Society of Friends (Quakers): 1643-1694

On 8th September 1643, George Fox shared a jug of beer with a cousin and his friend. After drinking the first pint, the other two decided to see who could drink the most and pledged that the one stopping first had to pay for all the beer consumed. He was amazed that a cousin who shared his own approach to religion could take part in a drinking contest. Fox paid for the whole jug of beer and announced that he would leave rather than have anything to do with this activity: "If it be so. I'll leave you." (1)

The following day Fox broke off his apprenticeship, left home, and went to London, stopping in towns on the way where the Parliamentary Army were garrisoned. At the time the country was in the second year of the English Civil War. Although he sympathised with Parliament over its dispute with King Charles I, Fox refused to take part in the fighting. However, he did take part in the discussions on religion with the soldiers. According to his biographer, H. Larry Ingle, Fox was supportive of the ideas put forward by John Wycliffe and the Lollards more than 250 years earlier. (2)

Wycliffe tried to employ the Christian vision of justice to achieve social change: "It was through the teachings of Christ that men sought to change society, very often against the official priests and bishops in their wealth and pride, and the coercive powers of the Church itself." (3) Barbara Tuchman has claimed that John Wycliffe was the first "modern man". She goes on to argue: "Seen through the telescope of history, he (Wycliffe) was the most significant Englishman of his time." (4)

Fox reached Chipping Barnet on the outskirts of London in June 1644. Approaching his twentieth birthday, Fox wrote in his journal that he was beset by "a temptation to despair". (5) He did not explain what this "temptation" was but it has been suggested that it was sexual desire: "The lure of sexual adventure, in the distant place, in time of war when moral standards tend to decline anyway, and with a willing partner, may well have been the sinful snare that so depressed Fox." (6)

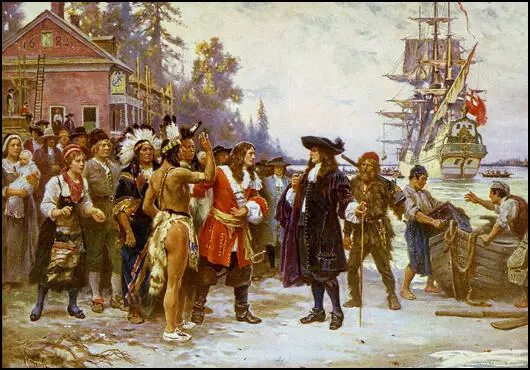

Fox then moved on to London. At that time the population of the city was about a third of a million, more than 6 per cent of the country's total population. (7) Fox was impressed by some features of the city but appalled by other aspects: "The cheap plays and six-penny whores he would have eschewed on moral grounds, although he might have found diversions in seeing a bear-baiting down at the river or the occasional Indian brought back from the colonies across the Atlantic and put on display." (8)

Religious Dissenters

London was also a hotbed of religious ideas. John Lilburne and the Levellers who were active in the New Model Army, were unhappy with the way that the war was being fought. Whereas they hoped the conflict would lead to political change, this was not true of most of the Parliamentary leaders. "The generals themselves members of the titled nobility, were ardently seeking a compromise with the King. They wavered in their prosecution of the war because they feared that a shattering victory over the King would create an irreparable breach in the old order of things that would ultimately be fatal to their own position." (9)

Lilburne's political activities were reported to Parliament. As a result, he was brought before the Committee of Examinations on 17th May, 1645, and warned about his future behaviour. William Prynne and other leading Presbyterians, such as John Bastwick, were concerned by Lilburne's radicalism. They joined a plot with Denzil Holles against Lilburne. He was arrested and charged with uttering slander against William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons. (10)

Supported by income from his shoemaking skills, Fox wandered into Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. There his anti-clericalism, coinciding with social and political upheaval in the aftermath of the civil war, attracted followers. Fox argued there was no need to rely on human teachers, "Fox preached, for even the scriptures were less authoritative than one's inward guide. He relied on the Bible, which he knew well and whose words were prominent in his teaching and writing, but his stress on the primacy of the Spirit inevitably fed the kind of individualism that greatly hindered lasting unity among his diverse followers. Because the scriptures did not use the term and spoke nothing of it explicitly, he rejected the doctrine of the Trinity, a position bound to alarm and antagonize the orthodox. Nor did he make clear distinctions between the Father and the Son.... He could also find no scriptural justification for paying tithes to a church with which he disagreed, let alone to a private person who might be thus enriched... This cluster of beliefs put Fox beyond the pale of mainstream puritanism. Most of these ideas did occur in the thinking of other contemporary radical sectaries and he was not the first to make a principle of the non-payment of tithes, but he did place this stance more centrally within his teaching than other radicals did." (11)

Fox often preached to members of the New Model Army. So did members of other radical groups such as the Anabaptists and Ranters. This created concern for the Presbyterians and one of its ministers, Richard Baxter, an army chaplain during the war commented: "If they pulled down the parliament, imprisoned the godly, faithful members, and killed the king... if they sought to take down tithes and parish ministers, to the utter confusion of religion in the land, in all these the Anabaptists followed them." (12)

According to Pauline Gregg it was not until 1647 that he came to the simple realization that the spirit of God was within each man, and that the knowledge of Christ was an inner light that could reveal itself at any time without the help of dogma, form, or ceremony. "A man need be equipped with nothing but a humble spirit and a belief in God and Jesus Christ. No prayer-book, no preacher, no sacrament, no church, who needed to guide him - only the witness in his conscience."(13)

Elizabeth Hooton was one of the first people to be "convinced" by Fox after hearing him speak in Nottingham in 1647. Her husband, Oliver Hooten, a prosperous farmer, seems to have opposed his wife's new beliefs "in so much that they had like to have parted". Gerard Croese, a 17th century historian suggested that she "was the first of her sex among the Quakers who attempted to imitate men, and preach" and suggested that she was a role model for women: "after her example, many of her sex had the confidence to undertake the same office". (14) She travelled the country and was arrested and imprisoned several times over the next few years. (15)

Quakerism

On 30th October, 1650, Fox interrupted a church service in Derby. He was arrested and after eight hours of close questioning he was sent to jail for a term of six months for blaspheming. Jails in the 17th century were extremely unpleasant. Jailers charged prisoners fees for better accommodations and food. Jailers were not subject to rules and treated people like Fox who did not share their religious views, very badly. Derby jail was sited over a branch of the River Derwent, exposing its prisoners to damp and filth. (16)

During this period George Fox called his followers "Children of the Light", "People of God", "Royal Seed of God" or "Friends of the Truth". However, one of his critics, Gervase Bennett, described Fox and his followers as "Quakers". This was a derisive term and was based on the fact that Fox's followers quaked and trembled during their worship. Fox defended his followers by pointing out that there were numerous biblical figures who were said to have also trembled before the Lord. Later they became known as the "Religious Society of Friends". (17)

It has been argued by Pink Dandelion, the author of The Quakers (2008) that the Quakers experience of war led them to adopt a pacifist approach and to see war and fighting as carnal. When George Fox was held in Derby Jail in 1650 he was offered a captaincy in the army in exchange for the freedom but he declined, claiming he fought with spiritual weapons not outward ones. (18)

Fox refused to bow or to take off his hat to anyone, to use the pronouns "Thee" and "Thou" to all men and women whether they were rich or poor, never to call the days of the week or the months of the year by their names but only by their numbers. He would enter church services and denounce the preacher in the midst of his sermon. Fox attempted to teach the conviction of moral perfection and "almost a personal infallibility, of spirit-inspired utterance". (19) In one pamphlet Fox stated: "Did not the Whore of Rome give you the name of vicars... and parsons and curates?" They "set up your schools and colleges... whereby you are made ministers?" (20)

