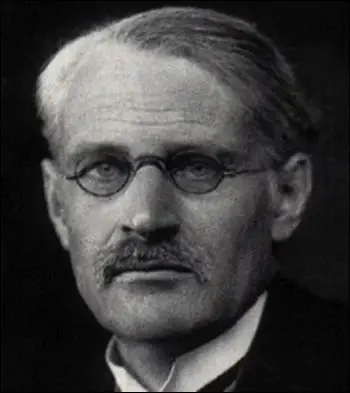

George Macaulay Trevelyan

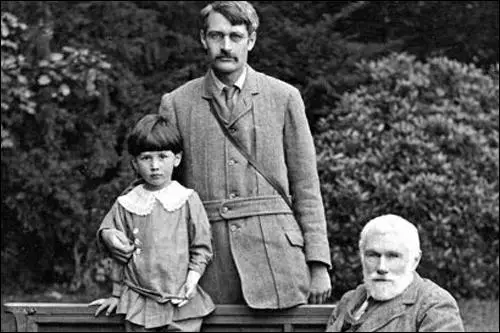

George Macaulay Trevelyan, the son of the Liberal politician, George Otto Trevelyan, was born in Stratford-on-Avon on 16th February, 1876. His grandfather Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan was a reforming civil servant. His mother, Caroline Philips, was the daughter of Robert Needham Philips, who was also a member of the House of Commons. (1)

George had two brothers, Charles Trevelyan and Robert Trevelyan. He later claimed that their childhood was very political. He described how "a sense of drama of English and Irish history was purveyed to me through daily sights and experiences, with my father as commentator and bard." (2)

The three boys spent a lot of time playing with their toy soldiers where they replayed famous battles. "Much of our pocket money must have gone towards purchasing those exquisitely packed cardboard boxes, each containing twenty or thirty infantrymen... all moulded, packed and painted at Nuremberg. Even now I sometimes dream of discovering and pillaging marvellous magic toy shops, rich with countless boxes of the oldest and best soldiers, and most precious of all, artillery - canon, gunners." (3)

At an early age he discovered his great-uncle was the historian, Thomas Babington Macaulay. She used to read him passages from his book, History of England. "I remember so well Mama reading it to me for the first time when I was a little boy; it was in the library, and I used to lie with my head on the woolly rug against the fire and look up at the marble head carved on the mantelpiece, while she read." (4)

George Macaulay Trevelyan

Trevelyan was educated at Harrow and Trinity College, where he studied history. He also developed a strong interest in literature and politics. He wrote to his mother that "I live in literature, politics and history, and am burning for the world (be it only Cambridge). (5)

Beatrice Webb met him for the first time in 1895: "He (George Macaulay Trevelyan) is bringing himself up to be a great man, is precise and methodical in all his ways, ascetic and regular in his habits, eating according to rule, exercising according to rule... he is always analysing his powers, and carefully considering how he can make the best of himself. In intellectual parts, he is brilliant, with a wonderful memory, keen analytical power, and a vivid style. in his philosophy of life, he is, at present, commonplace, but then he is young - only nineteen." (6)

While at the University of Cambridge was soon elected to the Apostles, the university's most exclusive and influential undergraduate society. Other members included Lytton Strachey, E. M. Forster, Roger Fry, Leonard Wolff, George Edward Moore, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson and Desmond MacCarthy. His contemporaries included John Maynard Keynes, Bertrand Russell and Ralph Vaughan Williams. (7)

George Macaulay Trevelyan was a puritan and strongly disapproved of the homosexuality of some of the Apostles. Strachey complained about his moral views: "Trevy... at once launched into lecture after lecture. It was truly awful. Everything he said was stupid and rude to such a painful degree! In addition to all the old ordinary horrors, he has now become curiously numb and dumb... I believe he's disappointed, almost embittered." (8)

Although he rejected homosexual relations that had became widespread for a time among some Apostles, he did absorb their culture of radical agnosticism. According to his biographer, David Cannadine, Trevelyan remained all his life loyal to a secular version of Christian ethics: "a love of things good, and a hatred of things evil". In 1896 he obtained a first in the historical tripos, and soon after he was elected a fellow of Trinity. (9)

