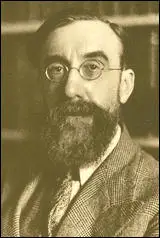

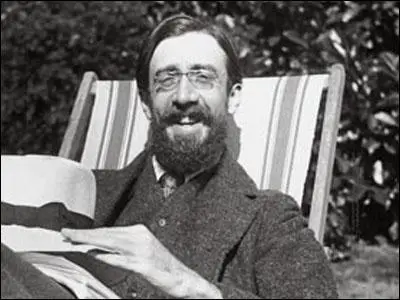

Lytton Strachey

Lytton Strachey, the eighth of the ten surviving children of Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Strachey (1817–1908) and his wife, Jane Grant Strachey (1840–1928), was born at Stowey House, Clapham Common, on 1st March 1880. Amongst his brother and sisters were James Strachey, Oliver Strachey and Philippa Strachey.

He was educated at Abbotsholme (1893–4); Leamington College (1894–7), Liverpool University (1897–9) and Trinity College (1899–1905), where he met his life-long friends, Leonard Woolf and Clive Bell. Other friends at university included George Mallory, John Maynard Keynes, and Bertrand Russell.

While at the University of Cambridge he was elected to the famous undergraduate society known as the Apostles. Other members included E. M. Forster, Roger Fry, George Edward Moore, Robert Trevelyan, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson and Desmond MacCarthy. According to his biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum: "With Keynes and J. T. Sheppard, Strachey turned the Apostles into more of a homosexual brotherhood than it had been. The publication of Moore's Principia ethica in 1903 marked for Strachey the beginning of a new age of reason. The book's analytic method and realistic epistemology, its fundamental distinction between instrumental and intrinsic good, its concept of organic unity, and its ideals of love and beauty all influenced Strachey's writings, beginning with the humorous Apostle papers that he wrote during his ten years as an active member."

In 1905 Lytton Strachey joined with several friends to discuss literary and artistic issues. The friends, who eventually became known as the Bloomsbury Group, included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Vita Sackville-West, Ottoline Morrell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Later that year Strachey met the artist Henry Lamb. He told his friend, Leonard Woolf: "He's run away from Manchester, became an artist, and grown side-whiskers... I didn't speak to him, but wanted to, because he really looked amazing, though of course very bad." Strachey made several unsuccessful attempts to seduce Lamb. His biographer, Michael Holroyd, has argued that Strachey was "convinced that Henry, with his angelic smile, his feminine skin and moments of incredible charm, could be converted to bisexuality".

According to Vanessa Curtis: "Lamb was an Adonis, with curly blond hair, a slim figure and a unique way of dressing in old-fashioned silk or velvet garments. He sported a gold earring and had a playful sense of humour. When he was in a good mood he proved an enchanting and alluring companion for Ottoline, but when he was depressed and bad-tempered, it took all of her natural patience and love to see them both through these difficult periods."

Strachey tried at first to earn a livelihood as a literary journalist. Between 1907 and 1909 he wrote nearly a hundred weekly reviews for The Spectator. He also contributed to Desmond MacCarthy's New Quarterly. Strachey left the magazine in 1909 in order to concentrate on his own writing. However, he continued to provide material for The Edinburgh Review.

Strachey remained in love with Henry Lamb, claimed that he was "a genius there can be no doubt, but whether a good or an evil one?" He added: "He is the most delightful companion in the world and the most unpleasant." Duncan Grant, another homosexual, got to know Lamb and told Strachey, "I'm convinced now he's a bad lot." Ottoline Morrell, who was having an affair with Lamb, also complained about his aggressive moods of depression: "The more I suffered from it the more he delighted in tormenting me."

Virginia Woolf fell in love with Strachey. However, he was having a sexual relationship with his cousin Duncan Grant. This ended painfully when Grant fell in love with John Maynard Keynes. On 25th January 1912 Lytton Strachey wrote to Ottoline Morrell: "He (Henry Lamb) has been charming, and I am much happier. I'm afraid I may have exaggerated his asperities; his affection I often feel to be miraculous. It was my sense of the value of our relationship, and my fear that it might come to an end, that made me cry out so loudly the very minute I was hurt."

