Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

John Everett Millais became friends with William Holman Hunt, a fellow student at the Royal Academy School. They both rejected the ideas of Joshua Reynolds, who argued in his famous Seven Discourses on Art, that young British artists should follow in the Renaissance tradition, to admire the work of Raphael, and to aspire to the classical ideal "that perfect beauty never found in nature but attainable by the artist through careful selection and improvement". Hunt and Millais reacted against this view and in September 1848 they joined up with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Thomas Woolner and James Collinson to establish what became known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Other artists such as Charles Allston Collins and Ford Madox Brown were closely associated with the group but were never official members of the PRB.

The Pre-Raphaelites focused on serious and significant subjects and were best known for painting subjects from modern life and literature often using historical costumes. They painted directly from nature itself, as truthfully as possible and with incredible attention to detail. They were inspired by the advice of John Ruskin, the English critic and author of Modern Painters (1843). He had encouraged artists to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing."

John Everett Millais, who had already developed a reputation as a artist, now tried to put Pre-Raphaelite ideas into practice. His first major painting in the new style was Isabella. According to Malcolm J. Warner: "It shows the use of portraiture as an antidote to idealization, the stiffness of pose intended to recall medieval art, the minute, all-over detail, and the high colour key that characterized early Pre-Raphaelitism."

As Ian Chilvers, the author of Art and Artists (1990) has pointed out: "They (Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) chose religious or other morally uplifting themes and had a desire for fidelity to nature that they expressed through detailed observation of flora, etc., and the use of a clear, bright, sharp-focus technique... When their meaning became known in 1850 the group was subjected to violent criticism and abuse."

The most important attack on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood came from Charles Dickens in his journal Household Words on 15th June, 1850: "You will have the goodness to discharge from your minds all Post-Raphael ideas, all religious aspirations, all elevating thoughts, all tender, awful, sorrowful, ennobling, sacred, graceful, or beautiful associations, and to prepare yourselves, as befits such a subject Pre-Raphaelly considered for the lowest depths of what is mean, odious, repulsive, and revolting."

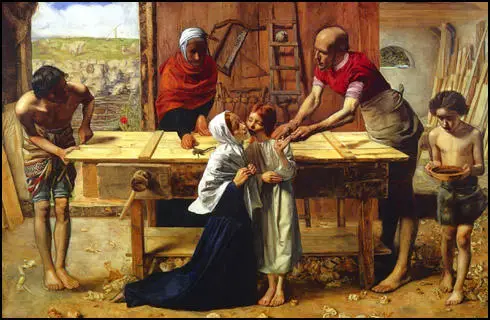

Dickens then went on to criticize Millias's painting, Christ in the House of His Parents, that had appeared for the first time at the 1850 Royal Academy Exhibition: "You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England. Two almost naked carpenters, master and journeyman, worthy companions of this agreeable female, are working at their trade; a boy, with some small flavor of humanity in him, is entering with a vessel of water; and nobody is paying any attention to a snuffy old woman who seems to have mistaken that shop for the tobacconist’s next door, and to be hopelessly waiting at the counter to be served with half an ounce of her favourite mixture. Wherever it is possible to express ugliness of feature, limb, or attitude, you have it expressed. Such men as the carpenters might be undressed in any hospital where dirty drunkards, in a high state of varicose veins, are received. Their very toes have walked out of Saint Giles’s."

On the 7th May, 1851, The Times accused John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Charles Allston Collins of “addicting themselves to a monkish style”, having a “morbid infatuation” and indulging in “monkish follies”. Finally, the works are dismissed as un-English, “with no real claim to figure in any

decent collection of English painting.” Six days later John Ruskin had a letter published in the newspaper, where he came to the defence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In another letter published on 30th May, Ruskin claimed that PRB “may, as they gain experience, lay in our land the foundations of a school of art nobler than has been seen for three hundred years”.

Ruskin now published a pamphlet entitled, Pre-Raphaelitism (1851). He argued hat the advice he had given in the first volume of Modern Painters had “at last been carried out, to the very letter, by a group of young men who... have been assailed with the most scurrilous abuse... from the public press.” Aoife Leahy has argued: "Ruskin’s defences had now taken a new and decidedly evangelical tone. he had formed friendships with the Pre-Raphaelite artists on the basis of his letters to The Times and, just as significantly, he had been personally harassed by members of the public for his views."

