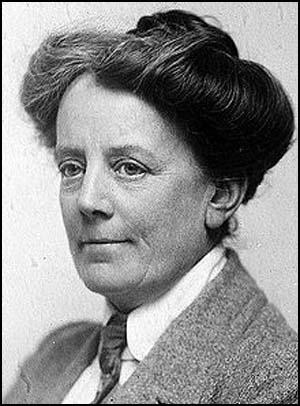

Ethel Smyth

Ethel Smyth, the fourth of the eight children of Major-General John Hall Smyth (1815–1894) and his wife, Emma Struth Smythe (1824–1891), was born at 5 Lower Seymour Street, London, on 22nd April 1858. In her autobiography she claimed that her father was very strict: "I think on the whole we were a naughty and very quarrelsome crew... Of course we merited and came in for a good deal of punishment, including having our ears boxed, which in those days was not considered dangerous... I think I am the only one of the six Miss Smyths who has ever been really thrashed; the crime was stealing some barley sugar, and though caught in the very act, persistently denying the theft. Thereupon my father beat me with one of grandmama's knitting needles, a thing about two and a half feet long with an ivory knob at one end.... Hit hard he did, for a fortnight later, when I joined Alice, who had been away all this time at an aunt's, she noticed strange marks on my person while bathing me, and was informed by me that it came from sitting on my crinoline... Even in after years my mother could not bear to think about that thrashing."

Ethel was much closer to her mother: "At this stage of my existence I stood in great awe of my father, but adored my mother, and remember her dazzling apparitions at our bedside when she would come to kiss us good-night before starting for an evening party. I often lay sleepless and weeping at the thought of her one day growing old and less beautiful. Besides this, wild passions for girls and women a great deal older than myself made up a large part of my emotional life, and it was my habit to increase the anguish of love by fancying its object was prey to some terrible disease that would shortly snatch her from me."

Emma Struth Smythe introduced her daughter to music: "She was in fact one of the most naturally musical people I have ever known; how deeply so I found out in after years when she came to Leipzig to see me, and I watched her listening for the first time to a Beethoven symphony - watched her face softening, tightening, relaxing again as each beauty I specially counted on went home. Old friends maintained that when she was young her singing would have melted a stone, which I can well believe all the warm, living qualities that made her so lovable must have got into it. When I knew her she had almost lost her voice, but enough remained to judge of its strangely moving timbre. Later on she loved to hear me sing, and it saddens me to think how seldom I gratified her when we were by ourselves; but I always was lazy about singing."

Her biographer, Elizabeth Kertesz, has pointed out: "She first became aware of her musical vocation in 1870, under the influence of a governess who had studied at the Leipzig conservatory. She was educated at home, with her five sisters, but was sent to school in Putney between 1872 and 1875. In spite of musical activities at school, she did not really begin to develop her talent until she returned to Frimley and received tuition from Alexander Ewing. This new friend and mentor encouraged her musical aspirations, while his wife, Juliana, foretold an author's career for their enthusiastic pupil. The fruitful contact was brought to an abrupt end by General Smyth's distrust of Ewing, but Smyth had already made up her mind to study composition in Leipzig."

However, Major-General John Hall Smyth refused permission for her to study music and insisted that she got married. According to Kertesz: "With her goal set, Smyth chafed at the social obligations of a marriageable young woman. She had tacit support from her mother, but quarrelled violently with her disapproving father and eventually resorted to militant tactics, locking herself in her room and refusing to attend social engagements. General Smyth finally agreed to her demand and she set off for Leipzig in July 1877. This was indeed a victory for a young woman of her class."

Smyth found Leipzig Conservatory disappointing and after a year she abandoned this institution to study privately with the composer Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843–1900). Herzogenberg's wife, Lisl, became Smyth's first great love and the two women grew very close. Another biographer, Ronald Crichton, has commented: "On the whole it seems that the greatest and most enduring of her 'passions' were for older women with whom, through character or circumstance or both, physical gratification was out of the question even to one of her on-coming disposition."

Ethel Smyth claimed in her autobiography, Impressions that Remained (1919): "The moment has come to express regret that unlike other women writers of memoirs, such as Sophie Kowalewski, George Sand and Marie Bashkirtseff - if for a moment I may class myself with such as these - I have so far no orthodox love-affairs to relate, neither soulful sentiment for musician of genius, nor perilous passion conceived among the reeds of the Crostewitz lake for proud Prussian guardsman. In my letters to Lisl, where all the secrets of my heart stand revealed, I again and again express a conviction it is foolish to insist upon, so obvious is it, that the most perfect relation of all must be the love between man and woman, but this seemed to me, given my life and outlook, probably an unachievable thing."

In 1878 she went to live with the Herzogenberg family. Heinrich von Herzogenberg introduced Ethel to Johannes Brahms. She later recalled: "To my mingled delight and horror I learned, too, that Henschel had actually spoken to him about my work, telling him I had never studied, that he really ought to look at it and so on; and after the general rehearsal this good friend clutched and presented me all unawares. At that time Brahms was clean shaven, and in the whirl of emotion I only remember a strong alarming face, very penetrating bright blue eyes, and my own desire to sink through the floor when he said, as I then thought by way of a compliment, but as I now know in a spirit of scathing irony, So this is the young lady who writes sonatas and doesn't know counterpoint!"