Historian

In 1896 he obtained a first in the historical tripos, and soon after he was elected a fellow of Trinity College. The following year he completed his first book, England in the Age of Wycliffe (1899) that dealt with the Peasants' Revolt. Soon afterwards he gave up his fellowship. As he had a large private income he did not have to be a professional historian. Instead he was able to write his books independently. He also taught part-time at the Working Men's College in London. (10)

George Macaulay Trevelyan published England under the Stuarts in 1904. Cannadine has described the book as "an outstandingly successful general survey, which unfolded the familiar story of the civil war and the revolution of 1688 in more disciplined prose and mature style. As he interpreted it, the seventeenth century witnessed fundamental advances in religious toleration and parliamentary freedom, the forces of Catholic despotism were vanquished, and Great Britain gradually evolved towards the status of a world power". (11)

In 1904 he married Janet Penrose Ward, the daughter of the novelist Mary Augusta Ward and Thomas Humphry Ward, a journalist. She was the great niece of the poet Matthew Arnold, and the great granddaughter of Dr Thomas Arnold, the reforming headmaster of Rugby School. The couple moved to Cheyne Gardens in Chelsea and Janet had three children, Mary Caroline (1905), Theodore Macaulay (1906), who died from appendicitis in 1911, and Charles Humphry (1909).

George's brother, Charles Trevelyan, was adopted as the Liberal Party parliamentary candidate for North Lambeth, but was narrowly defeated in the 1895 General Election. The following year he argued that he was attracted to the philosophy of socialism. "I have the greatest sympathy with the growth of the socialist party. I think they understand the evils that surround us and hammer them into people's minds better than we Liberals. I want to see the Liberal party throw its heart and soul fearlessly into reform so as to prevent a reaction from the present state of thugs and the violent revolution that would inevitably follow it." (12)

Family influence enabled him to being adopted for the constituency of Elland, and entered parliament after a by-election in March 1899. Charles Trevelyan was a very independent member of the House of Commons and took George's advice: "It is a rule that no Trevelyan ever sucks up either to the press, or the chiefs, or the 'right people'. The world has given us money enough to enable us to do what we think is right. We thank it for that and ask no more of it, but to be allowed to serve it." (13)

George Macaulay Trevelyan was more interested in writing history than politics. According to David Cannadine: "His great work was his Garibaldi trilogy (1907–11), which established his reputation as the outstanding literary historian of his generation. It depicted Garibaldi as a Carlylean hero - poet, patriot, and man of action - whose inspired leadership created the Italian nation. For Trevelyan, Garibaldi was the champion of freedom, progress, and tolerance, who vanquished the despotism, reaction, and obscurantism of the Austrian empire and the Neapolitan monarchy. The books were also notable for their vivid evocation of landscape, for their innovative use of documentary and oral sources, and for their spirited accounts of battles and military campaigns." (14)

Garibaldi and the Making of Italy was published in September 1911 and sold 3,000 copies in a few days. John H. Plumb attempted to explain the success of the book. "These were the years of the greatest liberal victory in English politics for a generation. The intellectual world responded to the optimism of the politicians... The Garibaldi story fitted these moods." Plum went on to argue that Trevelyan wrote like a poet. "Having read (Trevelyan's work), who could doubt that here was a great artist at work; at work in a medium, the writing of history, in which scholars have been plentiful and artists rare. But why did Trevelyan choose to use his gift of imagination in history rather than poetry?" (15)

Other historians were not so impressed with Trevelyan's work. Stefan Collini argues that Trevelyan was a deeply flawed historian. "Trevelyan was able to write with an easy familiarity about the families who had for so long ruled England, and yet in some ways his inherited sense of his destiny was a handicap: there were certain kinds of questions it didn't dispose him to ask... he was not prompted to be critically reflective about the assumptions and concepts he brought to the writing of history. In an important sense, Trevelyan was not an intellectual." (16)

First World War

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, Charles Trevelyan, David Lloyd George, John Burns and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

The anti-war newspaper, The Daily News, commented: "Among the many reports which are current as to Ministerial resignations there seems to be little doubt in regard to three. They are those of Lord Morley, Mr. John Burns, and Mr. Charles Trevelyan. There will be widespread sympathy with the action they have taken. Whether men approve of that action or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... Mr. Trevelyan will find abundant work in keeping vital those ideals which are at the root of liberty and which are never so much in danger as in times of war and social disruption." (17)

