Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

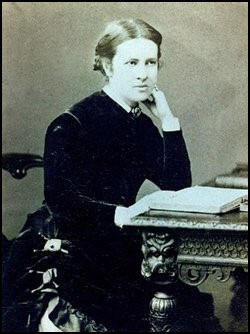

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the daughter of Newson Garrett (1812–1893) and Louise Dunnell (1813–1903), was born in Whitechapel, London on 9th June 1836. Elizabeth's father, was the grandson of Richard Garrett, who founded the successful agricultural machinery works at Leiston. (1)

"The Garretts were a close and happy family in which children were encouraged to be physically active, read widely, speak their minds, and share in the political interests of their father, a convert from Conservatism to Gladstonian Liberalism, a combative man, and a keen patriot". (2)

Elizabeth's siblings included Louisa Garrett (1835-1867), Newson Garrett (1839–1917), Edmund Garrett (1840–1914), Alice Garrett (1842–1925), Agnes Garrett (1845–1935), Millicent Garrett (1847–1929), Samuel Garrett (1850–1923), Josephine Garrett (1852–1925) and George Garrett (1854–1929). (3)

Elizabeth's father had originally ran a pawnbroker's shop in London, but in 1838 he decided to return to the healthier climate of Suffolk. Three years later he purchased the Snape corn and coal merchant's business and shipping interests of Robert Fennel and settled his wife and young family at The Uplands, in Aldeburgh. Garrett's business grew fast. "Within three years he was sending about 17,000 quarters of barley to London and Newcastle. He was soon building his own barges and in 1848 was appointed agent for Lloyds. He constructed a gasworks, acquired a local brickworks and built numerous cottages. In 1852 he built Alde House, an impressive mansion overlooking the town of Aldeburgh (complete with ice-house and turkish bath), and two years later designed and built maltings at Snape Bridge. In 1859 the capacity of the maltings was doubled, and the adjoining Bridge House, the family's winter residence during the malting season, completed." (4)

Langham Place Group

Elizabeth was educated by a governess at home, from 1846. In 1849 Elizabeth and his sister, Louisa Garrett, at a boarding-school for ladies at Blackheath, which was run by Miss Louisa Browning, an aunt of the poet Robert Browning. (5) While the girls were at the school, they became friendly with two other pupils, Sophie and Annie Crowe. Their home was at Usworth and sometimes they spent part of their summer holidays there. On one of these visits they were introduced to Emily Davies, who at that time was one of the leading campaigners for women's rights. Davies also visited the Garrett family home in Aldeburgh: "She wanted women to have as good and thorough an education as men; she wanted to open the professions to them and to obtain for them the Parliamentary franchise. But she did not want any violence either of speech or action. She remained always the quiet, demure little rector's daughter, and she meant to bring about all the changes she advocated by processes as gradual and unceasing as the progress of a child from infancy to manhood." (6)

After two years at a school in Blackheath, Elizabeth Garrett was expected to stay in the family home until she found a man to marry. However, Elizabeth was more interested in obtaining employment. On 10th September 1857, her sister, Louisa Garrett married James William Smith and set up home in South Audley Street, Mayfair, London. (7)

Louisa Garrett Smith was a strong advocate of women's rights. In December 1859 she joined forces with Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies, Helen Blackburn,Barbara Bodichon, Sophia Jex-Blake, Frances Power Cobbe, Jessie Boucherett and Emily Faithfull to form the Langham Place Group. Davies refused to be secretary because she thought it was prudent to keep her own name "out of sight, to avoid the risk of damaging my work in the education field by its being associated with the agitation for the franchise." Louisa agreed to take on the role of secretary and be the organisation's figurehead. (8)

Elizabeth was therefore "at the core of the emerging mid-Victorian women's movement". (9) The group played an important role in campaigning for women to become doctors. They arranged for Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor, to give a lecture entitled, "Medicine as a Profession for the Ladies". In 1862 they formed a committee to campaign for women's entry for university examinations, initially in support of Elizabeth Garrett, in her application to matriculate at London University. (10)

Medical Training

Elizabeth Garrett developed a strong desire to become a doctor. As she told Elizabeth Blackwell: "At first he was very discouraging, to my astonishment then, but now I fancy he did it as a forlorn hope to check me; he said the whole idea was so disgusting that he could not entertain it for a moment. I asked what there was to make doctoring more disgusting than nursing, which women were always doing, and which ladies had done publicly in the Crimea. He could not tell me. When I felt rather overcome with his opposition, I said as firmly as I could, that I must have this or something else, that I could not live without some real work, and then he objected that it would take seven years before I could practise. I said if it were seven years I should then be little more than 31 years old and able to work for twenty years probably. I think he will probably come round in time, I mean to renew the subject pretty often." (11)