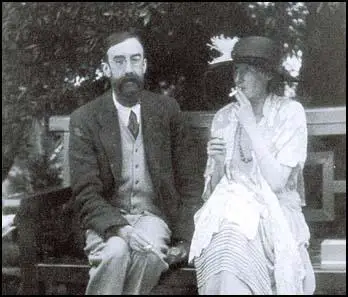

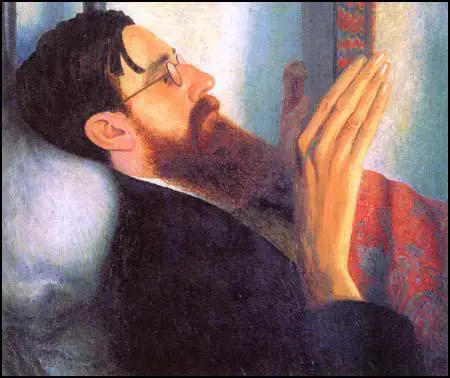

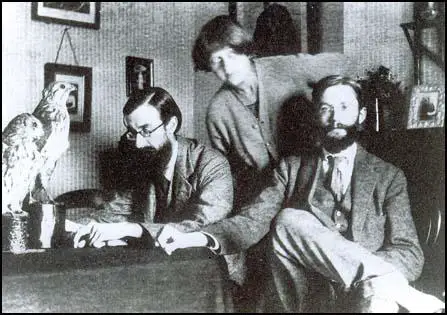

Lytton Strachey met Dora Carrington while staying with Virginia Woolf at Asheham House at Beddingham, near Lewes, she jointly leased with Leonard Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell and Duncan Grant. The author of Virginia Woolf's Women (2002) has pointed out: "Attracted to Carrington from the moment he first laid eyes on her, he had boldly tried to kiss her during a walk across the South Downs, the feeling of his beard prompting an enraged outburst of disgust from the unwilling recipient. According to legend, Carrington plotted frenzied revenge, creeping into Lytton's bedroom during the night with the intention of cutting off the detested beard. Instead, she was mesmerized by his eyes, which opened suddenly and regarded her intently. From that moment on, the two became virtually inseparable. Initially, Strachey's friends viewed the idea of Carrington and Lytton as a couple with repulsion; it was considered extremely inappropriate. Even though it was evident almost from the start that they were to enjoy a platonic relationship rather than a sexual one, the relationship was the talk of Bloomsbury for several months. They were a curious looking couple: Lytton was tall and lanky, bespectacled and with a curiously high-pitched voice, Carrington was short, chubby, eccentrically dressed and with daringly short hair."

Lytton Strachey refused to join the armed forces during the First World War. On 17th March 1916 he had appeared before the Hampstead Tribunal, accompanied by numerous friends and supporters to plead his case. This included the Liberal MP, Philip Morrell. When asked if he had a conscientious objection to all wars, he replied, "Oh no, not at all. Only this one." He was turned down for conscientious objector status but after his medical it was decided he was not fit enough for military service.

According to David Garnett: "They (Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey) became lovers, but physical love was made difficult and became impossible. The trouble on Lytton's side was his diffidence and feeling of inadequacy, and his being perpetually attracted by young men; and on Carrington's side her intense dislike of being a woman, which gave her a feeling of inferiority so that a normal and joyful relationship was next to impossible....When sexual love became difficult each of them tried to compensate for what the other could not give in a series of love affairs."

In 1917, Strachey set up home with Dora Carrington at Mill House, Tidmarsh, in Berkshire. Carrington's close friend, Dorothy Brett, was shocked by the decision: "How and why Carrington became so devoted to him I don't know. Why she submerged her talent and whole life in him, a mystery... Gertler's hopeless love for her, most of her friendships I think were partially discarded when she devoted herself to Lytton... I know that Lytton at first was not too kind with Carrington's lack of literary knowledge. She pandered to his sex obscenities, I saw her, so I got an idea of it. I ought not to be prejudiced. I think Gertler and I could not help being prejudiced. It was so difficult to understand how she could be attracted." Mark Gertler was furious and asked Carrington how she could "love a man like Strachey twice your age (36) and emaciated and old."

Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey did attempt a sexual relationship. She was willing to adapt to Strachey's homosexuality. However, she admitted in a letter to Strachey: "Hours were spent in front of the glass last night strapping the locks back, and trying to persuade myself that two cheeks like turnips on the top of a hoe bore some resemblance to a very well nourished youth of sixteen." Virginia Woolf assumed that Carrington was having a sexual relationship with Strachey. However, she recalled in her diary on 2nd July, 1918: "After tea Lytton and Carrington left the room ostensibly to copulate; but suspicion was aroused by a measured sound proceeding from the room, and on listening at the keyhole it was discovered that they were reading aloud Macaulay's Essays!"