In 1651 Fox met James Nayler at Woodchurch. Nayler had been a preacher attached to the parliamentary army during the English Civil War. An officer in the New Model Army recalled: "I found it was James Nayler preaching to the people, but with such power and reaching energy as I had not till then been witness of… I was struck with more terror before the preaching of James Nayler than I was before the battle of Dunbar, when we had nothing else to expect but to fall a prey to the swords of our enemies." (21)

According to Nayler's biographer, Leo Damrosch, "there is no evidence to support Fox's later suggestion that this meeting was the cause of Nayler's conversion... Certainly radical religious ideas had been widely discussed in the New Model Army, and it may be more than coincidental that Anthony Nutter, whom Fox's family had known in Leicestershire, was the minister at West Ardsley when Nayler was growing up." (22)

Fox knew how to tailor his message to address the problems of his audience. For example, his attacks on the payment of tithes was extremely popular. (23) The Quakers believed that individuals of either sex could receive the same prophetic inspiration that the biblical writers had and, guided by the inner light, could express this with full authority. (24) Nayler wrote: "The true ministry is the gift of Jesus Christ, and needs no addition of human help and learning… and therefore he chouse herdsmen, fishermen, and plowmen, and such like; and he gave them an immediate call, without the leave of man". (25) He argued that he himself had been a ploughman, and that when the apostles proclaimed the gospel "they were counted fools and madmen by the learned generation". (26)

Margaret Fell

In late June 1652, George Fox interrupted a service at a church in Ulverston. His words had an impact on Margaret Fell, who was in the congregation. She gave him refuge and by the time he left Swarthmoor Hall he had converted Margaret and her daughters, and most of her household to Quakerism. (27) Margaret's husband, Judge Thomas Fell who was MP for Lancaster and a close ally of Oliver Cromwell, was in London at the time. Margaret was unsure of what her absent husband's reaction would be to these happenings, was, as she put it, "stricken with such sadness that I knew not what to do." (28)

As Bonnelyn Young Kunze has pointed out: "Upon his return Judge Fell was troubled by his wife's sudden conversion to this new dissenting sect, but Margaret convinced her husband of her new-found faith and introduced Fox to him. After her conversion to Quakerism she ceased to attend St Mary's, Ulverston, although her husband continued to attend regularly without her, and never converted to the sect. However, his sympathy towards Quakers was important, especially given his judicial position, and he allowed the Friends to hold their meetings at Swarthmoor Hall free from persecution." (29)

Margaret Fell was one of the most important converts to Quakerism. Her name and connections, practical organizational abilities and energies, as well as her husband's influence, were all assets Fell brought to the movement. Before her conversion, Fox had had only modest success. Now, as he travelled around Cumbria he began to obtain more and more followers. Fox wrote in his journal that "there is arising a new and living way out of the north". (30)

Fox would often interrupt religious services and accused ministers of being "hireling priests" and demanded abolition of the benefices and tithes that supported them. It was a fixed Quaker principle to accept no payment for preaching and to address any who might listen, often speaking in the open air, rather than to form settled congregations. When ministers complained that unauthorized preachers were invading their territory, Nayler replied, 'It is true, our habitation is with the Lord, and our country is not of this world". (31) Some three dozen Lancashire ministers appeared at Lancaster quarter sessions to lodge a complaint against Fox and Nayler, but Judge Fell interceded on their behalf and they were released. (32)

Growth of Quakerism

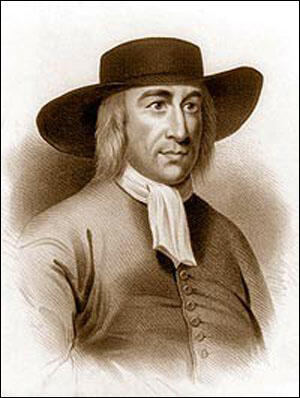

George Fox became the leader of a group that included Margaret Fell, Elizabeth Hooton, William Penn, James Nayler, Edward Burrough, Francis Howgill, Isaac Penington, John Perrot, Thomas Salthouse, Martha Simmonds, Anne Docwra, Anne Newby, Mary Fisher, Ann Austin, John Audland, Samuel Fisher, Alexander Parker, Robert Rich, Richard Farnworth, Richard Hubberthorne, Thomas Ellwood, Alexander Parker, George Whitehead, William Dewsbury and Thomas Goodaire. They usually travelled the country in pairs. Quakers believed strongly in the wearing of plain clothes. The uniform of the broad-rimmed hat or bonnet all in Quaker grey became associated with Quakerism. (33)

Fox attacked the frivolities of traditional village life - gambling, cock-fighting, wrestling, dancing, football and bull-baiting. (34) This attitude towards "sinful pastimes" drove a wedge between Fox and his followers and the people "who sought by such means to introduce excitement into the hard work and tedium of daily existence". Fox's stern attitude differed little from the more mainstream Presbyterian and Independent ministers. (35)

Fox was also critical of the rich and powerful. In 1653 he claimed: "O ye great men and rich men of the earth! Weep and howl for your misery that is coming... The fire is kindled, the day of the Lord is appearing, a day of howling... All the loftiness of men must be laid low." This upset the local gentry but they enjoyed the protection of the military authorities, and of the occasional local gentleman of radical inclinations. They also had considerable support from the rank and file in the army. (36)

At first Quaker meetings were in people's homes, barns or by the roadside. The Quakers built "Meeting Houses" only when their own homes became too small. Given the idea of spiritual equality, anyone could speak when prompted by God. Prayer involved the speaker kneeling and everyone else standing and removing their hats, the only time Quakers did so. "Quakers also performed signs, such as 'going naked', as part of their public witness to the new covenant they had established with God and the apostasy of the old ways of believing." (37)

Francis Higginson claimed that Quaker meetings attracted up to two hundred people. Instead of singing or reading the Bible or administering sacraments, the faithful would sit, sometimes for nearly three hours, in silence, until someone presumed to speak under the inspiration of the spirit. Higginson said that the speaker would have the attention of the whole group because "they believe them to be the very words and dictates of Christ." While the speaking continued, some, especially women and children, would fall into quaking fits. Higginson quoted Fox as saying: "Let them alone, trouble them not... the spirit is now struggling with the flesh." (38)

In 1653 Fox was arrested in Carlisle after he said he considered himself God's son, that he had seen God's face, and that God was the original word and that the Scriptures were mere human writings. He was accused of blasphemy and heresy and remanded in the city dungeon. He was beaten with a cudgel by his jailer after he refused to buy the food his keepers sold. He was released after Margaret Fell wrote a letter for general circulation attacking those in government who professed to favour reformation and liberty of conscience while imprisoning people like Fox. (39)

Fox always insisted that God called women to be preachers and evangelists just as he had traditionally called men. It has been estimated that ministry of women, made up 45% of the early Quaker movement. (40) Margaret Fell and Elizabeth Hooton, became two of the Quakers most respected leaders. These women also raised important questions about overturning other traditional relationship between the sexes. Men began to argue that women preachers would lead to immorality. One critic complained that even conversing with women seduced and drew them away from their husbands. One observer claimed that the Quakers "hold a community of women and other men's wives and practice living upon one another too much." (41)

Edward Burrough became one of the most important figures in the movement. In 1654 he announced that "the fire is to be kindled... and the proud and all that do wickedly shall be as stubble... The sword of the Lord is put into the hands of them which is hated and despised by the rulers and officers, which is scornfully called Quakers but they shall conquer by the sword of the Lord." (42) Burrough put forward arguments similar to the Levellers. He denounced all "earthly lordship and tyranny and oppression... by which creatures have been exalted and set up one above another, trampling under foot and despising the poor." Burrough admitted that the Quaker preacher is considered "a sower of sedition, or a subverter of the laws, a turner of the world upside down, a pestilent fellow". (43)