Millicent Garrett later commented: "I think the most remarkable thing he ever did was to give active help and support to my sister Elizabeth, then aged about twenty, to enter the medical profession: at the time, of course, all the usual methods of entering the profession were not only closed, but barred, banged, and bolted against women. These bars and bolts a young inexperienced girl, aided by her father, a country merchant, proposed to destroy and throw the gates open. My mother gave no help: she not only was unsympathetic, but intensely averse to the proposal." (12)

As Elizabeth Garrett pointed out in a letter to Emily Davies in August 1860, about her mother's unhappiness about her becoming a doctor: "I have had a letter from my mother… she speaks of my step being a source of life-long pain to her, that it is a living death, etc. By the same post I had several letters from anxious relatives, telling me that it was my duty to come home and thus ease my mother's anxiety." (13)

In July 1860, Newson Garrett agreed to financially support his daughter's attempts to become a doctor. Newson approached his friend, William Hawes, and asked him if he could arrange medical training for Elizabeth Garrett. Hawes advised Elizabeth to go into a surgical ward at the Middlesex Hospital for a preliminary period of six months. He could arrange this, he said. "It was to test her resolution that Mr. Hawes suggested a surgical ward where conditions at that time, even in the best hospitals, were bad. Mr. Hawes knew that the sights, sounds and smells in a surgical ward would provide a searching test." (14)

This experience did not dissuade Elizabeth. As Mary Ann Elston has pointed out: "Elizabeth Garrett applied to enroll formally as a medical student at several London teaching hospitals and to matriculate at the universities of Edinburgh, St Andrews, and London. All these attempts were unsuccessful except for a brief period in 1860–61 at the Middlesex Hospital in London, where pressure from some of the male students, possibly jealous of her academic prowess, led to her being excluded from further study there." (15)

Elizabeth Garrett did well at Middlesex Hospital. However, male students objected to her being on the course: "The presence of a young female in the operating theatre is an outrage to our natural instincts and is calculated to destroy the respect and admiration with which the opposite sex is regarded." Louisa Garrett Anderson pointed out: "Elizabeth obtained a certificate of honour in each class examination; she did so well indeed that the examiner in sending her the list added, 'May I entreat you to use every precaution in keeping this a secret from the students?' In June trouble arose. The visiting physician asked his class a question, none of the men could answer and Elizabeth gave the right reply. The students were angry and petitioned for her dismissal. A counter-petition was sent to the committee but she was told she would be admitted to no more lectures although she might finish those for which she had paid fees." (16)

Elizabeth Garrett discovered that the Society of Apothecaries did not specify that females were banned for taking their examinations. In 1865 Garrett sat and passed the Apothecaries examination. As soon as Garrett was granted the certificate that enabled her to become a doctor, the Society of Apothecaries changed their regulations to stop other women from entering the profession in this way. With the financial support of her father, Elizabeth Garrett was able to establish a medical practice in Upper Berkeley Street, London. (17)

Political Activity

In 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. One of the founders of the group was Alice Westlake. On 18th March, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse." (18)

Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. The group had around fifty members, including Elizabeth Garrett, Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Anne Clough, Alice Westlake, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy. (19)

The women often met in the house of Elizabeth Garrett. The women decided to draft a petition that would be presented by John Stuart Mill to the House of Commons. By the beginning of June 1866 they had almost 1,500 signatures (all women). On 7th June, Eizabeth Garrett and Emily Davies, escorted the great scroll to Westminster Hall. Mill, said, "Ah! this I can brandish with effect." (20)

In 1866, supported by some prominent philanthropists as patrons, she established the St Mary's Dispensary for Women and Children, in the Marylebone district of London, and a provident fund for poor women seeking her services. (21) By 1869 her private practice had grown considerably, however a vacancy occurred on the honorary medical staff of the Shadwell Hospital for Children (later the East London Hospital for Children) that she accepted. (22)