In the summer of 1918, Dora's brother, Noel Carrington, introduced her to a friend, Ralph Partridge, who he had rowed with at University of Oxford, while they were on holiday in Scotland. On 4th July she wrote to Lytton Strachey that "Partridge shared all the best views of democracy and social reform... I hope I shall see him again - not very attractive to look at. Immensely big. But full of wit, and recklessness." Strachey replied: "The existence of Partridge is exciting. Will he come down here when you return? I hope so; but you give no suggestion of his appearance - except that he's immensely big - which may mean anything. And then, I have a slight fear that he may be simply a flirt."

Gretchen Gerzina, the author of A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989), pointed out "Partridge was the opposite of the kind of man who normally attracted her. He was tall and broad-shouldered and, in spite of her critical assessment of his looks, very handsome. He was in many ways a man's man, who wore his uniform as if he was meant to and was an athlete. Her friends in Bloomsbury took to calling him the major, and wondered how to assimilate such a seemingly stereotypical and masculine member of the English upper middle classes into their circle. They were to find that he fitted in rather well."

Ralph Partridge went to live with Carrington and Strachey at Mill House. Carrington began an affair with Partridge. According to Strachey's biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum, they created: "A polygonal ménage that survived the various affairs of both without destroying the deep love that lasted the rest of their lives. Strachey's relation to Carrington was partly paternal; he gave her a literary education while she painted and managed the household. Ralph Partridge... became indispensable to both Strachey, who fell in love with him, and Carrington." However, Frances Marshall denied that the two men were lovers and that Lytton quickly realised that Ralph was "completely heterosexual".

Gerald Brenan, had served with Ralph Partridge during the First World War, was a regular visitor to Mill House when he was in England. Brenan later described an early meeting with Carrington and Strachey: "Carrington came to the door and with one of her sweet, honeyed smiles welcomed me in. She was wearing a long cotton dress with a gathered skirt and her straight yellow hair, now beginning to turn brown, hung in a mop round her head. But the most striking thing about her was her eyes, which were of an intense shade of blue and very long-sighted, so that they took in everything they looked at in an instant. Passing a door through which I saw bicycles, we came into a sitting room, very simply furnished, in which a tall, thin, bearded man was stretched out in a wicker armchair with his long legs twisted together. Carrington introduced me to Lytton who, mumbling something I did not catch, held out a limp hand, and then led me through a glass door into an apple orchard where I saw Ralph, dressed in nothing but a pair of dirty white shorts, carrying a bucket."

In 1918 Lytton Strachey published Eminent Victorians (1918). The book was an irreverent look at the lives of Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold, Charles George Gordon and Henry Edward Manning. The historian, Gretchen Gerzina, has pointed out: "Not only did the book completely revise the art of biography from something long and dull to a quick-paced and creative form, but Lytton suddenly found himself a well-known and socially desirable character. Further he began to enjoy, for the first time in his life, a comfortable and independent income."

Strachey's biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum argues: "Strachey's preface to Eminent Victorians (1918) is a manifesto of modern biography, with its insistence that truth could now be only fragmentary, and that human beings were more than symptoms of history. The biographer's responsibility was to preserve both a becoming brevity and his own freedom of spirit, which for Strachey meant illustrating and exposing lives rather than imposing explanations on them.... Strachey's portraits are unified by a point of view that ironically juxtaposes the psychology and careers of his subjects."

Frances Marshall was a close friend of Dora Carrington during this period: "Her love for Lytton was the focus of her adult life, but she was by no means indifferent to the charms of young men, or of young women either for that matter; she was full of life and loved fun, but nothing must interfere with her all-important relation to Lytton. So, though she responded to Ralph's adoration, she at first did her best to divert him from his desire to marry her. When in the end she agreed, it was partly because he was so unhappy, and partly because she saw that the great friendship between Ralph and Lytton might actually consolidate her own position."

Virginia Woolf assumed that Carrington was having a sexual relationship with Lytton Strachey. However, she recalled in her diary on 2nd July, 1918: "After tea Lytton and Carrington left the room ostensibly to copulate; but suspicion was aroused by a measured sound proceeding from the room, and on listening at the keyhole it was discovered that they were reading aloud Macaulay's Essays!"