In 1882 Ethel Smyth met Lisl Herzogenberg's sister Julia and her husband, Henry B. Brewster (1850–1908) in Florence. Brewster was an American writer and philosopher who had grown up in Europe. In her autobiography Impressions that Remained (1919) she pointed out: "It may be remembered that the Brewsters held unusual views concerning the bond between man and wife, views which up to the time of my arrival on the scene had not been put to the proof by the touch of reality. My second visit to Florence was fated to supply the test. Harry Brewster and I, two natures to all appearance diametrically opposed, had gradually come to realize that our roots were in the same soil - and this I think is the real meaning of the phrase to complete one another - that there was between us one of those links that are part of the Eternity which lies behind and before Time. A chance wind having fanned and revealed at the last moment, as so often happens, what had long been smouldering in either heart, unsuspected by the other, the situation had been frankly faced and discussed by all three of us; and I then learned, to my astonishment, that his feeling for me was of long standing, and that the present eventuality had not only been foreseen by Julia from the first, but frequently discussed between them. To sum up the position as baldly as possible, Julia, who believed the whole thing to be imaginary on both sides, maintained it was incumbent on us to establish, in the course of further intercourse, whether realities or illusions were in question. After that - and surely there was no hurry - the next step could be decided on. This view H. B. allowed was reasonable. My position, however, was that there could be no next step, inasmuch as it was my obvious duty to break off intercourse with him at once and for ever. And when I left Italy that chapter was closed as far as I was concerned." Her biographer, Elizabeth Kertesz, has argued: "She returned to Italy the following winter and found herself reciprocating Brewster's growing affection for her, although she tried to act honourably by breaking off all contact with him. Despite this renunciation, Lisl's loyalties were torn, and in 1885 she severed all contact with Smyth."

Ethel Smyth began to make a name for herself as a composer during this period. She wrote piano music and works for a variety of chamber ensembles in a style strongly influenced by the Brahmsian tradition. Most of these works were performed privately, but her string quintet (op. 1, 1883) and her violin sonata (op. 7, 1887) were played publicly at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. She returned to England, where no one knew of her German success. Ethel also had a great voice. Maurice Baring described her singing as "the rare and exquisite quality and deelicacy of her voice, the strange thrill and wail, the distinction and distinct, clear utterance".

In 1889 Ethel Smyth launched herself on the English musical scene with performances at the Crystal Palace of her Serenade in D and her Overture to Antony and Cleopatra . This was followed by the première of her Mass in D, performed by the Royal Choral Society and premiered at the Royal Albert Hallby the Royal Choral Society in 1893. These works established Smyth as the most important woman composer of her time. Claire Tomalin has argued: "Ethel's work did not stand in the way of her social activities, or her many passionate friendships. Throughout her life, she loved intensely, without regard to age or gender... She did defy - or perhaps rather ignore - all the stereotypes of her time, whether in matters of work, sex, class or even manners.... Over the next two decades she studied, composed and met most of the great figures of the day."

After Julia Brewster died in 1895 Ethel and Brewster were able to pursue their relationship more openly. Maurice Baring was a close friend: "His (Harry Brewster) appearance was striking; he had a fair beard and the eyes of a seer... someone said he looked like a Rembrandt. His manner was suave, and at first one thought him inscrutable - a person whom one could never know, surrounded as it were by a hedge of roses. When I got to know him better I found the whole secret of Brewster was this: he was absolutely himself; he said quite simply and calmly what he thought, and the truth is sometimes disconcerting when calmly expressed." According to Elizabeth Kertesz: "They neither married nor had children, and retained separate homes - she in England, he in Italy - but Brewster was a stable presence in Smyth's often stormy life.... his importance to her unaltered by her concurrent relationships with women." Ethel claimed that "Harry was never jealous of my women friends, in fact he held, as I do, that every new affection that comes into your life enriches older ties".

Smyth also wrote operas such as Der Wald (1901). Her work was difficult and her friend, Mabel Dodge, hired the His Majesty's Theatre for six performances of The Wreckers, a work that she had written with Henry B. Brewster. Smythe managed to persuade Thomas Beecham to conduct the work. Smyth had difficulty working with Beecham: "As the rehearsals wore on I discovered that in more respects than one my new friend was a disconcerting person to work with. For one thing he was never less than half an hour late, a habit which in that department of music life bears cruelly on all concerned. I also noticed that not only was it an effort to him to allow for the limitations of the human voice, to give the singers time to enunciate and drive home their words, but that qua musical instrument he really disliked the genus singer, which seemed an unfortunate trait in an opera conductor. In short, my impression was that his real passion was concert rather than opera conducting."

In his autobiography, A Mingled Chime (1944), Beecham explained why the opera was rarely produced: "This fine piece (The Wreckers) has never had a convincing representation owing to the apparent impossibility of finding an Anglo-Saxon soprano who can interpret revealingly that splendid and original figure, the tragic heroine Thirza. Neither in this part nor that of Mark, the tenor, have I heard or seen more than a tithe of that intensity and spiritual exaltation without which these two characters must fail to make their mark."

Ethel Smyth was a passionate supporter of women's rights and was a close friend of the three sisters, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Agnes Garrett. All the women were members of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Ethel went to live with them at Firs Cottage, in the village of Rustington. As Ethel pointed out: "Agnes and Rhoda Garrett, who were among the first women in England to start business on their own account and by that time were well-known house decorators of the Morris school... Both women were a good deal older than I, how much I never knew - nor wished to know, for Rhoda and I agreed that age and income are relative things concerning which statistics are tiresome and misleading."

Ethel Smyth met Emmeline Pankhurst in the summer of 1910. Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause (2003), has argued: "Ethel Smyth, an endearingly eccentric bisexual composer who cheerfully confessed to having little or no political background and to caring even less about votes for women - until she met and fell passionately in love with the founder of the WSPU. At first glance Ethel Smyth made a curious companion for a political leader who, despite the violence which attached itself to her movement, remained resolutely feminine. While Emmeline usually had some lace about her person Ethel always dressed in tweeds, deerstalker and tie. Emmeline tended to attack every venture with passion while her new friend regarded the world with a wry, amused cynicism. Ethel, unlike Emmeline, had few sexual or personal inhibitions. But the two women, who at fifty-two were exactly the same age, immediately formed so close an attachment that Ethel decided to give two years of her life to the cause."