In a letter to his constituents Charles Trevelyan explained his reasons for resignation: "However overwhelming the victory of our navy, our commerce will suffer terribly. In war too, the first productive energies of the whole people have to be devoted to armaments. Cannon are a poor industrial exchange for cotton. We shall suffer a steady impoverishment as the character of our work exchanges. All this I felt so strongly that I cannot count the cause adequate which is to lead to this misery. So I have resigned." (18)

At first George supported his brother's actions. Julian Huxley recalled that George "buried his head on his hands on the breakfast table, and looked up weeping". He told Huxley "millions of human beings are going to be killed in this senseless business". (19) However, once the war started, he reluctantly decided to support the war. This brought him into direct conflict with Charles Trevelyan. (20)

George wrote to Charles, three days after the war was declared: "I wish to see no-one crushed, neither France, Belgium nor Germany... So now that war has come, which I wish we had avoided, I support the war not merely from the point of view of our own survival but because I think German victory will probably be the worst thing for Europe, at any rate her victory in the West." (21)

A week later George wrote to Charles again. "You will be all the more effective for peace when the time comes if you show patriotism now and don't make yourselves widely unpopular... You have of all people made your position clear, and sacrificed for it... anything you can now do or say to show you are backing the war, as we are in it, will make you the more effective for peace when the time comes." (22)

Charles Trevelyan rejected this advice. As A. J. A. Morris has pointed out, it was clear to him that "Britain was condemned to war for no better reason than sentimental attachment to France and hatred of Germany. Trevelyan resigned from the government in protest. By this action he found himself estranged from most of his family, condemned and vilified by a hysterical press, and rejected by his constituency association." (23)

The Daily Sketch launched a personal attack on Trevelyan accusing him of being pro-German: "Trevelyan would then have a very congenial atmosphere - in the Reichstag. We have no time to listen to his foolish and pernicious talk. It is a scandal that he should be in Parliament when he continues to preach these pro-German and utterly impracticable pacifist doctrines. Trevelyan must go". (24)

George Macaulay Trevelyan was also highly critical of his brother. "I know that wisdom may begin to come to poor human beings through misery. But even I doubt when I see people like George carried away by shallow fears and ill-informed hatreds... It shows how absurdly far we are from brotherly feeling to foreigners when even in him it is a shallow veneer. He like all the rest wants to hate the Germans... I am more discouraged by it than anything else because it shows the helplessness of intellect before national passion." (25)

George Trevelyan supported the war effort as he was convinced that Kaiser Wilhelm II was a despot that needed to be defeated. His defective eyesight meant he was unfit for military service, and so in 1915 he became commandant of the first British Red Cross ambulance unit to be sent to Italy. He spent the next three years transporting wounded soldiers to hospitals behind the lines.

He explained his thoughts on the war in a letter he wrote to his father in May, 1917. "We are in the third day and night of the biggest battle we have had yet, and likely to be the most prolonged. It is a great pleasure to be in the fullness of activity and adventure day after day and night after night. Both in Gorizia and also in the high hills such scenes of beauty and romance as this big war in the mountains are wonderful indeed. It is a great life for me, rushing about from front to front and now and then to the base along this thirty miles of mountain battle. No one can have a pleasanter part in it." (26)

Liberalism to Conservatism

Trevelyan recorded his experiences in the First World War in Scenes from Italy's War (1919). The following year he finally completed his long awaited book on Earl Grey entitled Lord Grey of the Reform Bill (1920). This was followed by British History in the Nineteenth Century (1922) and Manin and the Venetian Revolution of 1848 (1923).