Dora Carrington married Ralph Partridge in 1921. She wrote to Lytton Strachey on her honeymoon: "So now I shall never tell you I do care again. It goes after today somewhere deep down inside me, and I'll not resurrect it to hurt either you or Ralph. Never again. He knows I'm not in love with him... I cried last night to think of a savage cynical fate which had made it impossible for my love ever to be used by you. You never knew, or never will know the very big and devastating love I had for you ... I shall be with you in two weeks, how lovely that will be. And this summer we shall all be very happy together."

In 1924 Strachey purchased Ham Spray House in Ham, Wiltshire, for £2,100. Dora and Ralph were invited to live with Strachey. According to Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994): "Ham Spray House had no drains or electric light and was in need of general repairs... The builders started work there in early spring... Even with some help from a legacy which Ralph had received on his father's death, it was all turning out to be fearfully expensive." Later, the loft at the east end of the house was converted into a studio for Carrington.

Julia Strachey, who visited her at Ham Spray House, recalls: "From a distance she (Carrington) looked a young creature, innocent and a little awkward, dressed in very odd frocks such as one would see in some quaint picture-book; but if one came closer and talked to her, one soon saw age scored around her eyes - and something, surely, a bit worse than that - a sort of illness, bodily or mental. She had darkly bruised, hallowed, almost battered sockets."

Brenan was a regular visitor to Ham Spray House when he was in England. Brenan later described an early meeting with Dora Carrington: "Carrington came to the door and with one of her sweet, honeyed smiles welcomed me in. She was wearing a long cotton dress with a gathered skirt and her straight yellow hair, now beginning to turn brown, hung in a mop round her head. But the most striking thing about her was her eyes, which were of an intense shade of blue and very long-sighted, so that they took in everything they looked at in an instant." Passing a door through which I saw bicycles, we came into a sitting room, very simply furnished, in which a tall, thin, bearded man was stretched out in a wicker armchair with his long legs twisted together. Carrington introduced me to Lytton who, mumbling something I did not catch, held out a limp hand, and then led me through a glass door into an apple orchard where I saw Ralph, dressed in nothing but a pair of dirty white shorts, carrying a bucket. He came forward to meet me with his big blue eyes rolling with fun and gaiety and carried me off to see the ducks and grey-streaked Chinese geese that he had recently bought... After this I was introduced to the tortoiseshell cat, which to his delight was rolling on its back in the grass in the frenzies of heat, and taken on to the kitchen where a buxom, fair-haired village girl of twenty, whom he addressed in a very flirtatious manner, was busy among the pots and pans.

Lytton Strachey had a sexual relationship with Philip Ritchie but he died of pneumonia in 1927. This was followed with a relationship with the publisher Roger Senhouse. Meanwhile Dora Carrington continued her affair with Gerald Brenan. Carrington enjoyed a close relationship with Alix Strachey, who she had attempted to seduce. She wrote in December 1928: "I send you my love. I wish it was for some use." She also had similar feelings for Julia Strachey. She told Brenan that she was strongly attracted to Julia and that she was "sleeping night after night in my house, and there's nothing to be done, but to admire her from a distance, and steal distracted kisses under cover of saying goodnight."

Dora Carrington wrote in her diary in 1929 that her sexual relationships were having a detrimental impact on her art. "I would like this year (since for the first time I seem to be without any relations to complicate me) to do more painting. But this is a resolution I have made for the last 10 years." However, later that year she began a relationship with Beakus Penrose, the younger brother of Roland Penrose. Her biographer, Gretchen Gerzina, has argued: "She may have found a sexual awakening with Henrietta - and there is no evidence that she ever had another woman as a lover - but ultimately it was a romance with a man she craved."

In 1931 Strachey became extremely ill. He had a fever that would not go away and constantly felt tired. At first he was diagnosed as having typhoid. He then saw another specialist who suggested it was ulcerative colitis. Frances Marshall pointed out: "In those days bulletins were published in the daily papers mentioning the progress of well-known people's illnesses. Lytton rated this degree of importance and the press often rang up, though the nice lady at the local exchange dealt with their queries and kept them supplied with news... On Christmas Day 1931 he was given up for dead. In the evening he made an astonishing recovery from near-unconsciousness."

