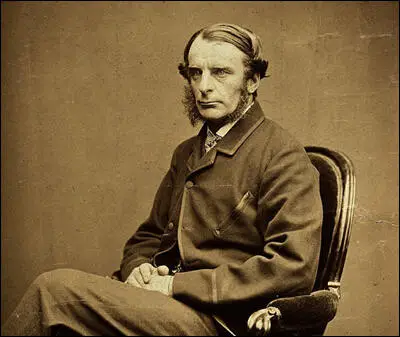

John Ludlow

John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow, the youngest in the family of two sons and three daughters of Lieutenant-Colonel John Ludlow of the East India Company, and his wife, Maria Jane Brown, was born in Neemuch, India, on 8th March 1821. His father died very shortly after the birth, and his mother took the family back to England, and then to France in 1826. From 1829 to 1838 he was educated at the Collège Bourbon in Paris. He visited Martinique where he developed a hatred of slavery. (1)

Ludlow returned to England, read law in the chambers of Charles Bellenden Ker, and was called to the bar at Lincoln's Inn on 21st November 1843. He practised as a conveyancer from 1843 to 1874, but had many interests outside the law. One of the first of these was the British India Society, an association for promoting reforms in India. At its inaugural meeting he heard and admired Daniel O'Connell. He attended a conference of Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, where he met Thomas Clarkson and Henry Brougham, and heard Thomas Carlyle lecture. In 1841 he visited Manchester, where he became acquainted with John Bright and Richard Cobden and a little later he became a member of the Anti-Corn Law League. (2)

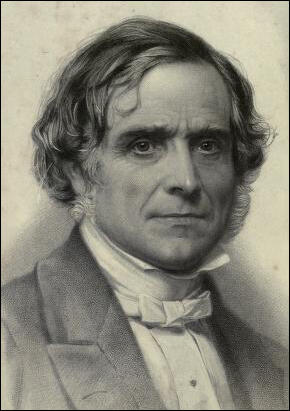

In 1848 John Ludlow met Charles Kingsley and later wrote: "I found his conversation fascinating by its originality, keen observation, strong sense and imaginative power; deep feeling and broad humour succeeding each other without giving the least sense of incongruity or jar to one's feelings. His stutter, which he felt most painfully himself as a thorn in the flesh, in fact only added to a raciness in his talk as one waited for what quaint saying was going to pour out, as it always did, at full speed, the stutter once conquered." (3)

On 10th April, 1848, a group of Christians who supported Chartism held a meeting in London. People who attended included John Ludlow, Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class. (4)

Feargus O'Connor had been making vicious attacks on other Chartist leaders such as William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, Bronterre O'Brien and Henry Vincent who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor became the leader of what became known as the Physical Force Chartists, Disturbed by these events members of the Christian Socialist movement volunteered to become special constables at these demonstrations. (5) Ludlow later wrote: "The present generation has no idea of the terrorism which was at that time exercised by the Chartists." (6)

In May 1848 Ludlow, Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley decided to publish a penny journal, Politics for the People, and this was considered the starting-point of the Christian Socialist movement. It was "sympathetic to the poor and based upon the acknowledgment that God rules in human society... They addressed themselves to workmen. They confessed that they were not workmen, but asked for workmen's help in bridging the gulf that divided them". (7) The paper only lasted till July, but the group continued to meet, generally in Ludlow's chambers, and a result of their discussions was the foundation of a night school in Little Ormond Yard. (8)

Frederick Denison Maurice declared that the term "Christian Socialism" would "commit us at once to the conflict we must engage in sooner or later with the unsocial Christians and the unchristian socialists." (9) Percy Redfern has argued that the Christian Socialists disapproved of the socialism promoted by Robert Owen: "The idea of co-operation, which Owen had proclaimed, was now by most people despised and rejected. The Christian Socialists meant to glorify the Christian idea of brotherhood which they found at the core of it; while, with equal force, they declared themselves not Owenites." (10)

John Ludlow who had been influenced by the socialist writer, Henri de Saint-Simon, became an important figure in the group. He sought to Christianize Socialism as he believed structural change was needed and charity was not enough. He had been a social worker in London and had commented: "It seemed to me that no serious effort was made to help a person out of his or her misery, but only to help him or her in it." (11)

Colin Matthew has argued that it could be argued that "Ludlow may reasonably be taken as the actual founder of the movement: it was his experience from 1847 of social visiting among the London poor, and his knowledge of the French co-operatives, which gave content to Maurice's theological groundwork. Whereas Maurice was always reluctant to involve himself in practical agitation and action, Ludlow was a concrete thinker who was never satisfied until ideals received some sort of institutional expression. Despite adopting the political label of socialism, however, he was always insistent that social reform rather than political organization was the appropriate priority for nineteenth-century England. He was a convinced democrat and, unlike the other Christian socialists, he had a genuine vision of social transformation." (12)

Chris Bryant has suggested that "Ludlow had perhaps the most secure political understanding of all the Christian Socialists. He had seen some of the early socialist experiments in Paris, he understood the British parliamentary system, he knew how associations could be framed in law and, above all, by virtue of his French upbringing he could maintain a degree of distance from the British political and ecclesiastical scene that meant he could study it without the concerns for preferment that tormented Kingsley or the instinct for appeasement that motivated Maurice." (13)

In December 1849 Ludlow and his friends drew up the first code of rules in Britain for a working people's co-operative society. In 1850 John Ludlow founded and edited a penny weekly paper called the Christian Socialist, which appeared from 2nd November, 1850 to 28th June 1851. It promoted the Christian view of a socialist society. Ludlow as the editor began to diffuse the principles of co-operation by the practical application of Christianity to the purposes of trade and industry. (14)