Smyth joined the Women's Social and Political Union and the following year she composed the WSPU battle song, The March of the Women. In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Smythe took part in these activities and was with Emmeline Pankhurst when they were arrested: "The Downing Street window selected by Mrs Pankhurst was duly bombarded - I think she had two shots at it before they arrested her - but the stones never got anywhere near the objective. I broke my window successfully and was bailed out of Vine Street at midnight by wonderful Mr Pethick-Lawrence, who was ever ready to take root in any police station, his money bag between his feet, at any hour of the day or night."

Ethel Smyth was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. In her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933) she wrote: "The ensuing two months in Holloway, though one never got accustomed to an unpleasant sensation when the iron door was slammed and the key turned, were as nothing to me because Mrs Pankhurst was in with us. The merciful matron put us in adjoining cells, and at exercise, in chapel and on such other occasions as a kind-hearted matron can make for a prisoner, we saw more of each other than the protocol permitted. For instance she would often leave us together in Mrs Pankhurst's cell at tea-time 'just for a moment', lock us in, and forget to come back and conduct me to my own. But, as with policemen and detectives, Mrs Pankhurst refused to be softened by these favours, or by obviously sincere protestations of the 'it-hurts-me-more-than-it-hurts-you' order. And when, with an accent of cold scorn, she said, 'I would throw up any job rather than treat women as you say it is your didy to treat us,' the worst of it was that everyone knew this was nothing but the truth. According to Fran Abrams: "Ethel helped to organise athletic sports in the prison yard, which was even decorated by the women in the suffragette colours. As the women marched around the exercise yard singing March of the Women, an anthem she had composed for them, Ethel looked on from the window of her cell, marking time with a toothbrush."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Ethel Smyth has pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

It has been argued by Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007), that Smythe was a lesbian and that she was probably the lover of Emmeline Pankhurst, Edith Craig and Christabel Marshall. She also became involved with Virginia Woolf, who wrote in her diary: "An old woman of seventy-one has fallen in love with me... It is like being caught by a giant crab."

In 1922 Smyth was reated a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. She also wrote two volumes of autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933) and What Happened Next (1940).

Ethel Smyth died on 8th May 1944.

Primary Sources

(1) Ronald Crichton, Ethel Smyth (1987)

Virginia Woolf was much younger, Emmeline Pankhurst and Edith Somerville were the same age as Ethel Smyth, but they were exceptions. On the whole it seems that the greatest and most enduring of her 'passions' were for older women with whom, through character or circumstance or both, physical gratification was out of the question even to one of her on-coming disposition. Though much was written to them in the form of letters, there is little of Edith Somerville and Virginia Woolf in the autobiographies for they came into her life too late.

(2) Maurice Baring, The Puppet Show of Memory (1922)

His (Harry Brewster) appearance was striking; he had a fair beard and the eyes of a seer... someone said he looked like a Rembrandt. His manner was suave, and at first one thought him inscrutable - a person whom one could never know, surrounded as it were by a hedge of roses. When I got to know him better I found the whole secret of Brewster was this: he was absolutely himself; he said quite simply and calmly what he thought, and the truth is sometimes disconcerting when calmly expressed.

(3) Ronald Crichton, Ethel Smyth (1987)

Brewster tamed Ethel without bruising her spirit and corrected what he saw as barbarous Germanic influence with a wider appreciation of French civilization. The ground was fertile but not, except by her mother in childhood, tilled, and Ethel's affection for Germany, even where music was concerned, was never blinkered. She befriended Brewster's two children (his wife was Julia von Stockhausen, sister of Lisl von Herzogenberg), Clotilde, who studied architecture in London and married a fellow student, Percy Feilding, and Christopher, who married a daughter of the sculptor Hildebrand.

Of the profoundest events in their friendship, the moment when Harry Brewster finally became her lover, and his death at the age of fifty-eight, she writes with a reticence in strange contrast with the outspokenness of pen and speech that caused justifiable alarm to family and friends. In spite of her frankness she was neither uncharitable nor prurient. She did not believe, for instance, what others assumed, that the painter Sargent and her sister Mary Hunter were lovers. This was not due to unworldliness or impercipience, for she had a keen eye, indeed a relish, for the quirks of human nature and for details of physical behaviour. With the forward sweep of her writing there goes a rarer gift, an ability to draw a character swiftly and sharply comparable to Sargent's skill with the charcoal stick, shown brilliantly in his sketch of her singing at the piano. Her subject may be an eccentric neighbour in the heath country round Aldershot which was her English home all her life, a Leipzig worthy or a half-forgotten figure from the world of music such as the Franco-Irish composer Augusta Holmes, often encountered in books about nineteenth-century Paris but surely never brought to life as here.

(4) Ronald Crichton, Ethel Smyth (1987)

Ethel Smyth wrote a respectable amount of music though her cruvre was not large for a composer who died in her eighties. Faure and Vaughan Williams, respectively a generation older and younger, both lived long and wrote much more. In later life, in her fifties, deafness began to slow her down and she did not have the kind of inner ear that could defeat it; unlike Faure, who went deaf at much the same age, she needed to hear what she wrote. Besides, there were always too many distractions: sport, travel (some, though not all, in pursuit of performances of her operas), friendships and the letter-writing that went with them. Lisl von Herzogenberg, Henry Brewster's sister-in-law and Ethel's mentor in Leipzig, was incapable of understanding this duality in her protegee's character, yet she was right to scent danger and warn her. Lisl could not have foreseen that the pull between circumstance (upper-class military life) and the chosen profession would become one of the things that made Ethel Smyth the extraordinary person she was.

(5) Thomas Beecham, A Mingled Chime (1944)

This fine piece (The Wreckers) has never had a convincing representation owing to the apparent impossibility of finding an Anglo-Saxon soprano who can interpret revealingly that splendid and original figure, the tragic heroine Thirza. Neither in this part nor that of Mark, the tenor, have I heard or seen more than a tithe of that intensity and spiritual exaltation without which these two characters must fail to make their mark.

