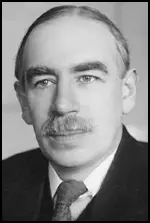

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, the eldest of three children, was born on 5th June 1883 at 6 Harvey Road, Cambridge. His father, John Neville Keynes was an economist who taught at Cambridge University. His mother, Florence Keynes had been educated at Newnham College and was the city's first woman mayor. His father inherited money just before his marriage and the family lived very comfortably. (1)

Alexander Cairncross, has pointed out: "The family kept three servants - a cook, a parlour maid, and a nursery maid - and there was a German governess. In his first few years Maynard was a sickly child, suffering to begin with from frequent attacks of diarrhoea and thereafter from feverishness... In the summer of 1889 he had an attack of rheumatic fever and a few months later he had to give up attending his kindergarten for a time, suffering from what was diagnosed as St Vitus's dance." (2)

In 1897 Keynes was entered for the Eton College scholarship examination and attained the tenth out of fifteen places and was first equal in mathematics. Keynes was a prodigious prize winner at Eton. He won 10 in his first year, 18 in the second, 11 in his third. His brother, Geoffrey Keynes, commented that his father "set great store by our marks and position in class, and this stimulated a sense of competition in Maynard, who enjoyed his own capacity of leaping ahead of other boys." (3)

John Maynard Keynes at Cambridge University

In his final year Keynes won an Eton scholarship to King's College, in mathematics and classics. One of his tutors was Alfred Marshall. He also came under the influence of George Edward Moore, who was ten years his senior. Moore was a Fellow of Trinity College. Keynes wrote after attending one of Moore's lectures: "I have undergone conversation, I am with Moore absolutely and on all things - even secondary qualities... Something gave in my brain and I saw everything clearly in a flash." In another letter, he wrote "one hardly feels prepared to disagree with Moore on everything." (4)

Keynes was invited to join the Apostles, a small, secret society of dons and undergraduates who met to discuss ethical and political issues. He was initiated into the Society in February, 1903. (5) The group included Lytton Strachey, Bertrand Russell, Roger Fry, Leonard Woolf and E. M. Forster. Russell later commented: "It was owing to the existence of the Society that I soon got to know the people best worth knowing." (6)

Alec Cairncross has attempted to explain the beliefs of the Apostles: "The key difference in the attitude of Keynes and his friends was that the basis of the calculus of moral action was seen as exclusively personal, not as rules imposed from without. There could be no objective measure of what was good since, if the good consisted of states of mind, these states could be known and judged only by the minds in question. Duty, action, social need simply did not enter. Intuitive judgements were all one could turn to." (7)

Keynes friendship with Woolf and Russell brought him into contact with leaders of the Fabian Society, including Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb and George Bernard Shaw. He also became friends with Rupert Brooke, another member of the Fabians. Unlike most of his friends, Brooke was "strongly heterosexual". When he visited Brooks he "found him sitting in the midst of admiring female Fabians with nothing on but an embroidered sweater." (8)

John Maynard Keynes remained a strong supporter of the Liberal Party. He made his first contribution to the Cambridge Union Debating Society on 4th November 1902. The President of the Union, Edwin Montagu, was so impressed that he invited him to be one of the main speakers a fortnight later. Montagu was taken more by Keynes's logic than by his delivery, which was not impressive. He also met Edward Grey who was senior figure in the party. He told his friend, Bernard Swithinbank, whom he considered Grey a "very commanding and reliable statesman" and admitted that he had become "quite political... a most amusing game and a very fairly adequate substitute for bridge". (9)

Gerald Mackworth Young at Cambridge University.

Keynes most important friend in the first few years at university was Lytton Strachey. In the usual pattern of his close friendships Keynes dominated. "He was cleverer, more articulate, more worldly, more practical than his friends... In his friendship with Strachey, the roles were reversed. Strachey was three years older than Keynes and a much more formed and definite character. He did not become a professional philosopher, but he had a very sharp, analytical, mind, even being to hold his own with Bertrand Russell. Strachey was a philosopher of the tastes and the emotions." Strachey loved clever people and he fell passionately in love with Keynes. (10)

Strachey told Ralph Partridge that Keynes was an "immensely interesting figure - partly because, with his curious typewriter intellect, he's also so oddly and unexpectedly emotional". In another letter he argued that "I don't believe he has any very good feelings, but perhaps one's inclined to think that more than one ought because he's so ugly. Perhaps experience of the world at large may improve him." (11)

Strachey wrote to Leonard Woolf: "There can be no doubt that we are friends. His conversation is extraordinarily alert and very amusing. He sees at least as many things as I do - possibly more. He's interested in people to a remarkable degree. He doesn't seem to be in anything aesthetic, though his taste is good. His presence of character is really complete. He analyses with amazing persistence and brilliance. I have never met so active a brain. His conversation is extraordinarily alert and very amusing. He's interested in people to a remarkable degree." (12)

The two men fell out over a new young student, Arthur Lee Hobhouse. Strachey wrote to Woolf, detailing his beauty: "Hobhouse is fair, with frizzy hair, a good complexion, an arched nose, and a very charming expression of countenance. His conversation is singularly coming on... He's interested in metaphysics and people, he's not a Christian and he sees quite a lot of jokes. I'm rather in love with him, and Keynes who lunched with him today... is convinced that he's all right... he looks pink and delightful as embryos should." (13)

In January 1905, Strachey told Keynes he was love with Hobhouse. He was therefore furious when Keynes began a sexual relationship with the young man. (14) On 29th March, Keynes and Hobhouse went on holiday together for three weeks. Strachey told him that when he heard that "I hated you like hell". However, after he returned to Cambridge, Keynes wrote to Strachey explaining that "all I will say is that at the moment I am more madly in love with him, than ever and that we have sailed into smooth waters - for how long I know not." (15)

Hobhouse was the first love of Keynes's adult life. However, Hobhouse had doubts about the sexual aspects of the relationship. He told James Strachey, "I couldn't help suffering a revulsion". Over the next few months Keynes confided his "ups and downs" with Hobhouse to Strachey. Keynes confessed that "I have a clear head, a weak character, an affectionate disposition and a repulsive appearance." By his confidences Keynes won back Strachey's love. "It's only when he's shattered by a crisis that I seem to be able to care for him." (16)

In his diary Keynes kept a detailed account of his sex life. Johannes Lenhard points out: "Keynes was an obsessively methodical man; even as a child he counted the number of front steps of every house on his street, and, later on in life, kept a running record of his golf scores. Unable to shake such an ingrained character trait, Keynes even counted and tabulated his sex life.... Between 1906 and 1915, Keynes consistently enjoyed the company of about fifteen constantly changing sexual partners and additionally engaged in over a hundred anonymous sex acts." (17)

Keynes developed a close intellectual relationship with Bertrand Russell. Keynes told Lytton Strachey that he had seen Russell give a "superb display" in arguing with Leonard Hobhouse, a journalist with the Manchester Guardian. (18) Russell also had great respect for Keynes's intellect. "It was the sharpest and clearest that I have ever known. When I argued with him, I felt that I took my life in my hands, and I seldom emerged without feeling something of a fool." (19) He also enjoyed the conversation of George Bernard Shaw who Keynes "converted us all to socialism". However, he remained an active member of the Liberal Party. (20)

The India Office

After completing his degree in 1905 Keynes took the Civil Service Examination. He came second, with 3,498 marks out of a possible 6,000. Otto Niemeyer, a classical scholar from Balliol College with 3,917. He wrote to Lytton Strachey explaining his results: "My marks have arrived and left me enraged. Really knowledge seems an absolute bar to success. I have done worst in the only two subjects of which I possessed a solid knowledge, Mathematics and Economics. My dear, I scored more marks for English history than for mathematics - is it credible? For economics I got a relatively low percentage and was 8th or 9th in order of merit - whereas I knew the whole of both papers in a really elaborate way. On the other hand in Political Science, to which I devoted less than a fortnight in all, I was easily first of everybody. I was first in Logic and Psychology, and in Essay." (21)