However, most art critics agreed with Dickens rather than Ruskin. As Lucinda Hawksley has pointed out: "Millais... was one of seven young artists, all of whom were Royal Academy trained, who formed a group called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (known as the PRB). They disagreed with many of the principles of art as defined by the rigid government of the Royal Academy and wanted to paint in the style that had been popular in Italy before the advent of Raphael. When the authorities and the public discovered - by an unfortunate chance - what the letters PRB stood for, they were furious at the group's perceived arrogance and actively turned against them, their followers and anyone who assumed a Pre-Raphaelite style of painting. It was several years before artists who painted in this style were accepted back into mainstream galleries. Millais was one of the fortunate few who was not ruined by the furore, largely because he was kept financially secure by family money."

Aoife Leahy has pointed out: "The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood itself lost its cohesion as a group in 1853 and no longer held meetings after this date. Ruskin, however, continued for some time to write about these same artists and the movement they had inspired in confident tones, with no note of disharmony. Fortunately, he had generally referred to the Pre-Raphaelites as a school and continued to do so in a seamless fashion. Having begun to defend the P.R.B. at a rather late stage, Ruskin seems to over-compensate by making no mention of the group’s break-up in his critical writings."

Primary Sources

(1) Lucinda Hawksley , Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens's Artist Daughter (2006)

Millais first grew to prominence over a scandal - a scandal associated with the artistic movement of which he was a founder member: Pre-Raphaelitism. He was one of seven young artists, all of whom were Royal Academy trained, who formed a group called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (known as the PRB). They disagreed with many of the principles of art as defined by the rigid government of the Royal Academy and wanted to paint in the style that had been popular in Italy before the advent of Raphael. When the authorities and the public discovered - by an unfortunate chance - what the letters PRB stood for, they were furious at the group's perceived arrogance and actively turned against them, their followers and anyone who assumed a Pre-Raphaelite style of painting. It was several years before artists who painted in this style were accepted back into mainstream galleries. Millais was one of the fortunate few who was not ruined by the furore, largely because he was kept financially secure by family money.

(2) Charles Dickens, Household Words (15th June, 1850)

This age is so perverse, and is so very short of faith in consequence, as some suppose, of there having been a run on that bank for a few generations that a parallel and beautiful idea, generally known among the ignorant as the Young England hallucination, unhappily expired before it could run alone, to the great grief of a small but a very select circle of mourners. There is something so fascinating, to a mind capable of any serious reflection, in the notion of ignoring all that has been done for the happiness and elevation of mankind during three or four centuries o slow and dearly-bought amelioration, that we have always thought it would tend soundly to the disapprovement of the general public, is any tangible symbol, any outward and visible sign, expressive of that admirable conception could be held up before them. We are happy to have found such a sign at last; and although it would make a very indifferent sign, indeed, in the Licensed Victualling sense of the word, and would probably be rejected with contempt and horror by any Christian publican, it has our warmest philosophical appreciation.

In the fifteenth century, a certain feeble lamp of art arose in the Italian town of Urbino. This poor light, Raphael Sanzio by name, better known to a few miserably mistaken wretches in these later days, as Raphael (another burned at the same time, called Titian), was fed with a preposterous idea of Beauty with a ridiculous power of etherealising, and exalting to the Very Heaven of Heavens, what was most sublime and lovely in the expression of the human face divine on Earth with the truly contemptible conceit of finding in poor humanity the fallen likeness of the angels of GOD, as raising it up again to their pure spiritual condition. This very fantastic whim effected a low revolution in Art, in this wise, that Beauty came to be regarded as one of its indispensable elements. In this very poor delusion, Artists have continued until the present nineteenth century, when it was reserved for some bold aspirants to "put it down."

The Pre-Raphael Brotherhood, Ladies and Gentlemen, is the dread Tribunal which is to set this matter right. Walk up, walk up and here, conspicuous on the wall of the Royal Academy of Art in England, in the eighty-second year of their annual exhibition, you shall see what this new Holy Brotherhood, this terrible Police that is to disperse all Post-Raphael offenders, has "been and done!"

You come in this Royal Academy Exhibition, which is familiar with the works of Wilkie, Collins, Etty, Eastlake, Mulready, Leslie, Maclise, Turner, Stanfield, Landseer, Roberts, Danby, Creswick, Lee, Webster, Herbert, Dyce, Cope, and others who would have been renowned as great masters in any age or country you come, in this place, to the contemplation of a Holy Family. You will have the goodness to discharge from your minds all Post-Raphael ideas, all religious aspirations, all elevating thoughts, all tender, awful, sorrowful, ennobling, sacred, graceful, or beautiful associations, and to prepare yourselves, as befits such a subject Pre-Raphaelly considered for the lowest depths of what is mean, odious, repulsive, and revolting.