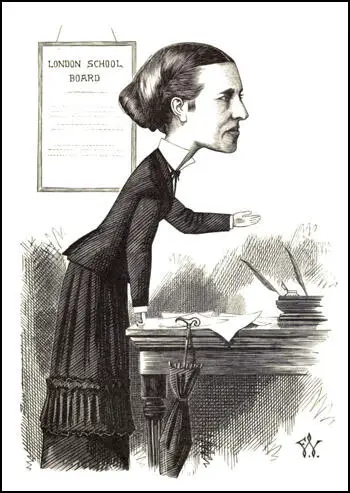

The 1870 Education Act allowed women to vote for the School Boards. Women were also granted the right to be candidates to serve on the School Boards. Several feminists saw this as an opportunity to show they were capable of public administration. In 1870, four women, Elizabeth Garrett, Lydia Becker, Emily Davies and Flora Stevenson, were elected to local School Boards. As Ray Strachey, pointed out in her book, The Cause: A Short History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain (1928): "Miss Garrett secured a larger majority than any of the other Londoners or then any municipal candidates had ever had before, winning 47,858 votes in spite of the fact (or perhaps because of the fact) that she was by that date that most alarming and outrageous thing, a female medical practioner." (23)

The chairman of her election campaign was James George Skelton Anderson (1838–1907), co-owner of the of the Orient Steamship Company, and the financial adviser to the East London Hospital. married Elizabeth Garrett on 9th February 1871. They had one son, Alan Garrett Anderson, and two daughters, Margaret, who died of meningitis in 1875, and Louisa Garrett Anderson, who went on to become a doctor. Marriage and motherhood did not apparently impede the development of Garrett Anderson's successful medical career. (24)

Contagious Diseases Act

Several of the women who were demanding the vote, including Elizabeth's cousin, Rhoda Garrett, were opposed to the Contagious Diseases Acts. These acts had been introduced in the 1860s in an attempt to reduce venereal disease in the armed forces. Under the terms of these acts, the police could arrest women they believed were prostitutes and could then insist that they had a medical examination. Many of the women were not prostitutes but they still had to undergo the medical examination. (25)

Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy and Josephine Butler objected in principal to laws that only applied to women. They also had considerable sympathy for the plight of prostitutes who they believed had been forced into this work by low earnings and unemployment. In December 1869, Wolstenholme-Elmy and Butler formed the Ladies Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts: "These Acts are in force in some of our garrison towns unlike all other laws for the repression of contagious diseases, to which both men and women are liable, these two apply to women only, men being wholly exempt from their penalties. Equality before the law, even for fallen women. Let your laws be put in force, but let them be for male and female." (26)

The petition calling for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts had 2,000 signatures, including those of Rhoda Garrett, Louisa Martindale, Florence Nightingale and Lydia Becker. Most of the newspapers were hostile to this campaign. Martineau commented: "The extraordinary violence and ill manners of the Pall Mall Gazette and some other papers seem to me to indicate that they think our cause is gaining ground." (27)

Elizabeth Garrett, the only British woman qualified as a doctor at that time, not only supported the Contagious Diseases Acts but also their extension to civilian areas. In a letter to the British Medical Journal, Elizabeth Garrett argued that only doctors could really understand the need to contain syphilis: "Miss Nightingale and her coadjutors' should leave well alone, since only men, with the rarest exceptions had any hope of understanding it." (28)

Medical Career

In 1870 Garrett supplemented her relatively low-status qualification with an MD (Medicinae Doctor) from the University of Paris, the first woman to obtain this degree. Sophia Jex-Blake and the other six women training to be doctors in Edinburgh sent her a letter of congratulations: "Our hearty congratulations on the brilliant success at Paris which has at length crowned your many years of arduous work - work whose difficulties perhaps no one can estimate so well as ourselves. And while congratulating you on receiving the highest honour of your profession from one of the finest medical schools in the world, we desire to express also our appreciation of the example you have afforded to others, and the honour you have reflected on all women who have chosen medicine as their profession." (29)

In 1871 Garrett Anderson opened ten beds above the dispensary as the New Hospital for Women in London. This was to be the first hospital in Britain with only medical women appointed to its staff. Initially, and perforce, Garrett Anderson appointed unregistered women with overseas medical degrees as house officers. Elizabeth Blackwell, the woman who inspired her to become a doctor, was appointed professor of gynecology. (30)

Mary Ann Elston points out that it was not seen as acceptable for women doctors to carry out operations: "In 1872 her decision to undertake the then high risk procedure of ovariotomy herself for the first time led to the resignation of her house officer, Frances Hoggan, and the refusal by the hospital's management committee to have the operation performed on the premises. (The operation eventually took place in rented premises and the patient survived.)" (31)

