Working Men's College

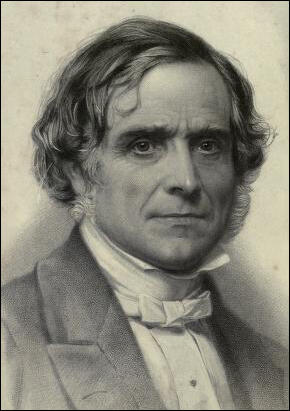

In May 1848 John Ludlow, Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley decided to publish a penny journal, Politics for the People, and this was considered the starting-point of the Christian Socialist movement. It was "sympathetic to the poor and based upon the acknowledgment that God rules in human society... They addressed themselves to workmen. They confessed that they were not workmen, but asked for workmen's help in bridging the gulf that divided them". (1) The paper only lasted till July, but the group continued to meet, generally in Ludlow's chambers, and a result of their discussions was the foundation of a night school in Little Ormond Yard. (2)

In 1852 Charles Blachford Mansfield argued that a Working Men's College was a natural development from the night classes in Little Ormond Yard. However, Mansfield failed to follow upon the idea. However, that winter several members of the group did provide lectures on a variety of different subjects. This included Frederick Denison Maurice on William Shakespeare, Walter Cooper on the genius of Robert Burns, George Frederick Robinson on entomology, John Pyke Hullah on how to start a singing class, Richard Chenevix Trench on Proverbs, and Frank Cranmer Penrose on architecture. (3)

Frederick Denison Maurice had always been more interested in education than economics and was especially interested in establishing a Working Men's College. Radical speeches by other Christian Socialists also caused problems from his employers. After one speech by Charles Kingsley, on 22nd June 1851, The principal of King's College wrote to him hoping that he would disown Kingsley's utterances, which he deplored as "reckless and dangerous". Although he did not agree completely with Kingsley he refused to criticise his old friend. (4)

The publication of Maurice's Theological Essays in 1853 provoked even more controversy. Richard William Jelf, the Principal of King's College, was concerned that Maurice was being attacked by almost every section of the religious establishment because of his outspoken social views. Jelf also objected to him being associated with George Holyoake, the main promoter of Secularism. Jelf asked Maurice to resign. He refused and demanded that he be either "acquitted or dismissed." He was dismissed. (5)

On the news of his dismissal, over a thousand working-men, representing around a hundred occupations, published a letter of support for Maurice. "That you may long continue to pursue your useful and honourable career: that the eminent services you have confessedly rendered to the Church and to the cause of education, may meet with a more generous and grateful appreciation; that those who at present misunderstand and misrepresent you may learn by your example and that they may at least emulate you in the wisdom and zeal with which you had advocated the cause of the working-man, is the sincere and earnest desire of those whose names are hereunto appended." (6)

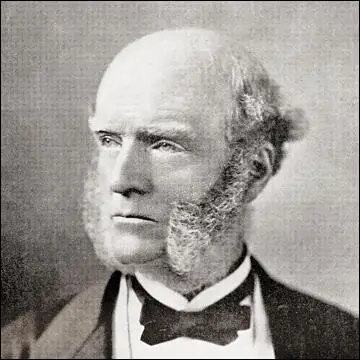

On reading the statement Maurice decided he would now put all his efforts into the formation of a Working Men's College. On 10th January, 1854, Maurice wrote to Charles Kingsley that he hoped that "my college" would soon be established. (7) The following day a meeting was held in Maurice's house that was attended by Thomas Hughes, Lloyd Jones and Edward Vansittart Neale, where it was agreed that the Promoters' Committee of Teaching and Publication be empowered to frame, and if possible carry out a plan to set up a People's College in London. (8)

Frederick Denison Maurice then drew up more concrete plans for a people's college that was to be founded in the premises of one of the failed associations at 31 Red Lion Square. In June and July a series of fund-raising lectures was given, and the college was ready for business in time for October, with a wide range of subjects and an interesting set of lecturers. The college was to be aimed specifically at the manual workers, and Maurice agreed to be Principle of the Working Men's College. (9)