On 16th October 1906 Keynes started his civil service career as junior clerk in the Military Department of the India Office, at a salary of £200 a year. "Keynes had chosen the India Office because it was one of the two top home departments of state, not because he had any interest in India. Certainly his attitude to British rule was conventional in every sense. He believed the regime protected the poor against the rapacious money-lender, brought justice and material progress, and gave the country a sound monetary system: in short, introduced good government to places which could not develop it on their own." (22)

In February 1907, Keynes was offered him promotion with more money but he rejected it on the grounds that it would interfere with the writing of his dissertation. However, the following month he was transferred to the Revenue, Statistics and Commerce Department. This involved him reading government reports: "Some of it is quite absorbing - Foreign Office commercial negotiations with Germany, quarrels with Russia in the Persian Gulf, the regulation of opium in Central India, the Chinese opium proposals - I have had great files to read on all these in the last two days." His job was to report back to leading figures in the Civil Service: "Yesterday I attended my first Committee of Council. The thing is simply government by dotardry; at least half those present showed manifest signs of senile decay, and the rest didn't speak." (23)

Keynes continued work on his fellowship dissertation on probability. "It was a subject that had been neglected for a generation by philosophers, and economists seemed content to leave it to the statisticians." (24) This involved reading books on the subject in other languages: "I find that the rate of speed with English, French and German is about in the ratio of 1:2:3 - which makes the reading of the 3,000 or 4,000 pages of German I see ahead of me rather a labour." (25)

During this period he became friends with Mary Sheepshanks. While at Newnham College she began to teach adult literacy classes in the poor working-class district of Barnwell. This experience turned her into a social reformer and a supporter of women's suffrage and an active member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Votes for women was a political cause which aroused some enthusiasm among the Apostles. In 1907 Bertrand Russell stood for parliament in a by-election at Wimbledon as a candidate for women's suffrage. Keynes was also a supporter and acted as chief steward at NUWSS meetings. (26)

In July 1907, John Maynard Keynes went on a walking holiday with his brother, Geoffrey Keynes, and Roger Fry, a fellow member of the Bloomsbury Group. Keynes wrote to Lytton Strachey about his holiday: "Fay is only a qualified success... Fortunately we like him, so it is not a failure but Fay, being absolutely the worst walker and mountaineer I have ever seen, either delays us for hours, or has to be left behind... He is too ugly. Ugliness of face, hands, body, clothes and manners are not, I find, completely overbalanced by cheerfulness, a good heart, and an average intelligence." (27)

The following month Keynes began an affair with Strachey's boyfriend, Duncan Grant. On 29th June, Grant wrote to Keynes saying: "I know I needn't tell you how much I enjoyed my Cambridge visit... indeed I don't think I have ever been so completely happy, anyhow since I left school." (28) It did not take long before Strachey discovered what was going on. Strachey told Keynes: "I hear that you and Duncan are carrying on together." (29)

According to Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1995): "Of all the amorous crises sprinkled through his life, this was perhaps the most wretched. It came as a complete shock. The two points between which his unstable emotional existence had been delicately poised were rooted up. Adding to his agony was the realization that he had been made to look so foolish. As he retraced the pattern of events in his mind, it was this thought which tormented him most." (30)

It was not long before Strachey forgave Keynes for his relationship with Grant. He also took the blame for the conflict: "Such a dazzled and gibbering creature as I am! However, you seem to have put up with that hitherto and I daresay you will in the future. Dear Maynard, I only know that we've been friends for too long to stop being friends now. There are some things that I shall try not to think of, and you must do your best to help me in that; and you must believe that I do sympathise and don't hate you and that if you were here now I should probably kiss you, except then Duncan would be jealous, which would never do!" (31)

After his fellowship dissertation on probability was completed he was appointed as a lecturer in Economics. On hearing the news, Thomas Holderness, his head of department, wrote to Keynes: "I have never been quite able to satisfy myself that a government office in this country is the best thing for a young man of energy and right ambitions. It is a comfortable means of life and leads by fairly sure, if slow, stages to moderate competence and old age provisions. But it is rarely exciting or strenuous and does not make sufficient call on the combative and self-assertive elements of human nature." (32)

John Maynard Keynes, like most economists at the time, started teaching economics without having taken a university degree in the subject. His first task was to read the work of Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill. The main textbook he used with his teaching was written by Alfred Marshall, the man who had appointed him to the post. Principles of Economics (1890) had been the dominant economic textbook in England since the end of the 19th century. (33)

John Maynard Keynes became editor of The Economic Journal in 1912 and his first book Indian Currency and Finance was published in 1913. This was based on lectures he had delivered at the London School of Economics two years previously. Meanwhile the government had decided to set up a royal commission on Indian finance and currency, on which Keynes was asked to act full-time as secretary. When he asked for freedom to publish his book the offer was changed to one of a seat on the commission and he took his place on it at just under thirty years of age. Keynes made a deep impression on the other members of the commission, including the chairman, Sir Austen Chamberlain. (34)

First World War

In January 1915 John Maynard Keynes was recruited to the Treasury, after pressure from Edwin Montagu, who had witnessed his talent in the India Office. It was through Montagu that he was introduced to H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George and Reginald McKenna. Keynes was highly critical of Lloyd George and wrote that he "never had the faintest idea of the meaning of money". He also had no problems telling "Lloyd George to his face" that his views on French finance were "rubbish". (35)

The shortage of recruits in 1915 became so bad that George V was asked to make an appeal: "At this grave moment in the struggle between my people and a highly-organized enemy, who has transgressed the laws of nations and changed the ordinance that binds civilized Europe together, I appeal to you. I rejoice in my Empire's effort, and I feel pride in the voluntary response from my subjects all over the world who have sacrificed home, fortune, and life itself, in order that another may not inherit the free Empire which their ancestors and mine have built. I ask you to make good these sacrifices. The end is not in sight. More men and yet more are wanted to keep my armies in the field, and through them to secure victory and enduring peace.... I ask you, men of all classes, to come forward voluntarily, and take your share in the fight". (36)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, the press baron, now began to advocate conscription (compulsory enrollment). On 16th August, 1915, the Daily Mail published a "Manifesto" in support of national service. (37) The Conservative Party agreed with Lord Northcliffe about conscription but most members of the Liberal Party and the Labour Party were opposed to the idea on moral grounds. Some military leaders objected because they had a "low opinion of reluctant warriors". (38)

Asquith "did not oppose it on principle, though he was certainly not drawn to it temperamentally and had intellectual doubts about its necessity." Lloyd George had originally had doubts about the measure but by 1915 "he was convinced that the voluntary system of recruitment had served its turn and must give way to compulsion". (39) Asquith told Maurice Hankey that he believed that "Lloyd George is out to break the government on conscription if he can." (40)

This put Keynes in a difficult position as most of his friends were conscientious objectors. Keynes worked through Philip Morrell and sympathetic ministers such as Reginald McKenna to attempt to ensure that the Military Service Bill would be amended to protect the rights of conscientious objectors. Keynes had thoughts of resigning, but decided "to stay until they actually begin to torture my friends." (41)

One of his friends, Clive Bell recorded: "Keynes was a conscientious objector... To be sure he was an objector of a peculiar and, as I think, most reasonable kind. He was not a pacifist; he did not object to fighting in any circumstances; he objected to conscription. He would not fight because Lloyd George, Horatio Bottomley and Lord Northcliffe told him to." (42)

