Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell, the son of Robert Cromwell and Elizabeth Steward Cromwell, was born in Huntingdon on 25th April 1599. Oliver's great-grandfather, Morgan Williams, a Welshman who had settled in Putney as an innkeeper and brewer, had the good fortune to marry Katherine, the sister of Thomas Cromwell, before he was employed as chief minister by Henry VIII. (1)

During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Morgan and his son, Richard, received enough confiscated church lands to become one of the most prominent families in Huntingdonshire. This included three abbeys, two priories and a nunnery, that was worth about £2,500 a year. In gratitude, Richard changed the family name to Cromwell.

By the time Oliver was born, Robert Cromwell's older brother, Sir Oliver Cromwell owned a large but debt-laden estate. Robert in contrast inherited a modest cluster of urban properties in and around the town and had an income of around £300 per annum and a seven-room town house. However, he had considerable social status and had represented Huntington in the parliament of 1593. (2)

Oliver attended Huntington Grammar School. Dr Thomas Beard was not only the schoolmaster but the rector of St John's Church. He was also a sincere Puritan who had written pamphlets on the doctrine of predestination (the doctrine that all events have been willed by God). One of these pamphlets argued that the Pope was the Anti-christ. Although he later developed strong religious views, as a schoolboy he was not a good student: "He was of a stubborn disposition that made correction difficult; he played truant, he broke down hedges and stole the birds from the dovecotes." (3)

Oliver Cromwell and Puritanism

It is claimed that he was a spoilt child because he was the only boy in a family of six sisters (three other children had died in infancy). "We may speculate on the effects of this petticoat environment; by all accounts (some of them not very reliable) he grew up to be a rough, boisterous, practical-joking boy, with no effeminate characteristics." (4) According to one source "Cromwell had an unusually close, tender and long-term relationship with his mother". (5)

In April 1616 he began attending Sidney Sussex College. The Master of the College was Samuel Ward and he was accused of making it "a hotbed of Puritanism". He did well in mathematics but does not appear to have been very interested in "the humanities and civil law" to the dismay of his parents. It seems that during this period he had a great enthusiasm for "football, cudgelling, wrestling and an early form of cricket". (6)

Cromwell left Cambridge University in June, 1617, on the death of his father and took over control of the family estate. On 22nd August 1620, Oliver Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier. His wife was the daughter of Sir John Bourchier, a London merchant, a fur-dealer and leather dresser, who had done well enough to be knighted and buy a country estate in Essex. In his first years of married life he consulted a London physician who recorded in his case-book that Cromwell was "depressed to an abnormal degree". Another doctor suggested that he suffered from hypochondria. (7)

Over the next few years Elizabeth Cromwell gave birth to nine children: five boys and four girls. Only one child (James) died in infancy. Little is known of the relationship between Oliver and Elizabeth beyond the unmannered deep affection of their letters to one another. His marriage brought him into contact with leading members of the London merchant community. It could have also been the reason for his conversion to Puritanism during this period. (8)

Cromwell wrote afterwards: "You know what my manner of life hath been. Oh, I lived in and loved darkness, and hated the light. I was a chief, the chief of sinners. This is true: I hated godliness, yet God had mercy on me. Oh the riches of his mercy! Praise Him for me, pray for me, that he who hath begun a good work would perfect it to the day of Christ." (9)

In 1628, Oliver Cromwell's childless uncle, Richard Cromwell died, leaving his property to his nephew. The following year he was involved in a dispute with a local powerful landowner. It is believed that his new hard-line religious views was a factor in this conflict. Jasper Ridley suggests that Cromwell "championed the cause of the local commoners against the Mayor of Huntingdon who was threatening their privileges, and against the attempts of the Earl of Manchester to enclose the Fens." In December, 1630, he was called before the Privy Council and forced to apologize. In May, 1631, he sold nearly all of his land in Huntingdon for the sum of £1,800 and moved to St Ives, 4 miles away. (10)

John Morrill has pointed out: "Despite his connections with ancient riches, Cromwell's economic status was much closer to that of the middling sort and urban merchants than to the country gentry and governors. He always lived in towns, not in a country manor house; and he worked for his living. He held no important local offices and had no tenants or others dependent upon him beyond a few household servants." (11)

Conflict with the King

During this period Cromwell came into conflict with Charles I, who attempted to make money from selling knighthoods. In the 16th century, all men with land worth £40 a year were required to pay for a knighthood. However, rapid inflation pushed many into this category "who were below the social level of knights and had no relish for an honour which might well oblige them to perform functions in the local communities for which they had neither the leisure, the qualifications, nor the necessary status." (12)

Cromwell and other Puritans refused to buy what had once been an honour. Charles reacted to this by fining those who were unwilling to pay this money. In April 1631 Cromwell and six others from his neighbourhood appeared before the royal commissioners for repeatedly refusing to buy a knighthood. He was found guilty and fined £10. It was reported that Cromwell was so unhappy about this that he considered the idea of going to live in North America. (13)

Oliver Cromwell also came into conflict over the issue of the Ship Tax. In 1635 Charles I faced a financial crisis. Unwilling to summon another Parliament, he had to find other ways of raising money. He decided to resort to the ancient custom of demanding Ship Money. In the past, whenever there were fears of a foreign invasion, kings were able to order coastal towns to provide ships or the money to build ships.

Charles sent out letters to sheriffs reminding them about the possibility of an invasion and instructing them to collect Ship Money. Encouraged by the large contributions he received, Charles demanded more the following year. Whereas in the past Ship Money had been raised only when the kingdom had been threatened by war, it now became clear that Charles intended to ask for it every year. Several sheriffs wrote to the king complaining that their counties were being asked to pay too much. Their appeals were rejected and the sheriff's now faced the difficult task of collecting money from a population overburdened by taxation. (14)

Gerald E. Aylmer has argued that ship money was in fact a more reasonable tax than the traditional forms of collecting money from the population. Most king's had relied on taxes on movable property (a subsidy). "Ship money had in fact been a more equitable as well as a more efficient tax than the subsidy because it was based on a far more accurate assessment of people's wealth and property holdings." (15)

At the beginning of 1637, twelve senior judges had declared that, in the face of danger to the nation, the king had a perfect right to order his subjects to finance the preparation of a fleet. In November, John Hampden was prosecuted for refusing to pay the Ship Money on his lands in Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. The court case was a test of power between sovereign and subject. The judges voted seven against five in favour of conviction but the publicity surrounding the case made Hampton one of the most popular men in England. (16) More importantly, if "ship money was legal, non-parliamentary government had come to stay". (17)

