Kensington Society

In May 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. It's founder members were the same women who formed the Langham Place Group and had been involved in the married women's property agitation and who had struggled to open local education examinations to girls. (1)

Membership was by personal invitation. The secretary, Emily Davies, brought together women "having more or less common interests and aims". Many were already friends, or were relatives of members. Others had been involved in the English Woman's Journal and had supported the campaign to open the Cambridge University local examinations to girls in 1864. Some met and shared ideas at the society for the first time. (2)

One of the founders of the group was Alice Westlake. On 18th March, 1865, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." (3) Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse." (4)

The Kensington Society had about fifty members, including Barbara Bodichon (artist), Jessie Boucherett (writer), Emily Davies (educationalist), Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Frances Power Cobbe (journalist), Anne Clough (educationalist), Alice Westlake (artist), Helen Taylor (educationalist), Elizabeth Garrett (medical student), Sophia Jex-Blake (medical student), Bessie Rayner Parkes (writer), Katherine Hare (educationalist) and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy (headmistress). (5)

Members of the Kensington Society were united by the opportunity to debate issues in a private, yet formal, setting. The women wanted practice in formal debating to build confidence for future public speaking. Some of the subjects discussed included: "What are the tests of originality?", "Is it desirable to employ emulation as a stimulus to education?" and "What form of government is most favourable to women?" In November 1865 the question was debated: "Is the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" (6)

Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. (7) Ann Dingsdale points out: "The annual subscription was half a crown. Questions for debate were issued four times a year and members might speak at meetings or submit written answers. Corresponding members submitted papers that were discussed by those who could attend (and who paid a further half-crown for that privilege). By conducting its debates in a private arena, with apparently unminuted discussions, the society encouraged a frank exchange of views." (8)

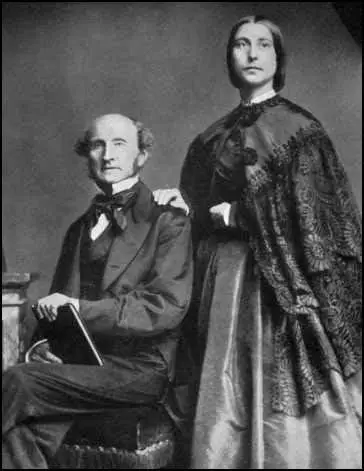

Helen Taylor was an important member of the Kensington Society because she was the step-daughter of John Stuart Mill, a philosopher who fully supported women's suffrage. In an article published in 1861 he argued: "In the preceding argument for universal, but graduated suffrage I have taken no account of difference of sex. I consider it to be as entirely irrelevant to political rights, as differences in height, or in the colour of the hair. All human beings have the same interest in good government; the welfare of all is alike affected by it, and they have equal need of a voice in it to secure their share of its benefits. If there be any difference women require it more than men, since being physically weaker, they are more dependent on law and society for protection." (9)

John Stuart Mill was invited by the Liberal Party to stand for the House of Commons in the 1865 General Election for Westminster. The Kensington Society saw this as an opportunity to promote the campaign for women's suffrage. In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Mill's step-daughter, Helen Taylor: "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time... Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately." (10)

Helen Taylor replied the same day: "It seems to me that while a Reform Bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from different classes - asking for representation or protesting against disenfranchisement should say so, and that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so, and that women not saying so now will be used against them in the future and delay the time of their enfranchisement.... I think the most important thing is to make a demand and commence the first humble beginnings of an agitation for which reasons can be given that are in harmony with the political ideas of English people in general. No idea is so universally accepted and acceptable in England as that taxation and representation ought to go together, and people in general will be much more willing to listen to the assertion that single women and widows of property have been overlooked and left out from the privileges to which their property entitles them, than to the much more startling general proposition that sex is not a proper ground for distinction in political rights." (11)

Helen Taylor stated that "If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up" her father would be willing to present it to Parliament." Two days later Barbara Bodichon replied that a small group including herself, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Elizabeth Garrett and Jessie Boucherett, had already started collecting signatures. (12) On receiving Taylor's draft petition, Bodichon commented it was too long and "it would be better to make it as short as possible and to state as few reasons as possible for what we want, everyone has something to say against the reasons." (13)

On 20th May 1867, Mill made a speech in the House of Commons where he proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together." (14)

In less than a month the Kensington Society collected nearly 1,500 signatures (one important member, Dorothea Beale, refused to sign the petition. Helen replied when it was delivered: "My father will present the petition tomorrow (if that is still the wish of the ladies) and it should be sent to the House of Commons to arrive there before two p.m. tomorrow, Thursday June 7th directed to Mr Mill, and petition written on it. It is indeed a wonderful success. It does honour to the energy of those who have worked for it and promises well for the prospects of any future plan for furthering the same objects." (15)

On 7th June, 1867 Barbara Bodichon was ill and so Elizabeth Garrett and Emily Davies, escorted the great scroll to Westminster Hall and gave their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Mill, said, "Ah! this I can brandish with effect." (16) Louisa Garrett Anderson later recalled: "John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again." (17)

hiding first women’s suffrage petition under an apple-woman’s stall in Westminster Hall

until John Stuart Mill came to collect it.

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment to the 1867 Reform Act was defeated by 196 votes to 73. William Gladstone, was one of those who voted against the amendment. (18)

The Enfranchisement of Women Committee was established in October 1866. Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed by the result of the House of Commons vote and they decided to dissolve the organisation early in 1868 and to establish the London Society for Women's Suffrage with the sole purpose of campaigning for women's suffrage. (19) Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. (20)

Primary Sources

(1) Alice Westlake, letter to Helen Taylor (20th March, 1865)

There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse.

(2) Barbara Bodichon, letter to Helen Taylor (9th May, 1866)

I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time. I have only just arrived in London from Algiers but I have already seen many ladies who are willing to take some steps for this cause. Miss Boucherett who is here puts down £25 at once for expenses. I shall be every day this week at this office at 3 p.m. Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately.

(3) Helen Taylor, letter to Barbara Bodichon (9th May, 1866)

It seems to me that while a Reform Bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from different classes - asking for representation or protesting against disenfranchisement should say so, and that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so, and that women not saying so now will be used against them in the future and delay the time of their enfranchisement.... I think the most important thing is to make a demand and commence the first humble beginnings of an agitation for which reasons can be given that are in harmony with the political ideas of English people in general. No idea is so universally accepted and acceptable in England as that taxation and representation ought to go together, and people in general will be much more willing to listen to the assertion that single women and widows of property have been overlooked and left out from the privileges to which their property entitles them, than to the much more startling general proposition that sex is not a proper ground for distinction in political rights...

We should only be petitioning for the omission of the words male and men from the present act... If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up my father will gladly undertake to present it and will consider whether it might be made the occasion for anything further. He could at least move for a return of the number of householders disqualified on account of sex, which could be useful to us in many ways if it could be got. I shall be very glad to subscribe £20 towards expenses.

(4) In her book Women's Suffrage published in 1911, Millicent Garrett Fawcett described the organisation of a petition on women's suffrage.

In 1866 a little committee of workers had been formed to promote a parliamentary petition from women in favour of women's suffrage. It met in the house of Miss Elizabeth Garrett (now Mrs. Garrett Anderson) and included Mrs. Bodichon, Miss Emily Davies, Miss Rosamond Davenport Hill and other well-known women.

(5) Louisa Garrett Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1939)

John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… On 7th June 1866 the petition with 1,500 signatures was taken to the House of Commons. It was in the name of Barbara Bodichon and others, but some of the active promoters could not come and the honour of presenting it fell to Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett…. Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again.