In 1873 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was surprisingly admitted to membership of the British Medical Association (BMA). It received very little publicity at the time and criticism of the admission of women to the BMA was first voiced at the annual general meeting in Edinburgh in 1875 and in 1878 the BMA voted against the admission of further women and she remained the only woman member for nineteen years. (32)

In 1874 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson joined with Sophia Jex-Blake, Emily Blackwell and Elizabeth Blackwell to establish a London Medical School for Women. Jex-Blake expected to put in charge but Garrett believed that her temperament made her unsuitable for the task and arranged for Isabel Thorne to be appointed instead. To her students Garrett Anderson offered a model of female professionalism in which "the first thing women must learn is to dress like ladies and behave like gentlemen". (33) In 1883 Garrett Anderson was elected Dean of the London School of Medicine. Sophia Jex-Blake was the only member of the council who voted against this decision. (34)

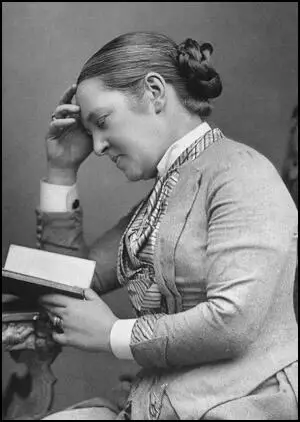

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson continued to provide free medical treatment for the poor but by 1885 had built up a successful private practice, comparable to that of leading male doctors. She believed that prevention was better than cure, and her bedside manner was reported as being like her natural manner in private, "dry, witty and often brusque. Her will was indomitable and she never suffered fools gladly". (35)

Women's Suffrage

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson made her first public speech for enfranchisement in 1868. However, unlike her sisters, Louisa Garrett Smith, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, and Agnes Garrett did not play an active role in the campaign but was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), an organization that her sister, Millicent, was elected president on 14th October 1897. (36)

According to her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, there was a good reason why she did not play a significant role in the campaign for women's suffrage: "She did not speak at suffrage meetings nor take a prominent part in the organization, thinking "it would be unwise to be identified with a second unpopular cause. Nevertheless she gave her whole-hearted adherence." (37)

In 1902 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson retired to Aldeburgh. Garrett Anderson continued her interest in politics and in 1908 she was elected mayor of the town - the first woman mayor in England. When Garret Anderson was seventy-two, she became a member of the militant Women's Social and Political Union. This caused great distress to her sister, Millicent Garrett Fawcett. (38)

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson took part in Suffrage Saturday on 13th June 1908. It is estimated that 10,000 women led by the National Union for Women’s Suffrage Societies marched through central London, demonstrating the volume of women that supported their cause. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Emily Davies and Hertha Ayrton marched at the head of the professional women and graduates section. (39) Later that year she was lucky not to be arrested after she joined with other members of the WSPU to storm the House of Commons. (40) In October 1909 she went on a lecture tour with Annie Kenney. (41)

Black Friday

In January 1910, H. H. Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement". (42)

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) agreed to the idea and they declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. (43) Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated." (44)

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it. (45)

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson agreed to walk beside Pankhurst. Roger Fulford has pointed out: "This venerable but picturesque figure - she was seventy-four and wore a fur bonnet tied under the chin with white ribbons - was the epitome of Victorian feminism - sensible, dignified and attractive. Her prescence commanded the immediate respect and attention of the police who escorted the two ladies to the House of Commons." (46) Asquith refused to see Anderson and Pankhurst. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police. (47)

Sylvia Pankhurst later described what happened on what became known as Black Friday: "As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.... Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse." (48)

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson left the WSPU's in 1911 as she objected to their arson campaign. (49) Her daughter Louisa Garrett Anderson remained in the WSPU and in 1912 was sent to prison for her militant activities. Millicent Garrett Fawcett was upset when she heard the news and wrote to her sister: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does." (50)

Evelyn Sharp spent time with Elizabeth and Louisa Garrett Anderson at their cottage in the Highlands: "Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had a summer cottage in that beautiful part of the Highlands. I went there on both occasions with her daughter Dr. Louisa Garrett Anderson, and we had great times together climbing the easier mountains and revelling in wonderful effects of colour that I have seen nowhere else except possibly in parts of Ireland.... It was, however, so entertaining to meet both these famous public characters in the more intimate and human surroundings of a summer holiday that we did not grudge the time given to working up a suffrage meeting in the village instead of tramping about the hills. Old Mrs. Garrett Anderson-old only in years, for there was never a younger woman in heart and mind and outlook than she was when I knew her before the war was a fascinating combination of the autocrat and the gracious woman of the world." (51)

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson died in 17th December 1917.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1939, Louisa Garrett Anderson, the daughter of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, wrote about attitudes towards girls' education in the 19th century.

