spoke, everybody else listened, usually without challenge. He suffered from little opposition." (68)

Lord Northcliffe used his newspapers to oppose women having the vote. He ordered his newspapers to ignore the subject as he believed any publicity only helped their cause. On a visit to Canada and the United States he proudly pointed out that newspapers in those countries had more information on the activities of the National Union of Suffrage Societies and the Women Social & Political Union than the ones controlled by him. (69)

However, he thought it wise not to give his opinions in public as he feared it would lose him readers: "My view of the position of newspaper owners is that they should be read and not seen. The less they appear in person the better for the influence of their newspapers. That is why I never appear on public platforms. As to the woman's suffrage business, I am one of those people who believe the whole thing to be a bubble, blown by a few wealthy women who employ their less prosperous sisters to do the work. I judge public interest in the matter by the correspondence received. We never get any letters apart from those from the stage army of suffragettes." (70)

Lord Northcliffe was also extremely hostile to trade unions. One of his journalists remembered how he behaved during a strike organised by the National Union of Mineworkers: "During this coal strike the orders came thick and fast. Whatever he might do through The Times in the way of influencing public opinion, he could do far more through the Daily Mail, with its millions... He thought mob rule might be coming, so the mob must be divided; the public must be shown how the miners were enjoying themselves at the seaside or dog races while helpless workers in other industries suffered from the creeping paralysis." (71)

Lord Northcliffe and Germany

Lord Northcliffe had consistently described Germany as Britain's "secret and insidious enemy", and he commissioned Robert Blatchford, to visit Germany and then write a series of articles setting out the dangers. The German's, Blatchford wrote, were making "gigantic preparations" to destroy the British Empire and "to force German dictatorship upon the whole of Europe". He complained that Britain was not prepared for was and argued that the country was facing the possibility of an "Armageddon". (72)

He continued to demand that the government to spend more money on building up the British Navy. In this he gained the support of Reginald McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty, David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was totally opposed to this policy. He reminded H. H. Asquith of "the emphatic pledges given by us before and during the general election campaign to reduce the gigantic expenditure on armaments built up by our predecessors... but if Tory extravagance on armaments is seen to be exceeded, Liberals... will hardly think it worth their while to make any effort to keep in office a Liberal ministry... the Admiralty's proposals were a poor compromise between two scares - fear of the German navy abroad and fear of the Radical majority at home... You alone can save us from the prospect of squalid and sterile destruction." (73)

Lord Northcliffe was highly critical of a Liberal government who were more willing to spend more money on the emerging welfare state than on defence spending. In the 1910 General Election he accused the government of "surrendering to socialism" and that it was the patriotic duty of the British people to vote for the Conservative Party as Germany wanted a Liberal victory in the election. (74)

The Daily Mail campaigned for the introduction of military conscription to deal with the threat of Germany. It argued that "in recent years" no other subject "has attracted more attention, has aroused more discussion, or been followed by our readers with closer interest". It also published a pamphlet that dealt with this issue. Within a few weeks it sold over 1,600,000 copies. The Manchester Guardian accused the newspaper of "deliberately raking the fires of hell for votes". (75)

In January 1911, Lord Northcliffe met Geoffrey Dawson, who had worked very closely with Sir Alfred Milner in establishing the Round Table. According to Alexander May, "The aim of the Round Table was deceptively simple: to ensure the permanence of the British empire by reconstructing it as a federation representative of all its self-governing parts. Curtis depicted this as the logical outcome of the movement towards self-government in the dominions, and the only alternative to disruption and independence." Northcliffe agreed with Dawson's views on the British Empire and appointed him as a full-time staff member of The Times. He was invited to Northcliffe's Tudor mansion near Guildford. The two men, who were "strong Imperialists" got on very well. Northcliffe told a friend that Dawson would one day be "a future editor of The Times." (76)

David Lloyd George was constantly in conflict with Reginald McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty, and suggested to H. H. Asquith that his friend, Winston Churchill, should become First Lord of the Admiralty. Asquith took this advice and Churchill was appointed to the post on 24th October, 1911. McKenna, with the greatest reluctance, replaced him at the Home Office. This move backfired on Lloyd George as the Admiralty cured Churchill's passion for "economy". The "new ruler of the King's navy demanded an expenditure on new battleships which made McKenna's claims seem modest". (77)

