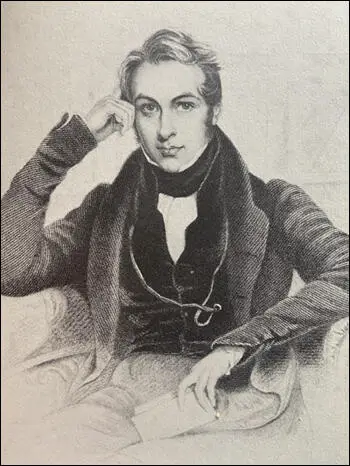

Frederick Denison Maurice

Frederick Denison Maurice was born at Normanton, near Lowestoft, on 29rd August 1805, the fifth child and only son of Michael Maurice and his wife, Priscilla Hurry Maurice, daughter of a Yarmouth merchant. In 1792 his father elected evening preacher at the Unitarian chapel in Hackney in London, where Joseph Priestley preached in the mornings. (1)

Maurice was educated by his father in Puritan principles. He studied the Bible and the History of the Puritans by Daniel Neal. He also attended meetings of the Anti-Slavery Society, the Bible Society, and similar institutions. Maurice was brought up to hero worship, Francis Burdett, Henry Brougham and Joseph Hume. (2)

Maurice's mother abandoned unitarianism in 1821. Maurice, who had been intended by his father for the ministry, had by this time also rejected this philosophy.To escape from the difficulties of his position he resolved to become a barrister. The son of Thomas Clarkson offered to take him as a legal pupil gratuitously. However, he decided to get a university education first and he entered Trinity College, in the October term of 1823. (3)

Maurice spoke at the Cambridge Union and was one of the founders of the well-known Apostles' Club, and formed a close intimacy with John Sterling. With Sterling he migrated in October 1825 to Trinity Hall, where the fellowships were tenable by barristers and given for a law degree. He went to London to read for the bar in the long vacation of 1826, and in the following term returned for the examination, and took a first-class in the ‘civil law classes' for 1826–7. (4)

Journalism

While at Cambridge he edited the Metropolitan Quarterly Magazine, which first appeared in November 1825, and lived through four numbers. He wrote several articles, attacking Jeremy Bentham while praising Lord Byron, William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Walter Scott and Robert Southey. He also expressed unqualified admiration for Samuel Taylor Coleridge, at this time his chief guide in philosophy. Maurice believed that Coleridge "felt that he had rescued Christianity from a shallow debate about its veracity according to severe rationalist principles and provided it with a much more substantial philosophical grounding that was more realistically related to human experience." (5)

Frederick Denison Maurice contributed to the Westminster Review in 1827 and 1828, and joined the debating society of which John Stuart Mill was a member. (6) Maurice decided he wanted to be a journalist but was handicapped by his difficulty making friends. He wrote to his father about his problems making close friends: "I have felt a painful inability to converse even with those who loved me upon the workings of my mind." Brenda Colloms has argued that "Nobody doubted that young Maurice had great potential and most persons assumed that he was poised on the threshold of a dazzling career... He was deeply depressed and frustrated, having found that journalism was just as confining as any other profession. An unforeseen problem, for Maurice at least, was that a successful journalist needed to possess the knack of making friends." (7)

Church of England

In 1828 Maurice was appointed editor of the highly regarded journal, Athenaeum, where he advocated social reform. However, the job was not well-paid and he decided to move back to his family home. His father had lost money through unsound investments and was no longer able to take in pupils. The family moved to Southampton and to a smaller house, where Frederick Maurice joined them. In the meantime his religious beliefs had undergone change; the Unitarianism of his upbringing was rejected and he resolved on ordination in the Church of England. Preparation for this meant a return to university life, and entered Exeter College in 1830. (8)

Maurice was ordained in January, 1834 and became a curate at Bubbenhall, near Leamington. Two years later he was offered two part-time jobs, chaplain to Guy's Hospital and Professor of Divinity at King's College. The combined salaries were sufficient to live upon, Maurice accepted the two positions, and with his sister Priscilla accompanying him as housekeeper, he moved to London. Maurice visited patients in the wards as well as preaching in the hospital. For the first-time in his life he became aware of the problems of working-class people. (9)

In June 1837 Maurice visited his old university friend, John Sterling, and met Anna Barton, sister of Sterling's wife. He immediately fell in love with Anna. He felt, he said later, like a man who had travelled all his life under oppressive cloudy skies and suddenly came into perpetual sunshine. Anna shared the same feelings and they became engaged and they were married by Sterling at Clifton on 7th October 1837. (10)