George Fox and James Nayler wrote several pamphlets explaining Quakerism and they began to be sold in London bookstalls. Oliver Cromwell became increasingly concerned about this new religious movement and in February 1655 he issued a proclamation making it illegal to interrupt Christian ministers or assemblies. (44) A few days later Fox was arrested and charged with this offence and an armed escort marched him off the hundred miles to the capital. On his arrival Cromwell demanded Fox's assurance that he would not take up arms against his government. (45)

Fox published a statement on 5 March, 1655. Fox wrote "I do deny the carrying or drawing of any carnal sword against any or against you Oliver Cromwell." He also claimed that while he was personally opposed to participating in war, he recognized and accepted the authority of the state to use the sword. "The magistrate," he said, "bears not the sword in vain." Fox rejected "wicked inventions of men and murderous plots," not because he opposed the ends they sought as much as the means they used. (46)

Fox was not a pacifist in the modern sense that he utterly rejected participating in all wars and violent conflicts. On 9 March, 1655, Cromwell ordered the jailers to bring Fox to the Whitehall Palace. Cromwell complained that the Quakers were always quarreling with ministers. Fox replied by blaming the priests for refusing to accept the truth, preaching for "filthy lucre," and being "covetous and greedy like the dumb dogs." Cromwell ordered his release as long as he avoided any violation of Cromwell's proclamation against invading churches and interrupting their ministers. (47)

There were some Quakers who were pacifists. This included Agnes Wilkinson who made an unequivocal pacifist demand that was addressed "to all who wear swords". She advised "all who handle a sword and take up carnal weapons... to strip yourself naked of all your carnal weapons and take unto you the sword of the Spirit, for the Lord is coming to judge men." (48)

To prepare the way for the missionaries, Fox penned a letter to Pope Alexander VII and the rulers of all countries, including the kings of Spain and France, both staunch Catholics. Fox expressed the hope that his followers would not be persecuted and warned that God would judge the crowned heads by how they treated the expeditionary force: "Be swift to hear and slow to speak and slower to persecute," for the Lord's "fire is going forth to burn up the wicked, which will leave neither root nor branch." (49)

Quakers continued to gain new members. This included John Lilburne, the former leader of the Levellers. In October, 1655, he was moved to Dover Castle. While he was in prison Lilburne continued writing pamphlets including one that explained why he had joined the Quakers. "I wish to make a public declaration in print, of my real owning, and now living in the life and power of those divine and heavenly principles, professed by those spiritualized people called Quakers." (50)

Other former Levellers joined the group. Especially after they began to call for annual Parliaments. One pamphlet said that Quakers "teach the doctrine of levelling privately to their disciples". The leaders were accused of being "downright Levellers", only concealing their views from fear of suppression. It was claimed that this was the reason why rich people were not Quakers. A member of the House of Commons described Quakers as "all Levellers, against magistracy and property". (51)

Bertrand Russell has argued in The History of Western Philosophy (1946) that there is a lot to admire in Quakerism: "If you follow Christ's teaching, you will say 'Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.' I have known Quakers who could have said this sincerely and profoundly, and whom I admired because they could. But before giving admiration one must be very sure that the misfortune is felt as deeply as it should be... The Christian principle, 'Love your enemies,' is good... but the Christian principle does not inculcate calm, but an ardent love even towards the worst of men. There is nothing to be said against it except that it is too difficult for most of us to practise sincerely." (52)

James Nayler

James Nayler arrived in London in July 1655. As soon as he appeared in what he termed "this great and wicked city where abomination is set" he began attracting large numbers to his meetings. He found Baptists and soldiers especially responsive to his message. Nayler was an accomplished speaker and writer, as well as a creative thinker. William Dewsbury, who had the opportunity to watch both Fox and Nayler when they visited Northampton, marveled at the way Nayler "confounded the deceit" of the audience and thought he was a greater speaker than Fox. (53)

Christopher Hill has argued that many people in the movement regarded Nayler as the "chief leader" and the "head Quaker in England". (54) Colonel Thomas Cooper pointed out in the House of Commons: "He (Nayler) writes all their books. Cut off this fellow and you will destroy the sect." (55) Even one of his critics, John Deacon, conceded that he was "a man of exceeding quick wit and sharp apprehension, enriched with that commendable gift of good oratory with a very delightful melody in his utterance." (56)

According to H. Larry Ingle: "Some people, Friends as well as outsiders, looked on Fox as a bit 'strange' - a word used by a close observer and companion - and wondered at the way other Quakers tended to be quiet in his presence and defer to him during meetings. In personal debate Nayler was quick and intelligent. His writings were incisive and polished, whereas Fox in his writings tended to plod and stumble. if not as charismatic, Nayler still attracted a bevy of followers of an intense type, people who practically worshiped him as the harbinger of a new age. They were willing to follow him anywhere and to do practically anything to demonstrate their commitment. Some of the most vocal of these acolytes were women, and this fact led detractors, then and later, to see an insidious influence at work: either he had some mysterious hold over these women or they themselves were temptress using their wiles to turn his head." (57)

No written rules governed the Society of Friends because it was a kind of community of equals, all committed to the same goals and having the interests of the group at heart. The question of leadership was left open. Fox and Nayler had been involved in the movement together almost from the beginning and shared many days and nights of travelling, and co-authored pamphlets and epistles. However, by 1655 Fox came infrequently to London, preferring to continue his travels in the countryside, and some regarded Nayler as the movement's leader. This was especially true of Martha Simmonds, "an intelligent and independent person, author of several moving pamphlets about spiritual seeking and apocalyptic hopes." (58)

Fox became concerned about how Nayler was winning such a fervent band of disciples in London. It seemed to Fox that Nayler was erecting a base of influence that gave him a strength and a prestige independent of Fox. In the meetings he held he began talking about "wicked mountains and parties crying against him". With the ability to win followers, "Nayler posed a threat of major proportions to Fox. No movement can follow two masters, as Fox realized." (59)

Oliver Cromwell was also becoming concerned about the popularity of Nayler. As Christopher Hill pointed out: "Nayler was a leader of an organized movement which, from its base in the North, had swept with frightening rapidity over the southern counties. It was a movement whose aims were obscure, but which certainly took over many of the aims of the Levellers, and was recruiting former Levellers and Ranters... M.P.s were anxious to finish once and for all with the policy of religious toleration which, in their view, had been the bane of England for a decade. The government of the Protectorate, satisfactorily conservative in many ways, was still in their view woefully unsound in this respect. The fact that its relative tolerance resulted from its dependence on the Army only heightened the offence." (60)

In January 1656, Fox was imprisoned in Launceston. Martha Simmonds travelled to Launceston to meet with Fox, and to state her view that Nayler was the leader of the movement. Fox wrote to Nayler an indignant letter reporting that "she (Simmonds) came singing in my face, inventing words" and informing him that his heart was rotten. In September 1656, Fox was released from prison and proceeded to Exeter, where he demanded that Nayler acknowledge subservience, and when Nayler refused to kiss his hand told him insultingly to kiss his foot instead. (61) They parted bitterly, and later Fox remembered this episode as a critical threat to the movement: "So that after I had been warring with the world, now there was a wicked spirit risen up amongst Friends to war against". (62)

In October 1656, Nayler re-enacted the Palm Sunday arrival of Christ in Jerusalem. Seated on an ass he was escorted into Bristol by women strewing branches in his path. Oliver Cromwell and other members of the House of Commons were horrified by Nayler allowing himself to be hailed by devoted disciples as a new Messiah. Nayler was arrested. Philip Skippon, a staunch presbyterian and the major-general in charge of the London area, complained that Cromwell's policy of toleration had fostered a Quaker threat: "Their great growth and increase is too notorious, both in England and Ireland; their principles strike at both ministry and magistracy. Many opinions are in this nation (all contrary to the government) which would join in one to destroy you, if it should please God to deliver the sword into their hands." (63)