The Admiralty reported to the British government that by 1912 Germany would have 17 dreadnoughts, three-fourths the number planned by Britain for that date. At a cabinet meeting David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill both expressed doubts about the veracity of the Admiralty intelligence. Churchill even accused Admiral John Fisher, who had provided this information, of applying pressure on naval attachés in Europe to provide any sort of data he needed. (78)

Admiral Fisher refused to be beaten and contacted King Edward VII about his fears. He in turn discussed the issue with H. H. Asquith. Lloyd George wrote to Churchill explaining how Asquith had now given approval to Fisher's proposals: "I feared all along this would happen. Fisher is a very clever person and when he found his programme in danger he wired Davidson (assistant private secretary to the King) for something more panicky - and of course he got it." (79)

Lord Northcliffe felt that George Earle Buckle, the editor of The Times, had not been vigorous enough in the campaign against Germany and on 31st July, 1912, he forced his resignation. He was replaced by Geoffrey Dawson. Northcliffe told Dawson: "Our task is great and worthy. If we get the barnacle-covered whale off the rocks & safely into deep water while we are comparatively young we may be able to keep it there until we discover others who can carry on the work." (80) According to Stephen E. Koss, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain (1984) Dawson seems to have "routinely acquiesced in Northcliffe's views and prejudices". (81)

The layout of the newspaper paper was redesigned and to make it more competitive, "the price was cut by half to one penny a copy". This was very successful and circulation rose dramatically from 47,000 in August 1912, when Dawson became editor. The first one-penny edition of the newspaper sold 281,000, but eventually settled down to an average 145,000 by the spring of 1914. (82)

Lord Northcliffe's newspapers continued to attack the Liberal government over its policies of progressive taxation, its apparently willingness to grant Irish Home Rule and the low-level of its defence spending. Northcliffe asked for a meeting with the prime minister. Asquith wrote to his confidante Venetia Stanley about the request: "He (Northcliffe) is anxious that I should see him. I hate and distrust the fellow and all his works... so I merely said that if he chose to ask me directly to see him, and he had anything really new to communicate, I would not refuse. I know of few men in this world who are responsible for more mischief, and deserve a longer punishment in the next." (83)

On 28th July, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Northcliffe admitted that war seemed inevitable but blamed the Liberal government for not spending enough money on the armed forces. C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, disagreed. "Not only are we neutral now, but we could, and ought to remain neutral throughout the whole course of the war... We wish Serbia no ill; we are anxious for the peace of Europe. But Englishmen are not the guardians of Serbia well being, or even of the peace of Europe. Their first duty is to England and to the peace of England... We care as little for Belgrade as Belgrade does for Manchester." (84)

The Daily Mail disagreed and reported: "The Austrian onslaught... will, it is to be feared, draw Russia into the field... in turn this will be followed by German action. Germany's entrance will compel France... When France is in peril, and fighting for her very existence, Great Britain cannot stand by and see her friend stricken down... We must stand by our friends, if for no other and heroic reason, because without their aid we cannot be safe. The failure to organise and arm the British nation so as to meet the new conditions of Europe has left us dependent on Foreign allies. We have forfeited our old independent position, and as the direct consequence we may be drawn into a quarrel with which we have no immediate concern. But at least we can be true to our duty today if we have neglected it in the past." (85)

At a Cabinet meeting on Friday, 31st July, more than half the Cabinet, including David Lloyd George, Charles Trevelyan, John Burns, John Morley, John Simon and Charles Hobhouse, were bitterly opposed to Britain entering the war. Only two ministers, Sir Edward Grey and Winston Churchill, argued in favour and H. H. Asquith appeared to support them. At this point, Churchill suggested that it might be possible to continue if some senior members of the Conservative Party could be persuaded to form a Coalition government.

