Katherine Hare

Katherine Hare, the daughter of Mary Samson (1813-1855) and Sir Thomas Hare (1806-1891), was born at 1 Pelham, Place, Brompton, on 9 April 1843. She was the fourth of eight children: Marian (1839-1929), Sherlock (1840-1912), Alice (1842-1923), Lydia (1844–1937), Herbert (1847–1874), Alfred (1849–1903) and Lancelot (1851–1922). (1)

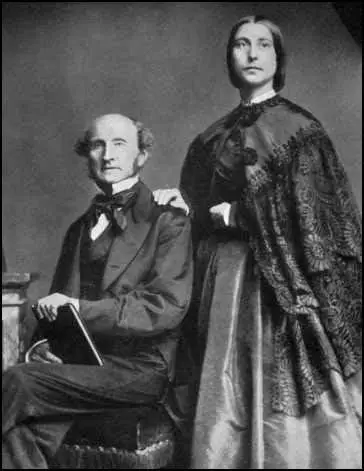

Thomas Hare was a legal scholar who devised a system of proportional representation of all classes and opinions in the United Kingdom, including minorities, in the House of Commons and other electoral assemblies. (2) Hare's suggested reforms were supported by Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill. Fawcett thought Hare's scheme offered "the only remedy against the great danger of an oppression of minorities". (3)

In 1851 Katherine Hare was living with her parents and siblings at Chestnut Cottage, Ham, Surrey. Her father, Thomas Hare, is described on the census return as a 45-year-old "Barrister in Practice." (4) On 21st October 1855, Alice’s mother, Mrs Mary Hare, died at the age of 42. (5)

In 1861, 18-year-old Alice Hare was residing with her widowed father and four of her siblings at Gosbury Hill, Hook, Surrey. On the census return, 55-year-old Thomas Hare is recorded as "Barrister not in actual practice" and as a "Charity Commissioner". Thomas Hare employed four domestic servants at his house in Hook. (6)

Kensington Society

In May 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. It's founder members were the same women who formed the Langham Place Group and had been involved in the married women's property agitation and who had struggled to open local education examinations to girls. (7)

Membership was by personal invitation. The secretary, Emily Davies, brought together women "having more or less common interests and aims". Many were already friends, or were relatives of members. Others had been involved in the English Woman's Journal and had supported the campaign to open the Cambridge University local examinations to girls in 1864. Some met and shared ideas at the society for the first time. (8)

One of the founders of the group was Katherine Hare's married sister, Alice Westlake. On 18th March, 1865, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." (9) Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse." (10)

Katherine Hare joined the Kensington Society. (11) It had about fifty members, including Barbara Bodichon (artist), Jessie Boucherett (writer), Emily Davies (educationalist), Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Frances Power Cobbe (journalist), Anne Clough (educationalist), Alice Westlake (artist), Helen Taylor (educationalist), Elizabeth Garrett (medical student), Sophia Jex-Blake (medical student), Bessie Rayner Parkes (writer) and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy (headmistress). (12)

Members of the Kensington Society were united by the opportunity to debate issues in a private, yet formal, setting. The women wanted practice in formal debating to build confidence for future public speaking. Some of the subjects discussed included: "What are the tests of originality?", "Is it desirable to employ emulation as a stimulus to education?" and "What form of government is most favourable to women?" In November 1865 the question was debated: "Is the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" (13)

Women's Suffrage

Katherine Hare campaigned with Emily Davies to extend the local examination system to girls. (14) John Stuart Mill was invited by the Liberal Party to stand for the House of Commons in the 1865 General Election for Westminster. Katharine and Alice saw this as an opportunity to promote the campaign for women's suffrage. In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Mill's step-daughter, Helen Taylor: "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time... Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately." (15)

Helen Taylor stated that "If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up" her father would be willing to present it to Parliament." Two days later Barbara Bodichon replied that a small group including herself, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Elizabeth Garrett and Jessie Boucherett, had already started collecting signatures. (16) On receiving Taylor's draft petition, Bodichon commented it was too long and "it would be better to make it as short as possible and to state as few reasons as possible for what we want, everyone has something to say against the reasons." (17)

In less than a month the Kensington Society collected nearly 1,500 signatures (one important member, Dorothea Beale, refused to sign the petition. Helen replied when it was delivered: "My father will present the petition tomorrow (if that is still the wish of the ladies) and it should be sent to the House of Commons to arrive there before two p.m. tomorrow, Thursday June 7th directed to Mr Mill, and petition written on it. It is indeed a wonderful success. It does honour to the energy of those who have worked for it and promises well for the prospects of any future plan for furthering the same objects." (18)

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment to the 1867 Reform Act was defeated by 196 votes to 73. William Gladstone, was one of those who voted against the amendment. (19)

hiding first women’s suffrage petition under an apple-woman’s stall in Westminster Hall

until John Stuart Mill came to collect it.