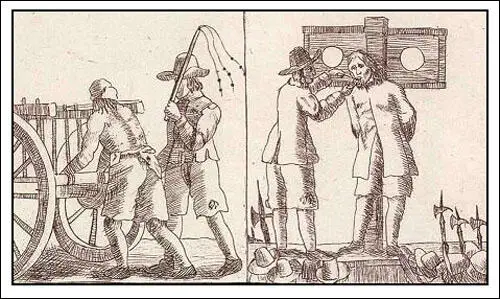

At his trial before Parliament, Nayler declared that he had enacted a "sign" without mistaking himself for Christ. A few members were prepared to accept his account, but the majority were determined on punishment and disagreed only as to its extent. By the narrow margin of 96 to 82, a motion to put him to death was defeated, and after further debate it was resolved on 16 December that Nayler be whipped through the streets by the hangman, exposed in the pillory, have his tongue bored through with a red-hot iron, and have the letter B (for blasphemy) branded on his forehead. He was then to be returned to Bristol and compelled to repeat his ride in reverse while facing the rear of his horse, and finally he was to be committed to solitary confinement in Bridewell Prison for an indefinite period. (64)

Nayler's punishment was carried out in every detail, including 300 lashes that tore all the skin off his back, and the concluding scene at the pillory was witnessed by a large crowd that included Thomas Burton, the MP for Westmorland. He approved of the punishment but admired Nayler's stoicism: "He put out his tongue very willingly, but shrinked a little when the iron came upon his forehead. He was pale when he came out of the pillory, but high-coloured after tongue-boring… Nayler embraced his executioner, and behaved himself very handsomely and patiently." (65)

Christopher Hill has argued that Oliver Cromwell used the Nayler incident to suppress the Quakers: "So conservatives in Parliament seized the occasion to put the whole Quaker movement in the dock, and the government's religious policy too. The hysteria of M.P.s' contributions to the debate shows how frightened they had been, how delighted they were to seize the opportunity for counterattacked. And the conservatives won their showdown with the government. Nayler was tortured, to discourage the others. Cromwell queried the authority for Parliament's action against Nayler, but ultimately he made political use of the Nayler case to manoeuvre the Army into accepting Parliament's Petition and Advice, a constitution which established something like the traditional monarchy and state church, and drastically limited the area of religious toleration." (66)

Fox refused to sign a petition asking that Nayler's punishment be remitted. Fox also endorsed Parliament's actions against Nayler: "If the seed of the serpent speaks and says he is Christ that is the liar and the blasphemy and the ground of all blasphemy." It has been pointed out that Nayler had been convicted for something that Fox had done, claimed to be the "Son of God".Alexander Parker argued that by alienating the Naylerites, Fox was weakening the movement. Robert Rich, a successful merchant and shipowner from London, was criticised by Fox for his support and continued public defense of the jailed Quaker. (67)

Fox believed that Nayler had been attracting the following of the Ranters. This was supported by Thomas Collier who wrote in 1657 that "any that know the principles of the Ranters" may easily recognize that Quaker doctrines are identical. Both would have "no Christ but within; no Scripture to be a rule; no ordinances, no law but their lusts, no heaven nor glory but here, no sin but what men fancied to be so, no condemnation for sin but in the consciences of ignorant ones". Only Quakers "smooth it over with an outward austere carriage before men, but within are full of filthiness". (68)

Edward Burrough, who had earlier been associated with the Ranters distanced himself from the movement that its leading figures, Abiezer Coppe and Laurence Clarkson advocated "free love". (69) Coppe asserted that property was theft and pride worse than adultery: "I can kiss and hug ladies and love my neighbour's wife as myself without sin." (70) Peter Ackroyd claimed that Coppe and Clarkson professed that "sin had its conception only in imagination" and told their followers that they "might swear, drink, smoke and have sex with impunity". (71) One slogan used by the Ranters included: "There's no heaven but women, nor no hell save marriage." (72) Burrough claimed that the Ranters "have scorned self-righteousness"; their house had once been the house of prayer, though now it has become "the den of robbers", cultivating false peace, false liberty and love and fleshly joy. (73)

Fox's conflict with Nayler highlighted the disruptive side to the individualistic faith of the Quakers. Fox realised he would need to find a way to impose discipline. On the question of individualism versus authority, Fox came down on the side of authority. "A two-level system was erected, a meeting at a local level, a larger and more distant one a rung higher, forming a systematic check on a potential dissident's outward expression of inward leadings as determined by those gripping the instruments of power." (74)

It has been argued that: "The Quaker consensus came down on the side of discipline, organization, common sense. The eccentricities of Quakerism were quietly dropped.. Going naked for a sign, miracles and the other individualist exuberances of early Quakers and Ranters disappeared as the inner light adapted itself to the standards of this commercial world where yea and nay helped one to prosper. It is pointless to condemn this as a sell-out as to praise its realism: it was simply the consequence of the organized survival of a group which had failed to turn the world upside down." (75)

Fox's attempt to distance himself from Nayler's "extremism" did not work. Oliver Cromwell decided to remove Quakers from the army and from their positions as justices of the peace. (76) Fox now instructed Quakers all over the country to record their sufferings if they were arrested for attending meetings or for refusing to pay their tithes and not swearing oaths. He directed that "a true and a plain copy of such suffering be sent to London" to demonstrate to Cromwell and the House of Commons the extent of the persecution they had ordered. (77)

James Nayler was released from prison in 1659. He was highly critical of Cromwell's government. He published a pamphlet calling on the Long Parliament to "set free the oppressed people". Nayler explained that Quakers were disappointed by Cromwell's promises of reform. "The simple-hearted" supporters of Parliament, who had been drawn in by "fair pretences" were beginning "to leave you and return home, all men disappointed of their expectation". (78)

Isaac Penington

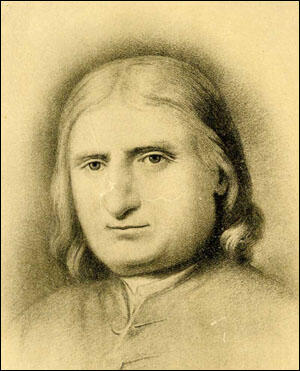

Penington joined the Quakers in May 1658 after hearing George Fox speak in Bedfordshire. In his first Quaker publication, The Way of Life and Death (1658), Penington outlined his view of church history, according to which "the true state of Christianity" had been lost. "The Lord hath been kind to me in breaking of me in my religion, and in visiting me with sweet and precious light from his own spirit; but I knew it not. I felt, and could not but acknowledge, a power upon me, and might have known what it was by its purifying of my heart, and begetting me into the image of God; but I confined it to appear in a way of demonstration to my reason and earthly wisdom, and for want of satisfaction therein, denied and rebelled against it; and so, after all my former misery, lost my entrance, and sowed seeds of new misery and sorrow to my own soul, which since I have reaped." (79)

Penington asked where were the praying people over whom a heathen spirit had descended? (80) Distinguishing between human and divine faith he insisted that one must be guided by the light in one's soul, love simplicity, and live humbly to experience true religion. (81) Penington believed that those who ignore the inner light are like the ancient Jews, for they commit the same errors, reject the doctrine of the new birth, and oppose Quakers as the Jews rejected Christ. (82)

Penington was one of the first to argue that Oliver Cromwell government had betrayed the revolution or what he called "The Good Old Cause". This was a reference to the demands made by Levellers such as John Lilburne, Richard Overton and William Walwyn for political reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (83)

On 18 May 1659 Penington wrote To the Parliament, the Army, and All the Well-Affected, accusing them of betraying the "Good Old Cause" because they committed blasphemy, overthrew God's work, and failed to relieve the poor: "That there hath been a backsliding and turning aside from the Good Old Cause even by the army (who formerly were glorious Instruments in the hand of God) hath been lately confessed, and that they have cause, and desire to take shame to themselves. Now that they may see the cause of shame that lies upon them, and may abase themselves in the sight of God, and before all the world, it behooves them to search narrowly into their backslidings, and consider the fruits thereof, that they may be truly humbled, and turned from that Spirit which led them aside, lest any of them take advantage to make a feigned confession for their own ends, and fall afresh to seek themselves; and their own Interests, and not the Good Old Cause, singly, and nakedly, as in the sight of the Lord." (84)