On 3rd August, 1914, Germany declared war on France. That evening an estimated 30,000 people took to the streets. They gathered around Buckingham Palace and eventually King George V and the rest of the royal family appeared on the balcony. The crowd began singing "God Save the King" and then large numbers left to smash the windows of the German Embassy. Frank Owen points out that the previous day the crowds had been calling for a peaceful settlement of the crisis, now they were "clamouring for war". (86)

The following day the Germans marched into Belgium. According to the historian, A. J. P. Taylor: "At 10.30 p.m. on 4th August 1914 the king held a privy council at Buckingham Palace, which was attended only by one minister and two court officials. The council sanctioned the proclamation of a state of war with Germany from 11 p.m. That was all. The cabinet played no part once it had resolved to defend the neutrality of Belgium. It did not consider the ultimatum to Germany, which Sir Edward Grey, the foreign secretary, sent after consulting only the prime minister, Asquith, and perhaps not even him." (87)

Charles Trevelyan, John Burns, and John Morley, all resigned from the government. However, David Lloyd George continued to serve in the cabinet. Frances Stevenson, Lloyd George's private secretary, later claimed: "My own opinion is that Lloyd George's mind was really made up from the first, that he knew that we would have to go in and the invasion of Belgium was, to be cynical, a heaven-sent opportunity for supporting a declaration of war." (88)

The Daily Mail reported: "Europe might have been spared all this turmoil and anguish if Great Britain had only been armed and organised for war as the needs of our age demand. The precaution has not been taken, but in this solemn hour we shall utter no reproaches on that account. Our duty is to go forward into the valley of the shadow of death with courage and faith - with courage to suffer, with faith in God and our country." (89)

The First World War

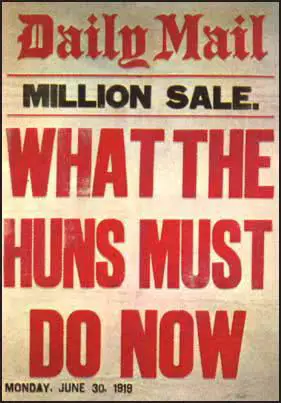

On the outbreak of the First World War the editor of The Star newspaper claimed that: "Next to the Kaiser, Lord Northcliffe has done more than any living man to bring about the war." Once the war had started Northcliffe used his newspaper empire to promote anti-German hysteria. It was The Daily Mail that first used the term "Huns" to describe the Germans and "thus at a stroke was created the image of a terrifying, ape-like savage that threatened to rape and plunder all of Europe, and beyond." (90)

As Philip Knightley, the author of The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth Maker (1982) has pointed out: "The war was made to appear one of defence against a menacing aggressor. The Kaiser was painted as a beast in human form... The Germans were portrayed as only slightly better than the hordes of Genghis Khan, rapers of nuns, mutilators of children, and destroyers of civilisation." (91) In one report the newspaper referred to Kaiser Wilhelm II as a "lunatic," a "barbarian," a "madman," a "monster," a "modern judas," and a "criminal monarch". (92)

Lord Northcliffe's main concern was a German invasion and was opposed to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) being sent to France. On 5th August, 1914, he warned Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, against any plan to dispatch the BEF. He told the editor of The Daily Mail: "I will not support the sending out of this country of a single British soldier. What about invasion? What about our own country? Put that in the leader... Say so in the paper tomorrow." (93)

However, Churchill ignored Northcliffe and it was decided that the 120,000 soldiers in the BEF should be sent to Maubeuge in France. "They (the Army Council) agreed that the fourteen Territorial divisions could protect the country from invasion. The BEF was free to go abroad. Where to? There could be no question of helping the Belgians, through this was why Great Britain had gone to war. The BEF had no choice: it must go to Maubeuge on the French left." (94)

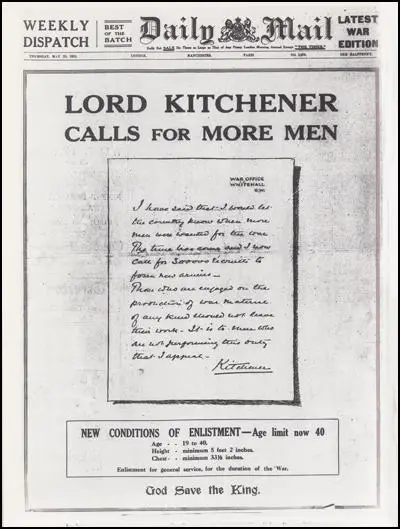

Over the last few months Lord Northcliffe's newspapers campaigned for Lord Kitchener to become Secretary of State for War. It claimed that this post might go to Richard Haldane, a man who Northcliffe believed was pro-German, who had been responsible for delaying war preparations. (95) However, Asquith eventually took Northcliffe's advice and gave Kitchener the post. According to George Arthur, Kitchener's biographer, became Secretary of War because of "the persistence of Lord Northcliffe". (96)