When he received his call-up pages, he replied on Treasury writing-paper: "I claim complete exemption because I have a conscientious objection to surrendering my liberty of judgment on so vital a question as undertaking military service. I do not say that there are not conceivable circumstances in which I should voluntarily offer myself for military service. But after having regard to all the actually existing circumstances, I am certain that it is not my duty so to offer myself, and I solemnly assert to the Tribunal that my objection to submit to authority in this matter is truly conscientious." (43) According to Roy Harrod: "This appears to have quelled the authorities, for he was troubled by them no more." (44)

One of Keynes' friends, Kingsley Martin, was a pacifist who was totally opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. A conscientious objector, he refused to serve in the armed forces but was willing to carry out non-military duties. After a few months working as a medical orderly in a British hospital treating wounded soldiers, Martin joined the Society of Friends' Ambulance Unit (FAU) and later that year was working on the Western Front. He was critical of Keynes refusal to take a stand on the war. He quoted fellow conscientious objector, Bertrand Russell, who claimed that Keynes' work at the Treasury "consisted of finding ways of killing the maximum number of Germans at the minimum expense". (45)

During the war Keynes spent most weekends at Garsington Manor the home of Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell, both members of the Union of Democratic Control, an organization that soon emerged at the most important of all the anti-war groups in Britain. Grasington became a refuge for conscientious objectors. They worked on the property's farm as a way of escaping prosecution. (46)

Three members of the group, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and David Garnett, lived together at Charleston Farmhouse, near Firle. It also became a meeting place for a group of intellectuals described as the Bloomsbury Group. Other members included Virginia Woolf, Clive Bell, E. M. Forster, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Gerald Brenan, Ralph Partridge, Vita Sackville-West, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley. It was an ideal weekend place - only an hour by train from London. Keynes paid his first visit to what he described as "Duncan's new country house" at the end of October, 1916. (47)

David Lloyd George

At a meeting in Paris on 4th November, 1916, David Lloyd George came to the conclusion that the present structure of command and direction of policy could not win the war and might well lose it. Lord Northcliffe joined with Lloyd George in attempting to persuade H. H. Asquith and several of his cabinet, including Sir Edward Grey, Arthur Balfour, Robert Crewe-Milnes, 1st Marquess of Crewe and Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, to resign. It was reported that Lloyd George was trying to encourage Asquith to establish a small War Council to run the war and if he did not agree he would resign. (48)

Tom Clarke, the news editor of The Daily Mail, claims that Lord Northcliffe told him to take a message to the editor, Thomas Marlowe, that he was to run an article on the political crisis with the headline, "Asquith a National Danger". According to Clarke, Marlowe "put the brake on the Chief's impetuosity" and instead used the headline "The Limpets: A National Danger". He also told Clarke to print pictures of Lloyd George and Asquith side by side: "Get a smiling picture of Lloyd George and get the worst possible picture of Asquith." Clarke told Northcliffe that this was "rather unkind, to say the least". Northcliffe replied: "Rough methods are needed if we are not to lose the war... it's the only way." (49)

Those newspapers that supported the Liberal Party, became concerned that a leading supporter of the Conservative Party should be urging Asquith to resign. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of The Daily News, objected to Lord Northcliffe's campaign against Asquith: "If the present Government falls, it will fall because Lord Northcliffe decreed that it should fall, and the Government that takes its place, no matter who compose it, will enter on its task as the tributary of Lord Northcliffe." (50)

At a Cabinet meeting on the 5th December, 1916, Asquith refused to form a new War Council that did not include him. Lloyd George immediately resigned: "It is with great personal regret that I have come to this conclusion.... Nothing would have induced me to part now except an overwhelming sense that the course of action which has been pursued has put the country - and not merely the country, but throughout the world the principles for which you and I have always stood throughout our political lives - is the greatest peril that has ever overtaken them. As I am fully conscious of the importance of preserving national unity, I propose to give your Government complete support in the vigorous prosecution of the war; but unity without action is nothing but futile carnage, and I cannot be responsible for that." (51)

Conservative members of the coalition made it clear that they would no longer be willing to serve under Asquith. At 7 p.m. he drove to Buckingham Palace and tendered his resignation to King George V. Apparently, he told J. H. Thomas, that on "the advice of close friends that it was impossible for Lloyd George to form a Cabinet" and believed that "the King would send for him before the day was out." Thomas replied "I, wanting him to continue, pointed out that this advice was sheer madness." (52)

Asquith, who had been prime minister for over eight years, was replaced by Lloyd George. He brought in a War Cabinet that included only four other members: George Curzon, Alfred Milner, Andrew Bonar Law and Arthur Henderson. There was also the understanding that Arthur Balfour attended when foreign affairs were on the agenda. Lloyd George was therefore the only Liberal Party member in the War Cabinet. Keynes was appalled by these events and once again considered resigning. (53)

Lloyd George also disliked Keynes for making it clear that he disagreed with him over certain issues. He explained in a letter to his mother: "I was approved and included in the final list to get a C.B. (Companion of the Bath) this honours list. But when Lloyd George saw it he took his pen and struck my name out - an unheard of proceeding. Partly revenge for the McKenna War Council Memorandum against him, of which he knows I was the author." (54)

However, he was highly valued by Sir Robert Chalmers, the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, and he was placed in charge of a new department that dealt with all questions of External Finance. By the end of the war Keynes had a staff of seventeen people. Andrew McFadyean, was a young member of his department and recalled that it was exhilarating to see a "razor-sharp mind dissecting a problem and stating it in terms which made it look simple, and in language which it was a joy to read.... he was a prodigiously fast worker, and there was never much in his in-tray at the end of the day." (55)

The First World War was having a disastrous impact on the Russian economy. Food was in short supply and this led to rising prices. On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar Nicholas II. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. On 12th March the Tsar abdicated. Keynes, like many left-wing intellectuals, was "immensely cheered and excited him" and told his mother "it's the sole result of the war so far worth having". (56)

John Maynard Keynes got on well with Andrew Bonar Law, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer. In May 1917 Keynes was created Companion of the Bath, Third Class. He told his father that he received the honour "through the kindness of Chalmers who exerted the strongest possible pressure through the Chancellor of the Exchequer and made mine the sole name put forward by the Treasury". (57)

Keynes and Chalmers found themselves in conflict with Walter Cunliffe, the Governor of the Bank of England, after the United States withdrew funds from London for investment in a $2 billion Liberty Loan. "Again it fell to Keynes to handle the situation and obtain funds from the US at the very last moment. Friction with the Bank of England, which shared management of the exchange rate through a committee of bankers without responsibility for the borrowing operations this entailed, came to a head in July 1917, just after the exchange crisis was resolved. Cunliffe, the governor, demanded the dismissal of Keynes and Chalmers (the permanent secretary)". Bonar Law refused and instead sacked Cunliffe." (58)

John Maynard Keynes believed that the British government should negotiate a peace agreement with Germany. Keynes rejected Lloyd George's commitment to total victory, and feared its consequences. In a letter to Duncan Grant he claimed that "I work for a government I despise for ends I think criminal". (59) Robert Skidelsky argued: "The Prime Minister's remarkable political skills aroused in him only aesthetic and moral repugnance. He lived in the hope that Lloyd George's deviousness would prove his undoing. He fantasized about the downfall of his class which had so nervelessly placed supreme power in the hands of an adventurer." (60)

On the 9th May, 1918, Keynes wrote to his mother: "If this government were to beat the Germans, I should lose all faith for the future in the efficacy of intellectual processes... Everything is always decided for some reason other than the real merits of the case, in the sphere with which I have contact... Still and even more confidently I attribute our misfortunes to Lloyd George. We are governed by a crook and the results are natural. In the meantime old Asquith who I believe might yet save us is more and more of a student and lover of slack country life and less and less inclined for the turmoil. (61)

