Anti-Corn Law League

A Corn Law was first introduced in Britain in 1804, when the landowners, who dominated Parliament, sought to protect their profits by imposing a duty on imported corn. During the Napoleonic Wars it had not been possible to import corn from Europe. This led to an expansion of British wheat farming and to high bread prices.

Farmers feared that when the war came to an end in 1815, the importation of foreign corn would lower prices. This fear was justified and the price of corn reached fell from 126. 6d. a quarter in 1812 to 65s. 7d. three years later. British landowners applied pressure on members of the House of Commons to take action to protect the profits of the farmers. Parliament responded by passing a law permitting the import of foreign wheat free of duty only when the domestic price reached 80 shillings per quarter (8 bushels). During the passing of this legislation, Parliament had to be defended by armed troops against a large angry crowd.

This legislation was hated by the people living in Britain's fast-growing towns who had to pay these higher bread prices. The industrial classes saw the Corn Laws as an example of how Parliament passed legislation that favoured large landowners. The manufacturers in particular was concerned that the Corn Laws would result in a demand for higher wages.

In 1828 William Huskisson sought to relieve the distress caused by the high price of bread by introducing a sliding scale of duties according to price. A trade depression in 1839 and a series of bad harvests created a great deal of anger towards the Corn Laws.

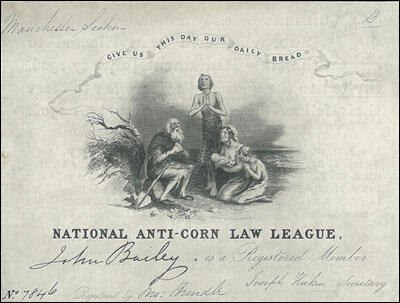

In October 1837, Joseph Hume, Francis Place and John Roebuck formed the Anti-Corn Law Association in London. The following year Richard Cobden joined with Archibald Prentice to establish a branch of this organisation in Manchester. In March 1839 Cobden was instrumental in establishing a new centralized Anti-Corn Law League. Cobden was now able to organize a national campaign in favour of reform.

Cobden was a friend of John Bright and suggested he should join the League. Bright agreed and over the next few years he toured the country giving speeches on the need to reform the Corn Laws. Bright was an outstanding orator and he drew large crowds wherever he appeared. In his speeches Bright attacked the privileged position of the landed aristocracy and argued that their selfishness was causing the working class a great deal of suffering. Bright appealed to the working and middle classes to join together in the fight for free trade and cheaper food.

In 1841 General Election the leader of the Anti-Corn Law League, Richard Cobden became the MP for Stockport. Although Cobden continued to tour the country making speeches against the Corn Laws, he was now in a position to constantly remind the British government that reform was needed.

The economic depression of 1840-1842 increased membership of the Anti-Corn Law League and Richard Cobden and John Bright spoke to very large audiences all over the country. By 1845 the League, with support from wealthy industrialists such as Peter Taylor and Samuel Courtauld, was the wealthiest and best organised political group in Britain.

The failure of the Irish potato crop in 1845 and the mass starvation that followed, forced Sir Robert Peel and his Conservative government to reconsider the wisdom of the Corn Laws. Irish nationalists such as Daniel O'Connell also became involved in the campaign. Peel was gradual won over and in January 1846 a new Corn Law was passed that reduced the duty on oats, barley and wheat to the insignificant sum of one shilling per quarter became law.

Primary Sources

(1) The Quarterly Review reported on a Anti-Corn Law League on 5th July, 1842.

The Chairman, the same as at the former London conference, Mr. Peter Taylor, said "The cry of suffering and distress would make itself heard, and if that distress were not speedily relieved, he believed this distress would make itself heard in a voice of thunder which woulf frighten the government and the legislature from its propriety.

(2) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

During the period I spent in Birmingham, John Bright was one of the three Members of Parliament for the borough. I frequently heard him in the Birmingham Town Hall. I have heard many prominent speakers in the hall, and in many other places, but never one comparable to John Bright. The plainness of his language, the unaffected simplicity of his illustrations, his power to drive home the points of his speech, in conjunction with the mellifluous vocalization of which he was master, made one feel that it was a great privilege to listen to such oratory, and to observe the orator.