Lord Northcliffe believed that the intertwined national economies of 1914 could not stand more than a few months of conflict. Military experts agreed and predicted that the war would involve battles of movement, fought by professional armies which would be home by Christmas. Northcliffe expected the "British Navy would win the war for Britain by defeating the enemy fleet and blockading Germany". (97)

Kitchener disagreed with Northcliffe on this issue: A.J.P. Taylor has pointed out: "He (Lord Kitchener) startled his colleagues at the first cabinet meeting which he attended by announcing that the war would last three years, not three months, and that Great Britain would have to put an army of millions into the field. Regarding the Territorial Army with undeserved contempt, he proposed to raise a New Army of seventy divisions and, when Asquith ruled out compulsion as politically impossible, agreed to do so by voluntary recruiting." (98)

On 7th August, 1914, the House of Commons was told that Britain needed an army of 500,000 men. The same day Lord Kitchener issued his first appeal for 100,000 volunteers. He got an immediate response with 175,000 men volunteering in a single week. With the help of a war poster that featured Kitchener and the words: "Join Your Country's Army", 750,000 had enlisted by the end of September.

According to his biographer, Keith Neilson: "Kitchener brought to his new office both strengths and weaknesses. He had waged two wars in which he had dealt with all aspects of warfare, including both command and logistics. He was used to being in charge of large enterprises, he was not afraid to take responsibility and make decisions, and he enjoyed public confidence. However, he had no experience of modern European war, almost no knowledge of the British army at home, and a limited understanding of the War Office. Perhaps most importantly, he had no experience of working in a cabinet. Nevertheless in the opening stage of the war he, Asquith, and Churchill formed a dominant triumvirate in the cabinet." (99)

On 8th August 1914, the House of Commons passed the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) without debate. The legislation gave the government executive powers to suppress published criticism, imprison without trial and to commandeer economic resources for the war effort. During the war publishing information that was calculated to be indirectly or directly of use to the enemy became an offence and accordingly punishable in a court of law. This included any description of war and any news that was likely to cause any conflict between the public and military authorities.

The British government established the War Office Press Bureau under F. E. Smith. The idea was this organisation would censor news and telegraphic reports from the British Army and then issue it to the press. Lord Northcliffe was furious when he heard the news and complained to Smith about the situation. He replied: "We are bound to make mistakes at the start. Give me the advantage throughout of any advice which your experience suggests... Kitchener cannot understand that he is working in a democratic country. He rather thinks he is in Egypt where the press is represented by a dozen mangy newspaper correspondents whom he can throw in the Nile if they object to the way they are treated." (100)

The Daily Mail complained bitterly about the DORA regulations: "Public enthusiasm for our army is not being chilled by the insufficiency of news concerning the British troops at the front. The newspapers do not wish to publish... anything that might be injurious to the military interests of the nation... while we will agree that a careful censorship is necessary for success, it might seem that the reticence in Great Britain has been carried to an unnecessary extreme." (101)

Lord Kitchener, the War Minister, was determined not to have any journalists reporting the war from the Western Front. He instead appointed Colonel Ernest Swinton, to write reports on the war. These were then vetted by Kitchener before being sent to the newspapers. Lord Northcliffe ignored this attempt at press censorship and sent two of his journalists, Hamilton Fyfe and Arthur Moore to France.

On 30th August, 1914, The Times published a report on the problems faced by the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. "The German advance has been one of almost incredible rapidity... The Germans, fulfilling one of the best of all precepts in war, never gave the retreating army one single moment's rest. The pursuit was immediate, relentless, unresting. Aeroplanes, Zeppelins, armoured motors, were loosed like an arrow from the bow... Regiments were grievously injured, and the broken army fought its way desperately with many stands, forced backwards and ever backwards by the sheer unconquerable mass of numbers... Our losses are very great. I have seen the broken bits of mass regiments... The German commanders in the north advance their men as if they had an inexhaustible supply." (102)

In the House of Commons, William Llewelyn Williams asked H. H. Asquith was aware of the report that British forces had suffered a major defeat in France. The prime minister replied: "It is impossible too highly to commend the patriotic reticence of the Press as a whole from the beginning of the war up to the present moment. The publication to which my honourable friend refers appears to be a very regrettable exception - and I hope it will not recur... The Government feel after the experience of the last two weeks that the public is entitled to information - prompt and authentic information - of what is happening at the front, and which they hope will be more adequate." (103)