By August 1918, it was clear that the latest German offensive had failed and on 4th October the new German government of Max von Baden, asked for an armistice on the basis of the Fourteen Points announced by President Woodrow Wilson. Lloyd George was totally opposed to several of the points as he believed that Wilson was trying to undermine the country's ability to protect the British Empire. Keynes wrote to his mother: "I still think the prospects of peace good. But I suspect a possibility of wickedness on our part and an unwillingness to subscribe to the whole of Wilson's fourteen commandments." (62)

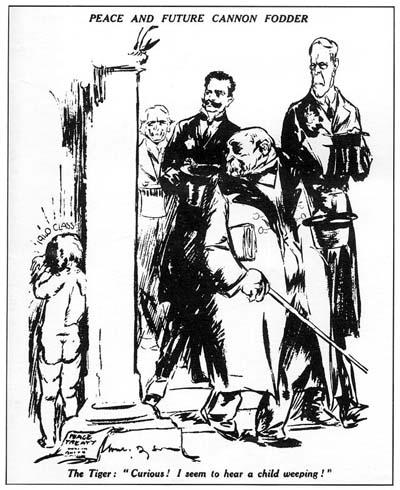

Paris Peace Conference

On 21st November, 1918, ten days after Germany's surrender, Keynes wrote to his mother, "I have been put in principal charge of financial matters for the Peace Conference". (63) The Paris Peace Conference opened in January 1919. Keynes produced a memorandum that suggested that the British should ask for £4,000m in reparations. The treasury document emphasized that this represented damage "done directly" to the civilian population - mainly destruction of civilian life and property through enemy action. However, Keynes suggested that the maximum Germany could pay was estimated at £3,000m; and an actual payment of £2,000m would be "a very satisfactory achievement in all the circumstances". The memorandum concluded that "if Germany is to be 'milked', she must not first of all be ruined". (64)

David Lloyd George put in a claim for £25 billion of reparations at the rate of £1.2 billion a year. Georges Clemenceau wanted £44 billion, whereas Woodrow Wilson said that all Germany could afford was £6 billion. On 20th March 1919, Lloyd George explained to Wilson that it would be difficult to "disperse the illusions which reign in the public mind". He had of course been partly responsible for this viewpoint. He was especially worried about having to "face up" to the "400 Members of Parliament who have sworn to exact the last farthing of what is owing to us." (65)

Lloyd George argued that Germany should pay the costs of widows' and disability pensions, and compensation for family separations. John Maynard Keynes was totally opposed to the idea. (66) He argued that if reparations were set at a crippling level the banking system, certainly of Europe and probably of the world, would be in danger of collapse. (67) Lloyd George replied: "Logic! Logic! I don't care a damn for logic. I am going to include pensions." (68)

Philip Kerr, 11th Marquess of Lothian, also advised Lloyd George against demanding too much from Germany: "You may strip Germany of her colonies, reduce her armaments to a mere police force and her navy to that of a third rate power, all the same if she feels that she has been unjustly treated in the peace of 1919, she will find means of exacting retribution from her conquerors... The greatest danger that I see in the present situation is that Germany may throw in her lot with Bolshevism and place her resources, her brains, her vast organising powers at the disposal of the revolutionary fanatics whose dream is to conquer the world for Bolshevism by force of arms." (69)

When it was rumoured that Lloyd George was willing to do a deal closer to the £6 billion than the sum proposed by the French, The Daily Mail began a campaign against the Prime Minister. This included publishing a letter signed by 380 Conservative backbenchers demanding that Germany pay the full cost of the war. "Our constituents have always expected and still expect that the first edition of the peace delegation would be, as repeatedly stated in your election pledges, to present the bill in full, to make Germany acknowledge the debt and then discuss ways and means of obtaining payment. Although we have the utmost confidence in your intentions to fulfil your pledges to the country, may we, as we have to meet innumerable inquiries from our constituents, have your renewed assurances that you have in no way departed from your original intention." (70)

Lloyd George made a speech in the House of Commons where he argued that it was wrong to suggest that he was willing to accept a lower figure. He ended his speech with an attack on Lord Northcliffe, who he accused of seeking revenge for his exclusion from the government. "Under these conditions I am prepared to make allowance, but let me say that when that kind of diseased vanity is carried to the point of sowing dissension between great allies whose unity is essential to the peace of the world... then I say, not even that kind of disease is a justification for so black a crime against humanity." (71)

Negotiations continued in Paris over the level of reparations. The Australian prime minister, William Hughes, joined the French in claiming the whole cost of the war, his argument being that the tax burden imposed on the Allies by the German aggression should be regarded as damage to civilians. He estimated the cost of this was £25 billion. John Foster Dulles, commented that in his opinion, Germany should only pay about £5 billion. Faced with the possibility of an American veto, the French abandoned their claims to war costs, being impressed by Dulles's argument that, having suffered the most damage, they would get the largest share of reparations. (72)

David Lloyd George eventually agreed that he been wrong to demand such a large figure and told Dulles he "would have to tell our people the facts". John Maynard Keynes suggested to Edwin Montagu that whereas Germany should be required to "render payment for the injury she has caused up to the limit of her capacity" but it was "impossible at the present time to determine what her capacity was, so that the fixing of a definite liability should be postponed." (73)

Keynes explained to Jan Smuts that he believed the Allies should take a new approach to negotiations: "This afternoon... Keynes came to see me and I described to him the pitiful plight of Central Europe. And he (who is conversant with the finance of the matter) confessed to me his doubt whether anything could really be done. Those pitiful people have little credit left, and instead of getting indemnities from them, we may have to advance them money to live." (74)

On 28th March, 1919, Keynes warned Lloyd George about the possible long-term economic problems of reparations. "I do not believe that any of these tributes will continue to be paid, at the best, for more than a very few years. They do not square with human nature or march with the spirit of the age." He also thought any attempt to collect all the debts arising from the First World War would poison, and perhaps destroy, the capitalist system. (75)

Keynes argued that it was in the best interest of the future of capitalism and democracy for the Allies to deal swiftly with the food shortages in Germany: "A proposal which unfolds future prospects and shows the peoples of Europe a road by which food and employment and orderly existence can once again come their way, will be a more powerful weapon than any other for the preservation from the dangers of Bolshevism of that order of human society which we believe to be the best starting point for future improvement and greater well-being." (76)

Eventually it was agreed that Germany should pay reparations of £6.6 billion (269bn gold marks). Keynes was appalled and considered that the figure should be around £2 billion. He wrote to Duncan Grant: "I've been utterly worn out, partly by incessant work and partly by depression at the evil round me... The Peace is outrageous and impossible and can bring nothing but misfortune... Certainly if I were in the Germans' place I'd die rather than sign such a Peace... If they do sign, that will really be the worst thing that could happen, as they can't possibility keep some of the terms, and general disorder and unrest will result everywhere. Meanwhile there is no food or employment anywhere, and the French and Italians are pouring munitions into Central Europe to arm everyone against everyone else... Anarchy and Revolution is the best thing that can happen, and the sooner the better." (77)

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28th June 1919. Keynes wrote to Lloyd George explaining why he was resigning: "I can do no more good here. I've on hoping even though these last dreadful weeks that you'd find some way to make of the Treaty a just and expedient document. But now it's apparently too late. The battle is lost. I leave the twins to gloat over the devastation of Europe, and to assess to taste what remains for the British taxpayer." (78)