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to dissolve the organisation early in 1868 and to establish the London Society for Women's Suffrage with the sole purpose of campaigning for women's suffrage. (20)

London Society for Women's Suffrage

Clementia Taylor was the driving force behind the formation of the London Society for Women's Suffrage. From the outset it was intended that this new society in London was to be part of a federated scheme. Taylor wrote that she was willing "to undertake the secretary-ship of the London Central Committee the centres all to be affiliated together and in constant correspondence with each other so that no work shall be repeated. I think different centres will be necessary for local actions - but no centre to take any important step without reference to all the other centres." (21)

The first committee of the society included Katharine Hare, Frances Power Cobbe, Millicent Garrett Fawcett and Margaret Bright Lucas. Other members included Helen Taylor, Lydia Becker, Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Rhoda Garrett, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Louisa Garrett Smith, Priscilla McLaren, Elizabeth Garrett, Alice Westlake, Catherine Winkworth and Kate Amberley. (22)

Clementia Taylor took the main role in developing the strategy for the London Society for Women's Suffrage: "Our present course of action is the dissemination of information throughout the kingdom and it seems to me, we cannot apply our pounds to better purpose than by the publication of good papers." (23) This included Helen Taylor's pamphlet's The Claims of Englishwomen to the Suffrage Constitutionally Considered. (24)

The first public meeting organised by the London Society for Women's Suffrage was held in the Gallery of the Architectural Society in Conduit Street on 17th July 1869. The chair was taken by Clementia Taylor and the audience heard for the first time women speak from a London platform in the furtherance of their cause. The following year on 26th March 1870, another meeting was held, this time in the Hanover Square Rooms, again with Taylor in the chair. Among the speakers were Katherine Hare, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Harriet Grote, Helen Taylor, John Stuart Mill and Charles Wentworth Dilke. (25)

Marriage

On 2 January 1872, at Hook, Surrey, Katherine Hare married the Revd Lewis Clayton (1838–1917), son of John Clayton, solicitor. Her husband became vicar of St Margaret's, Leicester, in 1875, and a canon of Peterborough in 1888, and was later suffragan bishop of Leicester (1903–13) and assistant bishop of Peterborough from 1912. They had three sons and one daughter, Katherine Emily Roberts (1877–1962), the hymn writer. (26)

After her marriage and the birth of her children, Katherine Clayton disappeared for some time from the suffrage movement. However, in 1896 she signed a memorial to Arthur Balfour, asking him to ensure that government time was allowed to discuss the Parliamentary Franchise (Extension to Women) Bill. (27)

Katherine Clayton was noted for her campaign to raise a memorial to Catherine of Aragon, the wife of Henry's VIII who was buried in Peterborough Cathedral. "The black marble slab in the cathedral, placed there in March 1895 to commemorate the queen, was funded by the unconventional means of inviting every Katherine in the country to contribute a penny to the cause". For fifteen years she was a member of the Peterborough board of poor law guardians, and she was secretary and president of the diocesan branch of the Mothers' Union. In 1927 she was made a freeman of Peterborough and in 1930 she was created OBE for services to education in Peterborough. (28)

Katherine Hare Clayton died at 18 Eccleston Square, London, on 10th November 1933.

Primary Sources

(1) Rosemary Mitchell, Marian Andrews : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (14th May 2020)

The third sister of Marian Andrews, Katharine Clayton [née Hare] (1843–1933), voluntary worker, was born at 1 Pelham, Place, Brompton, on 9 April 1843. Before her marriage, living at the family home, Gosbury Hill, Hook, she was a signatory to the women's suffrage petition of 1866 and became a member of the executive committee for the London National Society for Women's Suffrage in 1867; she also campaigned with Emily Davies to extend the local examination system to girls. On 2 January 1872, at Hook, Surrey, she married the Revd Lewis Clayton (1838–1917), son of John Clayton, solicitor. Her husband became vicar of St Margaret's, Leicester, in 1875, and a canon of Peterborough in 1888, and was later suffragan bishop of Leicester (1903–13) and assistant bishop of Peterborough from 1912. They had three sons and one daughter, Katharine Emily Roberts (1877–1962), the hymn writer.

(2) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000)

Thomas Hare (1806-91) was a political reformer... Both his daughters, Katherine Hare (1843-1933) and Alice Westlake (1842-1923), signed the 1866 women's suffrage petition. Katherine Hare in 1864 was interested in the movement led by Emily Davies to extend the Local Examination system to girls and was a member of the Kensington Society. She and her father were friendly with Philippine Kyllmann and entertained Lydia Becker at Gosbury Hall in July 1867. Katherine Hare was, from 1867, a member of the executive committee of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage and was one of the speakers, at Helen Taylor's behest, at the women's suffrage meeting, home to the public, held at the Hanover Square Rooms in March 1870.

(2) Helen Taylor, letter to Barbara Bodichon (9th May, 1866)

It seems to me that while a Reform Bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from different classes - asking for representation or protesting against disenfranchisement should say so, and that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so, and that women not saying so now will be used against them in the future and delay the time of their enfranchisement.... I think the most important thing is to make a demand and commence the first humble beginnings of an agitation for which reasons can be given that are in harmony with the political ideas of English people in general. No idea is so universally accepted and acceptable in England as that taxation and representation ought to go together, and people in general will be much more willing to listen to the assertion that single women and widows of property have been overlooked and left out from the privileges to which their property entitles them, than to the much more startling general proposition that sex is not a proper ground for distinction in political rights...

We should only be petitioning for the omission of the words male and men from the present act... If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up my father will gladly undertake to present it and will consider whether it might be made the occasion for anything further. He could at least move for a return of the number of householders disqualified on account of sex, which could be useful to us in many ways if it could be got. I shall be very glad to subscribe £20 towards expenses.