Cromwell, who was Hampden's cousin, was a strong opponent of the Ship Tax. He argued that such a tax was "a prejudice to the liberties of the kingdom" and that there should be no taxation without the consent of Parliament. One of the critics of the tax said "he knew no law besides Parliament to persuade men to give away their own goods". Cromwell agreed and said he was "a great stickler" against the tax. During this period Cromwell developed a local reputation among those opposed to Charles's government. (18)

In 1636 Oliver Cromwell's widowed maternal uncle, Sir Thomas Steward, died childless, leaving most of his estate to him. He inherited from him leases on tithes held by the Church. Cromwell was now a man of considerable wealth and moved to a substantial glebe house close to Ely Cathedral. His income now increased dramatically to some £300 a year. (19)

However, like his uncle, he held strong views about protecting the poor people. Steward had resisted the draining of the Fens in the interests of the poor commoners and Fen dwellers and on one occasion had prevented food riots by rounding up grain speculators. In 1638 it was reported that Cromwell had argued that the poor "Should enjoy every foot of their common". (20)

Cromwell was now forty-years old. "Cromwell was of singular appearance. The London doctor whom he had consulted noted that he had pimples upon his face. These seem to have been supplanted by warts on his chin and forehead. His thick brown hair was always worn long over the collar, and he had a slim moustache; a tuft of hair lay just below his lower lip. He had a prominent nose... his eyes, in colour somewhere between green and grey... He was about 5 feet 10 inches in height" and according to this steward, John Maidstone, "his body was well compact and strong" and had a "fiery" temperament but was "compassionate" like a woman. (21)

House of Commons

In March 1640 Cromwell was elected to represent Cambridge in the House of Commons. It has been claimed that Cromwell was the "least wealthy man" who attended that Parliament. Cromwell took up the case of John Lilburne, who in February, 1638, had been found guilty and sentenced to be fined £500, whipped, pilloried and imprisoned for publishing Puritan books. The following month he was whipped from Fleet Prison to Old Palace Yard. It is estimated that Lilburne received 500 lashes along the way, making 1,500 stripes to his back during the two-mile walk. An eyewitness account claimed that his badly bruised shoulders "swelled almost as big as a penny loaf" and the wheals on his back were larger than "tobacco-pipes." (22)

When he was placed in the pillory he tried to make a speech praising John Bastwick and was gagged. Lilburne's punishment turned into an anti-government demonstration, with cheering crowds encouraging and supporting him. While in prison Lilburne wrote about his punishments, in his pamphlet, The Work of the Beast (1638). He reported on how he was tied to the back of a cart and whipped with a knotted rope. (23)

"Cromwell spoke with a great passion, thumping the table before him, the blood rising to the face as he did so. To some he appeared to be magnifying the case beyond all proportion. But to Cromwell this was the essence of what he had come to put right: religious persecution by an arbitrary court." (24) After a debate on the issue in November, 1640. Parliament voted to release him from prison. (25) Lilburne's supporters continued to protest about the way he had been treated and on 4th May 1641, Parliament resolved that the Star Chamber sentence against him had been "bloody, wicked, cruel, barbarous, and tyrannical", and voted him monetary reparations. (26)

During this period Cromwell emerged as one of the king's main critics. "In those opening months he served on eighteen high-profile committees, especially those concerned with investigating religious innovation and abuse of ecclesiastical power. His faith and trust in God made him fearless. And more than once he spoke his mind too forcefully and was reproved by the house. Sir Philip Warwick, a supporter of the monarchy, described Cromwell as someone who "wore... a plain cloth-suit, which seemed to have been made by a poor tailor; his shirt was plain, and not very clean; and I remember a speck or two of blood upon his collar... his face was swollen and red, his voice sharp and untunable, and his speech full of passion." (27)

Cromwell developed a close relationship with John Pym, the unchallenged leader of the Puritans in the House of Commons. Pym was a large landowner in Somerset. He was known for his anti-Catholic views and saw Parliament's role as safeguarding England against the influence of the Pope: "The high court of Parliament is the great eye of the kingdom, to find out offences and punish them". However, he believed that the king, who had married Henrietta Maria, a Catholic, was an obstacle to this process: "we are not secure enough at home in respect of the enemy at home which grows by the suspending of the laws at home". (28)

Pym was a believer in a vast Catholic plot. Some historians agree with Pym's theory: "Like all successful statesmen, Pym was up to a point an opportunist but he was not a cynic; and self-delusion seems the likeliest explanation of this and his supporters' obsession. That there was a real international Catholic campaign against Protestantism, a continuing determination to see heresy destroyed, is beyond dispute." (29)

Puritans and many other strongly committed Protestants were convinced that Archbishop William Laud and Thomas Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford, were the main figures behind this conspiracy. Wentworth was arrested in November, 1640, and sent to the Tower of London. Charged with treason, Wentworth's trial opened on 22nd March, 1641. The case could not be proved and so his enemies in the House of Commons, lead by Pym, resorted to a Bill of Attainder. Charles I gave his consent to the Bill of Attainder and Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, was executed on 12th May 1641. (30)

Archbishop Laud was also taken into custody. One member of parliament, Harbottle Grimstone, described Laud as "the root and ground of all our miseries and calamities". Other bishops, including Matthew Wren of Ely, and John Williams of York, were also sent to the Tower. In December, 1641, Pym, introduced the Grand Remonstrance, that summarised all of Parliament's opposition to the king's foreign, financial, legal and religious policies. It also called for the expulsion of all bishops from the House of Lords. (31)

In the last week of December it was further agreed that parliament should meet at fixed times with or without the co-operation of the king. The Triennial Act was passed to compel parliaments to meet every three years. The Venetian ambassador to London reported that "if this innovation is introduced, it will hand over the reigns of government completely to Parliament, and nothing will be left to the king but mere show and a simulacrum of reality, stripped of credit and destitute of all authority". (32)

English Civil War

Charles I realised he could not allow the situation to continue. He decided to remove the leaders of the rebels in Parliament. On 4th January 1642, the king sent his soldiers to arrest John Pym, Arthur Haselrig, John Hampden, Denzil Holles and William Strode. The five men managed to escape before the soldiers arrived. Members of Parliament no longer felt safe from Charles and decided to form their own army. After failing to arrest the Five Members, Charles fled from London and formed a Royalist Army (Cavaliers) whereas his opponents established a Parliamentary Army (Roundheads). (33)

Attempts were made to negotiate and end to the conflict. On 25th July the king wrote to the vice-chancellor of Cambridge University inviting the colleges to assist him in his struggle. When they heard the news, the House of Commons sent Cromwell with 200 lightly armed countrymen to blocked the exit road from Cambridge. On 22nd August, the king "raised his standard" at Nottingham, and in doing so marked the beginning of the English Civil War. At a time when most Englishmen were dithering and waiting upon events, Cromwell decided to take action and captured Cambridge Castle and seized its store of weapons. Soon afterwards he was given the rank of Captain and assigned to the cavalry commanded by Sir Philip Stapleton. (34)

The king marched around the Midlands enlisting support before marching on London. It is estimated he had about 14,000 followers by the time he encountered the Parliamentary Army at Edgehill on 22nd October, 1642. Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, only had 3,000 cavalry against the 4,000, serving the king. He therefore decided to wait until the rest of his troops, who were a day's march behind, arrived.