During this period he decided he would write a patriotic history of England. He told his father, George Otto Trevelyan: "In this age of democracy and patriotism, I feel strongly drawn to write the history of England as I feel it, for the people... The war has cleared my mind of some party prejudices or points of view and I feel as if I have a conception of the development of English history, liberal but purely English and embracing the other elements. It might be a success as a literary work (otherwise I would not touch it). The doubt in my mind is whether it could have elbow room to be a literary success without being so long as to prevent the wide popularity which would alone justify the choice of it." (27)

Trevelyan's highly popular, History of England, was published in 1926. This book took a less partisan view of politics than his earlier writings. "Trevelyan had resolved to write such a book during the First World War as a celebration of, and thank-offering to, the English people. In it he set out the essential elements of the nation's evolution and identity: parliamentary government, the rule of law, religious toleration, freedom from continental interference or involvement, and a global horizon of maritime supremacy and imperial expansion". (28)

Trevelyan's new political views were criticised by other historians. Geoffrey Elton denounced him as a "not very scholarly writer" who produced "soothing pap... lavishly doled out... to a large public". (29) John P. Kenyon complains that Trevelyan was an "insufferable snob" with "socially retrograde views". (30) J. C. D. Clark suggests that Trevelyan was guilty of "shallowness" and "superficiality". (31)

By this time he had abandoned the Liberal Party for the Conservative Party. Whereas his brother, Charles Trevelyan, was now a leading member of the Labour Party. The author of A Very British Family: The Trevelyans (2006) has claimed that "George's wartime adventures had changed him". (32) His biographer has argued that his history writing reflected a change in his political opinions: "Trevelyan had a very strong sense of national identity and he wrote his books in part because he had that sense of identity but he also wrote his books to promote that sense of national identity... He believed history had a social and political purpose and on the whole it was to reinforce a sense of identity and belonging rather than to subvert it." (33)

In 1927, Stanley Baldwin, the Conservative Prime Minister, appointed George Macaulay Trevelyan regis professor of modern history at University of Cambridge. Professional success was accompanied by personal wealth following the death of his parents in 1928. Charles inherited Wallington Hall whereas George became the owner of a large house and estate at Hallington Hall in Northumberland. "George used his considerable new-found wealth to buy up beautiful and historic places in England's threatened landscape." (34)

George Macaulay Trevelyan published a series of history books. This included Blenheim (1930), The Calls and Claims of Natural Beauty (1931), Ramillies and the Union with Scotland (1932), The Peace and the Protestant Succession (1934), Sir George Otto Trevelyan: A Memoir (1932), Grey of Fallodon (1937) and The English Revolution, 1688–1698 (1938).

The Second World War

In the 1930s Trevelyan became concerned about the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. But as a supporter of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain, he argued for appeasement: "Although he admired Winston Churchill as a writer and historian, he had no time for Churchill's views on India, Germany, or Edward VIII, and he was a firm supporter of the Munich settlement. But he had little doubt that another war with Germany would come, and that whatever the result, a second such conflict in his lifetime would spell the end of the world as he had known it." (35)

In October 1939, he wrote to his brother, Robert Trevelyan, about his feelings about the inevitable outbreak of the Second World War. "The last thing Edward Grey (the Foreign Secretary at the outbreak of the First World War) said to me in the few weeks between the Nazi revolution and his death was, 'I see no hope for the world'. There is less now. One half of me suffers horribly, the other half is detached, because the 'world' that is threatened is not my world, which died years ago. I am a mere survivor. Life has been a great gift for which I am grateful, though I would gladly give it back now." (36)

George Macaulay Trevelyan spent the early years of the war writing, English Social History: A Survey of Six Centuries. He told his daughter that he wanted to write a history of England that took into account the lives of our ancestors in a way that did not depend on "the well known names of Kings, Parliaments and wars", but instead moved "like an underground river, obeying its own laws or those of economic change, rather than following the direction of political happenings that move on the surface of life". (37)

The book could not be published in England until 1942, because of wartime paper shortages. After seven years it sold nearly 400,000 copies. John H. Plumb argued that the book appeared just at the right time: "The war... had jeopardized the traditional pattern of English life, and in some ways destroyed it forever. This created among all classes a deep nostalgia for the way of life which we were losing. Then, again, the war had made conscious to millions that our national attitude to life was historically based, the result of centuries of slow growth, and that it was for the old, tried ways of life for which we were fighting. Winston Churchill, in his great war speeches made us all conscious of our past, as never before. And in this war, too, there were far more highly educated men and women in all ranks of all the services. The twenties and thirties of this century had witnessed a great extension of secondary school education, producing a vast public capable of reading and enjoying a book of profound historical imagination, once the dilemma of their time stirred them to do so." (38)

During the last few years of his life Trevelyan's scholarly reputation went into a prolonged decline among professional academics. However, he was liked by Conservative politicians and Winston Churchill described Trevelyan as "one of our foremost national figures". (39) The Times commented that like his great-uncle, Thomas Babington Macaulay he was "the accredited interpreter to his age of the English past". (40)

George Macaulay Trevelyan died at his home in Cambridge on 20th July 1962.