After resigning and returning to England he wrote to his mother: "On Monday I began to write a new book... on the economic condition of Europe as it now is, including a violent attack on the Peace Treaty and my proposals for the future... I was stirred into it by the deep and violent shame which one couldn't help feeling for the events of Monday, and my temper may not keep up high enough to carry it through." (79)

It has been argued by Robert Skidelsky: "He (Keynes) had resigned from the Treasury in 'misery and rage' - a misery and rage which had been building up right through the war. It was compounded of the moral strain of working for a war he did not believe in, and of the guilt at having prospered, while his friends had suffered, for the views which they had jointly held. These emotions give his writing its tension, its moral and stylistic force." (80)

Over the next few months he settled down to a regular routine at Charleston Farmhouse. He breakfasted at 8 a.m., and wrote till lunch time. After lunch he read The Times, did the gardening and wrote letters. He wrote to Duncan Grant: "Most of the day I think about my book, and write it for about two hours, so that I get on fairly well and am now nearly half-way through the third chapter of eight. But writing is very difficult... I've finished today a sketch of the appearance and character of Clemenceau, and am starting tomorrow on Wilson. I think it's worthwhile to try, but it's really beyond my powers." (81)

The Economic Consequences of the Peace was published on 12th December 1919. The main theme of the book was about how the war had damaged the delicate economic mechanism by which the European peoples had lived before 1914, and how the Treaty of Versailles, far from repairing this damage, had completed the destruction. It praised the economic growth in the 19th century. "In Europe, the interference of frontiers and tariffs was reduced to a minimum... Over this great area there was an almost absolute security of property and person." (82)

Keynes warned that the belligerent governments had been forced by war to embark on a ruinous course of inflation, which was potentially fatal for capitalist civilisation. He argued that by inflation governments confiscate wealth arbitrarily and thus strike at the "confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth". Those who do well out of inflation become the objects of hatred of those "whom the inflationism has impoverished". Keynes quoted Lenin as saying that "there is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency". Keynes warned that if inflation was not dealt with, it could result in the overthrow of the capitalist system. (83)

Keynes pointed out that Germany could only pay reparations only by means of an export surplus, which would give it the foreign exchange to pay its annual tribute. However, in the five years before the war Germany's adverse balance of trade averaged £74m a year. By increasing its exports and reducing its imports Germany might in time be able to generate an annual export surplus of £50m, equivalent to £100m at post-war prices. Spread over thirty years this would come to a capital sum of £1,700m, invested at 6 per cent a year. Adding to this £100m-£200m available from transfers of gold, property, etc., he concluded that "£2,000m is a safe maximum figure of Germany's capacity to pay". (84)

Keynes outlined his alternative economic peace treaty: German damages limited to £2,000m; cancellation of inter-Allied debts; creation of a European free trade area and an international loan to stabilise the exchanges. If these remedies were not adopted: "Nothing can then delay for long that final civil war between the forces of reaction and the despairing convulsions of revolution, before which the horrors of the late German war will fade into nothing, and which will destroy, whoever is victor, the civilisation and the progress of our generation." (85)

The Economic Consequences of the Peace was criticised in France. Raphael Georges-Levy argued that Germany could readily pay what the Allies claimed. Henri Brenier accused Keynes of understating Germany's pre-war production, and minimizing the damage Germany had done to France's occupied regions. On the question of Germany's capacity to pay the accepted French view was that the right course was to fix a large capital sum and adjust the annual payments from time to time in the light of Germany's enlarging export capacity. As Robert Skidelsky pointed out: "This rather missed the point, for Germany would have no incentive to enlarge its exports, if the addition was to be confiscated." (86)

The Liberal and Labour press praised the book. John Lawrence Hammond, in the Manchester Guardian, accepted Keynes's view that "the economic losses inflicted on Germany made it absolutely impossible for her to carry out the terms of the Treaty". (87) Arthur Cecil Pigou, one of Britain's leading economists, congratulated Keynes on his "absolutely splendid and quite unanswerable argument". (88) Kingsley Martin, a committed socialist, who was a student at the time: "It was wonderful for us to have a high authority saying with inside knowledge of the Treaty what we felt emotionally". (89)

Conservative newspapers hated the book. The Sunday Chronicle called Keynes a representative of "a certain... dehumanised intellectual point of view" which failed to accept that Germany had to be punished. (90) Others accused him of being guilty of not showing "wholesome partisanship". (91) The Spectator rejected Keynes's ideas and argued: "The International Financial Conference has carefully inquired into all the facts, and it has come to the conclusion that it is well within your capacity to pay that amount. Now get to work. Under the system of credit which has been arranged there is nothing to stop you. The sooner you earn the necessary amount and pay it over to us, the sooner you will recover your complete independence, your comfort, and your self-respect." (92)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, had argued in The Daily Mail that David Lloyd George had been too soft on the Germans and was putting "the cost of the war on the backs of the British people". Northcliffe claimed that Lloyd George had given in to the pressure of German financial agents. "It is a deplorable thing that after all our sufferings and the sacrifices of all the gallant boys that have gone that in the end we should be beaten by financiers." (93)

Northcliffe also instructed Henry Wickham Steed, the editor of The Times, to criticise Keynes's book. He argued that Keynes's ideas was a misplaced revolt of economics against politics: "If the war taught us one lesson above all others it was that the calculations of economists, bankers, and financial statesmen who preached the impossibility of war because it would not pay were perilous nonsense... Germany went to war because she made it pay in 1870-71, and believed she could make it pay again." (94)

The Economic Consequences of the Peace was very successful and established his name as a leading economist. By 22nd April 1920, 18,500 had been sold in England, and nearly 70,000 in the United States. Two months later it was reported that world sales were well over 100,000, and the book had been translated into German, Dutch, Flemish, Danish, Swedish, Italian, Spanish, Rumanian, Russian, Japanese and Chinese. His English profits, at three shillings a copy, came to £3,000 and there was £6,000 from his American sales. His income rose from £1,802 in the tax-year 1918-1919 to £5,156 in the year 1919-20. (95)

John Maynard Keynes returned to teach at Cambridge University after the war. His first two sets of lectures in 1919 and 1920 attracted large audiences. Many of these people were not studying economics but wanted to hear what was wrong with the world. In fact, King's College only took half a dozen economic students every year. He also established the Keynes Club. Membership was by invitation only and consisted of his closest colleagues, graduate students and the best of the second and third year undergraduates. The proceedings were modelled on those of the Apostles. Someone, usually Keynes, would read a paper, then lots were drawn giving the order in which members had to make comments on it. (96)

In October 1921 he was invited by C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, to edit a series of supplements discussing the economic and financial problem of European reconstruction. There were eventually twelve monthly supplements, to which he contributed thirteen articles, and recruited a highly impressive list of contributors from many different countries, including some of the leading continental economists. (97)

Keynes's interests were increasingly directed towards what would later be called "the management of the economy". Two forms of economic instability preoccupied him. "Of these the first was instability of prices, inflation, deflation, and all that went with them; the second was unemployment and the fluctuations in economic activity giving rise to it. The two were, of course, interconnected since the movement of prices reacted on the level of activity: but the analytical approach to the problem of inflation, for example, was very different from the analysis necessary for an explanation of unemployment." (98)

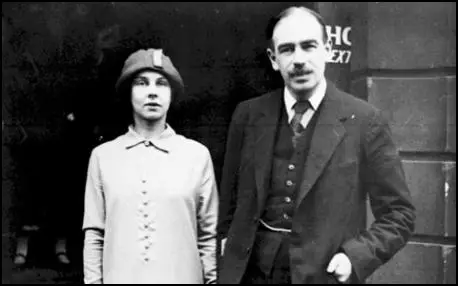

Lydia Lopokova

Keynes always had a strong interest in ballet. When he initially saw Lydia Lopokova he was unimpressed: "she's a rotten dancer - she has such a stiff bottom". (99) When he saw her again in December, 1921 in other Sergei Diaghilev ballets, including The Sleeping Princess, he fell deeply in love with her and they began a romantic relationship. He wrote to Vanessa Bell that "Loppy (Lydia Lopokova) came to lunch last Sunday, and I again fell very much in love with her. She seems to me perfect in every day. One of her new charms is the most knowing and judicious use of English words." (100) She replied that he should not marry her. (101).

