Ottoline Morrell

Ottoline Bentinck, the only daughter of Lieutenant-General Arthur Cavendish-Bentinck (1819–1877), was born at East Court, Hampshire on 16th June, 1873. Her mother, Augusta Mary Elizabeth Browne (1834–1893), was the younger daughter of Catherine de Montmorency and Henry Montague Browne, dean of Lismore.

Ottoline was educated at her home at Welbeck Abbey. Her biographer, Miranda Seymour, has argued: "Her romantic love of history was stimulated by helping her mother to unpack the Welbeck treasures; these included a magnificent set of Gobelin tapestries and paintings which were stacked, without frames, three deep around the walls of the empty staterooms when they arrived."

In 1879 Ottoline's half-brother William Cavendish-Bentinck inherited the title and estates of their wealthy relative, William Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, the 5th Duke of Portland. The following year her mother was granted the title, Baroness Bolsover. According to Vanessa Curtis: "They moved into a charming house, St Anne's Hill in Chertsey, but the relationship between mother and daughter began to go sour. Lady Bolsover became an obsessive invalid, terrified of being left alone, and her daughter, now aged sixteen, was expected to spend every night sleeping in the same room."

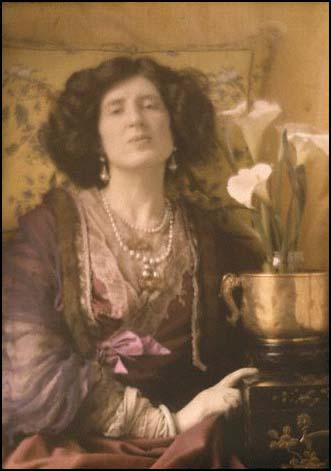

After the death of her mother in 1893 she spent time in Italy. She met Axel Munthe, a rich doctor in his forties, and spent time at his home in Capri. It was a brief but intense affair and was eventually brought to to an end because of religious differences. On her return to London she became friendly with the married Herbert Asquith. Ottoline's unusual looks were extremely attractive to men. Hermione Lee has argued that: "Ottoline's appearance was legendarily idiosyncratic. She spoke in a weird, nasal, cooing, sing-song drawl. Her amazing looks were at once sexy and grotesque: she was very tall, with a huge head of copper-coloured hair, turquoise eyes and great beaky features. She wore fantastical highly-coloured clothes and hats with great style and bravado."

In 1899, Ottoline began studying political economy and Roman history as an out-student at Somerville College. One day, while "cycling to college dressed all in white with her red hair blazing" she caught the eye of Philip Morrell. At first she rejected his advances. As one biographer pointed out: "Ottoline was still determined to find her father figure, and this solicitor, however charming and friendly, seemed too young." Morrell pursued Ottoline for two years. In letter to him she revealed grave doubts about the physical side of their relationship. However, she was willing to have a relationship with him "based on affection and trust rather than passion." They were eventually married in February 1902.

According to Vanessa Curtis: "Unexpectedly, the roles were reversed immediately after their honeymoon; Philip suddenly admitted that he found it hard to be sexually attracted to her. This was a shock to Ottoline, but it did not affect the immense loyalty that they both had to the marriage, which stood the test of time and was strong enough to survive their considerably involved love affairs with other people."

The couple settled at 39 Grosvenor Road. Morrell was an active member of the Liberal Party and in 1903 she helped him in his unsuccessful attempt to represent Henley in Oxfordshire. Morrell was a great womaniser and his first illegitimate child, a daughter, was born in 1904. Around this time they agreed to have an open marriage. Ottoline had twins on 18th May 1906. The boy, named Hugh, died of a brain haemorrhage, two days later. Her daughter survived and was named Julian in memory of her mother's old friend in Cornwall. Soon afterwards she was told that the traumatic birth had ended any chance of her having further children. The child was buried at Clifton Hampden and Ottoline continued to visit the graveyard for the next thirty years.

In the 1906 General Election Morrell won Henley. The family now set up home at 44 Bedford Square in Bloomsbury. In 1907 the Morrells rented a second home, Peppard Cottage. Ottoline became very interested in modern art and became influenced by the views of Roger Fry. He suggested that she took a look at the work of Mark Gertler and Stanley Spencer. Ottoline also received advice from the art collector, Edward Marsh and the writer, Gilbert Cannan.