Winston Churchill wrote to Lord Northcliffe and complained about the article: "I think you ought to realize the damage that has been done by Sunday's publication in the Times. I do not think you can possibly shelter yourself behind the Press Bureau, although their mistake was obvious. I never saw such panic-stricken stuff written by any war correspondent before; and this served up on the authority of the Times can be made, and has been made, a weapon against us in every doubtful state." (104)

Lord Northcliffe replied: "This is not a time for Englishmen to quarrel... Nor will I discuss the facts and tone of the message, beyond saying that it came from one of the most experienced correspondents in the service of the paper. I understand that not a single member of the staff on duty last Saturday night expected to see it passed by the Press Bureau." He then pointed out that it was not only passed but carefully edited and it seemed that the government actually wanted it to published. (105)

To circumvent the Press Bureau, the Northcliffe newspapers often quoted American journals. For example, on 4th December, 1914, the Daily Mail carried excerpts from the Saturday Evening Post that quoted Lord Kitchener as saying that Britain would need at least three more years to defeat Germany. (106) Sir Stanley Buckmaster at the Press Bureau, asked the government to use DORA to court-martial Lord Northcliffe. This idea was rejected by the government. It was claimed that David Lloyd George was Northcliffe's greatest defender and GR argued that there was "no doubt some sort of understanding between him and Northcliffe." (107)

Some journalists were already in France when war was declared in August 1914. Philip Gibbs, a journalist working for The Daily Chronicle, quickly attached himself to the British Expeditionary Force and began sending in reports from the Western Front. When Lord Kitchener discovered what was happening he ordered the arrest of Gibbs. After being warned that if he was caught again he "would be put up against a wall and shot", Gibbs was sent back to England. (108)

The result of Lord Kitchener's policy was that during the early stages of the war British journalists in France were treated as outlaws. They could be arrested at any time and by any officer, either French or British who discovered them. Kitchener gave orders that any correspondent found would be immediately arrested, expelled and have his passport cancelled. "under these conditions it was difficult for the war correspondents to get reports and messages to their newspapers." (109)

Basil Clarke of The Daily Mail later recalled: "I count it among my achievements that I was never once arrested. The difficulties were numerous. Even to live in the war zone without papers and credentials was hard enough, but to move about and see things, and pick up news and then to get one's written dispatches conveyed home - against all regulations - was a labour greater and more complex than anything I have ever undertaken in journalistic work. I longed sometimes to be arrested and sent home and done with it all." (110)

Lord Northcliffe was determined to make The Daily Mail the official newspaper of the British Army. Every day 10,000 copies of the paper were delivered to the Western Front by military motor cars. He also had the revolutionary idea of using front-line soldiers as news sources. Soon after the outbreak of war he announced a scheme where he would pay for letters sent to their families by serving soldiers. (111)

Northcliffe's newspapers were willing to publish stories about German "atrocities" in Belgium and France. On 17th August 1914 the Daily Mail carried accounts of how German soldiers had murdered five civilians. (112) A few days later Hamilton Fyfe chronicled the "sins against civilization" and the "barbarity" of the Germans. He also wrote a story about how Germans had cut off the hands of Red Cross workers and had used women and children as shields in battle". (113)

This was followed by a fuller account of the atrocities: "The measured, detailed, and we fear unanswerable indictment of Germany's conduct of the war issued yesterday by the Belgian minister is a catalogue of horrors that will indelibly brand the German name in the eyes of all mankind.. This is no ordinary arraignment... concerned not with hearsay evidence, but with incidents that in each case have been carefully investigated... After making every deduction for national bias and the possibility of error, there remains a record of sheer brutality that will neither be forgiven or forgotten." (114)

Robert Graves, who served on the Western Front, raised doubts about the truth of these stories, in his book on the war, Goodbye to All That: "French and Belgian civilians had often tried to win our sympathy by exhibiting mutilations of children - stumps of hands and feet, for instance - representing them as deliberate, fiendish atrocities when, as likely as not, they were merely the result of shell-fire. We did not believe rape to be any more common on the German side of the line than on the Allied side. And since a bully-beef diet, fear of death, and absence of wives made ample provision of women necessary in the occupied areas, no doubt the German army authorities provided brothels in the principal French towns behind the line, as the French did on the Allied side. We did not believe stories of women's forcible enlistment in these establishments. What's wrong with the voluntary system? we asked cynically." (115)