The dance critic Cyril W. Beaumont, pointed out that Lydia had great charm: "Under medium height, she had a compact, well formed little body... Her hair was very fair, fluffed out at the forehead, and gathered in a little bun at the nape of her neck. She had small blue eyes, pale plump cheeks, and a curious nose, something like a humming-bird's beak, which gave a rare piquancy to her expression. She had a vivacious manner, alternating with moods of sadness. She spoke English well, with an attractive accent, and had a habit of making a profound remark as though it were the merest badinage. And I must not forget her silvery laugh... She had an ingenuous manner of talking, but she was very intelligent and witty, and, unlike some dancers, her conversation was not limited to herself and the Ballet." (102)

However, most of his friends, were opposed to the relationship. According to Margot Fonteyn: "When Keynes began to think of marriage, some of his friends were filled with foreboding. They tended to find Lopokova bird-brained. In reality she was intelligent, wise, and witty, but not intellectual... She artfully used, and intentionally misused, English to unexpectedly comic and often outrageous effect. Keynes was constantly amused and enchanted."

Robert Skidelsky has attempted to explain the attraction: "His sexual and emotional fancy was seized by free spirits. The two great loves of his life, Duncan and Lydia, were both uneducated; their reactions were spontaneous, fresh, unexpected. Keynes was not looking for an inferior model of himself, but a complement, or balance, to his own intellectuality... He was a gambler, and Lydia was his greatest gamble." (103)

Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994) pointed out that Duncan Grant, his former lover, had good reason to object to the proposed marriage: "Perhaps Duncan Grant had some excuse for resenting the emergence of a second great love into Maynard's life. But it was the others who were really malicious. As Maynard's mistress, Lydia had added something childlike and bizarre to Bloomsbury - she was a more welcome visitor than Clive's over-chic mistress Mary Hutchinson. But don't marry her... . If he did so Lydia would give up her dancing, Vanessa warned, become expensive, and soon bore him dreadfully. But what Vanessa and the other Charlestonians chiefly minded was Lydia's effect as Maynard's wife on Bloomsbury itself. Living a quarter-of-a-mile from Charleston at Tilton House on the edge of the South Downs, she would sweep in and stop Vanessa painting - and these interruptions were always so scatterbrained!" (104)

The Gold Standard

During the 19th century all the main countries of the world adhered to a fixed-exchange rate system known as the Gold Standard. "Their domestic currencies were freely convertible into specified amounts of gold; they maintained fixed proportions between the quantity of money in circulation and the gold reserves of their central banks. An ounce of gold was worth 3.83 pounds sterling and dollars 18.60, giving a sterling-dollar exchange rate of 4.86. The appeal of the gold standard was that it provided not just exchange rate stability, which encouraged international trade, but promised long-run stability in prices, since the obligation to maintain convertibility acted as a check on the 'over-issue' of notes by governments." (105)

By the 20th century the gold standard was seen as providing stability, low interest rates and a steady expansion in world trade. On the outbreak of the First World War Germany immediately left the gold standard. Britain followed soon afterwards. In financing the war and abandoning gold, many of the belligerents suffered serious problems with inflation. Price levels doubled in Britain, tripled in France and quadrupled in Italy. The economist, Richard G. Lipsey, has pointed out that the gold standard could not cope with the consequences of a world war. (106)

Under the terms of the Versailles Treaty the Allies confiscated Germany's gold supplies. They were therefore unable to return to the gold standard. During the Occupation of the Ruhr the German central bank (Reichsbank) issued enormous sums of non-convertible marks to support workers who were on strike against the French occupation and to buy foreign currency for reparations; this led to the German hyper-inflation of the early 1920s and helped to undermine confidence in the country's financial system. It also provided a warning of what could happen when a country managed its own currency. (107)

Winston Churchill rejoined the Conservative Party and on 6th November, 1924 Stanley Baldwin appointed him as Chancellor of the Exchequer. His biographer, Clive Ponting pointed out that he "had no experience of financial or economic matters". He had "taken virtually no interest in such questions and the only ideas on economic policy he was known to advocate were free trade and sound finance". Ponting adds that "he was, unusually for him, lacking in self-confidence on economic policy and proved much more willing to accept conventional wisdom and the advice of experts." (108)

Otto Niemeyer, Controller of Finance at the Treasury, and Montagu Norman, Governor of the Bank of England, and a handful of bankers argued that Churchill should return to the gold standard. Churchill had discussions with John Maynard Keynes and Reginald McKenna, chairman of the Midland Bank, who were both against the move. The Federation of British Industry, favoured postponement. Industrialists were not consulted, Norman commented that their views on the subject was comparable to asking shipyard workers what they thought about the "design of a battleship." (109)

According to Percy J. Grigg, Churchill's private secretary, at a meeting on 17th March, 1925, Keynes told the Chancellor of the Exchequer, that a return to the gold standard would result in an increase in "unemployment and downward adjustment of wages and prolonged strikes in some of the heavy industries, at the end of which it would be found that these industries had undergone a permanent contraction". It was therefore "better to keep domestic prices and nominal wage rates stable and allow the exchanges to fluctuate for the time being." (110)

Churchill found Keynes arguments convincing. He told Niemeyer he was concerned about the attitude of the Governor of the Bank of England: "The Treasury have never, it seems to me, faced the profound significance of what Mr Keynes calls the 'paradox of unemployment amidst dearth'. The Governor shows himself perfectly happy at the spectacle of Britain possessing the finest credit in the world simultaneously with a million and a quarter unemployed. It is impossible not to regard the object of full employment as at least equal, and probably superior, to the other valuables objectives you mention... The community lacks goods, and a million and a quarter people lack work. It is certainly one of the highest functions of national finance to bridge the gulf between the two." (111)

Despite these concerns, on 28th April, 1925, Churchill announced the return to the gold standard in the House of Commons. Churchill fixed the price at the pre-war rate of $4.86. "If we had not taken this action the whole of the rest of the British Empire would have taken it without us, and it would have come to a gold standard, not on the basis of the pound sterling, but a gold standard of the dollar." (112)

Keynes offered Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of The Times, a series of articles on the effects of the return to the gold standard. When he saw them he turned them down: "They are extraordinary clever and very amusing; but I really feel that, published in The Times at this particular moment, they would do harm and not good." (113) William Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, was more receptive and the articles appeared in the Evening Standard, in July, 1925. This was followed by a pamphlet, The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill. (114)

Keynes argued: "Our troubles arose from the fact that sterling's value had gone up by 10 per cent in the previous year. The policy of improving the exchange by 10 per cent involves a reduction of 10 per cent in the sterling receipts of our export industries". But they could not reduce their prices by 10 per cent and remain profitable unless all internal prices and wages fell by 10 per cent. "Thus Mr. Churchill's policy of improving the exchange by 10 per cent was, sooner or later, a policy of reducing everyone's wages by 2s. in the pound." Keynes went on to suggest that workers would be "justified in defending themselves" because they had no guarantee that they would be compensated later by a lower cost of living. (115)