The Restoration

In 1658 Oliver Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard Cromwell, to replace him as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. The English army was unhappy with this decision. While they respected Oliver as a skillful military commander, Richard was just a country farmer. To help him Cromwell brought him onto the Council to familiarize him with affairs of state. (85)

Oliver Cromwell was in poor health. He had bladder trouble, he was wracked by gout and a boil on his neck caused him a lot of pain. George Fox met him by chance near Hampton Court and found him much changed. The Lord Protector was heard praying for Puritanism and the Protestant Cause and at four o'clock in the afternoon on Friday 3 September 1658, he died. (86)

Oliver Cromwell died on 3rd September 1658. Richard Cromwell became Lord Protector but he was bullied by conservative MPs into support measures to restrict religious toleration and the army's freedom to indulge in political activity. The army responded by forcing Richard to dissolve Parliament on 21st April, 1659. The following month he agreed to retire from government. (87)

Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monk, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army to London. According to Hyman Fagan: "Faced with a threatened revolt, the upper classes decided to restore the monarchy which, they thought, would bring stability to the country. The army again intervened in politics, but this time it opposed the Commonwealth". (88)

Monck reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. Monck now contacted Charles, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles II also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an 'absolute' monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s. (89)

Despite this agreement a special court was appointed and in October 1660 those Regicides who were still alive and living in Britain were brought to trial. Ten were found guilty and were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. This included Thomas Harrison, John Jones, John Carew and Hugh Peters. Others executed included Adrian Scroope, Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Francis Hacker, Daniel Axtel and John Cook. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (90)

Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, Thomas Pride and John Bradshaw were all posthumously tried for high treason. They were found guilty and on the twelfth anniversary of the regicide, on 30th January 1661, their bodies were disinterred and hung from the gallows at Tyburn. (91) Cromwell's body was put into a lime-pit below the gallows and the head, impaled on a spike, was exposed at the south end of Westminster Hall for nearly twenty years. (92)

Mary Dyer: Quaker Martyr

Mary Dyer became a Quaker after meeting George Fox. In 1657 Dyer travelled to North America and settled in Boston. Of all the New England colonies, Massachusetts was the most active in persecuting the Quakers. When the first Quakers arrived in Boston in 1656 there were no laws yet enacted against them, but this quickly changed, and punishments were meted out with or without the law. The Reverend John Norton of the Boston church, clamored for the law of banishment upon pain of death. The punishments imposed on Quakers included the stocks and pillory, lashes with knotted whip, fines, imprisonment, mutilation (having ears cut off), banishment and death. When whipped, women were stripped to the waist, thus being publicly exposed, and whipped until bleeding. (93)

As soon as Dyer arrived in Boston she was immediately recognised and imprisoned. Dyer's husband had to come to get her out of jail, and he was bound and sworn not to allow her to lodge in any Massachusetts town. (94) Dyer continued to travel in New England to preach her Quaker message, and in early 1658 was arrested in the New Haven Colony, and then expelled for preaching that women and men stood on equal ground in church worship and organization. Anti-Quaker laws had been enacted there, and after Dyer was arrested, she was "set on a horse", and forced to leave. (95)

In June 1658 three Quaker activists, Christopher Holder, John Copeland and John Rous arrived in Boston. They were all arrested and sentenced to having their right ears cut off. Dyer was furious when she heard the news and along with the London merchant William Robinson and a Yorkshire farmer named Marmaduke Stephenson, decided to go to Boston to protest these acts of cruelty. The three were arrested and banished, but Robinson and Stephenson returned and were again imprisoned. Mary Dyer went back to protest at their treatment, and was also imprisoned. (96)

On 19 October 1659, Dyer, Robinson and Stephenson were brought before John Endicott, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (97) Endicott explained to them: "We have made many laws and endeavored in several ways to keep you from among us, but neither whipping nor imprisonment, nor cutting off ears, nor banishment upon pain of death will keep you from among us. We desire not your death." Having met his obligation to present the position of the colony's authorities, he sentenced them to death. Endicott told her, "Mary Dyer, you shall go from hence to the place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of execution, and there be hanged till you be dead." She replied, "The will of the Lord be done." When Endicott directed the marshall to take her away, she said, "Yea, and joyfully I go." (98)

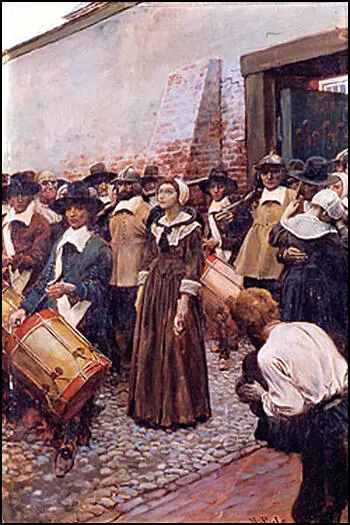

The date set for the executions of Dyer, Robinson and Stephenson was 27 October 1659. (99) Armed soldiers escorted the prisoners to the place of execution. Dyer walked hand-in-hand with the two men. When she was asked about this inappropriate closeness, she responded instead to her sense of the event: "It is an hour of the greatest joy I can enjoy in this world. No eye can see, no ear can hear, no tongue can speak, no heart can understand the sweet incomes and refreshings of the spirit of the Lord which now I enjoy." (100)

Dyer watched Robinson and Stephenson being executed. Her arms and legs were bound and her face was covered with a handkerchief. As she waited to climb the ladder an order of a reprieve was announced. A petition from her son, William, had given the authorities an excuse to avoid her execution. Dyer spent the winter in Rhode Island but, in May 1660, returned once again to Boston. (101) In a letter explaining her actions, she protested against the "unrighteous laws", taking on the mantle of prophet and religious martyr and condemning "the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death". (102)

Mary Dyer appeared before Governor John Endicott on the 31st May, 1660. He asked if she was still a Quaker and she replied: "I own myself to be reproachfully so called." Endicott then passed his judgment: "Sentence was passed upon you the last General Court; and now likewise - You must return to the prison, and there remain till to-morrow at nine o'clock; then thence you must go to the gallows and there be hanged till you are dead.... Therefore prepare yourself tomorrow at nine o'clock." Dyer then explained her actions: " I came in obedience to the will of God the last General Court, desiring you to repeal your unrighteous laws of banishment on pain of death; and that same is my work now, and earnest request, although I told you that if you refused to repeal them, the Lord would send others of his servants to witness against them." (103)

On 1 June 1660, at nine in the morning, Mary Dyer was escorted to the gallows. While on the scaffold she was given the opportunity to save her life if she renounced her religious beliefs. She replied: "Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death. Nay, I came to keep blood guiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death, made against the innocent servants of the Lord, therefore my blood will be required at your hands who willfully do it; but for those that do is in the simplicity of their hearts, I do desire the Lord to forgive them. I came to do the will of my Father, and in obedience to his will I stand even to the death." (104)

According to Edward Burrough, Dyer died "sweetly and cheerfully" on the gallows on 1 June 1660. Burrough believed fellow Quakers believed that Mary Dyer "did hang as a flag for them to take example by". (105) Charles II responded to this event by asking Governor Endicott for less severe religious laws, and she was the last but one Quaker to be hanged in Boston. (106)