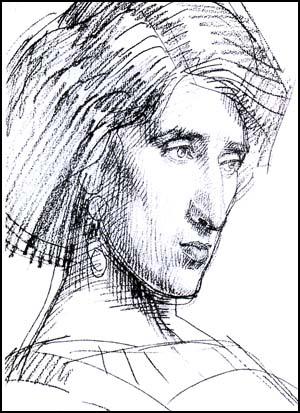

David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) described Ottoline Morrell as "almost six feet tall, with striking red-gold hair, turquoise eyes, and an odd, horse-like face, colourful clothes copied from medieval and Renaissance patterns." Ottoline took a very keen interest in Gertler's work and visited him in his East End studio. She later recalled walking along "the mean, hot, stuffy, smelly, little street" where Gertler worked. Lady Ottoline was dazzled by the "intense, tangible, ruthless, hot quality" of his paintings.

After her visit to Gertler's studio she told Roger Fry: "I feel strongly now that every penny one can save ought to be given to young artists. At least, we who really feel the beauty and wonder of art ought to help them, young creators have such a terrible struggle." Ottoline purchased Gertler's The Fruit Sorters, on behalf of the Contemporary Art Society. She showed it to Walter Sickert, and described Gertler "standing by his picture, thin, erect and trembling internally, if not externally, at the excitement of having his work looked at and discussed by anyone like Sickert, whom he so respected."

Lady Ottoline invited Mark Gertler to tea at her home in London. She asked him "if he didn't find it hard reconciling his home life with the life he lived at the Slade, and with Mr Eddie Marsh". He admitted "that he could not but feel antagonistic to the smart and the worldly, while at the same time he felt depressed by the want of cultivation of his own people." He also told Lady Ottoline that "nothing for a long time has given me so much happiness" as her visit and "I thank you for it."

In a letter to Dora Carrington, Gertler described Ottoline as a "passionate and ambitious and exceedingly observant and sensitive". She took him to concerts, theatre trips and expensive restaurants. Edward Marsh also took him to the opera. Gertler told Carrington that "everybody is being very nice to me just now... this makes me very happy."

Ottoline Morrell also visited the home of Stanley Spencer in Cookham. She described Spencer as looking like a "healthy, red-faced farm labourer". She commented that Spencer was an "intense genius" and purchased one of his drawings. She also promoted the careers of Augustus John, Duncan Grant, Jacob Epstein and Henry Lamb. Her biographer, Miranda Seymour has argued: "Some became her lovers; few were able to resist her combination of innocence, aristocracy, and the singularity of a true eccentric." In 1907, she began holding weekly parties at Bedford Square for the artists and writers she met and whom she hoped to help by offering introductions to rich patrons.

In 1909 Dorelia McNeill, the partner of Augustus John, introduced Henry Lamb to Ottoline Morrell in 1909. The following year they began an intense affair. Ottoline wrote in May 1910: "It was perhaps a half maternal instinct that pushed me towards this twisted and interesting figure. Yet he was wonderfully attractive, sometimes like a vision of Blake, sometimes a version of Stendhal's Julien Sorel. I was in love with him... but all his heart is given to Dorelia (McNeill)."

Roger Fry, who accepted a large sum of money from Ottoline towards help for his mentally ill wife, began to fall in love with her. However, his advances were rejected because of her involvement with Lamb. According to Vanessa Curtis: "Lamb was an Adonis, with curly blond hair, a slim figure and a unique way of dressing in old-fashioned silk or velvet garments. He sported a gold earring and had a playful sense of humour. When he was in a good mood he proved an enchanting and alluring companion for Ottoline, but when he was depressed and bad-tempered, it took all of her natural patience and love to see them both through these difficult periods."

In December 1908, Ottoline had tea with Vanessa Stephen and Virginia Stephen at their home in Fitzroy Square, Bloomsbury. Virginia was especially impressed with Ottoline and confessed to Violet Dickinson that their relationship was like "sitting under a huge lily, absorbing pollen like a seduced bee." Vanessa believed that Ottoline was bisexual and that she was physically attracted to her sister. In her memoirs, Ottoline admitted that she was entranced by Virginia: "This strange, lovely, furtive creature never seemed to me to be made of common flesh and blood. She comes and goes, she folds her cloak around her and vanishes, having shot into her victim's heart a quiverful of teasing arrows."

