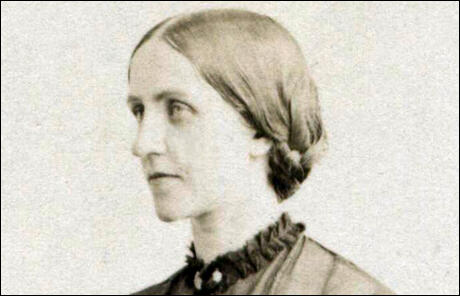

Dorothea Beale

Dorothea Beale, the daughter of Miles Beale and Dorothea Complin, was born in London on 21st March, 1831. Miles Beale, a surgeon, employed a governess for Dorothea and her ten brothers and sisters. At sixteen Dorothea was sent to a school in Paris for a year.

Dorothea became a student at Queen's College for Women when it first opened in 1848. Dorothea did so well that when she finished her studies they appointed her as their first woman mathematics tutor. However, Dorothea gradually became dissatisfied with the college and in 1856 became Head Teacher at Casterton School. Attempts to make changes to the way the school was organised ended in failure and she left within a year of being appointed.

For the next twelve months she concentrated on writing a Textbook of General History. This became a popular book with teachers and helped her to be appointed as Head Teacher of Cheltenham Ladies College. At the time the school had only a moderate reputation but under Beale's leadership it became one of the most highly regarded schools in the country. The traditional education of girls had emphasized the development of accomplishments such as music and drawing. Dorothea Beale, however, was determined to provide a much more academic education.

Dorothea used her success at Cheltenham Ladies College to demonstrate what a good school could achieve. Dorothea Beale was also involved in trying to improve the national standard of education and played a prominent role in the Head Mistresses' Association and The Teachers' Guild.

In 1865 Dorothea Beale joined with Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett and eight other women to form a discussion group called the Kensington Society. In 1867 the group drafted a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote. One of their supporters, John Stuart Mill, added an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men. However, the amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Dorothea Beale eventually became vice-president of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage.

In 1892 Dorothea Beale purchased Cowley House in Oxford for £5,000. The following year, the building was opened as St. Hilda's College. In 1897 St. Hilda's was accepted by the Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women as a high standard college for women.

Beale wrote several books about education including Work and Play in Girls' Schools (1898). Dorothea Beale continued as the principal of Cheltenham Ladies College until her death on 9th November 1906.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1840 Dorothea Beale's mother decided it was time that her nine-year-old daughter had a governess. Dorothea Beale described how her mother approached the problem in her autobiography.

My mother advertised and hundreds of answers were sent. She began by eliminating all those in which bad spelling occurred (a proceeding, which as a spelling reform I must now condemn), next the wording and composition were criticised, and lastly a few of the writers were interviewed and a selection was made. But alas! An inspection was made of our exercise-books revealed so many uncorrected faults, that a dismissal followed, and another search resulted in the same way. I can remember only one really clever and competent teacher; she had been educated in a good French school.

(2) Mrs. Beale was unable to find a good governess and eventually Dorothea was sent away to school. She described her experiences in her autobiography.

It was a school considered much above average for sound instruction; our mistresses had taken pains to arrange various schemes of knowledge; yet what miserable teaching we had in many subjects; history was learned by committing to memory little manuals; rules of arithmetic were taught, but the principles were never explained. Instead of reading and learning the masterpieces of literature, we repeated week by week the 'Lamentations of King Hezekiah', the pretty but somewhat weak 'Mother's Picture'.

Ill-health compelled me to leave at thirteen, and then began a valuable time of education under the direction of myself, during which I expended a great deal of energy in useless directions, but gained more than I should have probably done at any existing school. I had access to two large libraries; the London Institution and Crosby Hall; besides which the Medical Book Club circulated many books of general interest, which were read by all and talked over at meal-times and in the evening, when my father used often to read aloud to us.

(3) Rev. John Maurice, the founder of the Christian Socialist movement, was a great supporter to women's education. In 1848 he became the first head of Queen's College in Harley Street, a new training school for women teachers. The first group of students included Dorothea Beale, Sophia Jex-Blake and Frances Mary Buss. In his inaugural lecture Rev. John Maurice explained his ideas on teaching.

The vocation of a teacher is an awful one… she will do others unspeakable harm if she is not aware of its usefulness… How can you give a woman self-respect, how can you win for her the respect of others… Watch closely the first utterances of infancy, the first dawnings of intelligence; how thoughts spring into acts, how acts pass into habits. The study is not worth much if it is not busy about the roots of things.

(4) After a year studying at Queen's College, Dorothea Beale was asked to become one of the maths tutors. In 1856 Dorothea Beale applied to become Head Teacher at Casterton School in Westmoreland. Queen's College was willing to give Dorothea Beale a good reference.

Miss Beale is a young lady of high moral and religious character, sober-minded and discreet. Her parents have been careful to avoid party views, and I have no doubt Miss Dorothea Beale is free from them. She certainly is a conscientious person, with a deep sense of her religious responsibilities. I feel certain that her influences will always be good.

(5) Cheltenham Ladies College was open in February 1854. The first report issued by the governors revealed that the school intended to prepare the girls for future duties.

The school intends to provide an education based upon religious principles which, preserving the modesty and gentleness of the female character, should so far cultivate a girl's intellectual powers as to fit her for the discharge of those responsible duties which devolve upon her as a wife, mother and friend, the natural companion and helpmate for man.

(6) A former pupil of Cheltenham Ladies College, wrote to Dorothea Beale about her experiences at the school in the 1850s.

The few months during which I was under your tuition more than fifty years ago were an epoch to me. Young as I was, I ever afterwards judged teaching by the standard set by yours, and very seldom indeed, I may truly say, has it been subsequently reached. The fifty years that have since passed, full as they have been, have never effaced the impression they received, both of your teaching and of something more comprehensive than your teaching, which contact with you engendered, and which impels me to take this opportunity - late in the day as it is - to express and to thank you for.

(7) In 1866 Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale organised a petition in favour of women's suffrage. Louise Garrett Anderson explained what happened on the day the petition was presented to Parliament.

John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… On 7th June 1866 the petition with 1,500 signatures was taken to the House of Commons. It was in the name of Barbara Bodichon and others, but some of the active promoters could not come and the honour of presenting it fell to Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett…. Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again.