Quaker Conflict

The Restoration divided Quakers into two groups: those who found reassurance in Fox's message to trust in God and the inevitable workings of God's will, and those who expected the Society of Friends to take a more militant stance. Edward Burrough was one of those who sought confrontation with the authorities. Burrough was arrested on 1 June 1661. He refused to back down and he died aged twenty-nine in Newgate prison on 14 February 1663. (107) According to one source, during Charles II's reign, 13,562 Quakers were arrested and imprisoned in England and 198 were transported as slaves, and 338 died in prison or of wounds received in violent assaults on their meetings. (108)

Francis Howgill views were similar to Burrough. After Charles II became king he published Chosen Madness for Thy Crown (1660). Howgill was found guilty of praemunire at Appleby in 1663 after refusing to swear the oath of allegiance. This sentence being passed and he was imprisoned for life. In 1665 he showed that he no longer believed in an eventual Quaker triumph over adversity, resignedly committing himself to suffering "though the day be dark and gloomy" (109) Howgill became ill while in prison and he died on 11 February 1669. (110)

In 1661, after the death of her husband, Elizabeth Hooton travelled to America with a friend, Joanne Brooksup. They received a hostile reception when they arrived in Boston. John Endicott, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who issued judicial decisions banishing individuals who held religious views that did not accord well with those of the Puritans. He especially hated Quakers and the previous year he had ordered the execution of four of them including Mary Dyer. (111)

Hooton and Brooksup were spared this punishment but were driven for two days out into the wilderness and left to starve. They managed to make their way to Rhode Island, from where they obtained a passage to Barbados, before returning once again to Boston "to testify against the spirit of persecution there predominant" Arrested again they were put on board a ship for Virginia and eventually returned to England. (112)

In December 1661 George Fox surveyed the expansion of Quakerism across the world. He gave examples of the expansion of Quakerism across the world. It was doing extremely well in the West Indies. William Ames had made some converts in in the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Russia, Hungary and Sweden. The numbers in Scotland were increasing although many had been imprisoned for their beliefs. Quakers had been deported from Turkey and Italy and some had died in Rome's prisons. (113)

John Perrot was a missionary whose career once he returned to England created problems for Fox. He had refused to condemn James Nayler before travelling to France, Italy, Greece and Turkey. After spending long periods in prison he arrived back in England in 1661. Fox was concerned that Perrot was making a challenge for the leadership of the movement: "Perrot was accused of financial extravagance during his mission in the Mediterranean, and his writings, especially his poetry, were regarded as an offence to the principle of plainness; moreover, Fox and other prominent Quakers saw Perrot's stance on hats as vain and lacking in humility... his enthusiastic preaching, his growing popularity particularly with women Friends, and even his Rabbinic-like beard reminded them uncomfortably of Nayler. It was averred that he had taken on his ministerial role too soon, a point underlined when Perrot began to hold his own meetings in London which only helped to enhance his reputation as a schismatic." (114)

Perrot also held the conviction that men and women were equals. He applied the apostle Paul's advice to the Corronthians that women keep their heads covered in prayer to men also. He asked bluntly "What is the difference between the fleshy head of carnal man and a carnal woman, and which of them does God most respect." This created difficulties for Fox for it highlighted how Fox embraced a common social practice as well as biblical injuctions that women keep their heads covered, thus eroding their vaunted commitment to equality. (115)

Fox responded by arguing: "And so you would bring all men to sit like a company of women and so you would bring all into a form under the penalty of curse". Men must "stand in our liberty in the power of God before hats were." Women could not enjoy that same liberty because Paul had ordered their heads covered; men wearing hats amounted to an empty and accursed form, while for women it was required. (116)

Fox also came under attack from Isaac Penington, who believed Fox had made too many compromises in his attempt to stop the persecution of Quakers. While in Aylesbury gaol he published Somewhat Spoken to a Weighty Question (1661), espousing religious freedom and pacifism. (117) He was close to Perrot and two years later Penington published a long reflective essay in which he ventured that the Society of Friends, like ancient Israel, had become too well-off and self-satisfied, thus straying from its earlier purity. "The enemy is very subtle and watchful, and there is danger to Israel all along, both in the poverty and in the riches; but the greater danger is in the riches: because then man is apt to forget God, and to lose somewhat of the sense of his dependence (which keeps the soul low and safe in the life), and also to suffer somewhat of exaltation to creep upon him, which presently in a degree corrupts and betrays him." (118)

Fox became concerned about Penington's writings, especially his defence of Quaker dissenters when he called for broader toleration within the movement. Fox was also worried about Penington's Three Queries Propounded to the King and Parliament (1662) where he reminded readers that in the mid-century upheavals God had overturned the government and empowered men of low estate, and warned that he could do so again. (119) Penington received letters from Francis Howgill, William Smith and Richard Farnworth asking him to stop causing problems for Fox. "Penington accepted their counsel, including Howgill's request that he write nothing else critical of Quaker leaders." (120)

George Fox and Margaret Fell

Thomas Fell died in 1658. This deprived the Quakers of a judicial protector. Margaret Fell was left a widow, aged forty-four, with eight unmarried children. She later wrote of her husband that he had been "a tender loving husband to me, and a tender father to his children", and had "left a good and competent estate for them". (121) Margaret was left Swarthmoor Hall and 50 adjacent acres (she had already inherited the Askew estate at Marsh Grange from her father). Fell's death allowed Margaret to become an active Quaker minister who wrote and travelled and who became a political spokeswoman of the movement. She emerged as in effect a co-leader of early Quakerism with Fox. (122)

George Fox often described Margaret as the "nursing mother" of the movement. Her status and experience gave her self-assurance in her dealings with powerful men. This included communicating with Charles II over the persecution of Quakers. It was claimed that within the Society of Friends she "doled out assignments like a Quaker bishop". She was also extremely loyal to Fox and gave him her full support in his conflicts with James Nayler, John Perrot and Isaac Penington. Despite her own strong opinions she always deferred to Fox about issues within the movement. (123)

In May 1669 Fox (35) and Margaret (45) agreed to marry. In mid-October 1669 the couple duly informed the Bristol meeting of their intentions, first to the men's meeting and then to a joint meeting of men and women. They married on 27 October with Margaret's daughters and their husbands present. Margaret's only son, George Fell, who disapproved of the match, did not attend. Fox signed a contract waiving his rights to Margaret's property, and her daughters, who were to inherit Swarthmoor Hall should she remarry, agreed to allow her to live there. A few days after the wedding Fox continued on his missionary visits while Margaret returned to Swarthmoor. (124)

It has been argued that there "were no passionate feelings on either side" and that Fox expressed "all the excitement of someone completing a business deal". (125) In an explanatory letter addressed to all Quakers Fox said he had been "commanded" to take Margaret as his wife and added that the marriage testifed to "the church coming out of the wilderness, and the marriage of the Lamb before the foundation of the world". (126) Fox wanted it to be understood that his was an "honorable marriage and in an undefiled bed" in an effort to undermine the rumours of sexual misconduct between the two by anti-Quaker authors such as John Harwood. (127)

Although she was 55 years old Margaret told friends that she hoped to give birth to another child. The couple spent ten days together before Fox continued his missionary work. In April 1670, Margaret was arrested and detained at Lancaster jail. She claimed that she was pregnant and this news was welcomed by other Quakers. However, no baby was born and it has been suggested that Margaret had convinced herself that she was carrying a child, a condition known as pseudocyesis (imaginary or false pregnancy). (128)

The Colonies and Slavery

In August 1671 George Fox and twelve other Quakers left England to visit the colonies. One of the main reasons was to eradicate pockets of settlers who were supporters of John Perrot. Their ship arrived in Barbados on 3 October. Quakers were the second largest religious denomination on the island and they owned five meeting houses. They tended to own some of the largest plantations and depended for their success on slave labour. Quakers averaged twelve slaves per household. (129)

It was claimed that some Quakers who lived in Barbados, under the influence of Perrot, permitted men to wear hats when they prayed. Fox issued stern warnings about this and insisted they follow the "order of the gospel". He also condemned acts of sexual immorality. He told a meeting of women that men with the "evil custom" of "running after another women when married to one already" should be forced to break off their illicit relationships." (130)