Strachey told his nurse: "Darling Carrington. I love her. I always wanted to marry Carrington and I never did." Dora Carrington later recalled: "He could never have said anything more consoling. Not that I would have, even if he had asked me. But it was happiness to know he secretly had loved me so much." On 19th January 1932, Carrington asked his nurse if there was any chance that he might survive the illness. She replied: "Oh no - I don't think so now". Soon afterwards she went into the garage and tried to kill herself. However, during the night Ralph Partridge went looking for her and "found her in the garage with the car engine running, rushed in and dragged her out".

Lytton Strachey died of undiagnosed stomach cancer on 21st January 1932. Carrington went into deep depression. Gerald Brenan wrote to Carrington claiming: "To be happy you won't have to forget him, only to think of him without pain and that I really believe may be easier than you can now imagine."

Carrington kept a journal where she tried to communicate with Strachey. On 12th February 1932 Carrington wrote: "They say one should keep your standards & your values of life alive. But how can I when I only kept them for you. Everything was for you. I loved life just because you made it so perfect & now there is no one left to make jokes with or talk to... I see my paints, & think it is no use for Lytton will never see my pictures now, & I cry. And our happiness was getting so much more. This year there would have been no troubles, no disturbing loves... Everything was designed for this year. Last year we recovered from our emotions, & this autumn we were closer than we had ever been before. Oh darling Lytton you are dead & I can tell you nothing."

Frances Marshall was with Ralph Partridge when he received a phone-call on 11th March 1932. "The telephone rang, waking us. It was Tom Francis, the gardener who came daily from Ham; he was suffering terribly from shock, but had the presence of mind to tell us exactly what had happened: Carrington had shot herself but was still alive. Ralph rang up the Hungerford doctor asking him to go out to Ham Spray immediately; then, stopping only to collect a trained nurse, and taking Bunny with us for support, we drove at breakneck speed down the Great West Road.... We found her propped on rugs on her bedroom floor; the doctor had not dared to move her, but she had touched him greatly by asking him to fortify himself with a glass of sherry. Very characteristically, she first told Ralph she longed to die, and then (seeing his agony of mind) that she would do her best to get well. She died that same afternoon."

Primary Sources

(1) Virginia Woolf, diary (12th December, 1917)

Intimacy seems to me possible with him (Lytton Strachey) as with scarcely anyone; for besides tastes in common, I like and think I understand his feelings - even in their more capricious developments; for example in the matter of Carrington. He spoke of her, by the way, with a candour not flattering, though not at all malicious.

(2) Frances Partridge, Memories (1981)

As is now very well known, Lytton was a homosexual, in spite of which he was the great love of Carrington's life and had developed a close and happy friendship with her. Into this household Ralph was introduced, as a good-looking, healthy and lively-witted ex-Major of twenty-five. It did not take long for Lytton to fall in love with Ralph and Ralph with Carrington. Lytton soon realised that Ralph was hopelessly heterosexual, but they became lifelong friends - each, I would say, was "the best friend" of the other.

As for Carrington, the view of her as a wildly promiscuous femme fatale is, I am sure, quite incorrect. Her love for Lytton was the focus of her adult life, but she was by no means indifferent to the charms of young men, or of young women either for that matter; she was full of life and loved fun, but nothing must interfere with her all-important relation to Lytton. So, though she responded to Ralph's adoration, she at first did her best to divert him from his desire to marry her. When in the end she agreed, it was partly because he was so unhappy, and partly because she saw that the great friendship between Ralph and Lytton might actually consolidate her own position.

(3) Jane Hill, The Art of Dora Carrington (1994)

They (Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey) physical relations, even gave them a try... Sex was not going to work between them, and in a letter to Lytton in 1917 Carrington jokingly described how: "Hours were spent in front of the glass last night strapping the locks back, and trying to persuade myself that two cheeks like turnips on the top of a hoe bore some resemblance to a very well nourished youth of sixteen."

Carrington was petite, several heads shorter than Lytton and had a quirky way of dressing. Lytton was bohemian looking and emaciated. Both together and apart they were stared at in the street. Carrington's hair attracted hostile yells and Lytton's unfashionable beard provoked "goat" bleatings.

They were undoubtedly a curious looking couple but the point was, and is, there are "a great deal of a great many kinds of love" and Carrington and Lytton found a kind that suited them. They were both image breakers and advancing spirits who, each in their way, helped fashion the age in which they lived.