Ottoline Morrell continued to be involved with Henry Lamb. She had competition from Lytton Strachey. He was a homosexual and made several unsuccessful attempts to seduce Lamb. His biographer, Michael Holroyd, has argued that Strachey was "convinced that Henry, with his angelic smile, his feminine skin and moments of incredible charm, could be converted to bisexuality". Strachey claimed that Lamb was "a genius there can be no doubt, but whether a good or an evil one?" He added: "He is the most delightful companion in the world and the most unpleasant." Duncan Grant, another homosexual, got to know Lamb and told Strachey, "I'm convinced now he's a bad lot." Ottoline Morrell also complained about his aggressive moods of depression: "The more I suffered from it the more he delighted in tormenting me."

In December 1908, Ottoline had tea with Vanessa Stephen and Virginia Stephen at their home in Fitzroy Square, Bloomsbury. Virginia was especially impressed with Ottoline and confessed to Violet Dickinson that their relationship was like "sitting under a huge lily, absorbing pollen like a seduced bee." Vanessa believed that Ottoline was bisexual and that she was physically attracted to her sister. In her memoirs, Ottoline admitted that she was entranced by Virginia: "This strange, lovely, furtive creature never seemed to me to be made of common flesh and blood. She comes and goes, she folds her cloak around her and vanishes, having shot into her victim's heart a quiverful of teasing arrows."

Ottoline Morrell continued to be involved with Henry Lamb. She had competition from Lytton Strachey. He was a homosexual and made several unsuccessful attempts to seduce Lamb. His biographer, Michael Holroyd, has argued that Strachey was "convinced that Henry, with his angelic smile, his feminine skin and moments of incredible charm, could be converted to bisexuality". Strachey claimed that Lamb was "a genius there can be no doubt, but whether a good or an evil one?" He added: "He is the most delightful companion in the world and the most unpleasant." Duncan Grant, another homosexual, got to know Lamb and told Strachey, "I'm convinced now he's a bad lot." Ottoline Morrell also complained about his aggressive moods of depression: "The more I suffered from it the more he delighted in tormenting me."

Ottoline began an affair with Bertrand Russell in March 1911. Her biographer, Miranda Seymour has pointed out: "In 1911, disenchanted by his first wife, Alys Pearsall Smith, Russell turned to Ottoline and was, for a time, inspired by her, although he could not sympathize with her Christian beliefs. Their relationship was fought over and celebrated in a remarkable correspondence, often amounting to four letters a day. Ottoline's sexual coldness and Russell's possessiveness caused difficulties which prompted suicide threats on both sides." Ottoline later recalled that the love of his mind ("the beauty and transcendence of his thoughts") led her to overlook the fact that she could "hardly bear the lack of physical attraction".

Vanessa Curtis argues: "Their affair, which lasted for the next five years, was bet with problems and imbalances from the start... It was always Ottoline who threatened to end the relationship, and so they would get stuck in patterns of enforced silences and absences, which would be broken by a miserable Bertrand begging to see her, professing undying love... Bertie eventually left Alys, his wife, after a bitter and nasty feud, but Ottoline would not even contemplate leaving Philip. Her marriage meant too much to her, and Philip had started suffering from periods of mental instability, which meant that he had a greater need for his wife's love and support."

Roger Fry was very jealous of her relationship with Bertrand Russell and he reacted by "angrily and unfairly accused her of spreading rumours abroad concerning his love for her." The rift with Fry was not healed for another sixteen years. Ottoline also had domestic problems during this period. Philip Morrell began to suffer from episodes of mental strain that his doctor defined as a "nervous illness", a term used at the time to describe any sort of mental illness.

Ottoline's relationship with her daughter was always difficult. Miranda Seymour has argued: "Ottoline's flaws remain more immediately apparent than her virtues. She was a demanding and oppressive mother, she could be tyrannical in her desire to control the lives of her friends, and she was reckless in her gossip about other people's private opinions. Her craving for affection could seem discomforting."

In 1914 Mark Gertler arranged for Ottoline to meet his girlfriend, Dora Carrington. Ottoline also met D.H. Lawrence, who had just published a book of short stories. Lawrence introduced her to his new wife, Frieda Lawrence and two other friends, Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murray. Lawrence later commented on Ottoline's desire for sexual relationships with men: "She had no natural sufficiency, there was a terrible void, a lack, a deficiency of being within her. And she wanted someone to close up this deficiency."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Ottoline and Philip Morrell joined forces with several other leading political figures to establish the Union of Democratic Control. The UDC had three main objectives: (1) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be parliamentary control over foreign policy; (2) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic European countries in an attempt to form an organisation to help prevent future conflicts; (3) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might provide a cause for future wars.