The battle began at 3 o'clock in the afternoon of the 23rd October. Prince Rupert and his Cavaliers made the first attack and easily defeated the left-wing of the Parliamentary forces. Henry Wilmot also had success on the right-wing but Stapleton and Cromwell were eventually able to repel the attack. Colonel Nathaniel Fiennes, later recalled that Cromwell "never stirred from his troops" and fought until the Cavaliers retreated. (35)

Prince Rupert's cavalrymen lacked discipline and continued to follow those who ran from the battlefield. John Byron and his regiment also joined the chase. The royalist calvary did not return to the battlefield until over an hour after the initial charge. By this time the horses were so tired they were unable to mount another attack against the Roundheads. The fighting ended at nightfall. Neither side had one a decisive advantage. (36) A pamphlet published at the time commented: "The field was covered with the dead, yet no one could tell to what party they belonged... Some on both sides did extremely well, and others did ill and deserved to be hanged." (37)

After serving at Edgehill, he was promoted to the rank of colonel and served under, Edward Montagu, the Earl of Manchester, in East Anglia. He won a number of minor victories in Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Lincolnshire. In January 1644 he was appointed Lieutenant-General and second-in-command under Manchester. "Cromwell's military genius, combined with his Puritan religious zeal, made him the perfect military leader in a revolutionary war. He was fighting for liberty of conscience and freedom of worship for the extremist Protestant sects, which were threatened by his Church of England and Presbyterian allies as well as by his Cavalier enemies." (38)

On 2nd July 1644, Oliver Cromwell took part in the battle at Marston Moor. He commanded the left wing of the Parliamentary Army, consisting of his own eastern cavalry and three regiments of Scots cavalry. Cromwell himself received a nasty flesh wound in the neck early on and needed treatment, but he returned in time to take responsibility for the final, decisive charge. (39) The battle lasted two hours. Over 3,000 Royalists were killed and around 4,500 were taken prisoner. The Parliamentary forces lost only 300 men. Cromwell spoke of it as "an absolute victory obtained by the Lord's blessing upon the godly party principally… God made them as stubble to our swords". (40)

Christmas

After the outbreak of the English Civil War the Parliamentary authorities shared the view of the Puritans that Christmas social activities threatened Christian beliefs and encouraged immoral behaviour. On 19 December 1643, an ordinance was passed encouraging subjects to treat the mid-winter period "with the more solemn humiliation because it may call to remembrance our sins, and the sins of our forefathers, who have turned this feast, pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him, by giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights". The rejection of Christmas as a joyful period was reiterated when a 1644 ordinance confirmed the abolition of the feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun.

In January 1645, Parliament produced a new Directory for Public Worship that made clear that festival days, including Christmas, were not to be celebrated but sent in respectful contemplation. From this point until the Restoration in 1660, Christmas was officially illegal. Although Cromwell himself did not initiate the banning of Christmas, his rise to power certainly resulted in the promotion of measures that severely curtailed such celebrations.

New Model Army

At the beginning of the war, Parliament relied on soldiers recruited by large landowners who supported their cause. Oliver Cromwell soon realised that these soldiers would not be good enough to defeat the Cavaliers. He pointed out in a letter to his cousin, John Hampden, about his regiment: "Your troopers are most of them old decayed serving men... the royalists' troopers are gentleman's sons, younger sons, persons of quality. Do you think that the spirits of such base and mean fellows will be ever able to encounter gentleman that have honour, courage and resolution in them? You must get men of a spirit... that is likely to go on as far as a gentleman will go, or else I am sure you will be beaten still." (41)

Cromwell recruited men who shared his "Puritan religious zeal". He also imposed strict discipline. When in April 1643, two troopers tried to desert, he had them whipped in the market place. Men who was heard to swear they would be fined "twelvepence; if he be drunk he is set in the stocks, or worse". Cromwell was careful about who he selected as officers. The Earl of Manchester complained that he did employ "men of estates" but "common men, poor and of mean parentage". He added that they were always very religious men. (42)

© National Portrait Gallery

Cromwell became convinced that some of the leaders of the Parliamentary Army were not committed to the destruction of the Royalist Army. He was a strong supporter of the Self-Denying Ordinance, where all peers and MP's should be removed from army and navy commands, including, Edward Montagu, the Earl of Manchester, Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex and Robert Rich, the Earl of Warwick and William Waller. At first, the House of Lords threw out the recommendation but with some changes it was eventually accepted. (43)

In February 1645, the House of Commons decided to form a new army of professional soldiers. This became known as the New Model Army. It was made up of ten cavalry regiments of 600 men each, twelve foot regiments of 1,200 men, and one regiment of 1,000 dragoons. General Thomas Fairfax, was appointed as its commander-in-chief. The new army contained a larger number of ideologically-committed soldiers and officers than any other army that had taken the field so far. Cromwell was quoted as saying: "I would rather have a plain russett-coated captain that know what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman and nothing else." (44)

Cromwell, as a MP, had to resign his command. However, a few weeks later, General Fairfax, gave him the rank of Lieutenant-General and he took charge of the cavalry. Members of the New Model Army received proper military training and by the time they went into battle they were very well-disciplined. In the past, people became officers because they came from powerful and wealthy families. In the New Model Army men were promoted when they showed themselves to be good soldiers. For the first time it became possible for working-class men to become army officers. Oliver Cromwell thought it was very important that soldiers believed strongly in what they were fighting for. Where possible he recruited men who, like him, held strong Puritan views and the New Model Army went into battle singing psalms, convinced that God was on their side. (45)

© National Portrait Gallery

The New Model Army took part in its first major battle just outside the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire on 14 June 1645. The battle began when Prince Rupert led a charge against the left wing of the parliamentary cavalry which scattered and Rupert's men then gave chase. While this was going on Cromwell launched an attack on the left wing of the royalist cavalry. This was also successful and the royalists that survived the initial charge fled from the battlefield. While some of Cromwell's cavalry gave chase, the majority were ordered to attack the now unprotected flanks of the infantry. Charles I was waiting with 1,200 men in reserve. Instead of ordering them forward to help his infantry he decided to retreat. Without support from the cavalry, the royalist infantry realised their task was impossible and surrendered. (46)

