Samuel Courtauld

Samuel Courtauld, the son of George Courtauld, was born in Albany, New York, in 1793. The family moved to England in 1793 and by 1809 Samuel had his own silk mill in Braintree, Essex.

In 1818 George Courtauld went to live in America and left Samuel to run the silk mill. Samuel expanded the business, building two more mills in nearby Halstead and Bocking. In 1825 Courtauld installed a steam-engine at his mill in Bocking. He also invested heavily in power looms and by 1835 had 106 of these machines in his mill at Halstead.

Like his father, Samuel Courtauld was a Unitarian, who favoured social reform. However, he was opposed to the 1833 Factory Act, arguing that: "Legislative interference in the arrangement and conduct of business is always injurious, tending to check improvement and to increase the cost of production." If Parliament insisted on passing legislation, Courtauld suggested it should only attempt to protect children under ten.

Courtauld argued that legislation was only acceptable when it could be shown that children were being badly treated, however, this was not the case in the silk industry. Courtauld claimed that: "No children among the poor in this neighbourhood are more healthy than those employed in factories."

Courtauld, like all silk manufacturers, was heavily dependent on young female workers. In 1838 over 92% of his workforce were female. The high percentage of women workers helped to keep Courtauld's labour costs down. Whereas adult males at Courtauld's mills earned 7s. 2d., women were paid less than 5s. a week. The cheapest of all were girls under 11 who received only 1s. 5d. a week.

Courtauld was a strong supporter of the Whigs and in the early 1830s considered the possibility of becoming a candidate for the House of Commons. He supported the 1832 Reform Act and was also involved in the Nonconformist campaign against the paying of church rates. Like most Unitarians, Courtauld objected to paying rates for the upkeep of Anglican churches. In the 1840s Courtauld was active in the Anti-Corn Law League and spoke at public meetings in favour of granting of full civil and political rights to the Jewish community in Britain.

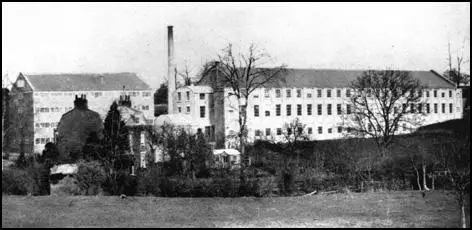

old mill built in 1809 can be seen on the left of the picture.

By 1850 Courtauld employed over 2,000 people in his three silk mills. Courtauld produced a variety of different silks but his main activity was the production of crepe, which became very fashionable in the second-half of the 19th century and was the main dress material worn, by upper and middle-class women after the death of a relative.

As this business expanded, Samuel Courtauld recruited partners including his brother, George Courtauld II (1802-1861) and Peter Alfred Taylor (1819-1891). Both men were Unitarians and active in social reform. Taylor, a leading figure in the Anti-Corn Law League, eventually became M.P. for Leicester.

Between 1830 and 1880 the average level of profits of the company increased by 1,400 per cent. During the same period, wages only rose by 50 per cent. By the 1870s Courtauld was a wealthy man with an annual income of £46,000 and a fortune approaching £700,000.

Attempts were made by the workers to share some of these extra profits. However, when his power-loom weavers at Halstead went on strike in 1860 he refused to negotiate with them. Courtauld, who was opposed to trade unions, described the men's actions as a "vain attempt at intimidation." He told his mill manager to: "report to me the names of the 20 to 50 of those who have been foremost in this shameful disorder, for immediate and absolute discharge."

When Courtauld recruited Peter Alfred Taylor as a partner in 1849 he decided to take a less active role in the business. His increasing deafness made work difficult and so he planned to spend more time on his 3,200 acres Gosfield Hall estate near Halstead. However, Samuel Courtauld found it impossible to retire and continued to play a dominant role in the company until just before his death in 1881.

Primary Sources

(1) Samuel Courtauld, speech in 1833 on proposed factory legislation.

The real hardship of the labouring poor here (silk mills in Essex) is rather the want of adequate employment than its severity; and the really painful task of a master manufacturer is the daily necessity of refusing employment to numbers of famishing applicants.

Legislative interference in the arrangement and conduct of business is always injurious, tending to check improvement and to increase the cost of production.

(2) Samuel Courtauld, evidence to Parliamentary Committee (1834)

Factory hours are comparatively few, and the factory employment is light; but the hand-weavers at their own homes sit in a confined posture for many more hours, their appearance is pallid and overwrought, and they are really entitled to the most benevolent consideration, and their cry and just demand is for cheap bread. May the wisdom of the legislature grant them relief.

(3) When interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee in 1834, Samuel Courtauld explained how his company controlled its young workers.

We use a regular system of forfeits and rewards, the stimulus of piece-work, and dismissal in the last resort. Formerly, something like a system of slight chastisement, connected with a system of task-work was adopted.

(4) When interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee in 1840, Samuel Courtauld explained why silk manufacturers used hand-loom weavers.

The crape manufacturer does a great portion of his work in power-loom factories; but he also gives out work to hand-loom weavers. Whenever there is a slackness of trade he discontinues his hand-loom weavers; a part of them at any rate, or perhaps the whole of them. The weavers being dismissed, put him to no expense. But he continues on his power looms, because in them he has capital embarked, the interest of which he cannot afford to lose. When trade becomes brisk, he again employs his hand-loom weavers.

(5) In 1860 the power-loom weavers at Halstead went on strike. Samuel Courtauld instructed his mangers how to deal with the situation.

They have chosen to strike. This vain attempt at intimidation makes it impossible for us to confer with them in the friendly spirit in which they must know in their hearts we have always acted towards them.

If by the breakfast hour they do not come in, close all the factories for the whole week. And if by the end of the week they are still idle, we shall take instant and vigorous measures to get large portions of our goods permanently made in other parts of England. Meanwhile report to me the names of the 20 to 50 of those who have been foremost in this shameful disorder, for immediate and absolute discharge.

(6) Employment at Courtauld's Bocking & Halstead mills in 1838.

Males

Females

Total

Males &

Females

13 & under

14-18

19 & above

Total

13 & under

14-18

19 & above

Total

Bocking

9

6

-

15

24

93

91

208

223

Halstead

28

17

20

65

15

98

212

325

390

Total

37

23

20

80

39

191

303

533

613

(7) Power-looms at Courtauld's Halstead Mill.

Year

Power-Looms

1829

10

1836

106

1838

178

1840

243

1845

477

1850

570

(8) Courtauld & Co Profits (1835-1885)

Year

Profits (£)

1835

2,075

1840

5,112

1845

26,520

1850

39,518

1855

43,952

1860

20,313

1865

61,005

1870

91,067

1875

93,195

1880

82,151

1885

110,633