(6) Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained (1919)

I think on the whole we were a naughty and very quarrelsome crew. My father once wrote and pinned on the wall: 'If you have nothing pleasant to say hold your tongue'; an adage which, though excellent as receipt for getting on in society, was unpopular in a nursery such as ours, for words lead to blows and we happened to love fighting. There was one terrific battle between Mary and myself in the course of which I threw a knife that wounded her chin, to which she responded with a fork that hung for a moment just below my eye, Johnny having in the meantime crawled under the table.

Of course we merited and came in for a good deal of punishment, including having our ears boxed, which in those days was not considered dangerous, and my mother's dramatic instinct came out strongly in her technique as ear-boxer. With lips tightly shut she would whip out her hand, hold it close to one's nose, palm upwards, for quite a long time, as much as to say, 'Look at this! You'll feel it presently' - and then ... smack!

I think I am the only one of the six Miss Smyths who has ever been really thrashed; the crime was stealing some barley sugar, and though caught in the very act, persistently denying the theft. Thereupon my father beat me with one of grandmama's knitting needles, a thing about two and a half feet long with an ivory knob at one end. He was the least cruel of men, and opponents of corporal punishment will say its brutalizing effect is proved by the fact that when I howled he merely said, 'The more noise you make the harder I'll hit you.' Hit hard he did, for a fortnight later, when I joined Alice, who had been away all this time at an aunt's, she noticed strange marks on my person while bathing me, and was informed by me that it came from sitting on my crinoline.

Even in after years my mother could not bear to think about that thrashing. All I can say is it left no wound in my memory as did snubs, and was the only punishment that ever had any effect - for I dreaded being hurt. Indeed to run the risk of ordinary pains and penalties, and make the best of it when overtaken by them, was quite part of our scheme, and I am glad to know that some of our happy thoughts when under punishment extorted unwilling admiration even from our chastisers.

(7) Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained (1919)

At this stage of my existence I stood in great awe of my father, but adored my mother, and remember her dazzling apparitions at our bedside when she would come to kiss us good-night before starting for an evening party. I often lay sleepless and weeping at the thought of her one day growing old and less beautiful. Besides this, wild passions for girls and women a great deal older than myself made up a large part of my emotional life, and it was my habit to increase the anguish of love by fancying its object was prey to some terrible disease that would shortly snatch her from me. Whether this was simply morbidity, or a precocious intuition of a truth insisted on by poets all down literature - from Jonathan and David to Tristan and Isolde - that Love and Death are twins, I do not know, but anyhow I was not to be put off by glaring evidence of robust health. I loved for instance Ellinor B., a stout young lady who rode to hounds, was a great toxophilite as they were called in those days, led the singing in church in a stentorian voice, and was altogether as bouncing a specimen of healthy young womanhood as could be met with. Persuaded nevertheless that this strong-growing flower was doomed to fade shortly, I one day asked Maunsell if he did not think she was dying of consumption, and shall never forget my distress when he answered with a loud guffaw, 'Consumption? Yes, I should think she may die of consumption, but not the kind you mean!'

(8) Ethel Smyth Impressions that Remained (1919)

She (her mother) had a great gift for languages, and besides French and Hindustani knew German, Italian and Spanish. Though she had visited none of the countries in which these languages are spoken except France and India, nor had any practice since her schoolroom days, when occasion demanded off she would start with fluency and idiomatic correctness, not to speak of an accent she owed to her musical ears.

For her strongest gift was undoubtedly music; she was in fact one of the most naturally musical people I have ever known; how deeply so I found out in after years when she came to Leipzig to see me, and I watched her listening for the first time to a Beethoven symphony - watched her face softening, tightening, relaxing again as each beauty I specially counted on went home. Old friends maintained that when she was young her singing would have melted a stone, which I can well believe all the warm, living qualities that made her so lovable must have got into it. When I knew her she had almost lost her voice, but enough remained to judge of its strangely moving timbre. Later on she loved to hear me sing, and it saddens me to think how seldom I gratified her when we were by ourselves; but I always was lazy about singing.

(9) Ethel Smyth Impressions that Remained (1919)

It was in the summer of 1875 - a summer that in any case was to rob her of her favourite daughter - that the great sorrow of my mother's life happened. Alice had been engaged for some time to a young Scotsman, Harry Davidson, and the couple were waiting for an impending improvement in his prospects, when Mary, who had been out but a short time, also became engaged - not to Maunsell B. but to Charlie Hunter, brother of a schoolfriend of hers. There was to be a joint wedding in July, and the invitations, of which I had mercifully kept a list, had been sent out, when it became evident that Johnny's slow martyrdom endured by him with marvellous fortitude and sweetness, was coming to an end. For a fortnight he had suffered from terrible headaches, as usual making no complaint, and one night at dessert, taking up a biscuit, he said, 'How queer, I can't read the letters on this biscuit.' He then sank back, as we thought fainting, but a tumour on the brain had burst, and he became unconscious by slow degrees, his last conscious words being, 'Don't let this illness of mine stop the girls' weddings.'

We used to take it in turn to watch nightly beside his bed, and when relieved spent the rest of the night on a sofa in the hall close by, so as to be ready if needed. One night, after my watch was over, I stumbled and fell, and there I was found when the housemaid came in the morning to open the shutters, asleep on the floor... as I had fallen. Such is the sleep hunger of youth. There had just been time to cancel the invitations, but as it seemed that he might linger for some time yet, the marriages took place one morning at Frimley Church, none of the family but myself being present. The bridegrooms went back to London from the church door, and a few days afterwards Johnny died. That afternoon the children had been sent to a kind neighbour, and Nelly says that on their return mother met them at the front door to tell them he was dead, tears streaming down her face yet trying to smile - a picture of grief that has remained with them ever since.