The battle was a disaster for the king. His infantry had been destroyed and 5,000 of his men, together with 500 officers, had been captured. The Parliamentary forces were also able to capture the Royalist baggage train that contained his complete stock of guns and ammunition. The women of the royalist camp were treated with great cruelty; those from Ireland were killed, while those from England had their faces slashed with daggers. Cromwell said after the battle that "this is none other than the hand of God, and to Him alone belongs the glory". (47)

Followed a series of defeats for the royalists, Charles I surrendered to the Scottish Presbyterian army besieging Newark, and was taken northwards to Newcastle upon Tyne. After nine months of negotiations, the Scots finally arrived at an agreement with Parliament and in exchange for £400,000, Charles was delivered to the parliamentary commissioners in January 1647. (48)

Oliver Cromwell and the Levellers

Parliament had become concerned about the activities of the Levellers during the English Civil War. In 1647 they organised a petition demanding reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (49)

There leaders, including John Lilburne, Richard Overton and William Walwyn were imprisoned. While in Newgate Prison, Lilburne used his time studying books on law and writing pamphlets. This included The Free Man's Freedom Vindicated (1647) where he argued that "no man should be punished or persecuted... for preaching or publishing his opinion on religion". He also outlined his political philosophy: "All and every particular and individual man and woman, that ever breathed in the world, are by nature all equal and alike in their power, dignity, authority and majesty, none of them having (by nature) any authority, dominion or magisterial power one over or above another." (50) In another pamphlet, Rash Oaths (1647), he argued: "Every free man of England, poor as well as rich, should have a vote in choosing those that are to make the law." (51)

The views of the Levellers had an impact on the New Model Army. On 28th October, 1647, members of the army began to discuss their grievances at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, but moved to the nearby lodgings of Thomas Grosvenor, Quartermaster General of Foot, the following day. This became known as the Putney Debates. The speeches were taken down in shorthand and written up later. As one historian has pointed out: "They are perhaps the nearest we shall ever get to oral history of the seventeenth century and have that spontaneous quality of men speaking their minds about the things they hold dear, not for effect or for posterity, but to achieve immediate ends." (52)

Thomas Rainsborough, the most radical of the officers, argued: "I desire that those that had engaged in it should speak, for really I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest he; and therefore truly. Sir, I think it's clear that every man that is to live under a Government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that Government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that Government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under; and I am confident that when I have heard the reasons against it, something will be said to answer those reasons, in so much that I should doubt whether he was an Englishman or no that should doubt of these things." (53)

John Wildman supported Rainsborough and dated people's problems to the Norman Conquest: "Our case is to be considered thus, that we have been under slavery. That's acknowledged by all. Our very laws were made by our Conquerors... We are now engaged for our freedom. That's the end of Parliament, to legislate according to the just ends of government, not simply to maintain what is already established. Every person in England hath as clear a right to elect his Representative as the greatest person in England. I conceive that's the undeniable maxim of government: that all government is in the free consent of the people." (54)

Edward Sexby was another who supported the idea of increasing the franchise: "We have engaged in this kingdom and ventured our lives, and it was all for this: to recover our birthrights and privileges as Englishmen - and by the arguments urged there is none. There are many thousands of us soldiers that have ventured our lives; we have had little property in this kingdom as to our estates, yet we had a birthright. But it seems now except a man hath a fixed estate in this kingdom, he hath no right in this kingdom. I wonder we were so much deceived. If we had not a right to the kingdom, we were mere mercenary soldiers. There are many in my condition, that have as good a condition, it may be little estate they have at present, and yet they have as much a right as those two (Cromwell and Ireton) who are their lawgivers, as any in this place. I shall tell you in a word my resolution. I am resolved to give my birthright to none. Whatsoever may come in the way, and be thought, I will give it to none. I think the poor and meaner of this kingdom (I speak as in that relation in which we are) have been the means of the preservation of this kingdom." (55)

These ideas were opposed by most of the senior officers in the New Model Army, who represented the interests of property owners. One of them, Henry Ireton, argued: "I think that no person hath a right to an interest or share in the disposing of the affairs of the kingdom, and indetermining or choosing those that determine what laws we shall be ruled by here - no person hath a right to this, that hath not a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom... First, the thing itself (universal suffrage) were dangerous if it were settled to destroy property. But I say that the principle that leads to this is destructive to property; for by the same reason that you will alter this Constitution merely that there's a greater Constitution by nature - by the same reason, by the law of nature, there is a greater liberty to the use of other men's goods which that property bars you." (56)

A compromise was eventually agreed that the vote would be granted to all men except alms-takers and servants and the Putney Debates came to an end on 8th November, 1647. The agreement was never put before the House of Commons. Leaders of the Leveller movement, including John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and John Wildman, were arrested and their pamphlets were burnt in public. (57)

Oliver Cromwell made it very clear that he very much opposed to the idea that more people should be allowed to vote in elections and that the Levellers posed a serious threat to the upper classes: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces." (58)

Execution of Charles I

Parliament initially held Charles under house arrest at Holdenby House in Northamptonshire. Members of the House of Commons had different opinions about what to do with Charles. Some like Denzil Holles were willing to accept the return of the king to power on minimal terms, whereas Puritans like Oliver Cromwell demanded that Charles agree to firm limitations on his power before the army was disbanded. They also were committed to the idea that each congregation should be able to decide its own form of worship. (59)

The New Model Army, frustrated by this lack of agreement, took Charles prisoner, and he was taken to Hampton Court Palace. Cromwell visited the king and proposed a deal. He would be willing to restore him as King and the Church of England as the official Church, if Charles and the Anglicans would agree to grant religious toleration. Charles rejected Cromwell's proposals and instead entered into a secret agreement with forces in Scotland who wanted to impose Presbyterianism. (60)

Charles escaped from captivity on 11th November, 1647, and made contact with Colonel Robert Hammond, Parliamentary Governor of the Isle of Wight, whom he apparently believed to be sympathetic. Hammond, however, arrested Charles in Carisbrooke Castle. In the early months of 1648 rebellions broke out in several parts of the country. Oliver Cromwell put down the Welsh rising and Thomas Fairfax dealt with the rebels in Kent and Surrey. (61)

In August 1648 Cromwell's parliamentary army defeated the Scots and once again Charles was taken prisoner. Parliament resumed negotiations with the King. The Presbyterians, the majority in the House of Commons, still hoped that Charles would save them from those advocating religious toleration and an extension of democracy. On 5th December, the House of Commons voted by 129 to 83 votes, to continue negotiations. The following day the New Model Army occupied London and Colonel Thomas Pride purged Parliament of MPs who favoured a negotiated settlement with the King . (62)

