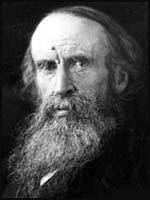

Leslie Stephen

Leslie Stephen was born at Hyde Park Gate, Kensington, on 28 November 1832. His father James Stephen (1789–1859), was under-secretary of the Colonial Office. His family were very religious and were members of the Clapham Sect. Leslie was a delicate child, and in 1840 his parents moved to Brighton in an attempt to improve his health.

Stephen was sent to Eton College in 1842. He also attended lectures by Frederick Denison Maurice at King's College before entering Trinity College in 1850. Among the friends he made as an undergraduate were Henry Fawcett, James Payn and Edward Dicey.

After graduating he was made deacon by the Archbishop of York on 21st December 1855. As his biographer pointed out: "He preached occasionally in the college chapel and at the town church of St Edward's, but soon found that his vocation lay more in teaching and in encouraging the young. He taught some mathematics, but his pastoral work lay mostly in the social life of the college, in friendship with and guidance of the undergraduate body, and not least in coaching and indeed vigorously participating in rowing and athletics."

Stephen was a keen mountaineer and according to his friend, Douglas Freshfield, later commented that "the Alps were for Stephen a playground but they were also a cathedral". He climbed the Eiger Joch (1859), the Schreckhorn (1861), Mont Blanc (1861), the Viescher Joch (1862) and Zinal Rothhorn (1864). He was also president of the Alpine Club (1865-68) and editor of the Alpine Journal.

Stephen began to lose his faith and he felt he was unable to take church services and was asked to resign his tutorship. However, he was offered other work at Trinity Hall. He later recalled: "I did not feel that the solid ground was giving way beneath my feet, but rather that I was being relieved of a cumbrous burden. I was not discovering that my creed was false, but that I had never really believed it". Leslie Stephen joined the Liberal Party and worked for Henry Fawcett in his attempts to enter the House of Commons. Stephen visited America in 1863, where he met Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Henry Longfellow.

In 1865 he left the University of Cambridge and attempted to become a full-time writer. A great supporter of the anti-slavery cause during the American Civil War he published The American War: a Historical Study (1865) and contributed articles to The Saturday Review, The Pall Mall Gazette, The Nation, The Cornhill Magazine, Fraser's Magazine and The Fortnightly Review.

Leslie Stephen married Harriet Thackeray, the daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray, on 19th June 1867. After a difficult pregnancy (there had earlier been a still birth) a daughter, Laura Makepeace Stephen, was born on 7th December 1870. The following year Stephen was appointed editor of The Cornhill Magazine on a salary of £500 a year. As editor he persuaded Thomas Hardy, Edmund Gosse, Henry James, John Addington Symonds and Charles Lever to write for the journal. In 1873 a collection of articles, taken from Fraser's Magazine and The Fortnightly Review, was published as Essays on Freethinking and Plainspeaking.

His first daughter, Laura had been slow to develop physically after her premature birth, and in childhood she increasingly revealed signs of mental problems. Harriet Stephen had another difficult pregnancy and on 28th November, 1875, she died of eclampsia. According to his biographer, Alan Bell: "Stephen threw himself compulsively and reclusively into work." His History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century (1876). It was well received and he now turned to his next project The Science of Ethics.

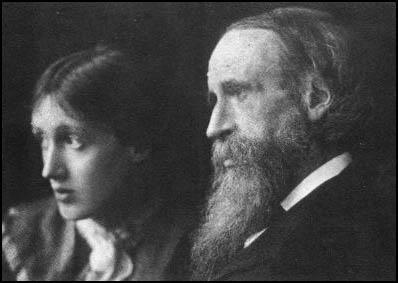

Leslie Stephen married the widow, Julia Princep Duckworth on 26th March 1878. She had three children from her first marriage, George Duckworth (1868–1934), Stella Duckworth (1869–1897), and Gerald Duckworth (1870–1937). Over the next few years she gave birth to four more children: Vanessa Stephen (1879), Thoby Stephen (1880), Virginia Stephen (1882) and Adrian Stephen (1883). Later, his first child, Laura, was placed in a home for "the imbecile and weak-minded" at Earlswood, and spent the rest of her life in a series of similar establishments.

Stephen published The Science of Ethics in 1882. He was very upset by the book's reviews, especially one by Henry Sidgwick, who argued that it did not come up to the expectations of professional philosophers. Stephen now began a series of short biographies, entitled, English Men of Letters. These were very popular and George Smith was inspired to pay Stephen a yearly salary of £800 to edit a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, The Dictionary of National Biography. The first volume was published in January 1885. Stephen's own contributions included Charlotte Brontë, Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Cowper, and Thomas de Quincey.

The The Dictionary of National Biography was not a financial success. In 1887 the dictionary was showing losses of £1000 each quarter, and the price had to be raised from 12s. 6d. to 15s. a volume. Stephen worked long hours on the project and told his sister: "When I'm not going at full speed, I drop". In the summer of 1889 he collapsed and he was told by his doctor that he had to slow down for the sake of his health. He eventually resigned as editor in April 1891. He wrote to his niece: "I felt melancholy at saying good-bye to the Dictionary. It cost me a slice of my life, but has been a good bit of work, though my share in it has diminished. I don't know whether to be glad or sorry that I took it up; but I part from it with a sense that I am being laid on the shelf."

Julia Stephen died suddenly on 5th May 1895, following an attack of influenza which had turned into rheumatic fever. His biographer, Alan Bell, has pointed out: "He almost immediately sought relief in literary work, easing the pain of his loss by preparing an intimate family memoir to preserve for her children a record of their courtship and marriage. Even in the depths of his sorrow he was methodical, working up documentary evidence from letters into a dated sequence around which he could build his own memories. The grief shows itself, as was intended, in many unbridled passages, but these gain from being grafted onto a well-crafted essay prepared by an experienced biographer."

In April 1897, his step-daughter, Stella Duckworth, married a solicitor, John Hills. Just over a fortnight later the bride suffered an attack of peritonitis, and following surgery she died, aged twenty-eight. This period was also blighted by arguments with his daughter, Vanessa Stephen, who resented the "dominion of a rapidly ageing and increasingly deaf father all too inclined to be brutally assertive over the details of household accounts." Stephen also held conventional views on education and unlike their two brothers, Vanessa and Virginia Stephen did not go to university.

According to Virginia's biographer, Lyndall Gordon: "Virginia's strongest memories from childhood were the idyll of St Ives, a basis for art, and at the other extreme, humiliation at the age of six when Gerald Duckworth, her grown-up half-brother (the younger son of her mother's first marriage), lifted her onto a ledge and explored her private parts - leaving her prey to sexual fear and initiating a lifelong resistance to certain forms of masculine authority." Virginia also complained about being bullied and sexually abused by another of her step-brother's George Duckworth.

In 1900 Leslie Stephen published the three-volume, The English Utilitarians, a three-volume work eventually published in 1900. He was aware of its defects and confessed to his friend, the historian, Frederic William Maitland, that "I could write a good slashing review of it".

In April 1902 Stephen discovered he was suffering from cancer. He was nursed by his two daughters, Vanessa Stephen and Virginia Stephen and died at his home at Hyde Park Gate on 22nd February 1904. His ashes were buried next to his second wife's grave, in Highgate Cemetery.