After their marriage Anna helped her husband with his work. She took down dictation from her husband for his articles and lectures and translated German articles for him. Anna helped him to collect some letters he had written to a Quaker acquaintance. This formed the basis of the book, The Kingdom of Christ (1838). In the book Maurice argued that politics and religion are inseparable and that the church should be involved in addressing social questions. Maurice rejected individualism, with its competition and selfishness, and suggested a socialist alternative to the economic principles of laissez faire. He suggested profit sharing as a way of improving the status of the working classes and as a means of producing a just, Christian society. According to his biographer, Leslie Stephen: "The publication was the signal for the beginning of a series of attacks from the religious press, which lasted for the rest of his life, and caused great pain to a man of a singularly sensitive nature. The book contains a very full statement of his fundamental convictions, which were opposed to the tenets of all the chief parties in the church." (11)

In September 1839 Maurice assumed part editorship of a new periodical, the Educational Magazine, his concern for national education having been heightened by the growing social unrest of the time caused by the demands for parliamentary reform. The following year he became sole editor, continuing to press the argument that the responsibility for schools should remain within the control of the Church of England, through agreement by the government with the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor. (12)

In June 1840 Maurice was elected to a professorship in English literature and history at King's College. During this period he began to be influenced by the ideas of people like Thomas Carlyle, Benjamin Disraeli and John Ruskin who believed that a better society would be achieved by beneficent gestures from the leaders of the led. However, they also thought that there was a sharp distinction between the "masters and the rest" and that "without a master the ordinary man does not work". (13)

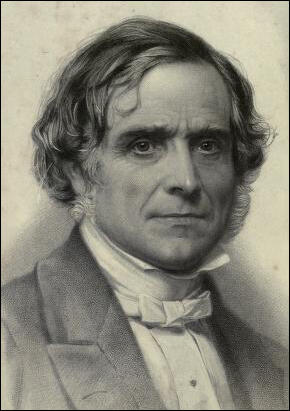

Anna Maurice gave birth to two sons (Frederick and Charles) but she developed tuberculosis and the disease. Maurice wrote in December 1844 that they hoped she would recover because only one lung was affected, but he was mistaken. Her condition deteriorated and next spring she was taken to Hastings for the sea air. He told a friend that: "When I look on her withered face and limbs I can scarcely dream that this measure will be blessed by her recovery." Anna died on 18th April 1845 and was buried at Herstmonceux. His sister, Priscilla, moved in with him to look after the two boys. (14)

In 1845 Maurice began receiving letters from Charles Kingsley, the rector of Eversley Church. This started a correspondence on parish and theological matters, and came increasingly under his influence. In 1847 Maurice became godfather to the Kingsleys' second child, a son who was named after him. Another friend, John Ludlow, said: "Mr Maurice's affection for him was unspeakable. I have often doubted whether he really ever loved anyone except Kingsley of all the young men who began to gather round him." (15)

In 1846 he and other members of the staff at King's founded Queen's College in Harley Street. for the higher education of women, particularly of intending governesses, in whose needs his sister Mary, herself a teacher, was interested. Maurice announced that the object of the college was to teach "all branches of female knowledge". This created some controversy as some men thought it was "dangerous" to teach women Mathematics. Maurice replied: "We are aware that our pupils are not likely to advance far in Mathematics, but we believe that if they learn really what they do learn, they will not have got what is dangerous but what is safe." (16)

From the beginning the classes were open to all girls and women above the age of twelve. The college was divided into seniors and juniors, and soon it became necessary to open a preparatory class for younger girls and to offer additional classes in the evening. Fees were charged for each subject according to the number of weekly classes held in it. Education was by a system of lectures and essays. Maurice discouraged competition and allowed neither rewards nor punishments. (17) Charles Kingsley was appointment as professor of English and gave lectures on Anglo-Saxon literature and history. (18)

The first group of students to attend this new training school for teachers included Adelaide Anne Procter, Dorothea Beale, Sophia Jex-Blake and Francis Mary Buss. The feminist historian, Rachael Strachey, has criticised Queen's College because its constitution, was entirely governed by men. However, some important figures that took part in campaign for women's suffrage, received their education from this institution: "They gave encouragement to their secret and half-realised dreams, and Maurice, Kingsley, and their friends, by sanctioning and encouraging these girls, rendered an immense service to the Women's Movement." (19)

Christian Socialism

Frederick Denison Maurice supported what became known as Moral Force Chartism: The group drew up a list of six political demands. "(i) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime. (ii) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (iii) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (iv) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (v) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (vi) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period." (20)

On 10th April, 1848, a group of Christians who supported Chartism held a meeting in London. People who attended the meeting included Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley, John Ludlow and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class. (21)

Feargus O'Connor had been vicious attacks on other Chartist leaders such as William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, Bronterre O'Brien and Henry Vincent who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor became the leader of what became known as the Physical Force Chartists, Disturbed by these events members of the Christian Socialist movement volunteered to become special constables at these demonstrations. (22) John Ludlow later wrote: "The present generation has no idea of the terrorism which was at that time exercised by the Chartists." (23)