You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England. Two almost naked carpenters, master and journeyman, worthy companions of this agreeable female, are working at their trade; a boy, with some small flavor of humanity in him, is entering with a vessel of water; and nobody is paying any attention to a snuffy old woman who seems to have mistaken that shop for the tobacconist’s next door, and to be hopelessly waiting at the counter to be served with half an ounce of her favourite mixture. Wherever it is possible to express ugliness of feature, limb, or attitude, you have it expressed. Such men as the carpenters might be undressed in any hospital where dirty drunkards, in a high state of varicose veins, are received. Their very toes have walked out of Saint Giles’s.

This, in the nineteenth century, and in the eighty-second year of the annual exhibition of the National Academy of Art, is the Pre-Raphael representation to us, Ladies and Gentlemen, of the most solemn passage which our minds can ever approach. This, in the nineteenth century, and in the eighty-second year of the annual exhibition of the National Academy of Art, is what Pre-Raphael Art can do to render reverence and homage to the faith in which we live and die! Consider this picture well. Consider the pleasure we should have in a similar Pre-Raphael rendering of a favourite horse, or dog, or cat; and, coming fresh from a pretty considerable turmoil about "desecration" in connection with the National Post Office, let us extol this great achievement, and commend the National Academy!

In further considering this symbol of the great retrogressive principle, it is particularly gratifying to observe that such objects as the shavings which are strewn on the carpenter’s floor are admirably painted; and that the Pre-Raphael Brother is indisputably accomplished in the manipulation of his art. It is gratifying to observe this, because the feat involves no low effort at notoriety; everybody knowing that it is by no means easier to call attention to a very indifferent pig with five legs, than to a symmetrical pig with four. Also, because it is good to know that the National Academy thoroughly feels and comprehends the high range and exalted purposes of Art; distinctly perceives that Art includes something more than the faithful portraiture of shavings, or the skilful colouring of drapery imperatively requires, in short, that it shall be informed with mind and sentiment; will on no account reduce it to a narrow question of trade-juggling with a palette, palette-knife, and paint-box. It is likewise pleasing to reflect that the great educational establishment foresees the difficulty into which it would be led, by attaching greater weight to mere handicraft, than to any other consideration even to considerations of common reverence or decency; which absurd principle, in the event of a skilful painter of the figure becoming a very little more perverted in his taste, than certain skilful painters are just now, might place Her Gracious Majesty in a very painful position, one of these fine Private View Days.

Would it were in our power to congratulate our readers on the hopeful prospects of the great retrogressive principle, of which this thoughtful picture is the sign and emblem! Would that we could give our readers encouraging assurance of a healthy demand for Old Lamps in exchange for New ones, and a steady improvement in the Old Lamp Market! The perversity of mankind is such, and the untoward arrangements of Providence are such, that we cannot lay that flattering unction to their souls. We can only report what Brotherhoods, stimulated by this sign, are forming; and what opportunities will be presented to the people, if the people will but accept them.

(3) Aoife Leahy, Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites in the 1850s (1999)

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood itself lost its cohesion as a group in 1853 and no longer held meetings after this date. Ruskin, however, continued for some time to write about these same artists and the movement they had inspired in confident tones, with no note of disharmony. Fortunately, he had generally referred to the Pre-Raphaelites as a school and continued to do so in a seamless fashion. Having begun to defend the P.R.B. at a rather late stage, Ruskin seems to over-compensate by making no mention of the group’s break-up in his critical writings. In his published notes on the Royal Academy exhibition of 1856, he pointed out that a significant change had taken place and his tone is almost ecstatic. His narrative seems to peak here, as his imagery is that of a Holy War between Raphael and the Pre-Raphaelites; “the battle is completely and confessedly won” as painters have abandoned Raphael, “struggling forward out of their conventionalism to the pre-Raphaelite standard”. The desired goal has been attained, as the majority of the exhibited works now show a clear Pre-Raphaelite influence and the Grand Style is no longer the accepted norm. The following year’s Academy notes would begin to register some disillusionment, but for now Ruskin was triumphant as the vindicated standard-bearer of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.