Men were believed to dislike "blue-stockings", so that parents thought the serious education of their daughters superfluous: deportment, music and a little French would see them through. 'To learn arithmetic will not help my daughter to find a husband was a common point of view. A governess at home, for a short period, was the usual fate of the girls. Their brothers might go to public schools and university but home was considered the right place for their sisters. Some parents sent their daughters to a finishing school, but good schools for girls did not exist. Their teachers were untrained and ill-educated. No public examinations accepted female candidates.

To his daughters, Newson Garrett opened up the windows of the world by sending them to boarding school… He took trouble in the choice of school. Finally it was decided that Louie and Elizabeth should go on to an 'Academy for the Daughters of Gentlemen' at Blackheath, kept by Miss Browning and her sister… After two years at Blackheath, Louie and Elizabeth left, their education considered to be at an end.

(2) In 1859, the 23-year-old, Elizabeth Garrett (Anderson), met Emily Davies when she was staying at Annie Crowe's house. Emily and Elizabeth became close friends. Emily told Elizabeth about how Elizabeth Blackwell had qualified as a doctor in the USA. With Emily's encouragement, Elizabeth decided that she would be a doctor. On 15th June 1860, Elizabeth wrote to Emily to tell her how her father had reacted to the news.

At first he was very discouraging, to my astonishment then, but now I fancy he did it as a forlorn hope to check me; he said the whole idea was so disgusting that he could not entertain it for a moment. I asked what there was to make doctoring more disgusting than nursing, which women were always doing, and which ladies had done publicly in the Crimea. He could not tell me. When I felt rather overcome with his opposition, I said as firmly as I could, that I must have this or something else, that I could not live without some real work, and then he objected that it would take seven years before I could practise. I said if it were seven years I should then be little more than 31 years old and able to work for twenty years probably. I think he will probably come round in time, I mean to renew the subject pretty often.

(3) Louisa Garrett Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1939)

Mr. Hawes advised Elizabeth to go into a surgical ward at the Middlesex Hospital for a preliminary period of six months. He could arrange this, he said. It was to test her resolution that Mr. Hawes suggested a surgical ward where conditions at that time, even in the best hospitals, were bad. Mr. Hawes knew that the sights, sounds and smells in a surgical ward would provide a searching test. In 1860 bacteriology was in its infancy and the connection between living germs and wound infection had occurred to no one. The mortality after major operations was appalling, and even in trivial cases infection might occur. For ward visits a frock-coat was worn and for the coat's sake it was exchanged for an old one before the surgeon entered the theatre. Usually he washed his hands after operating, not necessarily before. Gloves were not worn. Sterilization of ligatures and instruments was unknown.

(4) In 1863 male doctors at Middlesex Hospital issued a statement on the subject of women doctors.

The presence of a young female in the operating theatre is an outrage to our natural instincts and is calculated to destroy the respect and admiration with which the opposite sex is regarded.

(5) While Elizabeth Garrett was training at Middlesex Hospital she constantly received letters asking her to give up her plans to become a doctor. Elizabeth wrote about this pressure to Emily Davies on 17th August 1860.

I have had a letter from my mother… she speaks of my step being a source of life-long pain to her, that it is a living death, etc. By the same post I had several letters from anxious relatives, telling me that it was my duty to come home and thus ease my mother's anxiety.

(6) Louisa Garrett Anderson describes her mother's progress in 1861 at Middlesex Hospital in her book Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. page 80

Elizabeth obtained a certificate of honour in each class examination; she did so well indeed that the examiner in sending her the list added, 'May I entreat you to use every precaution in keeping this a secret from the students?' In June trouble arose. The visiting physician asked his class a question, none of the men could answer and Elizabeth gave the right reply. The students were angry and petitioned for her dismissal. A counter-petition was sent to the committee but she was told she would be admitted to no more lectures although she might finish those for which she had paid fees.

(7) In July 1863, Elizabeth Garrett applied to Aberdeen Hospital for medical training. On 29th July the hospital replied to her request.

I must decline to give you instruction in Anatomy… I have a strong conviction that the entrance of ladies into dissecting-rooms and anatomical theatres is undesirable in every respect, and highly unbecoming… it is not necessary for fair ladies should be brought into contact with such foul scenes… Ladies would make bad doctors at the best, and they do so many things excellently that I for one should be sorry to see them trying to do this one.