This was my first acquaintance with death, and the sight of that strange unfamiliar face impressed me terribly and painfully. The day after the funeral the married couples departed, and I became the eldest at home.

(10) Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained (1919)

Early in January 1878 came the event to which, ever since its advance announcement by Henschel in Friedrichsroda, everything else had seemed but a prelude, the arrival of Brahms in Leipzig to conduct his new Symphony in D major. Henschel turned up from Berlin at the same time, and from him I gathered that at the extra rehearsal, to which we outsiders were not admitted, there had been a good deal of friction. Brahms, as I found out later, for Henschel would have been far too loyal to admit it, was not only an indifferent conductor, but had the knack of rubbing orchestras up the wrong way.... As for Brahms,accustomed to the brilliant quality of Viennese orchestras, which was to entrance me equally when I came to know them, he found his own race, the North Germans, cold and sticky, and let them feel it....

To my mingled delight and horror I learned, too, that Henschel had actually spoken to him about my work, telling him I had never studied, that he really ought to look at it and so on; and after the general rehearsal this good friend clutched and presented me all unawares. At that time Brahms was clean shaven, and in the whirl of emotion I only remember a strong alarming face, very penetrating bright blue eyes, and my own desire to sink through the floor when he said, as I then thought by way of a compliment, but as I now know in a spirit of scathing irony, "So this is the young lady who writes sonatas and doesn't know counterpoint!"

(11) Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained (1919)

The moment has come to express regret that unlike other women writers of memoirs, such as Sophie Kowalewski, George Sand and Marie Bashkirtseff - if for a moment I may class myself with such as these - I have so far no orthodox love-affairs to relate, neither soulful sentiment for musician of genius, nor perilous passion conceived among the reeds of the Crostewitz lake for proud Prussian guardsman. In my letters to Lisl, where all the secrets of my heart stand revealed, I again and again express a conviction it is foolish to insist upon, so obvious is it, that the most perfect relation of all must be the love between man and woman, but this seemed to me, given my life and outlook, probably an unachievable thing. Where should be found the man whose existence could blend with mine without loss of duality on either side? My work must and would always be the first consideration, and the idea that men might think one wanted to catch them checked incipient romance. For a space I had imagined myself in love with the husband of one of my friends - a ridiculous fancy at once confessed to his wife, who was rather gratified and not at all alarmed. This fleeting sentiment was mastered and consigned to limbo without its object being any the wiser; and all the time I was more or less aware that had this individual been eligible such an idea would never have entered my head. As in the case of my own admirers, immunity from consequences favoured the tender illusion of a hopeless attachment. What Fate had in reserve for me as regards the supremest relation of all who could say? Meanwhile the desire to be looked after, helped and loved was as imperative as the instinct of independence that seemed predominant. And as, in order to receive you must give ... give I did!

(12) Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained (1919)

I have found in women's affection a peculiar understanding, mothering quality that is a thing apart. Perhaps too I had a foreknowledge of the difficulties that in a world arranged by man for man's convenience beset the woman who leaves the traditional path to compete for bread and butter, honours and emoluments - difficulties honest men are more aware of, perhaps, than she of the sheltered life. I had no theories about it then but I think I guessed it. Even among the conformists I saw good, brave women obliged because of their sex to give way before dullness, foolishness or brutality; and in natures inclined to side with the handicapped these things kindle sympathy and admiration. And further it is a fact that the people who have helped me most at difficult moments of my musical career, beginning with my own sister, Mary, have been members of my own sex. Thus it comes to pass that my relations with certain women, all exceptional personalities I think, are shining threads in my life....

Barbara Hamlet had often spoken to me of Agnes and Rhoda Garrett, who were among the first women in England to start business on their own account and by that time were well-known house decorators of the Morris school. Agnes was sister to Mrs Fawcett and Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson - Rhoda, their cousin, rather older than Agnes, daughter of a clergyman whose second wife had practically turned her predecessor's children out of the house to fend for themselves. Late in the autumn of 1880 Barbara introduced me to these great friends of hers, and during the next two years their house became the focus of my English life owing to the friendship that sprang up between Rhoda and me.

Both women were a good deal older than I, how much I never knew - nor wished to know, for Rhoda and I agreed that age and income are relative things concerning which statistics are tiresome and misleading. How shall one describe that magic personality of hers, at once elusive and clear cut, shy and audacious? - a dark cloud with a burning heart - something that smoulders in repose and bursts into flame at a touch. ...Though the most alive, amusing, and amused of people, to me at least the sombre background was always there - perhaps because the shell was so obviously too frail for the spirit. One knew of the terrible struggle in the past to support herself and the young brothers and sisters; that she had been dogged by ill-health as well as poverty - heroic, unflinching through all. Agnes once said to me, 'Rhoda has had more pain in her life than was good for her,' but no one guessed that like her brother Edmund - champion of Rhodes, youthful collaborator with Lord Milner, cut off at the zenith of his powers - she carried in her the seeds of tubercular disease. And yet when the end came there was little of surprise in one's grief; thus again and again had one seen falling stars burn out.

I spoke of her humour; on the whole I think she was more amusing than anyone I have ever met - a wit half scornful, always surprising, as unlike everyone else's as was her person ... a slim, lithe being, very dark, with deep-set burning eyes that I once made her laugh by saying reminded me of a cat in a coal scuttle. Yet cat's eves are never tender, and hers could be the tenderest in the world.