Quite bluntly, their friends were appalled. They thought the match ill-conceived and Virginia would later joke to her sister Vanessa of an evening at Tidmarsh Mill when Carrington and Lytton quietly withdrew, "ostensibly to copulate" but were found to be reading aloud from Macaulay. And if Lytton did Carrington a disservice at all, it was not by not loving her sufficiently but by failing to have the courage at that time to acknowledge to his oldest friends how important she was to him.

These friends, most of whom had known each other from university days at Cambridge, became known as the Bloomsbury Group, or Bloomsberries, as Molly MacCarthy nicknamed them. They continued to meet in Thoby Stephen's house in Gordon Square and came to include Thoby's sisters, Vanessa and Virginia.

Many years later, in her diary, Carrington puzzled over the "quintessence" of Bloomsbury and concluded: `It was a marvellous combination of the Highest intelligence, & appreciation of Literature combined with a lean humour & tremendous affection. They gave it back wards and forwards to each other like shuttlecocks only the shuttlecocks multiplied as they flew in the air." But on the whole they were Lytton's friends and Carrington's role in Bloomsbury was a satellite one. Carrington's friends did not form cliques in the way that Bloomsbury did and her cronies came from the Slade; they chose to live around the Hampshire-Wiltshire borders and had their studios in Chelsea, whereas the Bloomsbury Group lived in Sussex and Bloomsbury.

(4) David Garnett, Carrington (1970)

Lytton was homosexual, but he did not dislike women: quite the contrary. Some of his happiest relationships were with such women friends as Virginia Woolf, Dorelia John, Ottoline Morrell, his cousin Mary St John Hutchinson, and his sisters Dorothy Bussy and Pippa Strachey. By far the most important was his relationship with Carrington, with whom he fell in love in the spring and summer of 1916.

They became lovers, but physical love was made difficult and became impossible. The trouble on Lytton's side was his diffidence and feeling of inadequacy, and his being perpetually attracted by young men; and on Carrington's side her intense dislike of being a woman, which gave her a feeling of inferiority so that a normal and joyful relationship was next to impossible....

When sexual love became difficult each of them tried to compensate for what the other could not give in a series of love affairs. The first of Carrington's compensatory affairs was with Ralph Partridge, who forced her to marry him. It was not a success, but the link could not be broken...

I, a casual intimate, would say that she had the strength of character that one finds in a child but that a girl often loses when she becomes a woman. When she talked to me she seemed to be confiding a secret, and I was flattered. She made me feel like a child and she was a child herself.

She had indeed many of the childish, or adolescent characteristics that afflict girls at puberty. She never overcame her shame at being a woman, and her letters are full of references to menstruation. Although her sexual desire had greatly increased between her affair with Mark Gertler and that with Gerald Brenan, and although she was in love with Brenan as she had never been with Gertler, they follow a curiously similar pattern: almost the same deceptions, excuses and self-accusations are repeated in each relationship. And in each it was the hatred of being a woman which poisoned it.

Like a child, she found it hateful to choose; and after breaking off a relationship for ever she would immediately set about starting it again.

Like a child, she would tell lies which were bound to be found out and her life was complicated by continual deceptions and imbroglios.

She is an almost textbook case of the girl who can only be happy with a "father figure". She loved her father, hated her mother and found her only lasting happy relationship with Lytton Strachey exaggerating their age difference. When caught out, or in an emotional crisis, she often behaved like a child, confessing her guilt, telling more lies and appealing to Lytton for help and forgiveness.

(5) Dorothy Brett, letter to Michael Holroyd, quoted in Lytton Strachey: A Biography (1971)

How and why Carrington became so devoted to him I don't know. Why she submerged her talent and whole life in him, a mystery... Gertler's hopeless love for her, most of her friendships I think were partially discarded when she devoted herself to Lytton... I know that Lytton at first was not too kind with Carrington's lack of literary knowledge. She pandered to his sex obscenities, I saw her, so I got an idea of it. I ought not to be prejudiced. I think Gertler and I could not help being prejudiced. It was so difficult to understand how she could be attracted.

(6) David Garnett, The Flowers of the Forest (1955)

Lytton then said that he thought he was in love with Carrington. This was told me in a hesitating mixture of eagerness and deprecation. He had burst out because he needed to make a confidence. And then came the fear that he had been indiscreet. I was asked to swear not to repeat what he had told me to either Duncan or Vanessa. Duncan would tell Vanessa, and she would relate it in a letter to Virginia, and the fat would be in the fire. Ottoline would hear of it, which would be fatal. I did not breathe a word of Lytton's secret.