Fox was keen to point out that Quakers supported slavery. He denied that Quakers promoted slave unrest and that meetings for slaves taught them "justice, sobriety, temperance, charity, and piety, and to be subject to their masters and governors," not prescriptions for insurrection. (131) As H. Larry Ingle points out: "In a colony, where potentially insuordinate blacks comprised two-thirds of the population, whose economic well-being rested squarely on slave labour, and whose social cohesion depended on black's submission to their white masters, this matter was more critical than the subtleties of theological beliefs." (132)

In his journal Fox claimed he exhorted the blacks "to be sober & to fear God and to love their masters and mistresses, and to be faithful and diligent in their masters service & business & that then their masters & overseers will love them and deal kindly & gently with them". The slaves were not to beat their wives, steal, drink, swear, lie, or commit fornication. Whites and blacks had the same path to heaven, and masters had a responsibility for religious training of their families. There was no mention of eventual freedom for the black servants. (133)

However, in a pamphlet published five years later, Fox advocated freeing slaves after a period of years, using an analogy to a similar practice of the jubilee year discussed in the books of Exodus and Jeremiah. Fox also advocated the humane treatment of slaves, proclaimed that Christ died for all people - whites, blacks, and Indians - and insisted upon the necessity of treating the marriages of blacks like those of whites. (134)

It has been argued by J. William Frost that "Fox's attitudes appear very progressive as compared to virtually all other Quaker and non-Quaker visitors to the West Indies." Frost admits that in some ways Fox's attitudes remain puzzling. "The most likely explanation is that Fox's language closely paralleled that of the Scriptures, and the biblical terms were strangers, heathen, bondsmen, servants, but not slaves. Fox assumed that converting both masters and slaves would end the immorality and abuses that he found in both parties. He condemned the lack of marriage and frequency of adultery in slavery, holding the masters and the blacks responsible, but never mentioned the pervasive physical cruelty and near-starvation of the slaves. Fox's Gospel Family-Order shows little moral indignation about the treatment of slaves in the West Indies." (135)

Over the next ten years George Fox sent several epistles to Quakers in areas with significant slave populations. He was mainly concerned with the religious training of black servants but never addressed their eventual freedom. Nor did he ever appear to have ever questioned the legitimacy of slavery. Fox never advocated slavery unlike the other main leader of the movement, William Penn. His reputation for fair treatment of Native Americans is well deserved; his lack of interest in anti-slavery is equally significant. Penn while in America bought and sold slaves. (136)

Katharine Gerbner has argued: "When Pennsylvania was founded in 1682, William Penn and others used their Quaker connections in Barbados to purchase enslaved Africans. As Pennsylvania's social and economic structure developed, ties with the West Indies and other trade outlets flourished. The trade with Barbados was a source of pride and a symbol of prosperity for many English Quakers who considered slavery to be necessary for economic development.... Like other stories that are shameful or embarrassing, this one had been largely suppressed in the Quaker histories that I read." (137)

On 8th January, 1672, Fox and his entourage sailed for Jamaica. The largest English possession in the West Indies, the island had been the site of Quaker missionary activity since it was seized it from the Spanish in 1655. Fox inaugurated disciplinary meetings for men and women to control dissidents. John Perrot had died on the island seven years previously and Fox was pleased to see that he was accepted as the leader of the movement. (138)

The next destination for George Fox was Maryland. This was mainly a Catholic settlement but they had a policy of religious tolerance and so Quakers were allowed to live in the area. Tobacco was the chief crop and the plantations used slave-labour. Fox moved on to Rhode Island that was under the control of Roger Williams, a strong supporter of religious toleration. Fox was upset to discover the large number of Ranters on the island. At the time Rhode Island was a "heretic's haven" but had been nicknamed "Rogues' Island" or "Island of Errors". (139)

Fox arrived home on 28th June, 1673. Only two of his original party returned with him. The saddest absence was that of Elizabeth Hooton, his first convert more than twenty-five years earlier who had died while they were in Jamaica. Fox was happy that Quakerism was developing into a worldwide movement. Fox was elated by the large number of convincements in America and he now developed a regular network to channel books from England to Quakers in the colonies. (140)

Quakerism: 1673-1694

In September 1662 Charles II had announced the Declaration of Indulgence that suspending laws against dissenters. This resulted in the release of 491 Quakers from prison. An angry House of Commons forced the king to withdraw the declaration and implement, in its place, the Test Act (1673). Although aimed at Catholics, Fox saw that this law could be applied to them because of their testimony against oaths and protested vigorously against it. William Penn was the main figure in Parliament who argued against this legislation. (141)

On 17th December, 1673, Fox was arrested and sent to Worcester Jail. He was twice freed briefly on writs of habeas corpus and allowed to go to London. However, he was unwilling to accept a pardon and returned to prison. Fox fell ill, and for a time became so weak he could hardly utter a word and needed fresh air in his closed dungeon. He spent fourteen months in prison until his final release in February 1675. (142)

Fox now concentrated on sorting out the conflict that emerged between men and women in Bristol. Isabel Yeamans, the daughter of Margaret Fell, had upset men in the city by setting up a monthly meetings for women. This was in response to her mother's call for women's rights in Quaker meetings in Women's Speaking Justified (1666) where she argued: "Let this Word of the Lord, which was from the beginning, stop the Mouths of all that oppose Women's Speaking in the Power of the Lord; for he hath put Enmity between the Woman and the Serpent; and if the Seed of the Woman speak not, the Seed of the Serpent speaks; for God hath put Enmity between the two Seeds; and it is manifest, that those that speak against the Woman and her Seed's Speaking, speak out of the Envy of the old Serpent's Seed." (143)

William Rogers, a leading Quaker in the city, demanded to know why the women had proceeded on their own. A committee of six, including some of the most powerful Quakers in Bristol, was instructed to attend the next women's meeting to discuss the matter. The women eventually agreed to defer "to the wisdom of God in the Friends of the men's meeting". At a meeting of thirty male Quakers it was agreed that in future women had a "duty to mind only those things that tend to peace." The Bristol women acquiesced to this demand. (144)

Fox, who had been in America at the time of this dispute, published details of new rights for women in the movement. He instructed that couples seeking to be married must have their proposed union examined twice by both men's and women's meetings. This was confirmed in a letter to his wife in May 1674. (145) In an epistle the following year Fox defended women's meetings in general terms, rebuking those who called them into question, but it neglected to address what many male Quakers considered the demeaning requirement that men seek approval for marriage from women. (146)

At a meeting in May 1675, Quaker leaders in London, including William Penn, Thomas Salthouse. Alexander Parker and George Whitehead, published a document concerning the role of women in the movement. It stated that all marriages be cleared twice by women's and men's meetings, to make sure that "all foolishand unbridled affections" be speedily brought under God's judgment. It also reminded Quakers that women's meetings, just like men's meetings, had been set up with God's counsel and sharply admonished those who sneered at them as "synods" and "Popish impositions". Violators of these instructions - "disorderly walkers" - should have their names recorded. (147)

It has been claimed by one Quaker historian "Separate men's and women's Business Meetings were recommended at all levels of the structure, each with their own areas of responsibility. Fox argued this was necessary for women to have their own voice, although their areas of influence were highly gendered and limited to pastoral duties such as marriage arrangements and poor relief. It seems that whilst the ideal of spiritual equality persisted, political equality did not." (148)

One of the main opponents of women's meetings was Anne Docwra. She argued that St Paul had debarred women from having authority over men; women, however, could prophesy and guide men Friends in the administration of charity funds. (149) In April 1683, Docwra visited Fox in London to discuss these matters. She had heard from a relative that he was as "big as two or three, and spent his time dozing, in a near stupor from liquor and brandies". Instead she found "a big man, true, taller than average, big boned, his face rounded, a bit on the fat side, but not incapacitated." Anne added "he moved stiffly, and his hands and fingers were so puffy he could not write". However, she left impressed with the way he supported women's meetings. (150)