Primary Sources

(1) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to Charles Trevelyan (13th August, 1914)

It grieves me deeply, and indeed makes me actually quite ill, not to be able to help and sympathise in anything that you are doing at this juncture. But frankly I am not going in for any pacific or anti war movements till the war is over to such a degree that I think peace ought to be made. I am very sorry if there has been any misunderstanding about it or if I seem to be failing you and the others we worked with in those nightmare days before war broke out. But when I parted with you at Euston I understood that beyond your resignation and letter (both splendid) you were going to do nothing except try and get administrative work... I certainly did not intend to do anything except try and find some useful function during the war for which I am still looking out.

(2) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to Charles Trevelyan (14th August, 1914)

I would rather not join your council. I will give you as much private advice as I am capable of but I am not a politician or a public man and I will not be drawn into it in any responsible manner. Consult me ad lib, needless to say... It has done you great credit and you will occupy a high moral position both with those who agree with you and those who disagree with you, provided you don't butt your head against a stone wall by continuing to argue about the past while we are all watching the North Sea mist and the French frontier. I cannot speak more strongly.

(3) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to Charles Trevelyan (15th August, 1914)

I have written you three letters of argument and now I have done with it. The difference between your policy and my advice may really be very little. And of course in so far as we differ I may be wrong. I never felt more uncertain of things in my life. But my personal instinct says to you `wait'... At any rate do not fear any real division of sympathy - even political - between us. I am simply doing and saying nothing until I know where we all are. And believe me my affection for you, deep as it was before, has been greatly deepened by the events of the last fortnight. And even politically it is you rather than the official Liberal party I shall be in with in the future - if I am in with anyone. I feel older, and if we survive the war, I shall probably set to writing history and not dabble in politics. But believe me I am far nearer to you in spirit and love than before.

(4) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to Charles Trevelyan (15th August, 1914)

I am sorry I wrote you such hysterical letters. Please tear them up. The fact is, as I have often told you, I am most unsuited for politics or action because I come to my conclusions (if I ever come to them!) by first feeling one thing strongly, then another and then settling to my final opinion. At present I feel nearer to a final opinion - of not having one at all except for general disgust and misery. I stand, or wobble, halfway between you and those ex-peace Liberals now trying to feel hearty about the war.

Whatever else I said in my letters I never suggested anything half as ridiculous as that you should go and fight! All I said, or meant, was that if I could find nothing else to do I might join the home front or the territorials. I am a fish out of water, for in fact I have nothing in the world that I am any good at except writing history, and until civilisation is partially resumed it is an art useless to anybody.

I have no doubt you will play a very fine and useful part, and of course you must play it in your own way. You are the only person in whose public doings I feel personal interest now. All the rest is much fear and a little hope for the community as a whole.

(5) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to Charles Trevelyan (15th March, 1914)

I am afraid we are a bad family at discussing things on which we disagree. When you put your views to me I can never debate them for fear of quarrelling, from a knowledge of my own temper. And then I feel I may have let you think I agree more than I do, and write letters in which perhaps I overstate our differences, or at least show temper - which is possibly less harmful on paper than in the flesh. Things will be alright between us on public matters after the war, provided we avoid heated discussions now, for there is no question of anything except difference of opinion. And on all private matters, and on matters connected with the war provided we keep off argument, we can meanwhile talk as freely as ever. Propose yourself to breakfast some day next week if you will. This I feel: that we both want the same sort of world. It is only a question of the means how to get back to (or on to) that sort of world out of the present smash, on which we differ. I daresay it takes all sorts to fight a war - and make a peace.