During the early stages of the conflict Lord Northcliffe created a great deal of controversy by advocating conscription and criticizing Lord Kitchener. In an article he wrote on 21st May, 1915, Northcliffe wrote a blistering attack on the Secretary of State for War: "Lord Kitchener has starved the army in France of high-explosive shells. The admitted fact is that Lord Kitchener ordered the wrong kind of shell - the same kind of shell which he used largely against the Boers in 1900. He persisted in sending shrapnel - a useless weapon in trench warfare. He was warned repeatedly that the kind of shell required was a violently explosive bomb which would dynamite its way through the German trenches and entanglements and enable our brave men to advance in safety. This kind of shell our poor soldiers have had has caused the death of thousands of them." (116)

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Repington, the chief war correspondent of The Times, was a close friend of the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, Sir John French, and was invited to visit the Western Front. Repington now had growing influence over military policy and one politician described him as "the twenty-third member of the Cabinet". During the offensive at Artois, Repington was shown confidential information about the British Army being short of artillery shells. (117)

On 14th May, 1915, the newspaper published the contents of a telegram sent by Repington: "The attacks (on Sunday last in the districts of Fromelles and Richebourg) were well planned and valiantly conducted. The infantry did splendidly, but the conditions were too hard. The want of an unlimited supply of high explosives was a fatal bar to our success at Festubert." (118)

The Daily Mail now launched an attack on Lord Kitchener and under the heading "British Still Struggling: Send More Shells" it argued that the newspaper was in a very difficult position for if it published "the truth about the defects of our military preparations". It claimed that under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) the newspaper could be accused of aiding the enemy; and if it didn't, it was not fulfilling its responsibility to keep the public informed of the situation. (119)

Lord Northcliffe decided to make a direct on Lord Kitchener for not supplying enough high-explosive shells. In an article he published on 21st May, 1915, Northcliffe wrote a blistering attack on the Secretary of State for War: "Lord Kitchener has starved the army in France of high-explosive shells. The admitted fact is that Lord Kitchener ordered the wrong kind of shell - the same kind of shell which he used largely against the Boers in 1900. He persisted in sending shrapnel - a useless weapon in trench warfare. He was warned repeatedly that the kind of shell required was a violently explosive bomb which would dynamite its way through the German trenches and entanglements and enable our brave men to advance in safety. This kind of shell our poor soldiers have had has caused the death of thousands of them." (120)

The following day The Daily Mail continued the attack. The paper stated that "our men at the Front have been supplied with the wrong kind of shell and the result has been a heavy and avoidable loss of life". A shortage of shells at the beginning of the conflict was understandable and excusable, but the inability of officials to supply adequate munitions after ten months for Britain's fighting men was "proof of grave negligence". (121)

Lord Kitchener was a national hero and Northcliffe's attack on him upset a great number of readers. Overnight, the circulation of The Daily Mail dropped from 1,386,000 to 238,000. A placard was hung across The Daily Mail nameplate with the words "The Allies of the Huns". Over 1,500 members of the Stock Exchange had a meeting where they passed a motion against the "venomous attacks of the Harmsworth Press" and afterwards ceremoniously burnt copies of the offending newspaper. (122)

The editor of the newspaper, Thomas Marlowe, informed Lord Northcliffe of the more than one million drop in circulation. He was also given a copy of The Star that defended Kitchener from Northcliffe's attacks. Northcliffe responded by arguing: "I don't know what you men think and I don't care. The Star is wrong, and I am right. And the day will come when you will all know that I am right." (123)

Lord Northcliffe wrote to Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of the The Times: "Nearly every day in some part or other of The Times appears a puff of Kitchener... Lloyd George assures me that this man is the curse of the country. He gave me example after example on Sunday night of the loss of life due to this man's ineptitude. Is it not possible to keep his name out of the paper." (124)

Although the leader of the government, H.H Asquith, accused Northcliffe and his newspapers of disloyalty, he privately accepted that shell production was a real problem and he appointed David Lloyd George as the new Munitions Minister. "He (Lloyd George) believed he was the man - perhaps the only man - who could win the war." (125) S. J. Taylor has argued: "David Lloyd George was installed as Minister of Munitions, and it was generally believed his appointment was what Northcliffe had intended all along. Certainly, Lloyd George brought to the newly created position the energy, competence and cynicism it required." (126)