(7) Dora Carrington, letter to Roger Senhouse (December, 1931)

Lytton loved your flowers. He asked to hold them in his hands and for a long time buried his face in them, and said, how lovely. He sends you his fondest Love ... the Doctor said Lytton's state was much the same this morning. He couldn't say there was any improvement. The Diet is to be altered today. Perhaps it will have a good effect on the digestion. Leonard and Virginia dropped in today. It was nice to see them. Your freesias look so beautiful against the dull green-yellow wall in a pewter mug.

(8) Dora Carrington, undated letter to Lytton Strachey.

Lytton every time you come back I love you more. Something new which escaped me before in you completely surprises me. Do you know, when I think of missing a day with you it gives me proper pain inside. I can't help saying this at a risk of boring you.

(9) David Garnett, The Flowers of the Forest (1955)

He (Lytton Strachey) was alarmed lest his liaison with an apparently unsophisticated young woman should excite the malicious hilarity of Lady Ottoline Morrell - hilarity spiced perhaps with jealousy? He had to keep up his reputation of being indifferent to, and rather horrified by, attractive young women. There were solid reasons also. Carrington's parents had to be kept in ignorance, and Gertler's jealousy not excited... It was also convenient for Lytton to know that he was always a welcome guest at Lady Ottoline's country house ... it would be impossible to stay at Garsington if he were to be constantly teased about having fallen victim to the charms of a countrified girl.

(10) Vanessa Curtis, Virginia Woolf's Women (2002)

In her diary entry for Friday, 1 January 1932, Virginia rightly predicted that Carrington would try to commit suicide. Nobody was prepared, however, for Carrington's first attempt at suicide to take place before Lytton's actual death. She was saved - Lytton was suffering a bad attack at the time, which roused the household early and caused Ralph to realize her absence. He found her in the car, in their garage, with the engine running, and dragged her free. Carrington remained in bed until lunchtime on 21 January, when she crept back into Lytton's room and found that her soul mate with the beady eyes and high-pitched laugh was dying. She heard a bird singing outside the window and then Lytton drew his final breath. There was no funeral, and nobody recalls what became of Lytton's ashes, which were given to his brother James.

(11) Frances Partridge, Memories (1981)

In those days bulletins were published in the daily papers mentioning the progress of well-known people's illnesses. Lytton rated this degree of importance and the press often rang up, though the nice lady at the local exchange dealt with their queries and kept them supplied with news. I look back on this time of violent emotion, and am not sure with how much detachment I am even yet able to see it, but the fact remains that Lytton's danger did excite extremely strong feeling. Since then I have met with death in many forms, near and remote, and it seems to me there was a vein of hysteria in the agitation that surrounded Lytton's death-bed in Carrington's case it was because she knew she couldn't live without him; in Ralph's it was because the screw of anxiety was turned by her suspected intention to kill herself, while all Stracheys, in spite of their powerful intellects, were given to surprisingly uncontrolled outbursts.... Ralph was possessed by restlessness which he could only vent by driving in and out of Hungerford for medicines or other supplies.I remember one of the nurses, a small pale being, saying to me suddenly: "You know, whatever the specialists say, I think he's very bad indeed. His temperature dropped terribly low in the small hours last night. That's a dangerous sign. And there was a moment when Lytton, who had surprised everyone by his

stoicism as a patient, who had even made fun of his own sufferings, suddenly told Pippa he had had enough - he didn't want to go on living. This naturally upset her dreadfully; it was soon known throughout the house, and morale dropped instantly.

On Christmas Day 1931 he was given up for dead. In the evening he made an astonishing recovery from near-unconsciousness. Twice more he was given up by the doctors, and the third time he died.

(12) Dora Carrington, wrote a journal that expressed her thoughts on the death of Lytton Strachey (12th February 1932)

They say one should keep your standards & your values of life alive. But how can I when I only kept them for you. Everything was for you. I loved life just because you made it so perfect & now there is no one left to make jokes with or talk to... I see my paints, & think it is no use for Lytton will never see my pictures now, & I cry. And our happiness was getting so much more. This year there would have been no troubles, no disturbing loves... Everything was designed for this year. Last year we recovered from our emotions, & this autumn we were closer than we had ever been before. Oh darling Lytton you are dead & I can tell you nothing.