(6) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to Charles Trevelyan (May, 1917)

We are in the third day and night of the biggest battle we have had yet, and likely to be the most prolonged. It is a great pleasure to be in the fullness of activity and adventure day after day and night after night. Both in Gorizia and also in the high hills such scenes of beauty and romance as this big war in the mountains are wonderful indeed. It is a great life for me, rushing about from front to front and now and then to the base along this thirty miles of mountain battle. No one can have a pleasanter part in it.

(7) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to George Otto Trevelyan, quoted by Mary Moorman, George Macaulay Trevelyan (1980)

In this age of democracy and patriotism, I feel strongly drawn to write the history of England as I feel it, for the people... The war has cleared my mind of some party prejudices or points of view and I feel as if I have a conception of the development of English history, liberal but purely English and embracing the other elements. It might be a success as a literary work (otherwise I would not touch it). The doubt in my mind is whether it could have elbow room to be a literary success without being so long as to prevent the wide popularity which would alone justify the choice of it.

(8) David Cannadine, BBC World Service (22nd February, 2002)

Trevelyan had a very strong sense of national identity and he wrote his books in part because he had that sense of identity but he also wrote his books to promote that sense of national identity... He believed history had a social and political purpose and on the whole it was to reinforce a sense of identity and belonging rather than to subvert it.

(9) George Macaulay Trevelyan, letter to Robert Trevelyan (4th October, 1939)

The last thing Edward Grey (the Foreign Secretary at the outbreak of the First World War) said to me in the few weeks between the Nazi revolution and his death was, 'I see no hope for the world'. There is less now. One half of me suffers horribly, the other half is detached, because the 'world' that is threatened is not my world, which died years ago. I am a mere survivor. Life has been a great gift for which I am grateful, though I would gladly give it back now.

(10) John H. Plumb, G. M. Trevelyan (1951)

The war, which we were bringing to a successful end, had jeopardized the traditional pattern of English life, and in some ways destroyed it forever. This created among all classes a deep nostalgia for the way of life which we were losing. Then, again, the war had made conscious to millions that our national attitude to life was historically based, the result of centuries of slow growth, and that it was for the old, tried ways of life for which we were fighting. Winston Churchill, in his great war speeches made us all conscious of our past, as never before. And in this war, too, there were far more highly educated men and women in all ranks of all the services. The twenties and thirties of this century had witnessed a great extension of secondary school education, producing a vast public capable of reading and enjoying a book of profound historical imagination, once the dilemma of their time stirred them to do so.

(11) David Cannadine, George Macaulay Trevelyan : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Trevelyan's most sustained piece of writing during these years was English Social History (1944), which was intended to complement his earlier (and mainly political) History of England. It surveyed the broad sweep of national social life from the age of Chaucer to the close of the nineteenth century, and although wartime restrictions on paper supply initially held up its production, it soon proved to be the most successful of all his books, confirming his unrivalled position as the nation's historian laureate. Once again, the timing was just right. During the closing months of the Second World War, and in the longer years of Attlee's austerity, Trevelyan presented his readers with a beguiling picture of the past life of the nation, by turns inspiring and nostalgic. Written in the darkest years he had known, he poured out his patriotic feelings for what seemed to him the mortally endangered fabric of English life: landscape and locality, flora and fauna, places and people. Out of his wartime sense of despair and foreboding, he created his final historical masterpiece of public enlightenment, the (substantial) royalties from which he donated to the golden jubilee appeal of the National Trust.

(12) John H. Plumb, G. M. Trevelyan (1951)

Having read (Trevelyan's work), who could doubt that here was a great artist at work; at work in a medium, the writing of history, in which scholars have been plentiful and artists rare. But why did Trevelyan choose to use his gift of imagination in history rather than poetry?... One overwhelming reason cried aloud... that is his preoccupation with Time."

(13) Stefan Collini, English Pasts: Essays in History and Culture (1999)

Trevelyan was able to write with an easy familiarity about the families who had for so long ruled England, and yet in some ways his inherited sense of his destiny was a handicap: there were certain kinds of questions it didn't dispose him to ask... he was not prompted to be critically reflective about the assumptions and concepts he brought to the writing of history. In an important sense, Trevelyan was not an intellectual.

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)