In the spring of 1916 Herbert Asquith decided to send Lord Kitchener to Russia in an attempt to rally the country in its fight against Germany. On 5th June 1916, Kitchener was drowned when the HMS Hampshire on which he was traveling to Russia, was struck a mine off the Orkneys. When he heard the news Lord Northcliffe remarked: "The British Empire has just had the greatest stroke of luck in its history.... Providence is on the side of the British Empire after all." (127) Lloyd George also believed that the death of Kitchener was "at the best possible moment for the country". (128)

Military Conscription

Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. Over 750,000 had enlisted by the end of September, 1914. Thereafter the average ran at 125,000 men a month until the summer of 1915 when numbers joining up began to slow down. Leo Amery, the MP for Birmingham Sparkbrook pointed out: "Every effort was made to whip up the flagging recruiting campaign. Immense sums were spent on covering all the walls and hoardings of the United Kingdom with posters, melodramatic, jocose or frankly commercial... The continuous urgency from above for better recruiting returns... led to an ever-increasing acceptance of men unfit for military work... Throughout 1915 the nominal totals of the Army were swelled by the maintenance of some 200,000 men absolutely useless for any conceivable military purpose." (129)

The British had suffered high casualties at the Marne (12,733), Ypres (75,000), Gallipoli (205,000), Artois (50,000) and Loos (50,000). The British Army found it difficult to replace these men. In May 1915 135,000 men volunteered, but for August the figure was 95,000, and for September 71,000. Asquith appointed a Cabinet Committee to consider the recruitment problem. Testifying before the Committee, Lloyd George commented: "I would say that every man and woman was bound to render the services that the State they could best render. I do not believe you will go through this war without doing it in the end; in fact, I am perfectly certain that you will have to come to it." (130)

The shortage of recruits became so bad that George V was asked to make an appeal: "At this grave moment in the struggle between my people and a highly-organized enemy, who has transgressed the laws of nations and changed the ordinance that binds civilized Europe together, I appeal to you. I rejoice in my Empire's effort, and I feel pride in the voluntary response from my subjects all over the world who have sacrificed home, fortune, and life itself, in order that another may not inherit the free Empire which their ancestors and mine have built. I ask you to make good these sacrifices. The end is not in sight. More men and yet more are wanted to keep my armies in the field, and through them to secure victory and enduring peace.... I ask you, men of all classes, to come forward voluntarily, and take your share in the fight". (131)

Lord Northcliffe now began to advocate conscription (compulsory enrollment). On 16th August, 1915, the Daily Mail published a "Manifesto" in support of national service. (132) The Conservative Party agreed with Lord Northcliffe about conscription but most members of the Liberal Party and the Labour Party were opposed to the idea on moral grounds. Some military leaders objected because they had a "low opinion of reluctant warriors". (133)

Asquith "did not oppose it on principle, though he was certainly not drawn to it temperamentally and had intellectual doubts about its necessity." Lloyd George had originally had doubts about the measure but by 1915 "he was convinced that the voluntary system of recruitment had served its turn and must give way to compulsion". (134) Asquith told Maurice Hankey that he believed that "Lloyd George is out to break the government on conscription if he can." (135)

Lloyd George threatened to resign if Asquith did not introduce conscription. Eventually he gave in and the Military Service Bill was introduced by Asquith on 21st January 1916. John Simon, the Home Secretary, resigned and so did Arthur Henderson, who had represented the Labour Party in the coalition government. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of the Daily News argued that Lloyd George was engineering the conscription crisis in order to substitute himself for Asquith as leader of the country." (136)

Lord Northcliffe received a large number of threatening letters because of his compulsion campaign. Tom Clarke, who worked for Northcliffe, saw the contents of these letters, commented that one said: "Warning to Lord Northcliffe... If the compulsion Bill is passed you are a dead man. I and another half-dozen young men have made a pledge - that is, to shoot you like a dog. We know where to find you." (137)

In a speech he made in Conwy Lloyd George denied that he was involved in any plot against Asquith: "I have worked with him for ten years. I have served under him for eight years. If we had not worked harmoniously - and we have - let me tell you here at once that it would have been my fault and not his. I have never worked with anyone who could be more considerate... But we have had our differences. Good heavens, of what use would I have been if I had not differed from him? Freedom of speech is essential everywhere, but there is one place where it is vital, and that is in the Council Chamber of the nation. The councillor who professes to agree with everything that falls from the leader betrays him."