General Henry Ireton demanded that Charles was put on trial. Cromwell had doubts about this and it was not until several weeks later that he told the House of Commons that "the providence of God hath cast this upon us". Once the decision had been made Cromwell "threw himself into it with the vigour he always showed when his mind was made up, when God had spoken". (63)

In January 1649, Charles was charged with "waging war on Parliament." It was claimed that he was responsible for "all the murders, burnings, damages and mischiefs to the nation" in the English Civil War. The jury included members of Parliament, army officers and large landowners. Some of the 135 people chosen as jurors did not turn up for the trial. For example. General Thomas Fairfax, the leader of the Parliamentary Army, did not appear. When his name was called, a masked lady believed to be his wife, shouted out, "He has more wit than to be here." (64)

This was the first time in English history that a king had been put on trial. Charles believed that he was God's representative on earth and therefore no court of law had any right to pass judgement on him. Charles therefore refused to defend himself against the charges put forward by Parliament. Charles pointed out that on 6th December 1648, the army had expelled several members of' Parliament. Therefore, Charles argued, Parliament had no legal authority to arrange his trial. The arguments about the courts legal authority to try Charles went on for several days. Eventually, on 27th January, Charles was given his last opportunity to defend himself against the charges. When he refused he was sentenced to death. His death warrant was signed by the fifty-nine jurors who were in attendance. (65)

On the 30th January, 1649, Charles was taken to a scaffold built outside Whitehall Palace. Charles wore two shirts as he was worried that if he shivered in the cold people would think he was afraid of dying. He told his servant "were I to shake through cold, my enemies would attribute it to fear." Troopers on horseback kept the crowds some distance from the scaffold, and it is unlikely that many people heard the speech that he made just before his head was cut off with an axe. The executioner then took up the head and announced, in traditional fashion, "Behold the head of a traitor!" At that moment, according to an eyewitness, "there was such a groan by the thousands then present, as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again." (66)

The Commonwealth

The House of Commons now passed a series of new laws. They abolished the monarchy, on the grounds that it was "unnecessary, burdensome and dangerous to the liberty, safety and public interest of the people" and the House of Lords as "it is useless and dangerous to the people of England". Lands owned by the royal family and the church were sold and the money was used to pay the parliamentary soldiers. People were no longer fined for not attending their local church. However, everyone was still expected to attend some form of religious worship on Sundays. The country was now declared to be a "Commonwealth and Free State" under the rule of Parliament, and the government was entrusted to a Council of State, under the provisional chairmanship of Oliver Cromwell. (67)

The Levellers wanted Parliament to pass reforms that would increase universal suffrage. Soldiers also continued to protest against the government. The most serious rebellion took place in London. Troops commanded by Colonel Edward Whalley were ordered from the capital to Essex. A group of soldiers led by Robert Lockyer, refused to go and barricaded themselves in The Bull Inn near Bishopsgate, a radical meeting place. A large number of troops were sent to the scene and the men were forced to surrender. The commander-in-chief, General Thomas Fairfax, ordered Lockyer to be executed.

Lockyer's funeral on Sunday 29th April, 1649, proved to be a dramatic reminder of the strength of the Leveller organization in London. "Starting from Smithfield in the afternoon, the procession wound slowly through the heart of the City, and then back to Moorfields for the interment in New Churchyard. Led by six trumpeters, about 4000 people reportedly accompanied the corpse. Many wore ribbons - black for mourning and sea-green to publicize their Leveller allegiance. A company of women brought up the rear, testimony to the active female involvement in the Leveller movement. If the reports can be believed there were more mourners for Trooper Lockyer than there had been for the martyred Colonel Thomas Rainsborough the previous autumn." (68)

John Lilburne continued to campaign against the rule of Oliver Cromwell. According to a Royalist newspaper at the time: "He (Cromwell) and the Levellers can as soon combine as fire and water... The Levellers aim being at pure democracy.... and the design of Cromwell and his grandees for an oligarchy in the hands of himself." (69) Lilburne argued that Cromwell's government was mounting a propaganda campaign against the Levellers and to prevent them from replying their writings were censored: "To prevent the opportunity to lay open their treacheries and hypocrisies... the stop the press... They blast us with all the scandals and false reports their wit or malice could invent against us... By these arts are they now fastened in their powers." (70)

David Petegorsky, the author of Left-Wing Democracy in the English Civil War (1940) has pointed out: "The Levellers clearly saw, that equality must replace privilege as the dominant theme of social relationships; for a State that is divided into rich and poor, or a system that excludes certain classes from privileges it confers on others, violates that equality to which every individual has a natural claim." (71)

In May 1649 another Leveller-inspired mutiny broke out at Salisbury. Led by Captain William Thompson, they were defeated by a large army at Burford led by Major Thomas Harrison. Thompson escaped only to be killed a few days later near the Diggers community at Wellingborough. After being imprisoned in Burford Church with the other mutineers, three other leaders, "Private Church, Corporal Perkins and Cornett Thompson", were executed by Cromwell's forces in the churchyard. (72) John Lilburne responded by describing Harrison as a "hypocrite" for his initial encouragement of the Levellers. (73)

Ireland

Oliver Cromwell was asked by Parliament to take control of Ireland. The country had caused serious problems for English generals in the past so Cromwell was careful to make painstaking preparations before he left. Cromwell ensured that the wage arrears of his army were paid, and that he was guaranteed sufficient financial provision by parliament. On 15th August 1649, Cromwell arrived in Ireland and took control of an army of 12,000 men. (74) Cromwell made a speech to the Irish people the following day: "God has brought us here in safety... We are here to carry on the great work against the barbarous and blood-thirsty Irish... to propagate the Gospel of Christ and the establishment of truth... and to restore this nation to its former happiness and tranquility." (75)

Cromwell, like nearly all Puritans "had been inflamed against the Irish Catholics by the true and false allegations of the atrocities which they had committed against English Protestants settlers during the Irish Catholic rebellion of 1641." (76) He wrote at the time that "all the world knows their barbarism". Even the philosopher, Francis Bacon, and the poet John Milton, who "believed passionately in liberty and human dignity", shared the view that "the Irish were culturally so inferior that their subordination was natural and necessary." (77)

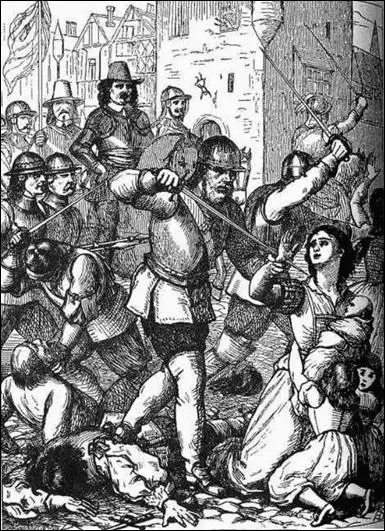

Cromwell's first action on reaching Ireland was to forbid any plunder or pillage - an order that could not have been enforced with an unpaid army. Two men were hanged for plundering to convince the soldiers he was serious about this order. To control Dublin's northern approaches Cromwell needed to take the port of Drogheda. Once in his hands he could feel confident of controlling the whole of the northern route from Dublin to Londonderry. On 3rd September, around 12,000 men and supporting vessels had arrived outside the town. Surrounding the whole town was a massive wall, 22 feet high and 6 feet thick.