(8) After Elizabeth Garrett qualified as a doctor in 1865 she established a dispensary in London. Lord and Lady Amberley met Elizabeth at John Stuart Mill's home in Blackheath. Lady Amberley recorded the meeting in her diary.

We dined at six (excellent dinner) delightful general talk, it was most pleasant. The talk was of Comte, George Eliot and her new book Felix Holt… on Herbert Spencer's theory of the sun coming to an end and losing all its force.

At ten John Stuart Mill sent us and Miss Garrett home in his carriage and we had a nice talk on the way home. Her dispensary opens next week. She had much difficulty in becoming a doctor from want of facility for women to learn. She would not mind attending men but does not do it, on account of what would be said. We got home at eleven having enjoyed our day immensely.

(9) Elizabeth Garrett finally received her medical degree by taking an examination at Paris Medical School. On 20th June 1870 she received a letter of congratulations from Sophia Jex-Blake and the other six women training to be doctors in Edinburgh.

Our hearty congratulations on the brilliant success at Paris which has at length crowned your many years of arduous work - work whose difficulties perhaps no one can estimate so well as ourselves. And while congratulating you on receiving the highest honour of your profession from one of the finest medical schools in the world, we desire to express also our appreciation of the example you have afforded to others, and the honour you have reflected on all women who have chosen medicine as their profession.

(10) Evelyn Sharp, Unfinished Adventure (1933)

There were occasional, very occasional, holidays at home during the years of the suffrage agitation. Two that stand out especially in my memory were spent at Newtonmore in Inverness-shire. Here I was the guest of Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had a summer cottage in that beautiful part of the Highlands. I went there on both occasions with her daughter Dr. Louisa Garrett Anderson, and we had great times together climbing the easier mountains and revelling in wonderful effects of colour that I have seen nowhere else except possibly in parts of Ireland. Only those who were engulfed in the preoccupations of those militant years could appreciate what it meant to us to get away from it all for a week or two, although our peace was twice invaded by the campaign we thought we had left behind, when Mrs. Fawcett (my hostess's sister) and Mrs. Pankhurst stayed with us, each in the course of conducting a speaking tour. It was, however, so entertaining to meet both these famous public characters in the more intimate and human surroundings of a summer holiday that we did not grudge the time given to working up a suffrage meeting in the village instead of tramping about the hills.

Old Mrs. Garrett Anderson-old only in years, for there was never a younger woman in heart and mind and outlook than she was when I knew her before the war was a fascinating combination of the autocrat and the gracious woman of the world. I thought one of her brothers summed her up rather delightfully, one day, when, contrary to everybody's entreaties and advice, she insisted on clambering down a steep incline under the unshakable impression that it was a short cut home. "You must make allowances, I suppose, for her being the first woman doctor," he observed, when she had had time to realise her error and he was setting off to fetch her back. Undoubtedly, like Florence Nightingale and other reformers who have had to fight both prejudice and vested interests, if Elizabeth Garrett Anderson had been the sweetly reasonable person who always believes what she is told without questioning it, she would not have been the pioneer who opened the medical profession to women. In her own home she was a most hospitable and lovable hostess, and had a delicious sense of humour, which may have been one reason why she was instantly attracted towards the militant branch of the suffrage movement when it became prominent. Her daughter, who brought the same gifts of courage and perception, so rare in combination, to the service of the same cause, inherited all her mother's brains and culture, and more than her personal charm and gentleness. Her friendship was one of those I gained at that troublous time, and it offered generous compensation for many losses.

There was a strong family likeness in all the Garretts ; and their fine sterling qualities, added to much that was personally attractive, made me feel proud to be a member of the house party that included three of the sisters of the older generation. Miss Agnes Garrett used to accompany Mrs. Fawcett everywhere, and when they both joined us at Newtonmore, the conversation became noticeably more racy, enlivened as it was with many excellent anecdotes gathered in their wanderings about the world. Nothing seemed to daunt these doughty women, and although I have always rather prided myself on wearing suitable clothes and yielding easily to the demands of a simple country life, I felt nothing but an artificial inhabitant of cities when I saw them tuck up their skirts - there was plenty to tuck up in those days - and don indescribable boots, before starting out to brave inclement weather and face really difficult rambles in the mountains above Speyside. I wondered sometimes if, thirty or forty years later, I should be able at the same age to show half their energy and unassailable good health.