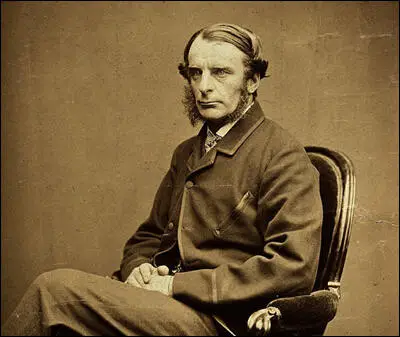

John Ludlow, a lawyer who had been deeply influenced by the socialist writer, Henri de Saint-Simon, was another important figure in the group. He sought to Christianize Socialism as he believed structural change was needed and charity was not enough. He had been a social worker in London and had commented: "It seemed to me that no serious effort was made to help a person out of his or her misery, but only to help him or her in it." (24) Ludlow also brought his colleague Frederick James Furnivall into the group. (25)

In April 1849, Charles Kingsley wrote to his wife about the plan to publish a political newspaper. "I really cannot go home this afternoon. I have spent it with Archdeacon Hare, and Parker, starting a new periodical, a Penny People's Friend, in which Maurice, Hare, Ludlow, Mansfield, and I are going to set to work to supply the place of the defunct Saturday Magazine. I send you my first placard. Maurice is delighted with it. I cannot tell you the interest which it has excited with everyone who has seen it.... I have got already £2.10.0 towards bringing out more, and Maurice is subscription hunting for me." (26)

The following month Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley, Thomas Hughes, Charles Blachford Mansfield and John Ludlow began publishing a penny journal, Politics for the People, and this was considered the starting-point of the Christian Socialist movement. It was "sympathetic to the poor and based upon the acknowledgment that God rules in human society... They addressed themselves to workmen. They confessed that they were not workmen, but asked for workmen's help in bridging the gulf that divided them". (27)

The journal was selling at about 2,000 copies an edition. (28) Charles Kingsley wrote several articles for the journal. He took the signature ‘Parson Lot,' on account of a discussion with his friends, in which, being in a minority of one, he had said that he felt like Lot, "when he seemed as one that mocked to his sons-in-law." (29) Charles Blachford Mansfield adopted the pseudonym Will Willow-wren. Mansfield agreed with other members of the group that the essays were designed to help the working man escape from "dull bricks and mortar and the ugly colourless things which fill the workshop and the factory." (30)

Charles Kingsley made it clear he was a supporter of Chartism: "My only quarrel with the Charter is, that it does not go far enough... Instead of being a book to keep the poor in order, it (the Bible) is a book, from beginning to end, written to keep the rich in order. It is our fault. We have used the Bible as if it was a mere special constable's handbook - an opium-dose for keeping beasts of burden patient while they were being over-loaded." (31)

Charles Blachford Mansfield's theology was based more on a rationalist concept of a Divine Idea than on a clear Christian faith. When his father heard of his involvement in the Christian Socialist movement he immediately cut his allowance, and Mansfield adopted the vegetarian diet and simple lifestyle for which he became renowned. However, it had a serious impact on his ability to finance the group's publishing ventures. (32)

During the summer of 1848, Charles Blachford Mansfield, Charles Kingsley, Thomas Hughes and John Ludlow would have editorial meetings at the house of Frederick Denison Maurice. Important socialists of the day, including Robert Owen, the owner of the New Lanark Mills and Thomas Cooper, one of the leaders of the Chartist movement, sometimes took part in these discussions. (33)

Politics for the People was an expensive journal to produce and by July 1848, after seventeen editions, the decision was taken to stop publication. However, the group continued to meet, generally in Ludlow's chambers, and a result of their discussions was the foundation of a night school in Little Ormond Yard. (34)

The group continued to meet on a regular basis. New members included Lloyd Jones, who had opened a Cooperative store in Salford in 1831. Leaders of the Chartist movement, including Feargus O'Connor and Bronterre O'Brien attended meetings. The Scottish tailor Walter Cooper, introduced two watchcase finishers, Joseph Millbank and Thomas Shorter, to the group. (35)

Even liberal newspapers became concerned by the Christian Socialists support for the trade union movement and the idea of cooperation rather than capitalism. The Daily News argued: " to erect on their unfortunate workshops of Christian Socialism, as Mr Maurice, of King's College, in the Strand, is pleased to term his hostility to the principle of commercial competition, about which he seems to know as much as it is to be presumed he does of single stitch. Already there are attempts to connect the working tailors' case with the teaching of the Communist doctrine." (36)