Sir Arthur Aston, who had been fighting for the royalists during the English Civil War, was the governor of Drogheda. On 10th September, Cromwell advised Aston to surrender. "I have brought the army belonging to the Parliament of England to this place, to reduce it to obedience... if you surrender you will avoid the loss of blood... If you refuse... you will have no cause to blame me." (78)

Cromwell had four times as many men as Aston and was better supplied with weapons, stores and equipment. Cromwell's proposal was rejected and the garrison opened fire with what weapons they had. Cromwell's reply was to attack the city wall and by nightfall two breaches had been made. The following day Cromwell led his soldiers into Drogheda.

Aston and some 300 soldiers climbed Mill Mount. Cromwell's troops surrounded the men and it was usually the custom to allow them to surrender. However, Cromwell gave the order to kill them all. Aston's head was beaten in with his own wooden leg. Cromwell instructed his men to kill all the soldiers in the town. About eighty men had taken refuge in St Peter's Church. It was set on fire and all the men were killed. All the priests that were captured were also slaughtered. (79)

Cromwell sent a letter to William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons: "I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbued their hands in so much innocent blood; and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are the satisfactory grounds for such actions, which otherwise cannot but work remorse and regret." (80)

The response from Parliament was that they were unwilling to pay for a long war. He was told to take control of the large estates owned by Catholics and to sell or rent it to Protestants. This money was to be used to pay his soldiers. Cromwell decided that the best way to bring a quick end to the war was to carry out another massacre. After an eight days' siege at Wexford, around 1,800 troops, priests and civilians were butchered. (81)

Hugh Peter, a chaplain to the Parliamentary army and a passionate anti-Catholic, was with Cromwell in Ireland. He reported that the town was now available for English Protestant colonists to settle. "It is a fine spot for some godly congregation, where house and land wait for inhabitants and occupiers." (82)

During the next few years of bloodshed it is estimated that about a third of the population was either killed or died of starvation. The majority of Roman Catholics who owned land had it taken away from them and were removed to the barren province of Connacht. Catholic boys and girls were shipped to Barbados and sold to the planters as slaves. The land taken from the Catholics by Cromwell was given to the Protestant soldiers who had taken part in the campaign. Before the rebellion in 1641, Catholics owned 59% of the land in Ireland. By the time Cromwell left in 1650 the proportion had shrunk to 22%. (83)

Oliver Cromwell and the Radicals

On 9th March, 1649, the House of Lords was abolished. (84) Although the House of Commons continued to meet, it was Cromwell and his followers who controlled England. The Levellers continued to campaign for an increase in the number of people who could vote. John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and Thomas Prince, all served terms of imprisonment. On 20th September, 1649, Parliament passed a law introducing government censorship. It now required a licence for the publication of any book, pamphlet, treatise or sheets of news. As Pauline Gregg has pointed out that the situation was little different "from the censorship they had been fighting in the King's time". (85)

On 24th October, 1649, Lilburne was charged with high treason. The trial began the following day. The prosecution read out extracts from Lilburne's pamphlets but the jury was not convinced and he was found not guilty. There were great celebrations outside the court and his acquittal was marked with bonfires. A medal was struck in his honour, inscribed with the words: "John Lilburne saved by the power of the Lord and the integrity of the jury who are judge of law as well of fact". On 8th November, all four men were released. (86)

Cromwell was also having problems with Gerrard Winstanley, the leader of the group that became known as the Diggers. Winstanley began arguing that all land belonged to the community rather than to separate individuals. In January, 1649, he published the The New Law of Righteousness. In the pamphlet he wrote: "In the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another." (87)

Winstanley claimed that the scriptures threatened "misery to rich men" and that they "shall be turned out of all, and their riches given to a people that will bring forth better fruit, and such as they have oppressed shall inherit the land." He did not only blame the wealthy for this situation. As John Gurney has pointed out, Winstanley argued: "The poor should not just be seen as an object of pity, for the part they played in upholding the curse had also to be addressed. Private property, and the poverty, inequality and exploitation attendant upon it, was, like the corruption of religion, kept in being not only by the rich but also by those who worked for them." (88)

Winstanley claimed that God would punish the poor if they did not take action: "Therefore you dust of the earth, that are trod under foot, you poor people, that makes both scholars and rich men, your oppressors by your labours... If you labour the earth, and work for others that live at ease, and follows the ways of the flesh by your labours, eating the bread which you get by the sweat of your brows, not their own. Know this, that the hand of the Lord shall break out upon such hireling labourer, and you shall perish with the covetous rich man." (89)

On Sunday 1st April, 1649, Winstanley, William Everard, and a small group of about 30 or 40 men and women started digging and sowing vegetables on the wasteland of St George's Hill in the parish of Walton. They were mainly labouring men and their families, and they confidently hoped that five thousand others would join them. (90) They sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots, and beans. They also stated that they "intended to plough up the ground and sow it with seed corn". (91) Research shows that new people joined the community over the next few months. Most of these were local inhabitants. (92)

Local landowners were very disturbed by these developments. According to one historian, John F. Harrison: "They were repeatedly attacked and beaten; their crops were uprooted, their tools destroyed, and their rough houses." (93) Oliver Cromwell condemned the actions of the Diggers: "What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces." (94)

Instructions were given for the Diggers to be beaten up and for their houses, crops and tools to be destroyed. These tactics were successful and within a year all the Digger communities in England had been wiped out. A number of Diggers were indicted at the Surrey quarter sessions and five were imprisoned for just over a month in the White Lion prison in Southwark. (95)