It opened on 31st October 1854, with some 176 students. The most popular classes were Languages, English Grammar, Mathematics, Drawing whereas History, Law, Politics and the Physical Sciences attracted smaller attendance. Later the Working Men's College moved, first to Great Ormond Street and then to Crowndale Road. (10)

Some of the teachers at the college included Edward Vansittart Neale, John Ludlow, Thomas Hughes, Lloyd Jones, John Ruskin, Frederick James Furnival, Charles Blachford Mansfield, Lowes Cato Dickinson and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Founder member of the Christian Socialists, Charles Kingsley, never taught at the college but popularized it whenever he could. (11)

In October 1866 Frederick Denison Maurice became Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. However, he continued to run the Working Men's College in London, though he attended there less often. Maurice died at 6 Bolton Row, Piccadilly, on 1st April 1872. (12) He was replaced by Thomas Hughes who held the post until 1883. (13)

Primary Sources

(1) Statement signed by over a thousand working-men, representing around a hundred occupations, on the dismissal of Frederick Denison Maurice (27th December 1853)

That you may long continue to pursue your useful and honourable career: that the eminent services you have confessedly rendered to the Church and to the cause of education, may meet with a more generous and grateful appreciation; that those who at present misunderstand and misrepresent you may learn by your example and that they may at least emulate you in the wisdom and zeal with which you had advocated the cause of the working-man, is the sincere and earnest desire of those whose names are hereunto appended.

(2) Thomas Hughes, Memoir of a Brother (1873)

Accordingly a society was formed, chiefly of young barristers, under the presidency of the late Mr. Maurice, who was then Chaplain of Lincoln's Inn, for the purpose of establishing associations similar to those in Paris. It was called the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations, and I happened to be one of the original members, and on the Council. We were all full of enthusiasm and hope in our work, and of propagandist zeal: anxious to bring in all the recruits we could. I cannot even now think of my own state of mind at the time without wonder and amusement. I certainly thought (and for that matter have never altered my opinion to this day) that here we had found the solution of the great labour question; but I was also convinced that we had nothing to do but just to announce it, and found an association or two, in order to convert all England, and usher in the millennium at once, so plain did the whole thing seem to me. I will not undertake to answer for the rest of the Council, but I doubt whether I was at all more sanguine than the majority. Consequently we went at it with a will: held meetings at six o'clock in the morning (so as not to interfere with our regular work) for settling the rules of our central society, and its offshoots, and late in the evening, for gathering tailors, shoemakers, and other handicraftsmen, whom we might set to work; started a small publishing office, presided over by a diminutive one-eyed costermonger, a rough and ready speaker and poet (who had been in prison as a Chartist leader), from which we issued tracts and pamphlets, and ultimately a small newspaper; and, as the essential condition of any satisfactory progress, commenced a vigorous agitation for such an amendment in the law as would enable our infant Associations to carry on their business in safety, and without hindrance. We very soon had our hands full. Our denunciations of unlimited competition brought on us attacks in newspapers and magazines, which we answered, nothing loth. Our opponents called us Utopians and Socialists, and we retorted that at any rate we were Christians; that our trade principles were on all-fours with Christianity, while theirs were utterly opposed to it. So we got, or adopted, the name of Christian Socialists, and gave it to our tracts, and our paper. We were ready to fight our battle wherever we found an opening, and got support from the most unexpected quarters. I remember myself being asked by Mr. Senior, an old friend of your grandfather, to meet Archbishop Whately, and several eminent political economists, and explain what we were about. After a couple of hours of hard discussion, in which I have no doubt I talked much nonsense, I retired, beaten, but quite unconvinced. Next day, the late Lord Ashburton, who had been present, came to my chambers and gave me a cheque for £50 to help our experiment; and a few days later I found another nobleman, sitting on the counter of our shoemakers' association, arguing with the manager, and giving an order for boots.