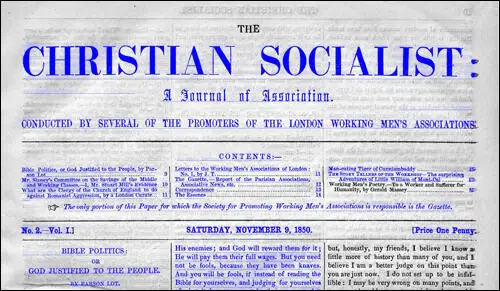

On 2nd November, 1850, the group launched a new journal, Christian Socialist. "On its first page it stated what it was trying to do: "A new idea has gone abroad into the world. That is Socialism, the latest-born of the forces now at work in modern society, and Christianity, the eldest born of those forces, are in their nature not hostile, but akin to each other, or rather that the one is but the development, the outgrowth, the manifestation of the other, so that even the strangest and most monstrous forms of Socialism are at bottom but Christian heresies. That Christianity, however feeble and torpid it may seem to many just now, is truly but as an eagle at moult, shedding its worn-out plumage; that Socialism is but the livery of the nineteenth century (as Protestantism was its livery of the sixteenth) which is now putting on, to spread long its mighty wings for a broader and heavenlier flight. That Socialism without Christianity, on the one hand, is as lifeless as the feathers without the bird, however skillfully the stuffer may dress them up into an artificial semblance of life; and that therefore every socialist system which has endeavoured to stand alone has hitherto in practice either blown up or dissolved away; whilst almost every socialist system which has maintained itself for anytime has endeavoured to stand, or unconsciously to itself has stood, upon those moral grounds of righteous, self-sacrifice, mutual affection, common brotherhood, which Christianity vindicates to itself for an everlasting heritage." (37)

John Ludlow was the editor of this new venture. It was to be a rule of the journal that writers should be anonymous, a common practice of the time. Ludlow's pen-name was John Townsend, or J.T. It was announced in the first edition that the journal would cover the entire spectrum of English life: free trade, education, the land question, poor laws, reform of the law, sanitary reform, taxation, finance, and Church reform. (38)

John Ludlow pointed out in his first editorial: "We do not mean to eschew Politics.We shall have Chartists writing for us, and Conservatives, and yet we hope not to quarrel, having this one common ground of Socialism, just as on the ground we hope not to quarrel, though the professing Christian be mixed in our ranks with those who have hitherto passed for Infidels." (39)

The journal was remarkable value at a penny a copy, for it was about 16,000 words of closely packed material with no paid advertising. It sold around 1,500 copies a week, in spite of its difficulties in finding any distributors to handle it. Brenda Colloms has argued: "Anyone who bought the first copy, and continued to buy it each week would find he had embarked upon an adult education course of a highly specialized nature." (40)

Chartists had been suspicious of Politics for the People and had not read it for that reason, decided that perhaps they should give this middle-class group a chance, and they began to read the Christian Socialist. Many found it to their liking and wrote articles for it. This included Gerald Massey, a genuine people's poet. Massey, the son of a canal boatman, was born in a hut at Gamble Wharf, on 29 May 1828. His father brought up a large family on a weekly wage of some ten shillings. Massey said of himself that he "had no childhood." After a scanty education at the national school at Tring, Massey was when eight years of age put to work at a silk mill. (41)

By 1850 Gerald Massey had moved to London and was working as a freelance journalist. John Ludlow was disturbed that Massey was a follower of George Julian Harney and was a regular contributor to the Red Republican. Ludlow was eager to have Massey write for his paper but made it clear that he had to stop writing for those publications that supported Physical Force Chartism. According to Brenda Colloms: "Massey did not object, for like so many working-class men reared on Nonconformist religious books and ideas, he found the ideas of brotherhood in associations more emotionally satisfying than the cooler and more impersonal socialist dogma." (42)

Another working class agitator who contributed to the Christian Socialist was John James Bezer. He in the past had been one of the leaders of the Chartist movement calling for revolution. On the 26 July 1848 Bezer attended a meeting chaired by John Shaw of the City Lecture Theatre, Milton Street, Cripplegate, where the subject was "Of bringing before the Legislature and the Public the despotic treatment of the Chartist victims." A strong force of police was standing by in case of disturbance. Two days later, at the same venue, Bezer conducted a public meeting condemning the Government's handling of the current problems in Ireland. It was reported that some 1,000 persons mostly Irish were in attendance both inside and outside the hall. Also present were the police and reporters who took notes of what men said at the meeting. (43) Several men at the meeting, including Bezer, Robert Crowe (tailor), George Shell (shoemaker) and John Maxwell Bryson (dentist) were arrested and charged with sedition. (44)