© National Portrait Gallery

Cromwell also had problems with the Ranters. In 1650 Abiezer Coppe published A Fiery Flying Roll: A Word from the Lord to all the great ones of the Earth. In this pamphlet he claimed that "the Levellers (men-levellers) which is and who indeed are but shadows of most terrible, yet great and glorious good things to come". People who did not own property would have "treasure in heaven". His main message was that God, the "mighty leveller" would return to earth and punish those who did not share their wealth. Coppe argued for freedom, equality, community and universal peace. He told the wealthy that they would be punished for their lack of charity towards the poor: "The rust of your silver, I say, shall eat your flesh as it were fire... have... Howl, howl, ye nobles, howl honourable, howl ye rich men for the miseries that are coming upon you." (96) The historian, Alfred Leslie Rowse, claims that Coppe's "egalitarian Communism" was "300 years" before its time. (97)

Laurence Clarkson, had been a preacher in the New Model Army who wrote a pamphlet he defined the "oppressors" as the "nobility and gentry" and the oppressed as the "yeoman farmer" and the "tradesman". (98) Coppe and Clarkson both advocated "free love". (99) Peter Ackroyd claimed that Coppe and Clarkson professed that "sin had its conception only in imagination" and told their followers that they "might swear, drink, smoke and have sex with impunity". (100)

Barry Coward, the author of The Stuart Age: England 1603-1714 (1980) argues that the activities of the Ranters created a "moral panic" because their activities were "often violent and anti-social" and frightened conservative opinion into reaction. They formed a "hippy-like counter culture of the 1650s which flew in the face of law and morality and which was considered with horror by respectable society." (101) Cromwell disliked the Ranters more than any other religious sect who he considered to be totally immoral. (102)

Cromwell and his supporters in Parliament attempted to deal with preachers such as Coppe and Clarkson, by passing the Adultery Act (May 1650), that imposed the death penalty for adultery and fornication. This was followed by the Blasphemy Act (August 1650). Coppe claimed he had been informed that the acts against adultery and blasphemy "were put out because of me; thereby secretly intimating that I was guilty of the breach of them". (103) Christopher Hill, the author of The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1991), agrees that this legislation was an attempt to deal with the development of religious groups such as the Ranters. (104)

Lord Protector

Oliver Cromwell became increasingly frustrated by the inability of Parliament to get anything done. His biographer, Pauline Gregg, has pointed out: "He realized that all revolutions are about power and he was asking himself who, or what, should exercise that power. He knew, moreover, that whoever or whatever was in control must be strong enough to propel the state in one direction. This he learned from his battle experience. To be successful an army must observe one plan, one directive." (105)

Major General Thomas Harrison, who had been sympathetic to the demands of the Levellers, urged the House of Commons to pass legislation to help the poor. In August 1652, he promoted an army petition that called for law reform, the more effective propagation of the gospel, the elimination of tithes, and speedy elections for a new parliament. When it failed to act on these items, Harrison began to press for its dissolution. Harrison argued that when it was established after the death of the Charles I it was "unanimous in its proceedings for the reform of the nation" but it was now dominated by "a strong Royalist party". (106)

On 20th April 1653, Cromwell sent in his troopers with their muskets and drawn swords into the House of Commons. Harrison himself pulled the Speaker, William Lenthall, out of the Chair and pushed him out of the Chamber. That afternoon Cromwell dissolved the Council of State and replaced it with a committee of thirteen army officers. Harrison was appointed as chairman and in effect the head of the English state. (107)

In July, 1653, Oliver Cromwell established the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints. The total number of nominees was 140, 129 from England, five from Scotland and six from Ireland. The nominated assembly grappled with several of Harrison's favourite issues, including the immediate abolition of tithes. There was general consensus that tithes were objectionable, but no agreement about what mechanism for generating revenue should replace them. (108)

The Parliament was closed down by Cromwell in December, 1653. Charles H. Simpkinson has argued that Harrison now believed that "England now lay under a military despotism". (109) This decision was fiercely opposed by Thomas Harrison. Cromwell reacted by depriving him of his military commission, and in February, 1654, he was ordered to retire to Staffordshire. However, he was able to keep the land he had acquired during his period of power. The total value of this land was well over £13,000. (110)

The army decided that Oliver Cromwell should become England's new ruler. Some officers wanted him to become king but he refused and instead took the title Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. However, Cromwell had as much power as kings had in the past. The franchise was restricted to those who possessed the very high property qualification of £200 and by the disqualification of all who had taken part in the English Civil War on the royalist side. (111)

When the House of Commons opposed his policies in January 1655, he closed it down. Cromwell always disliked the idea of democracy as he posed a threat to good government. "The mass of the population was totally unsophisticated politically, very much under the influence of landlords and parsons: to give such men the vote (with no secret ballot, since most of them were illiterate) would be to strengthen rather than to weaken the power of the conservatives." (112)

Richard Baxter attempted to explain Cromwell's thinking: "In most parts, the major vote of the vulgar... is ruled by money and therefore by their landlords." (113) Cromwell warned Parliament that the vast majority of the population was opposed to his government: "The condition of the people is such as the major part a great deal are persons disaffected and engaged against us." (114) One pamphlet published at the time commented "if the common vote of the giddy multitude must rule the whole" Cromwell's government would be overthrown. (115)

Cromwell now imposed military rule. England was divided into eleven districts. Each district was run by a Major General and were answerable only to the Lord Protector. Christopher Hill argues that "The Major-Generals were to make all men responsible for the good behaviour of their servants.... They also enforced the legislation of the Long Parliament against drunkenness, blasphemy and sabbath-breaking... Above all they took control of the militia, the army of the gentry." (116)

The first duty of the Major-Generals was to maintain security by suppressing unlawful assemblies, disarming Royalist supporters and apprehending thieves, robbers and highwaymen. The militia of the Major-Generals was funded by a new 10% income tax imposed on Royalists known as the "decimation tax". It was argued that a punitive tax on Royalists was a just means of financing the militia because Royalist conspiracies had made it necessary in the first place. (117)

The responsibilities of these Major-Generals included granting poor relief and imposing Puritan morality. In some districts bear-baiting, cock-fighting, horse-racing and wrestling were banned. Betting and gambling were also forbidden. Large numbers of ale-houses were closed and fines were imposed on people caught swearing. In some districts, the Major-Generals even closed down theatres. (118)

Former members of the Levellers grew disillusioned with the dictatorial policies of Cromwell and in 1655 Edward Sexby, John Wildman and Richard Overton were involved in developing a plot to overthrow the government. The conspiracy was discovered and the men were forced to flee to the Netherlands. It was later argued that Overton was by this time acting as a double agent and had informed the authorities of the plot. (119) Records show that Overton was receiving payments from Cromwell's secretary of state, John Thurloe. (120)