Fox was in poor health and William Penn became the unofficial leader of the Quakers. He enjoyed a good relationship with King Charles II and in 1681 he suggested that there should be a mass emigration of English Quakers. Some Quakers had already moved to North America, but Puritans were as hostile towards Quakers as Anglicans in England were and some of the Quakers had been banished to the Caribbean. The king, who owed the Penn family a considerable amount of money, handed over a large piece of land that included the present-day states of Pennsylvania and Delaware. Penn immediately set sail and took his first step on American soil in 1682. Penn gave Fox 1,266 acres of land, but he was too ill to take it up. (151)

The authorities continued to persecute Quakers. Margaret Fox was arrested for holding weekly meetings at Swarthmoor Hall. She was fined £100 for praying and preaching in her own house, and twenty-four cattle were confiscated. Her son-in-law, Daniel Abraham was assaulted by an army officer when an armed force carted off wheat from the barn. Margaret petitioned the king over the matter but her complaints were ignored. (152)

James II became king on 6th February, 1685. Well-connected Quakers such as William Penn and Robert Barclay, began talks with the king about the plight of those imprisoned for their religious beliefs. On 15 March, 1686, the king issued a pardon to all those imprisoned because of a failure to attend the established church; as a result of this pardon, around sixteen hundred Quakers were released. Fox welcomed this move and blessed "the Lord for King James" and claimed that the "hearts of the king and rulers have been opened". (153)

With the replacement of James by William III and Mary II during the 1688 Glorious Revolution, Fox and Penn lost influence with the monarchy. However, Parliament did pass the Toleration Act of 1689. The Act allowed for freedom of worship to nonconformists who had pledged to the oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy and rejected transubstantiation, i.e., to Protestants who dissented from the Church of England such as Quakers, Baptists, Congregationalists or Presbyterians, but not to Roman Catholics. (154)

In his final years George Fox lived in London. Margaret Fell continued to live in Swarthmoor Hall. However, in April, 1690, aged seventy-six, did visit her husband. On 11 January 1691, Fox attended the Gracechurch Street meeting and, as usual, preached. At the end of the meeting he complained of a "coldness near his heart" and went to bed at the nearby house of Henry Gouldney, a local Quaker with whom Fox had stayed several times before. He died of congestive heart failure two days later. (155)

Three years after Fox's death, a committee of leading Quakers under the leadership of William Penn, decided to publish his journals. George Fox's Journal (1694). Thomas Ellwood, was appointed as editor. According to H. Larry Ingle "under their supervision, Ellwood toned down or omitted many events they considered most bizarre." The journal described Fox's visions, his teachings and his frequent imprisonments. The first sixteen pages of Fox's memoir were either lost or destroyed, so we have to rely on Ellwood's account of his leader's early life. (156)

It has been claimed that the book has distorted the history of the movement. Some people, for example Elizabeth Hooton, the first person Fox convinced, receive no more than occasional mentions, despite the major part she played as a Quaker minister. "The Journal emphasizes those aspects of the movement most associated with Fox himself (the great open-air rallies and disputations) at the expense of others (the brilliantly planned and executed publicity drives and the co-ordinated tithe-strikes) in which he was less involved. It was also a product of the struggle against dissent within the movement, reflecting the period of its composition. Fox casually excluded from his narrative or played down the role of several people who had once occupied prominent positions in the movement.... Moreover, Fox never concedes, much less confesses, any errors on his part: here is a man always in the right, sure of himself and his role, and convinced beyond any human doubt that he will be victorious in the end." (157)

Primary Sources

(1) George Fox, Journal, introduction by Thomas Ellwood (1694)

The blessed instrument of and in this day of God, and of whom I am now about to write, was George Fox, distinguished from another of that name, by that other's addition of younger to his name in all his writings; not that he was so in years, but that he was so in the truth; but he was also a worthy man, witness and servant of God in his time.

But this George Fox was born in Leicestershire, about the year 1624. He descended of honest and sufficient parents, who endeavoured to bring him up, as they did the rest of their children, in the way and worship of the nation; especially his mother, who was a woman accomplished above most of her degree in the place where she lived. But from a child he appeared of another frame of mind than the rest of his brethren; being more religious, inward, still, solid, and observing, beyond his years, as the answers he would give, and the questions he would put upon occasion manifested, to the astonishment of those that heard him, especially in divine things.

His mother taking notice of his singular temper, and the gravity, wisdom, and piety that very early shone through him, refusing childish and vain sports and company when very young, she was tender and indulgent over him, so that from her he met with little difficulty. As to his employment, he was brought up in country business; and as he took most delight in sheep, so he was very skilful in them; an employment that very well suited his mind in several respects, both for its innocency and solitude; and was a just figure of his after ministry and service.

I shall not break in upon his own account, which is by much the best that can be given; and therefore desire, what I can, to avoid saying anything of what is said already, as to the particular passages of his coming forth; but, in general, when he was somewhat above twenty, he left his friends, and visited the most retired and religious people, and some there were at that time in this nation, especially in those parts, who waited for the consolation of Israel night and day, as Zacharias, Anna, and good old Simeon did of old time. To these he was sent, and these he sought out in the neighboring countries, and among them he sojourned till his more ample ministry came upon him.

At this time he taught and was an example of silence, endeavouring to bring people from self-performances, testifying and turning to the light of Christ within them, and encouraging them to wait in patience to feel the power of it to stir in their hearts, that their knowledge and worship of God might stand in the power of an endless life, which was to be found in the Light, as it was obeyed in the manifestation of it in man. "For in the Word was life, and that life was the light of men." Life in the Word, light in men, and life too, as the light is obeyed; the children of the light living by the life of the Word, by which the Word begets them again to God, which is the regeneration and new birth, without which there is no coming unto the kingdom of God; and which, whoever comes to, is greater than John, that is, than John's ministry which was not that of the kingdom, but the consummation of the legal, and opening of the gospel-dispensation. Accordingly, several meetings were gathered in those parts; and thus his time was employed for some years.

(2) Francis Higginson, A Brief Relation of the Irreligion of the Northern Quakers (1653)

And first for their Meetings, and the manner of them. They come together on the Lord's days, or on other days of the week indifferently, at such times and places, as their speakers or some other of them think fit. Their number is sometimes thirty, sometimes forty, or sixty, sometimes a hundred, or two hundred in a swarm. The places of their meetings are for the most part, such private houses as are most solitary; and remote from neighbours, situated in dales and by-places: Sometimes the open fields, sometimes the top of an hill, or rocky hollow places, on the sides of mountains, are the places of their rendezvous. In these their assemblies for the most part they use no prayer: Not in one meeting of ten, and when they do, their praying devotion is so quickly cooled, that when they have begun, a man can scarce tell to twenty before they have done. They have no singing of psalms, hymns, or spiritual songs, that is an abomination. No reading or exposition of holy scripture, this is also an abhorrence. No teaching, or preaching, that is in their opinion the only thing that is needless. No administration of sacraments; with them there is no talk (they say) of such carnal things, not so much as any conference by way of question is allowed of: That which asks, they say, doth not know, and they call propounding of any question to them, a tempting of them. They have only their own mode of speaking (that is all the worship that I can hear of) which they do not call, but deny to be preaching; nor indeed doth it deserve that more honourable name. If any of their chief speakers be among them, the rest give place to them; if absent, any of them speak, that will pretend a revelation; sometimes girls are vocal in their convents, while leading men are silent: Sometimes after they are congregated, there is not a whisper among them for an hour or two, or three together. This time they are waiting which of them the spirit shall come down upon, in inspirations and give utterance unto.