Other members of the UDC included Charles Trevelyan, Norman Angell, E. D. Morel, Ramsay MacDonald, John Morley, J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Mary Sheepshanks, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville and Olive Schreiner.

The Union of Democratic Control soon emerged at the most important of all the anti-war organizations in Britain and by 1915 had 300,000 members. The Daily Express listed details of future UDC meetings and encouraged its readers to go and break-up them up. Although the UDC complained to the Home Secretary about what it called "an incitement to violence" by the newspaper, he refused to take any action. Over the next few months the police refuse to protect UDC speakers and they were often attacked by angry crowds. After one particularly violent event on 29th November, 1915, the newspaper proudly reported the "utter rout of the pro-Germans".

The Morrells purchased Garsington Manor near Oxford at the beginning of the First World War and became a refuge for conscientious objectors. They worked on the property's farm as a way of escaping prosecution. It also became a meeting place for a group of intellectuals described as the Bloomsbury Group. Members included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, David Garnett, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Gerald Brenan, Ralph Partridge, Vita Sackville-West, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

David Garnett described Garsington Manor in his autobiography, The Flowers of the Forest (1955): "The oak panelling had been painted a dark peacock blue-green; the bare and sombre dignity of Elizabethan wood and stone had been overwhelmed with an almost oriental magnificence: the luxuries of silk curtains and Persian carpets, cushions and pouffes. Ottoline's pack of pug dogs trotted everywhere and added to the Beardsley quality, which was one half of her natural taste. The characteristic of every house in which Ottoline lived was its smell and the smell of Garsington was stronger than that of Bedford Square. It reeked of the bowls of potpourri and orris-root which stood on every mantelpiece, side table and window-sill and of the desiccated oranges, studded with cloves, which Ottoline loved making. The walls were covered with a variety of pictures. Italian pictures and bric-a-brac, drawings by John, watercolours for fans by Conder, who was rumoured to have been one of Ottoline's first conquests, paintings by Duncan and Gertler and a dozen other of the younger artists."

One of the members of this group, Frances Partridge, later recalled in her autobiography, Memories (1981): "They were not a group, but a number of very different individuals, who shared certain attitudes to life, and happened to be friends or lovers. To say they were unconventional suggests deliberate flouting of rules; it was rather that they were quite uninterested in conventions, but passionately in ideas. Generally speaking they were left-wing, atheists, pacifists in the First World War, lovers of the arts and travel, avid readers, Francophiles. Apart from the various occupations such as writing, painting, economics, which they pursued with dedication, what they enjoyed most was talk - talk of every description, from the most abstract to the most hilariously ribald and profane."

In 1916 Ottoline Morrell invited Dorothy Brett to her home, Garsington Manor near Oxford. Morrell described Brett as "a slim, pretty young woman, looking much younger than she really was. She had a Joe Chamberlain nose, a peach-like complexion, rather a rabbit mouth and no chin". Ottoline provided her with a studio at Garsington, that she later shared with Mark Gertler.

Another permanent guest at this time was the writer, Lytton Strachey. He complained to Barbara Hiles on 17th July 1916: "I came here with the notion of working. There are now no intervals between the weekends - the flux and the reflux is endless - and I sit quivering among a surging mesh of pugs, peacocks, pianolas, and humans - if humans they can be called - the inhabitants of Circe's cave. I am now faced not only with Carrington and Brett (more or less permanencies now) but Gertler, who is at the present moment carolling a rag-time in union with her Ladyship."

Other people who spent time at Garsington Manor included Siegfried Sassoon, Aldous Huxley, D.H. Lawrence, Frieda Lawrence, Ethel Smyth, Katherine Mansfield, John Middleton Murray, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Herbert Asquith, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot. Ottoline's affair with Bertram Russell came to an end during the First World War. She then began a relationship with with Lionel Gomme, a young bisexual stonemason who died of a brain haemorrhage in 1922.