In court it was claimed that Bezer had called on Chartists "to destroy the power of the Queen, and establish a Republic." Bezer was accused of telling people that he would be able to supply 50 fighting men, and that they "were going to get up a bloody revolution". Bezer, Shell, Bryson and Crowe were all found guilty of sedition. According to The Leicestershire Mercury "The jury returned a verdict of guilty; and the other defendants who had been convicted to receive sentence. Mr Baron Platt in passing sentence, addressed them at some length upon their conduct, and told them as the sentence passed upon them at a previous session did not appear to have deterred them, it was clear an increase of severity of punishment must be resorted to: He then sentenced George Smelt, Robert Crowe, and John James Bezer to be imprisoned in the house of correction for two years, to pay a fine of £10 each to the Queen, and at the expiration of their imprisonment to enter into their own recognizances in £100 with two securities of £50 each, to keep the peace for five years." (45)

John James Bezer met John Ludlow and agreed to contribute to the The Christian Socialist. Ten chapters of Bezer's autobiography were published as installments in the journal from 9 August 1851. David Shaw has argued that the autobiography "considering the circumstances, surprisingly well written - record forms both an interesting and an important portrayal, at first hand, of working-class life in Dickensian London." (46)

Soon afterwards John James Bezer met John Bedford Leno at a Christian Socialist meeting. Leno agreed with Bezer that violence between the Chartists and the police was inevitable, and that arms should be carried. Leno later wrote in his autobiography: "In truth, I was for rebellion and civil war, and despaired of ever obtaining justice, or what I then conceived it to be, save by revolution." (47) Leno, who had been apprentice in the printing trade and it was agreed that they should a printers's cooperative, and The Christian Socialist journal became its main customer. (48)

George Julian Harney, a great supporter of John James Bezer, was disgusted by this development. Harney had used his newspaper, The Red Republican to promote Physical Force Chartism. With the help of his friend, Ernest Jones, Harney attempted to use his paper to educate his working class readers about socialism and internationalism. Harney also attempted to convert the trade union movement to socialism. Harney knew that the The Christian Socialist movement was totally opposed to the use of violence and feared that Bezer had "gone over to the enemy". (49)

The journal had a dual purpose. It was a vehicle of Christian Socialist propaganda on the one hand and a "Journal of Association", giving news of current associations and instructions on how to form new ones, on the other. The Christian Socialist became the official mouthpiece of the Christian Socialist movement and resulted in conflict between Frederick Denison Maurice and John Ludlow the editor. Maurice was critical of some of the articles that called for universal suffrage. Ludlow also refused to publish an article by Charles Kingsley on the Bible story of the Canaanites for its incipient racism. (50)

Joseph Millbank and Thomas Shorter, joint secretaries of the Society of Promoters, argued the cooperation was needed to combat poverty in Britain. "We have become rivals where we ought to have become brethren, and have competed with each other when we ought to have cooperated - rivals, with more or less of hate, and hosts of expedients to disguise its hideousness and make it respectable." (51)

The editorship of the The Christian Socialist dominated the life of John Ludlow and he was devastated when it had to stop publication on 28th June 1851 because it was losing too much money. Ludlow and other Christian Socialists now concentrated on publishing pamphlets. However, this caused conflict amongst the leaders. In 1852 Frederick Denison Maurice concluded that the "idea of Christian Socialism were so divergent that only confusion was created when they spoke up." Ludlow agreed and said that different members "had meant different things by the words they used." (52)

The Cooperative Movement

Maurice's biographer, Bernard Reardon, has argued: "He (Maurice) disliked competition as fundamentally unchristian, and wished to see it, at the social level, replaced by co-operation, as expressive of Christian brotherhood... Maurice held Bible classes and addressed meetings attended by working men who, although his words carried less of social and political guidance than moral edification, were invariably impressed by the speaker. But the actual means by which the competitiveness of the prevailing economic system was to be mitigated was judged to be the creation of co-operative societies." (53)

Maurice and the Christian Socialists discussed the idea of establishing cooperative workshops. An early suggestion was one involving the clothing industry. One member of the group, Charles Kingsley, had been interested in the subject for sometime and at that time he was working on a pamphlet, Cheap Clothes and Nasty and a novel, Alton Locke with the objective of exposing the sweatshop system. (54)

At a meeting of about twenty people at the home of Frederick Denison Maurice it was decided to form the Cooperative Association of Working Tailors, that, they hoped, would end capitalist owners' exploitation. It was founded on a resolution which stated that "individual selfishness, as embodied in the competitive system, lies at the root of the evils under which English industry now suffers: the remedy for the evils of competition lies in the brotherly and Christian principle of Co-operation, that is, of joint work, with shared or common profits." (55)

Walter Cooper was chosen as manager and a committee was elected to raise money for rent, purchase of material and cash in hand for wages, a sum of £350. Operating rules were formulated and a three-year lease was signed on the 18th January on a spacious building at 34 East Castle Street, just off Oxford Street. Another political radical, Gerald Massey, was employed as the company's bookkeeper (56)

