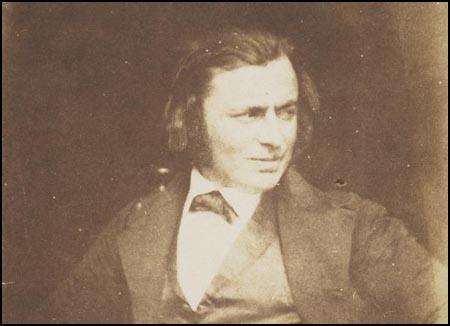

Henry Vincent

Henry Vincent, the son of Thomas Vincent, a goldsmith, was born at High Holban on 10th May, 1813. Thomas Vincent's business failed when Henry was a boy and the family moved to Hull.

In 1828 Henry became an apprentice printer and soon afterwards joined a Tom Paine discussion group. Henry Vincent was particularly influenced by Paine's ideas on universal suffrage and welfare benefits.

After completing his apprenticeship in 1833, Vincent moved back to London where he obtained employment as a printer. He continued to be active in politics and in 1836 he joined the recently formed London Working Mens' Association. By 1837 he had developed a reputation as one of the best orators involved in the promotion of universal suffrage. In the summer of 1837 Vincent and John Cleave went on a speaking tour of Northern England and helped establish Working Mens' Associations in Hull, Leeds, Bradford, Halifax and Huddersfield.

In 1838 Vincent concentrated his efforts in recruiting supporters for the Charter in the West Country and South Wales. He was not always welcomed by local people and in Devizes he was attacked and knocked unconscious. However, he was very successful in persuading people in mining communities to join the movement.

The authorities became concerned about Vincent's ability to convert working people to the ideas of universal suffrage. They were particularly worried by his warnings that the Chartists might be forced to use Physical Force to win the vote. Vincent was followed around by government spies and in May 1838 he was arrested for making inflammatory speeches. On 2nd August he was tried at Monmouth Assizes and sentenced to twelve months imprisonment. Vincent was denied writing materials and only allowed to read books on religion. The Newport Rising that took place in November 1839 was partly a protest at the treatment Henry Vincent was receiving in prison.

Soon after his release from prison Vincent was rearrested and charged with using "seditious language". He conducted his own defence but he was found guilty and he received another 12 months sentence. While in prison Vincent was visited regularly by Francis Place who gave him lessons in French, history and political economy.

After his release from prison in January, 1841, Henry Vincent married Lucy Cleave, the daughter of John Cleave, the editor of the Working Man's Friend. Henry and Lucy set up home in Bath and began publication of the National Vindicator.

Henry Vincent continued to tour the country making speeches on behalf of universal suffrage. However, he had now abandoned the idea of Physical Force and gave his support to William Lovett and the Moral Force Chartists. Vincent now talked at meetings of "quietly revolutionizing our country". Like Lovett, Vincent believed that Chartists needed to concentrate on the "mental and moral improvement" of working people. At his various meetings, Vincent attempted to link the Chartist movement with the Temperance Society and helped form several teetotal political societies.

Although Henry Vincent and Fergus O'Connor had been close allies they disagreed about temperance andPhysical Force and the two men drifted apart. In in 1842 Vincent helped form the Complete Suffrage Union. Although Vincent remained a member of the National Charter Association, O'Connor saw this as a betrayal and this finally brought an end to their friendship.

The National Vindicator ceased publication in 1842 but Vincent continued to give lectures on a wide variety of different subjects. He also stood, unsuccessfully, as an independent Radical at Ipswich (1842 and 1847), Tavistock (1843), Kilmarnock (1844), Plymouth (1846) and York (1848 and 1852).

A supporter of the anti-slavery movement in America, Vincent was invited to make several lecture tours in that country (1866, 1867 and 1875-76). He always took an interest in international politics and in 1876 was very active in the campaign against the Bulgarian atrocities. Henry Vincent died on 29th December, 1878.

Primary Sources

(1) Bronterre O'Brien, London Mercury (4th March, 1837)

Henry Vincent, a young and very ardent republican is, I believe, a great favourite among his brother operatives; at any rate, he is one of the their most effective speakers, and well deserving the applause so frequently and liberally bestowed on him. I had heard him on a few previous occasions, but the meeting on Tuesday called forth the full extent of his powers. He spoke with boldness, fluency and a perfect command of the subject. Paine is evidently a great favourite with him, for not only does he delight in recommending the writer, but he has all the best maxims and arguments at his fingers' ends. Amongst many other good things, he gave a masterly exposition of the "rotten House of Commons".

(2) R. G. Gammage, History of the Chartist Movement (1894)

The man who, above all the leaders of the Association, was calculated to wield an influence in the provinces was Henry Vincent. His person was extremely graceful, and he appeared on the platform to considerable advantage. With a fine flexible voice, a florid complexion, and, excepting in intervals of passion, a most winning expression he had only to present himself in order to win all hearts over to his side. His attitude was perhaps the most easy and graceful of any popular orator of the time. For fluency of speech he rivalled all his contemporaries, few of him were anxious to stand beside him on the platform. With the fair sex his slight handsome figure, the merry twinkle of his eye, his incomparable mimicry, his passionate bursts of enthusiasm, the rich music of his voice, and, above all, his appeals for the elevation of women, rendered him an universal favourite.