Ottoline Morrell remained in close contact with Virginia Woolf, but it was always a difficult relationship. In her memoirs, Ottoline recalled: "She seemed to feel certain of her own eminence. It is true, but it is rather crushing, for I feel she is very contemptuous of other people. When I stretched out a hand to feel another woman, I found only a very lovely, clear intellect." Ottoline was fully aware of Virginia's abilities, she had "such energy and vitality and seemed to me far the most imaginative and mastery intellect that I had met for many years."

Morrell also became very close to D.H. Lawrence who she helped with his writing by supporting him emotionally and financially. In December 1916 he showed her his unpublished novel, Women in Love. On reading it she was extremely upset at the unflattering portrayal of herself that was thinly disguised in the character of Hermione Roddice. Philip Morrell went to Lawrence's agent and threatened to bring legal action against any publisher who brought out the book.

Aldous Huxley also betrayed Ottoline's friendship by putting her in his novel Crome Yellow. The character, Priscilla Wimbush, was described as having a "large square middle-aged face, with a massive projecting nose and little greenish eyes, the whole surmounted by a lofty and elaborate coiffure of a curiously improbable shade of orange." Ottoline was also furious about his rude and unfunny descriptions of her friends, Dorothy Brett, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell and Mark Gertler. She told Huxley that his book reminded her of "poor photography".

Despite these rejections Ottoline Morrell continued to help young artists and writers. The novelist Henry Green commented that "to literally hundreds of young men like myself who were not worth her little finger, but she took trouble over them and they went out into the world very different from what they would have been if they had not known her." T.S. Eliot, who received a lot of help from Ottoline early in his career admitted that "it is very difficult to think of anyone who meant so much to me". Augustus John agreed and called her a "most noble and generous soul… there is no one to be compared to her. "

Financial difficulties led to the sale of Garsington Manor in 1928. Ottoline and Philip Morrell moved to a more modest home, 10 Gower Street. Soon afterwards she developed cancer of the jaw, which meant a long stay in hospital and an operation to have her lower teeth extracted and part of her jawbone removed. She told her friends that the "pain was indescribable". As Vanessa Curtis pointed out: "But far worse than the pain was the indignity to live with a seriously disfigured chin, which she did her best to disguise by swathing veils and scarves beneath it, tying them with typical Ottoline flamboyance."

Ottoline Morrell suffered a stroke in 1937. She received treatment at Sherwood Park, a clinic in Tunbridge Wells run by Dr A. J. Cameron. He treated her with Prontosil, an untested new drug. She got worse and Cameron committed suicide on 19th April, 1938. Two days later Lady Ottoline Morrell died. She left a message to her friends "not to send any wreaths for my dead body, but gladden my soul for the poor and destitute - those who have no shelter".

Primary Sources

(1) Virginia Woolf, Old Bloomsbury (c. 1940)

When indeed one remembers that drawing room full of people, the pale yellows and pinks of the brocades, the Italian chairs, the Persian rugs, the embroideries, the tassels, the scent, the pomegranates, the pugs, the pot-pourri and Ottoline bearing down upon one from afar in her white shawl with the great scarlet flowers on it and sweeping one away out of the large room and the crowd into a little room with her alone, where she plied one with questions that were so intimate and so intense... I think my excitement may be excused.

(2) Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf (1996)

In 1909, Ottoline seemed to her a "fancy-dress" character, an alluring, ridiculous phenomenon. Lady Ottoline, then thirty-six, was unhappily married to Philip Morrell, a Liberal MP. She had a three-year-old daughter, Julian (the survivor of twins), and since 1907 she had been turning herself into a famous hostess for writers and artists at 44 Bedford Square and at Peppard Cottage, near Henley. In 1908 she was having an affair with Augustus John; by 1910 she was in love with Henry Lamb, for whom Lytton Strachey also developed a passion. The following year she had a brief, unsatisfactory liaison with Roger Fry, and her dramatic love-affair with Bertrand Russell began. During these years - while suffering from numerous illnesses - she was helping Philip Morrell fight his seat in the elections of January and November 1910, and enthusiastically helping young artists through the Modern Art Association and the Post-Impressionist exhibition.

Ottoline's appearance was legendarily idiosyncratic. She spoke in a weird, nasal, cooing, sing-song drawl. Her amazing looks were at once sexy and grotesque: she was very tall, with a huge head of copper-coloured hair, turquoise eyes and great beaky features. She wore fantastical highly-coloured clothes and hats with great style and bravado, and had pronounced tastes in interior decoration. The general effect was one of dazzling "lustre and illusion".