Robert Crowe, a Christian Socialist and tailor, was in prison for taking place in a Chartist demonstration when was released from prison in the summer of 1850. "On Monday morning, at 6 am nearly 2,000 persons assembled at the gate to greet me as I crossed the threshold." (57) The Christian Socialist movement had been monitoring the situation and was keen to set up a series of cooperatives. Charles Kingsley, Crowe's old friend, had commented: "Competition is put forth as the law of the universe. That is a lie. The time has come for us to declare that it is a lie by word and deed. I see no way but associating for work instead of for strikes." (58)

Crowe later explained that: "A few days later (after my release from prison) I received an invitation from the manager of the Tailors' Cooperative Association, Walter Cooper, offering me the privilege of work. I accepted and have commenced my acquaintance with the young and gifted poet, Gerald Massey, whose Lyrics of Freedom have become favourites with all liberal minds throughout the Kingdom. He was the bookkeeper to the association. (59)

Workrooms on the top floor, with offices and a shop on the lower floors were fitted out, and the building opened for business with twelve employees on 11th February 1850. Wages for the workers soon compared favourably with those of other trades, averaging 24s per week. That month, Frederick Denison Maurice published the first of a series of eight Tracts on Christian Socialism in which he presented, so he thought, his own clear convictions on the subject. "In general, Christian Socialism was taken to mean a restructuring of labour based on co-operation, joint ownership and with increased power to the working class." (60)

The promoters of the Christian Socialists with their high clerical connections received visits from many upper class persons of distinction who were desirous of seeing at first hand the practical work being achieved by the associations. This included Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford, for a new set of liveries. (61) It is claimed that the Bishop told Cooper: "Well, now, Mr Cooper, this is really delightful, to see a number of men while engaged at their work singing praises to the glory of God. I am delighted at this spectacle!" (62)

In 1851 Edward Vansittart Neale and Thomas Hughes, without the direct sanction of the Christian Socialist Council, they established the Central Co-operative Agency, which anticipated the Co-operative Wholesale Society. Some of the members strongly disapproved of this experiment. The publication of an address to the trade societies of London and the United Kingdom, inviting them to support the agency as "a legal and financial institution for aiding the formation of stores and associations, for buying and selling on their behalf, and ultimately for organising credit and exchange between them" brought matters to a crisis, and an attempt was made to exclude Neale and Hughes from the council. (63)

An important figure in the cooperative movement was Edward Vansittart Neale whose wealth helped to subsidize the Tailors' Cooperative Association. Progress was swift in the establishment of other working associations. By the time of the first annual conference of the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations in the summer of 1852 there were twelve associations up and running, covering tailors, builders, shoemakers, pianomakers, printers and bakers. (64)

Thomas Hughes was a passionate supporter of the cooperative movement and later wrote: "We were all full of enthusiasm and hope in our work, and of propagandist zeal: anxious to bring in all the recruits we could. I cannot even now think of my own state of mind at the time without wonder and amusement. I certainly thought (and for that matter have never altered my opinion to this day) that here we had found the solution of the great labour question; but I was also convinced that we had nothing to do but just to announce it, and found an association or two, in order to convert all England, and usher in the millennium at once, so plain did the whole thing seem to me." (65)

Leading figures in the Christian Socialist movement toured the country advocating cooperative workshops. This included Lloyd Jones, who was "one of the keenest and most eloquent of cooperators, was put in charge as a missionary for the agency, and for cooperation in the North generally." Also heavily involved was John Ludlow who organised a cooperative conference in Bury on 18th April 1851. He argued that "the idea of a provincial wholesale depot is in the minds of all the Lancashire cooperatives; that the plan for its establishment is already drawn up... and that the only question respecting it is whether it shall be set up in Manchester or Rochdale." (66)

Walter Cooper was in great demand as a national speaker on the subjects of Christian Socialism, Worker's Cooperatives and Chartism. Some people claimed that Cooper was not spending enough time at Cooperative Association of Working Tailors and an investigation of the books suggested there were sixty false items in the accounts. Brenda Colloms claimed "that only four items could be said to be wrong, and those seemed to be the result of inexperience and sloppiness, so that any insinuation of fraud were baseless." (67) However, Chris Bryant, the author of Possible Dreams: A Personal History of the British Christian Socialist (1996) argues that "Walter Cooper turned out to be a weak manager and absconded with some of the Castle Street funds." (68)

The Tailors' Cooperative Association came to an end in about May 1852. One observer argued that the "association crumbled... owing to those internal causes which no success can prevent". However, Thomas Hughes, gave another reason when discussing his brother's involvement in the venture: "He continued to pay his subscription, and to get his clothes at our tailors' association till it failed, which was more than some of our number did, for the cut was so bad as to put the sternest principles to a severe test. But I could see that this was done out of kindness to me, and not from sympathy with what we were doing." (69)