Christian Socialists began offering lectures in 1853 for working men and women in Castle Street East (by Oxford Street), and Ludlow conducted there a successful French class. From these, and partly in consequence of a resolution of a conference of delegates from co-operative bodies, the Working Men's College in Great Ormond Street arose in November 1854. Ludlow was the chief practical worker in its foundation. He lectured there on law, on English, and on the history of India. (15)

Edward Vansittart Neale was another important figure in the Christian Socialist movement. Matthew Lee has suggested: "Neale was central in shifting the focus of the movement from promotion of self-governing workshops to co-operation on a larger scale. He funded and founded the first London co-operative stores in Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, and advanced capital for two unsuccessful builders' associations. Initially ignorant of northern co-operation on the Rochdale and redemptionist models, Neale became a swift convert to consumers' co-operation and became allied with many former Owenites." (16)

Neale's support of cooperative stores brought him into conflict with other Christian Socialists like John Ludlow because he challenged the assumption that all associations had to be producer co-operatives rather than consumer ones. Thomas Hughes supported Neale, but Ludlow was furious seeing it as a betrayal of the fundamental principles of the Society. Ludlow presented an ultimatum at the Promoters' Council meeting, that either Neale and Hughes went or he did. However, Frederick Denison Maurice, managed to persuade Ludlow to withdraw the threat. (17)

John Ludlow has been described as "a small, slightly built man of mild manners, a finely shaped head, and very bright, brown eyes." Ludlow was always energetic, and in addition to his legal and lecturing work maintained a steady flow of publications on a variety of subjects, and published many articles in the Edinburgh Review, Fraser's Magazine, Macmillan's Magazine, The Contemporary Review and The Fortnightly Review. (18)

In 1865 Ludlow came into conflict with some Christian Socialists over the case of John Edward Eyre, the British Governor of Jamaica. Eyre had suppressed the Morant Bay Rebellion. Up to 439 black people were killed in the reprisals, some 600 flogged, and about 1000 houses burnt down. Ludlow and Thomas Hughes. helped form the Jamaica Committee in criticism of Eyre's excessive violence, while Charles Kingsley, Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin defended the actions of Eyre. Ludlow saw Kingsley's views as tantamount to a vicious racism and resolved to sever connections with him. (19)

In 1869 Ludlow married his cousin, Maria Sarah, daughter of Gordon Forbes of Ham Common. They had been close friends for 26 years before they were married. They had no children. (20)

In 1870 Ludlow was appointed secretary to the Royal Commission on Friendly and Benefit Building Societies, and from 1874 until 1891 he was chief registrar of friendly societies - years he described as "the happiest of my life". To the very end of his long life he continued to be consulted about these types of issues, and lived to be present at the Pan Anglican Congress of 1908, at which so many of his ideals were acclaimed. (21)

John Ludlow died at his home, 35 Upper Addison Gardens, London, on 17 October 1911.

Primary Sources

(1) Chris Bryant, Possible Dreams: A Personal History of the British Christian Socialist (1996)

Heavily scriptural in his approach, he (John Ludlow) was distrustful of much of the narrowness of many evangelicals.... His socialism, as his faith, was heavily influenced by his still regular trips to France. He came into contact with Fourier, whose collective corporations, called phalansteres, he believed pointed the way to a more harmonious economic life, and on studying political economy in 1838 he found it to be a "let-alone" philosophy that left humanity adrift on an open sea.

(2) Norman Moore, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1912)

Ludlow was a small, slightly built man of gentle manners. He had a finely shaped head and brown eyes of peculiar brightness. He was active in mind and body to the end. The 'constans et perpetua voluntas' of Justinian animated his whole life. He was always ready to sacrifice everything in support of his principles. His reputation for knowledge of the part of the law which interested him was high. He was learned in both men and books, and knew more than a dozen languages. His political creed was based on faith in the people. He was firmly attached to Christianity, and his deep religious feelings were apparent in his speeches, writings, and conduct, and are illustrated in a short account which exists in manuscript of seven great crises in his spiritual and moral life.

Student Activities

References

(1) Colin Matthew, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

(2) Norman Moore, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1912)

(3) John Ludlow, The Autobiography of a Christian Socialist (1981) page 65

(4) Alan Wilkinson, Christian Socialism (1998) page 16

(5) Chris Bryant, Possible Dreams: A Personal History of the British Christian Socialist (1996) page 34

(6) John Ludlow, The Autobiography of a Christian Socialist (1981) page 65

(7) Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church (1966) page 352

(8) Norman Moore, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1912)

(9) Frederick Denison Maurice, letter to John Ludlow (January, 1850)

(10) Percy Redfern, The Story of the CWS: 1863-1913 (1913) page 10

(11) Alan M. Suggate, William Temple and Christian Social Ethics Today (1987) page 20

(12) Colin Matthew, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

(13) Chris Bryant, Possible Dreams: A Personal History of the British Christian Socialist (1996) page 40

(14) Norman Moore, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1912)

(15) Colin Matthew, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

(16) Matthew Lee, Edward Vansittart Neale: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (26th May 2005)

(17) Chris Bryant, Possible Dreams: A Personal History of the British Christian Socialist (1996) page 54

(18) Colin Matthew, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

(19) Chris Bryant, Possible Dreams: A Personal History of the British Christian Socialist (1996) page 65

(20) Colin Matthew, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

(21) Norman Moore, John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (1912)