(3) Dora Carrington, letter to Lytton Strachey (28th July 1916)

I spent a wretched time here since I wrote this letter to you. I was dismal enough about Mark and then suddenly without any warning Philip Morrell after dinner asked me to walk round the pond with him and started without any preface, to say, how disappointed he had been to hear I was a virgin! How wrong I was in my attitude to Mark and then proceeded to give me a lecture for a quarter of an hour! Winding up by a gloomy story of his brother who committed suicide. Ottoline then seized me on my return to the house and talked for one hour and a half in the asparagus bed, on the subject, far into the dark night. Only she was human and did see something of what I meant. And also suddenly forgot herself, and told me truthfully about herself and Bertie [the mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell]. But this attack on the virgins is like the worst Verdun on-slaughter and really I do not see why it matters so much to them all. Mark suddenly announced that he is leaving today (yesterday), and complicated feelings immediately come up inside me.

(4) Frances Partridge, diary entry (11th June, 1930)

Afterwards to a private view at Coolings, to be opened by Ottoline dressed as usual most eccentrically in tawdry satin finery. When tea was served she dropped a bun and chased it avidly with claw-like hands all over the floor. Arthur Waley was there, his face bright orange from ski-ing in Norway, the Henry Lambs, the Keyneses and Faith, who was full of the news that Wollaston, a Fellow of King's, had just been shot dead by an undergraduate. She hurried to tell this stop-press news to Maynard, who had been a great friend of his and was so upset that he left immediately.

(5) (5)Gretchen Gerzina, A Life of Dora Carrington: 1893-1932 (1989)

Through Gilbert Cannan and Eddie Marsh, Gertler was broadening his social horizons. Both moved in very different circles from his and while he did not always appreciate their friends, his growing reputation as an artist and entertaining guest made Gertler something of a social find. His and Carrington's introduction to the Bloomsbury group involved Marsh. In May 1914, Lady Ottoline Morrell, who with her husband Philip Morrell was becoming an important pacifist and patron of the arts at this time, wrote to invite Gertler and Carrington to a production of The Magic Flute. Gertler found that he had to break an appointment with Marsh in order to accept, "But I feel it is so difficult to refuse Lady Ottoline - then there is Carrington too." Having made the invitation, Lady Ottoline changed her plans, putting it off for a few days and "was not yet certain whether she can have us to dinner or not on that date". Behind the scenes Carrington and Gertler were reshuffling all of their plans in order to accommodate hers.

Lady Ottoline, a friend of Gilbert Cannan and half-sister to the Duke of Portland, had introduced herself to Gertler by visiting his studio home in Whitechapel. There she had been saddened by the low ceilings and his obvious poverty, but highly impressed by his work. She soon became his patron and champion, welcoming him (and later Carrington) to her houses in Bedford Square and at Garsington near Oxford. She remained his friend and ally, taking his side whenever Carrington frustrated him, but caring about both of them. They in turn defended her; she was easily caricatured because of her long nose, prominent chin and reddish hair, her sometimes heavy make-up, and flamboyant clothes, and many writers (including D. H. Lawrence in Women in Love) portrayed her cruelly in their works. Even her other friends and recipients of her generosity in Bloomsbury frequently made fun of her, which upset Carrington greatly.

(6) (6)David Garnett, The Flowers of the Forest (1955)

The oak panelling had been painted a dark peacock blue-green; the bare and sombre dignity of Elizabethan wood and stone had been overwhelmed with an almost oriental magnificence: the luxuries of silk curtains and Persian carpets, cushions and pouffes. Ottoline's pack of pug dogs trotted everywhere and added to the Beardsley quality, which was one half of her natural taste. The characteristic of every house in which Ottoline lived was its smell and the smell of Garsington was stronger than that of Bedford Square. It reeked of the bowls of potpourri and orris-root which stood on every mantelpiece, side table and window-sill and of the desiccated oranges, studded with cloves, which Ottoline loved making. The walls were covered with a variety of pictures. Italian pictures and bric-a-brac, drawings by John, watercolours for fans by Conder, who was rumoured to have been one of Ottoline's first conquests, paintings by Duncan and Gertler and a dozen other of the younger artists.