The Christian Socialists also gave support to Caroline Southwood Hill and her daughters, including Octavia Hill, in the forming the Ladies' Cooperative Guild, a co-operative craft workshop for girls. Its aim was to give training to disadvantaged girls and young women in the making of ornamental glass and toy furniture. Based at 4 Russell Place, Bloomsbury, it was an early important initiative supporting the drive to increase women's employment opportunities. Southwood was appointed manager and book-keeper. (70)

Southwood Hill, published an article about the venture in Household Words, a magazine owned by Charles Dickens. "There is a large, light, lofty workshop, situated in one of the best thoroughfares of the town, in which are occupied about two dozen girls between the ages of eight and seventeen. They make choice furniture for dolls houses. They work in groups, each group having its own department of the little trade... A young lady whose age is not so great as that of the majority of the workers - only whose education has been infinitely better - rules over the little band; apportions the work; distributes the material; keeps the accounts; stops the disputes; stimulates the intellect, and directs the recreation of all." She compares her power to the Tsar of Russia "but the two potentates differ in this, that the one governs by fear, the other by affection." (71)

Frederick Denison Maurice offered to take a Bible class for the children working in the toy factory. The prospect of Maurice coming to the Ladies' Cooperative Guild horrified the evangelical ladies who supported it, and who sent to it the toymaker children from the Ragged School Union. They threatened to withdraw all support if Maurice gave his Bible class. Caroline Southwood Hill protested, and she was dismissed in late 1855. The Guild did not last long after her departure, although the toymaking carried on for a few more months. (72)

Edward Vansittart Neale continued to be a passionate supporter of the cooperative movement and in the early 1850s he put over £60,000 into launching twelve co-operative workshops for various trades. Neale prophesied that "an incalculable amount of good of every sort will arise... The great thing to impress upon the minds of the workers is the importance of seeking to raise the position of their class instead of limiting their efforts to raising their own position as individuals." (73)

Working Men's College

In May 1848 Frederick Denison Maurice, John Ludlow, and Charles Kingsley decided to publish a penny journal, Politics for the People, and this was considered the starting-point of the Christian Socialist movement. It was "sympathetic to the poor and based upon the acknowledgment that God rules in human society... They addressed themselves to workmen. They confessed that they were not workmen, but asked for workmen's help in bridging the gulf that divided them". (58) The paper only lasted till July, but the group continued to meet, generally in Ludlow's chambers, and a result of their discussions was the foundation of a night school in Little Ormond Yard. (74)

In 1852 Charles Blachford Mansfield argued that a Working Men's College was a natural development from the night classes in Little Ormond Yard. However, Mansfield failed to follow upon the idea. However, that winter several members of the group did provide lectures on a variety of different subjects. This included Maurice on William Shakespeare, Walter Cooper on the genius of Robert Burns, George Frederick Robinson on entomology, John Pyke Hullah on how to start a singing class, Richard Chenevix Trench on Proverbs, and Frank Cranmer Penrose on architecture. (75)

Frederick Denison Maurice had always been more interested in education than economics and was especially interested in establishing a Working Men's College. Radical speeches by other Christian Socialists also caused problems from his employers. After one speech by Charles Kingsley, on 22nd June 1851, The principal of King's College wrote to him hoping that he would disown Kingsley's utterances, which he deplored as "reckless and dangerous". Although he did not agree completely with Kingsley he refused to criticise his old friend. (76)

The publication of Maurice's Theological Essays in 1853 provoked even more controversy. Richard William Jelf, the Principal of King's College, was concerned that Maurice was being attacked by almost every section of the religious establishment because of his outspoken social views. Jelf also objected to him being associated with George Holyoake, the main promoter of Secularism. Jelf asked Maurice to resign. He refused and demanded that he be either "acquitted or dismissed." He was dismissed. (77)

On the news of his dismissal, over a thousand working-men, representing around a hundred occupations, published a letter of support for Maurice. "That you may long continue to pursue your useful and honourable career: that the eminent services you have confessedly rendered to the Church and to the cause of education, may meet with a more generous and grateful appreciation; that those who at present misunderstand and misrepresent you may learn by your example and that they may at least emulate you in the wisdom and zeal with which you had advocated the cause of the working-man, is the sincere and earnest desire of those whose names are hereunto appended." (78)

On reading the statement Maurice decided he would now put all his efforts into the formation of a Working Men's College. On 10th January, 1854, Maurice wrote to Charles Kingsley that he hoped that "my college" would soon be established. (79) The following day a meeting was held in Maurice's house that was attended by Thomas Hughes, Lloyd Jones and Edward Vansittart Neale, where it was agreed that the Promoters' Committee of Teaching and Publication be empowered to frame, and if possible carry out a plan to set up a People's College in London. (80)