In May 1657 Sexby published, under a pseudonym, Killing No Murder, a pamphlet that attempted to justify the assassination of Oliver Cromwell. Sexby accused Cromwell of the enslavement of the English people and argued for that reason he deserved to die. After his death "religion would be restored" and "liberty asserted". He hoped "that other laws will have place besides those of the sword, and that justice shall be otherwise defined than the will and pleasure of the strongest". (121) The following month Edward Sexby arrived in England to carry out the deed, however, he was arrested on 24th July. He remained in the Tower of London until his death on 13th January 1658. (122)

In 1658 Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard Cromwell, to replace him as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. The English army was unhappy with this decision. While they respected Oliver as a skillful military commander, Richard was just a country farmer. To help him Cromwell brought him onto the Council to familiarize him with affairs of state. (123)

Oliver Cromwell died on 3rd September 1658. Richard Cromwell became Lord Protector but he was bullied by conservative MPs into support measures to restrict religious toleration and the army's freedom to indulge in political activity. The army responded by forcing Richard to dissolve Parliament on 21st April, 1659. The following month he agreed to retire from government. (124)

Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monk, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army to London. According to Hyman Fagan: "Faced with a threatened revolt, the upper classes decided to restore the monarchy which, they thought, would bring stability to the country. The army again intervened in politics, but this time it opposed the Commonwealth". (125)

Monck reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. Monck now contacted Charles, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an 'absolute' monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s. (126)

Despite this agreement a special court was appointed and in October 1660 those Regicides who were still alive and living in Britain were brought to trial. Ten were found guilty and were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. This included Thomas Harrison, John Jones, John Carew and Hugh Peters. Others executed included Adrian Scroope, Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Francis Hacker, Daniel Axtel and John Cook. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (127)

Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, Thomas Pride and John Bradshaw were all posthumously tried for high treason. They were found guilty and on the twelfth anniversary of the regicide, on 30th January 1661, their bodies were disinterred and hung from the gallows at Tyburn. (128) Cromwell's body was put into a lime-pit below the gallows and the head, impaled on a spike, was exposed at the south end of Westminster Hall for nearly twenty years. (129)

Primary Sources

(1) Sir Philip Warwick, a Royalist, made these comments on Oliver Cromwell in about 1640.

He wore... a plain cloth-suit, which seemed to have been made by a poor tailor; his shirt was plain, and not very clean; and I remember a speck or two of blood upon his collar... his face was swollen and red, his voice sharp and untunable, and his speech full of passion.

(2) Oliver Cromwell, speech to the people of Dublin after his arrival in Ireland (16 August, 1649)

God has brought us here in safety... We are here to carry on the great work against the barbarous and blood-thirsty Irish... to propagate the Gospel of Christ and the establishment of truth... and to restore this nation to its former happiness and tranquillity.

(3) Earl of Clarendon wrote about Oliver Cromwell in his book History of the Rebellion (c. 1688)

Without doubt, no man with more wickedness ever brought to pass what he desired more wickedly.

(4) John Lilburne was a Leveller who was imprisoned by Oliver Cromwell. In 1649 Lilburne wrote a letter to Cromwell.

We have much cause to distrust you; for we know how many broken promises that you have made to the kingdom.

(5) In about 1660, Edward Burrough, a Quaker, wrote down his thoughts on Oliver Cromwell.

He loved the praise of men, and took flattering titles... He allowed tithes and false worship and other popish stuff.... He persecuted and imprisoned people for criticising things that were popish.

(6) Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary these comments on Oliver Cromwell in July 1667.

Everybody do nowadays reflect upon Cromwell and praise him... what brave things he did and made all the foreign princes fear him.

(7) Nathaniel Crouch, A History of Oliver Cromwell (1692)

Many people in our times... have a great respect for the memory of Oliver Cromwell, as being a man of devout religion and a great champion for the liberties of the nation.

(8) Richard Overton, Hunting the Foxes (March, 1649)

O Cromwell, O Ireton, how hath a little time and success changed the honest shape of so many officers! Who then would have thought the army council would have moved for an act to put men to death for petitioning? Who would have thought to have seen soldiers (by their order) to ride with their faces towards their horse tails, to have their swords broken over their heads, and to be cashiered, and that for petitioning, and claiming their just right and title to the same?

Was there ever a generation of men so apostate so false and so perjured as these? Did ever men pretend an higher degree of holiness, religion, and zeal to God and their country than these? These preach, these fast, these pray, these have nothing more frequent than the sentences of sacred scripture, the name of God and of Christ in their mouths: you shall scarce speak to Cromwell about anything, but he will lay his hand on his breast, elevate his eyes, and call God to record, he will weep, howl and repent, even while he doth smite you under the first rib.

(9) Oliver Cromwell, writing to the Speaker of the House of Commons after defeating the Catholics at Drogheda. (September, 1649)

Every tenth man of the soldiers were killed and the rest sent to the Barbados... I think we put to the sword altogether about 2,000 men... about 100 of them fled to St Peter's Church... they asked for mercy, I refused... I ordered St Peter's Church to be set on fire.

(10) Message sent by Oliver Cromwell to Sir Arthur Aston, commander of the Irish forces in Drogheda (10th September, 1649)

I have brought the army belonging to the Parliament of England to this place, to reduce it to obedience... if you surrender you will avoid the loss of blood... If you refuse... you will have no cause to blame me.

(11) Oliver Cromwell commenting on the activities of the Levellers and the Diggers (1649)

What is the purport of the levelling principle but to make the tenant as liberal a fortune as the landlord. I was by birth a gentleman. You must cut these people in pieces or they will cut you in pieces.

(12) Edward Sexby, Killing No Murder (1657)

To his Highness, Oliver Cromwell. To your Highness justly belongs the Honour of dying for the people, and it cannot choose but be unspeakable consolation to you in the last moments of your life to consider with how much benefit to the world you are like to leave it. 'Tis then only (my Lord) the titles you now usurp, will be truly yours; you will then be indeed the deliverer of your country, and free it from a bondage little inferior to that from which Moses delivered his. You will then be that true reformer which you would be thought. Religion shall be then restored, liberty asserted and Parliaments have those privileges they have fought for. We shall then hope that other laws will have place besides those of the sword, and that justice shall be otherwise defined than the will and pleasure of the strongest; and we shall then hope men will keep oaths again, and not have the necessity of being false and perfidious to preserve themselves, and be like their rulers. All this we hope from your Highness's happy expiration, who are the true father of your country; for while you live we can call nothing ours, and it is from your death that we hope for our inheritances. Let this consideration arm and fortify your Highness's mind against the fears of death and the terrors of your evil conscience, that the good you will do by your death will something balance the evils of your life.

Student Activities

Portraits of Oliver Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Oliver Cromwell in Ireland (Answer Commentary)

John Lilburne and Parliamentary Reform (Answer Commentary)

Gerrard Winstanley the Failed Digger Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Military Tactics in the Civil War (Answer Commentary)