I always think the feel of a hand as it grasps yours is a determining factor in human relationships, and all her friends must well remember Rhoda's - the soft, soft skin that only dark people have, the firm, wiry, delicate fingers. My reason tells me she was almost plain, but one looked at no one else when she was in a room. There was an enigmatic quality in her witchery behind which the grand lines, the purity and nobility of her soul, stood out like the bone in some enchanted landscape. No one had a more subtle hold on the imagination of her friends, and when she died it was as if laughter, astonishment, warmth, light, mystery, had been cut off at the source. The beauty of the relation between the cousins, and of that home life in Gower Street, remains with us who knew them as certain musical phrases haunt the melomaniac, and but for Agnes, who stood as far as was possible between her and the slings and arrows which are the reward of pioneers, no doubt Rhoda's life would have spent itself earlier. Her every burden, human and otherwise, was shouldered by Agnes, and both had a way of discovering waifs and strays of art more or less worsted by life whose sanctuary their house henceforth became.

I think I have never been happier in my life than at the old thatched cottage they rented at Rustington. An exhausting fight against the stream of prejudice, such as the Garretts had waged for many years, was not to be my portion till later. Of course both cousins and all their friends were ardent Suffragists, and I wonder now at the patience with which they supported my total indifference on the subject - an indifference I was to make up for thirty years later.

Their great friends the Parrys had a house close by, and besides helping me with invaluable musical criticism and advice Hubert Parry lent me a canoe, in which on very calm days, cautiously dressed in bathing costume, I put out to sea. There too I got to know the Fawcetts, and saw how that living monument of courage, the blind Postmaster General, impressed the country people as he strode up and down the hills in the company of his wife. I thought Mrs Fawcett rather cold, but an incident that happened the summer after the death of Rhoda, to whom she was devoted, taught me otherwise. One day when I was singing an Irish melody I had often sung at Rustington - 'At the Mid Hour of Night' - I suddenly noticed that tears were rolling down her cheeks, and presently she got up and quietly left the room. After that for many years I never saw her. Then came the acute Suffrage struggle, during which the gulf that separated Militants from National Unionists belched forth flames, but through all those years, remembering that incident, I always thought of Mrs Fawcett with affection.

(13) Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained (1919)

It may be remembered that the Brewsters held unusual views concerning the bond between man and wife, views which up to the time of my arrival on the scene had not been put to the proof by the touch of reality. My second visit to Florence was fated to supply the test. Harry Brewster and I, two natures to all appearance diametrically opposed, had gradually come to realize that our roots were in the same soil - and this I think is the real meaning of the phrase to complete one another - that there was between us one of those links that are part of the Eternity which lies behind and before Time. A chance wind having fanned and revealed at the last moment, as so often happens, what had long been smouldering in either heart, unsuspected by the other, the situation had been frankly faced and discussed by all three of us; and I then learned, to my astonishment, that his feeling for me was of long standing, and that the present eventuality had not only been foreseen by Julia from the first, but frequently discussed between them. To sum up the position as baldly as possible, Julia, who believed the whole thing to be imaginary on both sides, maintained it was incumbent on us to establish, in the course of further intercourse, whether realities or illusions were in question. After that - and surely there was no hurry - the next step could be decided on. This view H. B. allowed was reasonable. My position, however, was that there could be no next step, inasmuch as it was my obvious duty to break off intercourse with him at once and for ever. And when I left Italy that chapter was closed as far as I was concerned.

(14) Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained (1919)

As the rehearsals wore on I discovered that in more respects than one my new friend was a disconcerting person to work with. For one thing he was never less than half an hour late, a habit which in that department of music life bears cruelly on all concerned. I also noticed that not only was it an effort to him to allow for the limitations of the human voice, to give the singers time to enunciate and drive home their words, but that qua musical instrument he really disliked the genus singer, which seemed an unfortunate trait in an opera conductor. In short, my impression was that his real passion was concert rather than opera conducting.

Today Beecham denies that this was ever the case, and maintains that he had been interested in opera since he was five! and his first step in active music life was to present himself at the office of an opera company with two operas of his own composition. But this seems to me quite compatible with an angle towards the human voice which, at the time I am speaking of, struck me as lacking sympathy.

(15) Ethel Smyth, Female Pipings for Eden (1933)

There was a great meeting at the Albert Hall, one of those astounding money-making efforts so often put through by the WSPU, and on this occasion Mrs Pankhurst and Annie Kenney - most irresistible of blue-eyed beggars - were the chief protagonists. Sometimes as much as £6,000 to £7,000 - on one occasion, late in the fight, £10,000 - would be raised in a couple of hours, but as 'money talks', these painful facts found no mention in the Press!

Militancy was a costly business and much depended on these Albert Hall meetings; hence it is not surprising that as the day approached the faces of the leaders grew grave. On the way to the hall Mrs Pankhurst's silence seemed to me to betoken a touch of nervousness, and as the Union car, flaunting its purple, white and green colours, passed slowly down Piccadilly, booing and jeering men and women lined the pavement, only held back from more active demonstrations by the presence of the police.

Suddenly the car pulled up with a jerk; a woman was down, caught by our mudguard; there was hatred and menace in the air and loud execrations. In a twinkling Mrs Pankhurst was on the pavement, her arm round the blowzy victim of Suffragette brutality, while with the innate authority that never failed her she ordered a policeman to fetch an ambulance. And so manifest was her distress, so obviously sincere her bitter regret that because of the meeting she could not herself take the injured one to the hospital, that in less time than it takes to tell the story it was the crowd that was comforting Mrs Pankhurst, assuring her (which was the case) that no harm had been done, that the lady was quite all right. And all this time Mrs Pankhurst's face, soft with pity, radiant with love, was the face of an angel, and her arm still encircled the lady, who was now quite recovered and inclined to be voluble. Finally the crowd of late enemies urged her to get back into the car, 'else you'll be late for the meeting!' Half-crowns passed, and we drove off, cheers speeding us on our way. But as she settled down somewhat violently in her seat, Mrs Pankhurst might have been heard ejaculating in a furious undertone, 'Drunken old beast, I wish we'd run over her!'

