New Model Army

At the beginning of the war, Parliament relied on soldiers recruited by large landowners who supported their cause. Oliver Cromwell soon realised that these soldiers would not be good enough to defeat the Cavaliers. He pointed out in a letter to his cousin, John Hampden, about his regiment: "Your troopers are most of them old decayed serving men... the royalists' troopers are gentleman's sons, younger sons, persons of quality. Do you think that the spirits of such base and mean fellows will be ever able to encounter gentleman that have honour, courage and resolution in them? You must get men of a spirit... that is likely to go on as far as a gentleman will go, or else I am sure you will be beaten still." (1)

Cromwell recruited men who shared his "Puritan religious zeal". He also imposed strict discipline. When in April 1643, two troopers tried to desert, he had them whipped in the market place. Men who was heard to swear they would be fined "twelvepence; if he be drunk he is set in the stocks, or worse". Cromwell was careful about who he selected as officers. The Earl of Manchester complained that he did employ "men of estates" but "common men, poor and of mean parentage". He added that they were always very religious men. (2)

Jasper Ridley, the author of The Roundheads (1976) argues: "Cromwell's military genius, combined with his Puritan religious zeal, made him the perfect military leader in a revolutionary war. He was fighting for liberty of conscience and freedom of worship for the extremist Protestant sects, which were threatened by his Church of England and Presbyterian allies as well as by his Cavalier enemies." (3)

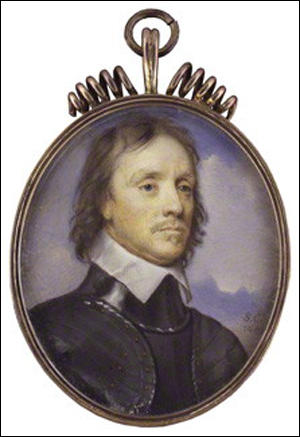

© National Portrait Gallery

Cromwell became convinced that some of the leaders of the Parliamentary Army were not committed to the destruction of the Royalist Army. He was a strong supporter of the Self-Denying Ordinance, where all peers and MP's should be removed from army and navy commands, including, Edward Montagu, the Earl of Manchester, Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex and Robert Rich, the Earl of Warwick and William Waller. At first, the House of Lords threw out the recommendation but with some changes it was eventually accepted. (4)

In February 1645, the House of Commons decided to form a new army of professional soldiers. This became known as the New Model Army. It was made up of ten cavalry regiments of 600 men each, twelve foot regiments of 1,200 men, and one regiment of 1,000 dragoons. General Thomas Fairfax, was appointed as its commander-in-chief. The new army contained a larger number of ideologically-committed soldiers and officers than any other army that had taken the field so far. Cromwell was quoted as saying: "I would rather have a plain russett-coated captain that know what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman and nothing else." (5)

Oliver Cromwell, as a MP, had to resign his command. However, a few weeks later, General Fairfax, gave him the rank of Lieutenant-General and he took charge of the cavalry. Members of the New Model Army received proper military training and by the time they went into battle they were very well-disciplined. In the past, people became officers because they came from powerful and wealthy families. In the New Model Army men were promoted when they showed themselves to be good soldiers. For the first time it became possible for working-class men to become army officers. Oliver Cromwell thought it was very important that soldiers believed strongly in what they were fighting for. Where possible he recruited men who, like him, held strong Puritan views and the New Model Army went into battle singing psalms, convinced that God was on their side. (6)

The New Model Army took part in its first major battle just outside the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire on 14 June 1645. The battle began when Prince Rupert led a charge against the left wing of the parliamentary cavalry which scattered and Rupert's men then gave chase. While this was going on Cromwell launched an attack on the left wing of the royalist cavalry. This was also successful and the royalists that survived the initial charge fled from the battlefield. While some of Cromwell's cavalry gave chase, the majority were ordered to attack the now unprotected flanks of the infantry. Charles I was waiting with 1,200 men in reserve. Instead of ordering them forward to help his infantry he decided to retreat. Without support from the cavalry, the royalist infantry realised their task was impossible and surrendered. (7)

The battle was a disaster for the king. His infantry had been destroyed and 5,000 of his men, together with 500 officers, had been captured. The Parliamentary forces were also able to capture the Royalist baggage train that contained his complete stock of guns and ammunition. The women of the royalist camp were treated with great cruelty; those from Ireland were killed, while those from England had their faces slashed with daggers. Cromwell said after the battle that "this is none other than the hand of God, and to Him alone belongs the glory". (8)

Primary Sources

(1) Joshua Sprigge wrote about the New Model Army in Anglia Redivia (1647)

The officers of this army, as you may read, are such, as knew little of war, than our own unhappy wars had taught them, except some few, so as men could not contribute much to this work: indeed I may say this, they were better Christians than soldiers, and wiser in faith than in fighting, and could believe a victory sooner than contrive it; and yet I think they were as wise in the way of soldiery as the little time and experience they had could make them.

These officers, many of them with their soldiery, were much in prayer and reading scripture, an exercise that soldiers till of late have used bur little, and thus then went on and prospered: men conquer better as they are saints, than soldiers; and in the countries where they came, they left something of God as well as of Caesar behind them, something of piety as well as pay.

They were much in justice upon offenders, that they might be still in some degree of reformation in their military state. Armies are too great bodies to be found in all parts at once.

The army was (what by example and justice) kept in good order, both respectively to itself, and the country: nor was it their pay that pacified them; for had they not had more civility than money, things had not been so fairly managed.

They were many of them differing in opinion, yet not in action nor business; they all agreed to preserve the kingdom; they prospered more in their unity, than uniformity; and whatever their opinions were, yet they plundered none with them, they betrayed none with them, nor disobeyed the state with them, and they were more visibly pious and peaceable in their opinions, than many we call more orthodox.

They were generally constant and conscientious in duties, and by such soberness and strictness conquered much upon the vanity and looseness of the enemy; many of those fought by principle as well as pay, and that made the work go better on, where it was not made so much matter of merchandise as conscience: they were little mutinous or disputing commands; by which peace the war was better ended.

There was much amity and unity amongst the officers, while they were in action, and in the field, and no visible emulations and passions to break their ranks, which made the public fare better. That boat can go but slowly where the oars row several ways; the best expeditions is by things that go one way.

The army was fair in their marches to friends, and merciful in battle and success to enemies, by which they got love from enemies, though more from friends.

This army went on better by two more wheels of treasurers and a committee; the treasurers were men of public spirits to the state and the army, and were usually ready to present some pay upon every success, which was like wine after work, and cheered up the common spirits to more activity.

The committee, which the House of Commons formed, were men wise, provident, active and faithful in providing ammunition, arms, recruits of men, clothes: and that family must needs thrive that hath good stewards.

Student Activities

Military Tactics in the Civil War (Answer Commentary)