Frederick Denison Maurice then drew up more concrete plans for a people's college that was to be founded in the premises of one of the failed associations at 31 Red Lion Square. In June and July a series of fund-raising lectures was given, and the college was ready for business in time for October, with a wide range of subjects and an interesting set of lecturers. The college was to be aimed specifically at the manual workers, and Maurice agreed to be Principle of the Working Men's College. (81)

It opened on 31st October 1854, with some 176 students. The most popular classes were Languages, English Grammar, Mathematics, Drawing whereas History, Law, Politics and the Physical Sciences attracted smaller attendance. Later the Working Men's College moved, first to Great Ormond Street and then to Crowndale Road. (82)

Frederick Denison Maurice was the Principal of the Working Men's College. Some of the teachers at the college included Edward Vansittart Neale, John Ludlow, Thomas Hughes, Lloyd Jones, John Ruskin, Frederick James Furnival, Charles Blachford Mansfield, Lowes Cato Dickinson and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Founder member of the Christian Socialists, Charles Kingsley, never taught at the college but popularized it whenever he could. (83)

Last Years

Maurice became increasingly conservative as he became older. Whereas some of his fellow Christian Socialists like John Ludlow were committed socialists, Maurice did not share these views. Maurice was not in favour of universal suffrage, and certainly no egalitarian: hierarchy he thought essential to society. As he told Ludlow: "Let people call me merely a philosopher, or merely anything else… my business, because I am a theologian, and have no vocation except for theology, is not to build, but to dig, to show that economics and politics… must have a ground beneath themselves, and that society was not to be made by any arrangements of ours, but is to be regenerated by finding the law and ground of its order and harmony, the only secret of its existence, in God." (84)

Maurice was still considered to be a radical thinker. Lucy Cavendish wrote in February, 1865: "We went to hear the famous Mr Maurice in the morning. He preached most beautifully on Triumphant Hope; with a manner full of love and fervour. If one had not known of his startling, peculiar opinions, I think one would have seen nothing in his sermon but what any Christian might agree with. But alas! There is terrible difficulty and dispute all round one now, and one is unconsciously on one's guard and in a state of distrust." (85)

In October 1866 Maurice became Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. However, he continued to run the Working Men's College in London, though he attended there less often. While at Cambridge Maurice wrote two influential books, Social Morality (1869) and Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy (1871). His health, however, was visibly declining. Even so, he did not refuse the bishop of London's offer of the Cambridge preachership at Whitehall, delivering sermons there in the winter months of 1871–2, as well as two university sermons in Cambridge. (86)

Frederick Denison Maurice died at 6 Bolton Row, Piccadilly, on 1st April 1872. Lucy Cavendish wrote in her diary: "The famous Mr Maurice is just dead; the papers for the most part speak on him with great respect, and indeed I believe he was a true Saint, though perhaps with the misfortune, which seems to belong to some schools of thought, of inspiring his disciples with his errors than his truths." (87)

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Denison Maurice, speech at the opening of Queen's College (1848)

The vocation of a teacher is an awful one… she will do others unspeakable harm if she is not aware of its usefulness… How can you give a woman self-respect, how can you win for her the respect of others… Watch closely the first utterances of infancy, the first dawnings of intelligence; how thoughts spring into acts, how acts pass into habits. The study is not worth much if it is not busy about the roots of things.

(2) James Martineau, Essays, Reviews, and Addresses (1890)

We venture with some confidence to assert, that for consistency and completeness of thought, and precision in the use of language, it would be difficult to find his (Maurice's) superior among living theologians.

(3) Benjamin Jowett, The Life and Letters of Benjamin Jowett (1897)

He (Maurice) was misty and confused, and none of his writings appear to me worth reading. But he was a great man and a disinterested nature, and he always stood by any one who appeared to be oppressed.

(4) Lucy Cavendish, diary entry (February 1865)

We went to hear the famous Mr Maurice in the morning. He preached most beautifully on Triumphant Hope; with a manner full of love and fervour. If one had not known of his startling, peculiar opinions, I think one would have seen nothing in his sermon but what any Christian might agree with. But alas! There is terrible difficulty and dispute all round one now, and one is unconsciously on one's guard and in a state of distrust.

(5) Alec R. Vidler, F. D. Maurice and Company (1966)

The impression that Maurice was the leader of "a school of thought' was natural and widespread, but no one who knew him intimately or who really understood him would have let it pass. For Maurice abhorred the very idea of leading a school of thought, of forming a party, or of gathering a body of disciples. But hardly any one of them at the time understand him. His friends and admirers were often as much mystified by him as his critics and opponents, though in a different way.

(6) Lucy Cavendish, diary entry (April 1872)

The famous Mr Maurice is just dead; the papers for the most part speak on him with great respect, and indeed I believe he was a true Saint, though perhaps with the misfortune, which seems to belong to some schools of thought, of inspiring his disciples with his errors than his truths.