(16) Ethel Smyth, Female Pipings for Eden (1933)

Mr Asquith decided that a red herring was urgently called for. Adult Suffrage had always been, of course, a chief plank in the Labour platform, consequently the Government had proceeded in November 1911 to launch an Adult Suffrage Bill, for men only, with a 'possible' amendment in favour of women should it pass. The idea was to detach the Labour vote from the Conciliation Bill and ensure its defeat, and our false Labour friends in the House of Commons, quite aware that this Adult Suffrage Bill had not the ghost of a chance of becoming law, but too afraid of their constituencies not to vote for it, now began pointing out that some quite other Women's Bill, to be launched on some unspecified date, a Bill giving women the vote on equal terms with men, was surely worthier our noble aspirations than a limited 'aristocratic' measure like the Conciliation Bill?

Of course the trick was a complete success. The Adult Suffrage Bill was thrown out, Mr Lloyd George was soon boasting openly of having 'torpedoed' the Conciliation Bill, and Mrs Fawcett, the least excitable, most level-headed leader that ever steered a political party, wrote, "If it had been Mr Asquith's object to enrage every woman to the point of frenzy, he could not have acted with greater perspicacity."

It was, I think, in connection with this monstrous piece of trickery - for Mr Asquith had ceased not to promise that in this Parliament the women were going to have a square deal - that a great window-breaking raid was planned. It was to be timed so as to lodge some 150 of us in Holloway simultaneously, which we knew would put the Government to considerable expense and inconvenience; and one of the most enchanting, certainly the most comic of my magic-lantern slides, shows Mrs Pankhurst training herself to break a window. As dusk came on we repaired to a selected part of Hook Heath - a far from blasted heath; indeed, owing to the golf course, a somewhat over-sophisticated heath that lies in front of my house. And near the largest fir tree we could find I dumped down a collection of nice round stones. One has heard of people failing to hit a haystack; what followed was rather on those lines. I imagine Mrs Pankhurst had not played ball games in her youth, and the first stone flew backwards out of her hand, narrowly missing my dog. Once more we began at a distance of about three yards, the face of the pupil assuming with each failure -and there were a good many -a more and more ferocious expression. And when at last a thud proclaimed success, a smile of such beatitude - the smile of a baby that has blown a watch open - stole across her countenance, that much to her mystification and rather to her annoyance, the instructor collapsed on a clump of heather helpless with laughter.

Alas! the lesson availed nothing! The Downing Street window selected by Mrs Pankhurst was duly bombarded - I think she had two shots at it before they arrested her - but the stones never got anywhere near the objective. I broke my window successfully and was bailed out of Vine Street at midnight by wonderful Mr Pethick-Lawrence, who was ever ready to take root in any police station, his money bag between his feet, at any hour of the day or night.

The subsequent trial I thoroughly enjoyed and rather fell in love with our Judge, Sir Rufus Isaacs, in whose eye I detected a gleam of amused sympathy. At one moment he nearly got me into a hole and I was electrified by the way Mrs Pankhurst sprang up and with a lightning leading question showed me the way out. Thus might an experienced fish with a swish of its tail sweep a novice away from the mouth of the net. But Mrs Pankhurst declared it was far too simple a matter to make such a fuss about, and I dare say it was, to such as her.

The ensuing two months in Holloway, though one never got accustomed to an unpleasant sensation when the iron door was slammed and the key turned, were as nothing to me because Mrs Pankhurst was in with us. The merciful matron put us in adjoining cells, and at exercise, in chapel and on such other occasions as a kind-hearted matron can make for a prisoner, we saw more of each other than the protocol permitted. For instance she would often leave us together in Mrs Pankhurst's cell at tea-time 'just for a moment', lock us in, and forget to come back and conduct me to my own. But, as with policemen and detectives, Mrs Pankhurst refused to be softened by these favours, or by obviously sincere protestations of the 'it-hurts-me-more-than-it-hurts-you' order. And when, with an accent of cold scorn, she said, 'I would throw up any job rather than treat women as you say it is your didy to treat us,' the worst of it was that everyone knew this was nothing but the truth.

(17) Ethel Smyth, Female Pipings for Eden (1933)

I have often reflected that during those two months in Holloway for the first and last time of my life I was in good society. Think of it! more than a hundred women parked together, old and young, rich and poor, strong and delicate, one and all divorced from any thought of self, careless as to consequences, forgetful of everything save the idea for which they had faced imprisonment. Among them were elderly gentlewomen - Mrs Brackenbury was seventy-eight! - unfit for the rigours of prison life; young professional women who were deliberately snapping in two a promising professional career, made possible by God knows what heavy sacrifices; countless poor women of the working class, nurses, typists, shop-girls and the like, who had good reason to doubt whether their employers would ever take them back again. But of that they never spoke, perhaps never even thought, in Holloway. No wonder if some of us look back on that time with thankfulness and with awe, for where else on earth could we have scraped acquaintance with the Spirit that in those days had pitched her tent in Holloway Prison?

Meanwhile things had been going on from bad to worse. The so-called 'Cat and Mouse' Act, of which the murderous, cowardly, pseudo-humane refinement is to my mind more revolting than any torture invented in the Middle Ages, was now in full swing. The authorities dared not let the women die, so would release them, sometimes half-dead, to be rearrested as soon as they were judged fit to serve the remainder of their sentence. Whereupon the whole hideous business would begin again, the idea being that by degrees bodies and wills would be broken past mending. How a group of civilized Christian men could lend themselves to this proceeding rather than perform a simple act of justice already fifty years overdue is inconceivable - but so it was.

In April 1913 Mrs Pankhurst was once more arrested, and embarked on a hunger and thirst strike. Years afterwards she found among old papers, and gave me, two bescribbled little cards dated 9 April 1913, written on the ninth day of this ordeal which she believed she would not survive. The matron had mercifully put her in the charge of a wardress she was much attached to, and to her these farewell lines were secretly confided, to be posted to me in case of her death.