Selina Todd pointed out in The People: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class (2014): "Churchill wanted to raise the value of the pound against other national currencies; a morale boost for those who recalled Britain's imperial pre-eminence in the years before 1914 but - as the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted - disastrous for the British economy. In 1914 Britain's government and industrialists had been able to rely on the empire both to produce and consume British goods. But by 1925 British industrialists relied heavily on exporting goods, and manufactures had to price their goods competitively in the free international market. Churchill's move made exports prohibitively expensive." (116)

It has been argued that Churchill overvalued sterling by at least ten per cent. "Domestically the results were disastrous. The overvalued pound meant the costs had to be reduced in an unavailing attempt to keep exports competitive and this at a time when real wages were already below 1914 levels. Attempts to impose further wage reductions inevitably led to industrial disputes, lock-outs, strikes, rising unemployment and increased social strains. The overvalued pound made perhaps as many as 700,000 people unemployed. The impact showed up the 1925 decision for what it was - a banking and financial policy designed to benefit the City of London." (117)

Marriage

John Maynard Keynes married Lydia Lopokova on 4th August 1925 (the year of her divorce from Randolfo Barocchi) at St Pancras Registry Office. The wedding received a considerable amount of publicity. For example, Vogue Magazine included a full-page picture with the caption: "The marriage of the most brilliant of English economists with the most popular of Russian dancers makes a delightful symbol of the mutual dependence upon each other of art and science." (118)

They visited the Soviet Union on their honeymoon. His biographer, Alexander Cairncross, has argued: "The marriage proved a great success and was a turning point in Keynes's life. Lopokova had gifts to which Bloomsbury was blind and she had a firm hold on his affections. When apart they wrote every day and she took charge of him in his illnesses and in wartime, when his energies had to be carefully husbanded. The couple had no children." The couple lived at 46 Gordon Square and Tilton House near Firle in East Sussex. (119)

Beatrice Webb believed his marriage to Lydia Lopokova changed his views on politics: "Hitherto he (John Maynard Keynes) has not attracted me - brilliant, supercilious, and not sufficiently patient for sociological discovery even if he had the heart for it, I should have said. But then I had barely seen him; also I think his love marriage with the fascinating little Russian dancer has awakened his emotional sympathies with poverty and suffering. For when I look around I see no other man who might discover how to control the wealth of nations in the public interest. He is not merely brilliant in expression and provocative in thought; he is a realist: he faces facts and he has persistency and courage in thought and action." (120)

John Maynard Keynes and the Liberal Party

At the time of his marriage Keynes wrote an article about his political beliefs. He was a strong opponent of the Conservative Party: "They offer me neither food nor drink - neither intellectual nor spiritual consolation... the mentality, the view of life of - well, I will not mention names - promotes neither my self-interest nor the public good. It leads nowhere; it satisfies no ideal; it conforms to no intellectual standard; it is not even safe, or calculated to preserve from spoilers that degree of civilisation which we have already attained."

He considered joining the Labour Party: "Superficially that is more attractive. But looked at closer, there are great difficulties. To begin with, it is a class party, and the class is not my class. If I am going to pursue sectional interests at all, I shall pursue my own. When it comes to the class struggle as such, my local and personal patriotisms, like those of every one else, except certain unpleasant zealous ones, are attached to my own surroundings. I can be influenced by what seems to me to be justice ad good sense; but the Class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie."

Keynes went on to argue: "But this is not the fundamental difficulty. I am ready to sacrifice my local patriotisms to an important general purpose. What is the real repulsion which keeps me away from Labour? I cannot explain it without beginning to approach my fundamental position. I believe that in the future, more than ever, questions about the economic framework of society will be far and away the most important of political issues. I believe that the right solution will involve intellectual and scientific elements which must be above the heads of the vast mass of more or less illiterate voters. Now, in a democracy, every party alike has to depend on this mass of ill-understanding voters, and no party will attain power unless it can win the confidence of these voters by persuading them in a general way either that it intends to promote their interests or that it intends to gratify their passions... Recently there have been ill-advised movements in the direction of democratising the details of the party programme. This has been a reaction against a weak and divided leadership, for which, in fact, there is no remedy except strong and united leadership. With strong leadership the technique, as distinguished from the main principles, of policy could still be dictated above. The Labour Party, on the other hand, is in a far weaker position. I do not believe that the intellectual elements in the party will ever exercise adequate control." (121)

Keynes added "on the negative test, I incline to believe that the Liberal Party is still the best instrument of future progress - if only it had strong leadership and the right programme." Keynes therefore decided to became an active member of the Liberal Party, lecturing at their summer schools, speaking on behalf of Liberal candidates at elections. On 25th September, 1926, David Lloyd George, invited "14 professors" including Keynes to his home to discuss the political future of the country. Keynes told H. G. Wells: "The occasion was a gathering of a few trying to lay the foundations of a new radicalism; and for the first time for years I felt a political thrill and the chance of something interesting being possible in the political world." (122)

Keynes was asked to head an industrial inquiry into the state of the British economy. Keynes was not very sympathetic to the world of business. "Keynes ranked business life so low partly because he considered that the material good produced by enterpreneurs had less ethical value than the intellectual and aesthetic goods produced by dons and artists, partly because he despised the 'love of money' as a motive for action." Keynes met several businessmen during this investigation and he came to the conclusion that most of them were "stupid and lazy". Keynes became convinced in the idea of the three-generation cycle: "the man of energy and imagination creates the business: the son coasts along; the grandson goes bankrupt." (123)

As he explained in an article written in the previous year: "I believe that the seeds of the intellectual decay of Individualist Capitalism are to be found in an institution which is not in the least characteristic of itself, but which it took over from the social system of Feudalism which preceded it - namely, the hereditary principle. The hereditary principle in the transmission of wealth and the control of business is the reason why the leadership of the Capitalist Cause is weak and stupid. It is too much dominated by third-generation men. Nothing will cause a social institution to decay with more certainty than its attachment to the hereditary principle. It is an illustration of this that by far the oldest of our institutions, the Church, is the one which has always kept itself free from the hereditary taint." (124)

After the article was published Keynes received a letter Laurence Cadbury, the "youngest of the third generation" of the coca firm, who hoped he might allow "a few exceptions to the general rule". (125) In fact, the two men became friends and Cadbury served with Keynes on the Liberal Industrial Inquiry. The only business people Keynes respected were the Liberal Quaker business families - the Frys, Rowntrees and Cadburys - who were known to have enlightened views on industrial management. (126)

Keynes wrote a series of articles attacking the economic policies of the Conservative government led by Stanley Baldwin. This included the decision by Winston Churchill to the return to the gold standard. In an article that appeared in The Nation he argued that going back to gold at the pre-war parity had put two shillings on each ton of coal had had led to a 10% wage reduction. He attacked the coal owners for having no ideas except to reduce wages and extend hours - the latter being "half-witted" in view of the surplus productive capacity in the industry. These proposals showed "that we are dealing with a decadent, third-generation industry". (127)

In a speech he gave to members of the Liberal Party who hoped to become members of parliament, Keynes he criticised the "anti-communist rubbish" of the right and the "anti-capitalist rubbish" of the left. Keynes went on to point out that "methods which were well adapted to continually expanding businesses are ill adapted to stationary or declining ones... Combination in the business world, just as much as in the labour world, is the order of the day; it would be useless as well as foolish to try to combat it. Our task is to take advantage of it, to regulate it, to turn it into the right channels." . (128)

Keynes believed that the government should experiment with "all kinds of new partnerships between the state and private enterprise" to have "a wages and hours policy" and to promote industrial training and labour mobility. However, he rejected the notion of courses for business studies at university. In a radio interview on the BBC he said it would be a mistake for a university to attempt vocational training: "Their business is to develop a man's intelligence and character in such a way that he can pick up relatively quickly the special details of that business he turns to subsequently." (129)

