Ford Madox Brown

Ford Madox Brown was born in Calais in 1821. Brown studied art at Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, Rome and Paris before returning to England in 1845. Three years later Brown became friendly with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

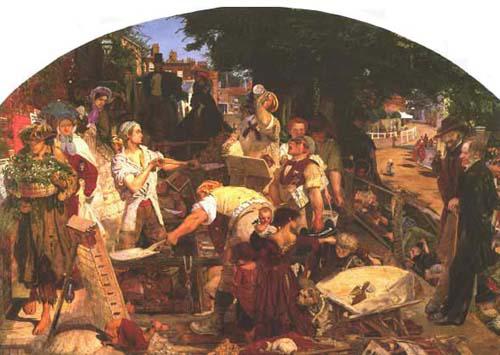

In 1852 Brown began work on what was to be the first serious attempt by a British artist to represent the working class in an urban environment. The painting shows the excavations for the laying of a sewage system in Hampstead.

The figures in the painting were based on the actual navvies that did the work. Also in the picture are two observers, F. D. Maurice and Thomas Carlyle. Maurice was the leader of the Christian Socialist movement and founder of the Working Men's College, an institution where Brown taught art.

Thomas Carlyle, like Maurice, was another man who Ford Madox Brown greatly admired. Brown had been influenced by Carlyle's view of the "nobleness and even sacredness of work". In the painting Brown attempted to capture what he believed was the "inherent dignity of the British labourer".

Although started in 1852 Work was not completed until 1865. Thomas Plint, a fervent supporter of the Temperance Society from Leeds, purchased the painting before it was finished in 1856. Plint also influenced the content of the picture by suggesting the inclusion of Thomas Carlyle and the women in the picture distributing Temperance tracts.

Another important painting produced by Ford Madox Brown at this time was The Last of England (1852-5). The picture shows the departure of Brown's friend, Thomas Woolner, for the Australian gold-fields.

Brown was also a close associate of William Morris and in 1861 was a founder member of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company. Brown main contribution was designing furniture and stained glass.

Ford Madox Brown completed twelve frescoes for Manchester Town Hall before his death in 1893.

Primary Sources

(1) In a catalogue that accompanied the first exhibition of Work in 1865, Ford Madox Brown described the background to the painting.

At that time extensive excavations, connected with the supply of water, were going on in the neighbourhood, and, seeing and studying daily as I did the British excavator, or navvy in the full swing of his activity (with his manly and picturesque costume, and with the rich glow of colour which exercise under a hot sun will impart), it appeared to me that he was at least as worthy of the powers of an English painter as the fisherman of the Adriatic, the peasant of the Campagna, or the Neapolitan lazzarone. Gradually this idea developed itself into that of Work as it now exists, with the British excavator for the central group, as the outward and visible type of Work.

(2) Thomas Plint, letter to Ford Madox Brown (November, 1856)

Cannot you introduce both Carlyle and Kingsley, and change one of the fashionable young ladies into a quiet, earnest, holy looking one, with a book or two and tracts? I want this put in, for I am much interested in this work myself, and know others who are.

(3) The Illustrated London News (1865)

Bravo! Mr. Brown, we would at once exclaim for the boldness of representing as your principal hero that potent agent in the work of British civilization, the excavator or navvy. We applaud, also, the variously suggestive, and by no means squeamish, way in which the theme Work is illustrated, positively and negatively. We applaud, we repeat, the honest effort to represent the actualities of workaday life.