When hunger-striking she always refused with such terrible violence - mainly I think from personal fastidiousness and sense of dignity - to be forcibly fed, that no doctor dared attempt it, and in this little scrawl her handwriting is, if anything, more legible than usual, as if to show me her will was unbroken. She begs that in case of her death the old invalid mother of her dear wardress, Miss Harper, may be looked after. The next day she was let out and the wardress gave her back the letter; after which she forgot all about it, including her intention of destroying it; and not till nine years afterwards did I even know it had been written! The whole incident is typical of this strange woman, who lived less in the past and more wholeheartedly in the present and future than any one I have ever known.

(18) Ethel Smyth, Female Pipings for Eden (1933)

In 1915 I joined one of my sisters on the Italian front, returning to Paris to pass my examination as radiographer, and eventually got attached to the XIllth Division of the French army as voluntary 'localizer' in the huge hospital at Vichy.

Mrs Pankhurst meanwhile was addressing recruiting meetings in Trafalgar Square and all over the country, going later to Wales where there was much unrest and a constant threat of strikes among the miners. Her letters exude fury at the pacifist activities of some former militants in America, particularly of a certain childless couple who had declared England was 'decadent' and that they meant to live in America. 'Decadent indeed!' she remarks. 'Well, it comes badly from them to talk about decadence - married people who have failed in the real purpose of marriage!' (A very Pankhurstian gibe!)

Early in January 1918 the vote was at last given to women, and as Mrs Pankhurst remarked, we all took it very quietly, being under the shadow of the war. At that time I was still in France, and after the pushing back of the British line in March 1918, it was only with difficulty that I managed to get back to England. In April I saw Mrs Pankhurst fresh from Manchester, where the day before she had addressed four open-air meetings of munition workers and others. She was very tired but once more glorying in the loyalty of the women, who she told me were disgusted with the men. In some places, not daring because of public feeling to strike openly, these men, so the women informed her, were having what they called 'indoor strikes', i.e. working, but carefully doing exactly a quarter of what might be done in the day. She told me the whole 'skilled labour' cry was rubbish; there was nothing in it that any woman could not learn in three weeks; only the duty, have nothing to retract or regret, and should do the same in a similar case.

(19) Ethel Smyth, Female Pipings for Eden (1933)

One day, towards the end of 1925, to my great surprise I got a letter from her announcing that she was in London, staying with her sister Mrs Goulden-Bach. I went there to see her and learned that Christabel and their old WSPU friend Mrs Tuke had embarked on what looked like, and eventually turned out to be, a wild scheme for starting a teashop at Antibes. Mrs Pankhurst had just come from there, said it was more bitterly cold than words could say (it was a very hard winter everywhere), and I had a distinct impression that the other two had wanted to get rid of her while they were settling in.

My only feeling on seeing her again was... that I didn't really want to resume relations, for between us lay a silence - the subject of the breach. It was then I learned what doubtless many people are aware of, that when a profound and warm relation comes to what may be called an unnatural end, it can attain a quite surprising degree of deadness. How Mrs Pankhurst felt about it I do not know; but it was not given to her to form new ties, and I think she would have liked us to be on affectionate terms. Alas, I had nothing to give! This she felt, and it made her shy and uncertain in her manner... which again made my manner grim. Result: little American laughs and increased shyness on her side; no little laughs whatever and increased grimness on mine. And when the visit was over I was glad, realizing with a sort of macabre amusement how much more comfortable I was talking to her sister than to her! Looking back into the past one often savs to oneself, 'if that time could come again, 1 wonder if I should be less hard and uncompromising than I was then?'

(20) Fran Abrams, Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003)

In the summer of 1910 Emmeline was introduced to Ethel Smyth, an endearingly eccentric bisexual composer who cheerfully confessed to having little or no political background and to caring even less about votes for women - until she met and fell passionately in love with the founder of the WSPU. At first glance Ethel Smyth made a curious companion for a political leader who, despite the violence which attached itself to her movement, remained resolutely feminine. While Emmeline usually had some lace about her person Ethel always dressed in tweeds, deerstalker and tie. Emmeline tended to attack every venture with passion while her new friend regarded the world with a wry, amused cynicism. Ethel, unlike Emmeline, had few sexual or personal inhibitions. But the two women, who at fifty-two were exactly the same age, immediately formed so close an attachment that Ethel decided to give two years of her life to the cause. After that, she said, she would go back to her music. She was as good as her word, though the friendship endured even after she had left the political fray. Ethel's insights into the mind of her friend are incisive and enlightening, untainted by the family tensions which strained the memoirs of the younger generation of Pankhursts. Although it is clear from her writing that her admiration for Emmeline Pankhurst went much further than mere political esteem or platonic affection, it seems unlikely the relationship was a physical one. As Smyth herself noted, her friend had rarely if ever formed close attachments to other women in the past and, if anything, preferred friendships with men.

(21) Rebecca Jennings, A Lesbian History of Britain (2007)

The WSPU attracted a high proportion of single women, with almost all the full-time organisers and 63 per cent of those making donations in 1913-1914 being unmarried. For some single women who were attracted to other women, such as the suffragette Micky Jacob, the movement encouraged them to consider new options: "Looking back, I think that the Suffragettes helped me to - get free. I met women who worked, women who had ambitions, and some who had gratified those ambitions. I looked at my own position, and began to think and think hard." (Me: A Chronicle About Other People, 1933)

Others met partners and lovers through the movement. The composer Ethel Smyth, who contributed the suffrage anthem, The March of the Women, was well known for her attraction to other women and may have had an affair with Emmeline Pankhurst. Edy Craig and Christopher St John (Christabel Marshall), who lived together for forty-eight years from 1899 until Edy's death, were also active in the WSPU.