Keynes came under attack from the right-wing of the Liberal Party who saw some of his ideas as being "socialistic". Robert Brand, the fourth son of Henry Brand, 2nd Viscount Hampden, argued against state involvement in industry. He defended profit as a reward for risk and argued that state enterprises would involve the community in vast losses because they were sheltered from the failure which private enterprise visits on the incompetent. "I certainly hold strongly to the opinion that the world is essentially a chancy and risky place, and will always remain so... I would prefer the losses resulting from the risks inherent in almost every sphere of life coming out into the open... rather than being hidden and concealed as they are where public or semi-public corporations can cover them up by a recourse to rates and taxes." (130)

Keynes argued in Britain's Industrial Future (1928) for the "comprehensive socialisation of investment". He proposed that the investment funds of the public concerns, whether borrowed or raised by taxation, should be pooled, and segregated into a capital budget, to be spent under the direction of a national investment board. He also suggested attracting new savings through the issue of national investment bonds for capital development, thus slowly replacing dead-weight debt by productive debt without increasing the outstanding amount of loans. "We have here, with the least possible disturbance, an instrument of great power for the development of the national wealth and the provision of employment. An era of rapid progress in equipping the country with all the material adjuncts of modern civilisation might be inaugurated, which would rival the great Railway Age of the nineteenth century." (131)

Keynes pointed out that "ignorance is the root of the chief political and social evils of the day". Keynes made a plea for an economic general staff to utilise expert knowledge, and the now familiar attack on the hereditary principle. "How can economic science became a true science, capable, perhaps, of benefiting the human lot as much as all the other sciences put together, so long as the economist, unlike other scientists, has to grope for and guess at the relevant data of experience? The nationalising of knowledge is the one case for nationalisation which is overwhelmingly right." (132)

Keynes also controversially argued for a reduction in defence spending: "There is no automatic standard of reasonableness in this connection (the desirable level of defence spending); but we may find comparatively firm ground if we regard our expenditure on defence as an insurance premium incurred to enable us to live our lives in peace and consider what rate of premium we have paid for the privilege in the past. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century we were in no imminent danger of war. Our defence expenditure was £25 millions - a premium of 2 per cent (of national income). In 1913... the premium had jumped to 3½ per cent. Today it is still 3 per cent, though we see no reason for regarding this country as in greater peril than in the last quarter of the nineteenth century." (133)

Laissez-Faire Economics

In 1928, Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, was considered the most important economist in the world. He was the follower of the laissez-faire theory of economics that had first been established by Adam Smith in the 18th century. In his book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) used the metaphor of an "invisible hand" to describe the unintentional effects of economic self-organization from economic self-interest. (134)

Smith developed this concept in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). He argued that: "By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.... It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages." (135)

Fisher's views on laissez-faire economics were very popular in the United States. Prices of these stocks and shares constantly went up and so investors kept them for a short-term period and then sold them at a good profit. As with consumer goods, such as motor cars and washing machines, it was possible to buy stocks and shares on credit. This was called buying on the "margin" and enabled "speculators" to sell off shares at a profit before paying what they owed. In this way it was possible to make a considerable amount of money without a great deal of investment. During the first week of December, 1927, "more shares of stock had changed hands than in any previous week in the whole history of the New York Stock Exchange." (136)

The share price of Montgomery Ward, the mail-order company, went from $132 on 3rd March, 1928, to $466 on 3rd September, 1928. Whereas Union Carbide & Carbon for the same period went from $145 to $413; American Telephone & Telegraph from $77 to $181; Westinghouse Electric Corporation from $91 to $313 and Anaconda Copper from $54 to $162. (137)

John J. Raskob, a senior executive at General Motors, published an article, Everybody Ought to be Rich in August, 1929, where he pointed out: "The common stocks of their country have in the past ten years increased enormously in value because the business of the country has increased. Ten dollars invested ten years ago in the common stock of General Motors would now be worth more than a million and a half dollars. And General Motors is only one of may first-class industrial corporations." He then went on to say: "If a man saves $15 a week, and invests in good common stocks, and allows the dividends and rights to accumulate, at the end of twenty years he will have at least $80,000 and an income from investments of around $400 a month. He will be rich. And because income can do that, I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich, but ought to be rich." (138)

1929 General Election

In 1928 Britain had over a million people out of work. Some members of the Labour Party thought that they needed to promise dramatic reform in the next election and favoured the reforms being suggested by Keynes. Richard Tawney sent a letter to the leaders of the party: "If the Labour Election Programme is to be of any use it must have something concrete and definite about unemployment... What is required is a definite statement that (a) Labour Government will initiate productive work on a larger scale, and will raise a loan for the purpose. (b) That it will maintain from national funds all men not absorbed in such work." MacDonald refused to be persuaded by Tawney's ideas and rejected the idea that unemployment could be cured by public works. (139)

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) argued for a policy that became known as "Socialism in Our Time". The main aspect of this policy was what became known as the "Living Wage". The ILP argued that the provision of a minimum living income for every citizen should be the first and immediate objective. It called for the "legal enforcement of a national minimum wage adequate to meet all needs in all public services and by all employers working on public contracts, supplemented by machinery for the legal enforcement of rising minima on industry as a whole, as well as by expanded social services financed out of taxation on the bigger incomes, and by a nationally financed system of Family Allowances." MacDonald described the measure as "flashy futilities". (140)

David Lloyd George, the leader of the Liberal Party, also agreed with Keynes. On 27th March 1928, he made a speech where he declared: "Let us be up and doing, using our idle resources to increase our wealth. With men and plant unemployed, it is ridiculous to say that we cannot afford new developments. It is precisely with these plants and these men that we shall afford them. When every man and every factory is busy, then will be the time to say that we can afford nothing further." (141) The following month Keynes said, "We have the savings, the men and the material. The things are worth doing. It is the very pathology of thought to declare that we cannot afford them." (142)

In January 1929, 1,433,000 people in Britain were out of work. Stanley Baldwin was urged to take measures that would protect the depressed iron and steel industry. Baldwin ruled this out owing to the pledge against protection which had been made at the 1924 election. Agriculture was in an even worse condition, and here again the government could offer little assistance without reopening the dangerous tariff issue. Baldwin was considered to be a popular prime minister and he fully expected to win the general election that was to take place on 30th May. (143)

In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (144)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (145)

During the election campaign, David Lloyd George published a pamphlet, We Can Conquer Unemployment. Lloyd George pledged that if his party were returned to office, they would reduce levels of unemployment to normal within one year by utilising the stagnant labour force in vast schemes of national development. Lloyd George proposed a government scheme where 350,000 men were to be employed on road-building, 60,000 on housing, 60,000 on telephone development and 62,000 on electrical development. The cost would be £250 million, but the cumulative effect of all schemes would generate an annual saving of £30 million to the Unemployment Fund. (146)

Lloyd George was attacked by Tory politicians as they feared the proposals would appeal to the public. Neville Chamberlain, the Conservative MP for Ladywood argued that it cost £250 a year to find work for one man and only £60 to keep him in idleness. The government published a White Paper that "would reduce unemployment without bankrupting the nation". Baldwin suggested that "he (Lloyd George) has spent his whole life in platering together the true and the false and therefore manufacturing the plausible". William Joynson-Hicks, the Home Secretary, said he could not "understand how a man of Lloyd George's ability could put such a proposal before the people of this country". (147)

John Maynard Keynes and Hubert Henderson, who had helped Lloyd George to write the pamphlet, replied with another pamphlet, Can Lloyd George Do It? They concluded that it was possible for a government to successively introduce these methods to reduce unemployment. They then went on to satirise Baldwin's approach to the subject: "You must not do anything for that will only mean that you cannot do something else... We will not promise more than we can perform. We therefore promise nothing." (148)