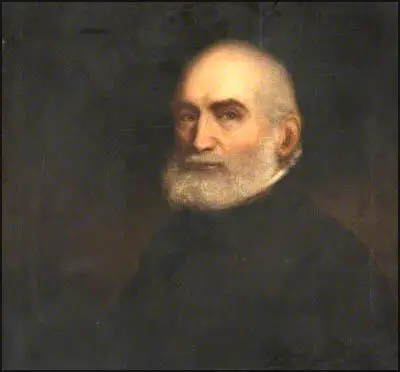

Robert Owen

Robert Owen, the son of Robert Owen a saddler and ironmonger from Newtown in Wales, was born on 14th May, 1771. His mother, Anne Williams, was a farmer's daughter. Robert, the youngest of seven children, was an intelligent boy who did very well at his local school. Owen was later to recall that "he disliked competition and prizes in sports, because it made the losers unhappy." (1)

When he was seven years old his schoolmaster, William Thickens, employed him as his assistant. It gave him some first-hand experience of teaching and probably influenced his ideas about education. (2) "At this period I was fond of and had a strong passion for reading everything which fell in my way". (3)

At the age of ten, Owen's father sent him to work in a large drapers in Stamford, Lincolnshire. In 1784 Owen joined a London retailer, working twelve hours daily for £25 a year, and then moved to a similar position at £40 a year under in Manchester. (4)

During this period he heard about the success Richard Arkwright was having with his textile factory in Cromford. Robert was quick to see the potential of this way of manufacturing cloth and although he was only nineteen years old, borrowed £100 and set up a business as a manufacturer of spinning mules with John Jones, an engineer. He sold his share in the business in 1789 and soon afterwards went to manage a mill with 500 employees owned by Peter Drinkwater, who had first applied the Boulton and Watt engine to cotton spinning. (5)

Owen applied himself rigorously, spending six weeks studying the factory, and proposing many refinements to the manufacturing process. This was highly successful and the company became well-known for the quality of the thread. Owen met a lot of businessmen involved in the textile industry. This included David Dale, the owner of Chorton Twist Company in New Lanark, Scotland, the largest cotton-spinning business in Britain. The two men became close friends and in 1799 Robert married Dale's daughter, Caroline. (6)

New Lanark

With the financial support of several businessmen from Manchester, in 1810 Owen purchased Dale's four textile factories in New Lanark for £60,000. Under Owen's control, the Chorton Twist Company expanded rapidly. However, Robert Owen was not only concerned with making money, he was also interested in creating a new type of community at New Lanark. He became highly critical of factory owners to employ young children: "In the manufacturing districts it is common for parents to send their children of both sexes at seven or eight years of age, in winter as well as summer, at six o'clock in the morning, sometimes of course in the dark, and occasionally amidst frost and snow, to enter the manufactories, which are often heated to a high temperature, and contain an atmosphere far from being the most favourable to human life, and in which all those employed in them very frequently continue until twelve o'clock at noon, when an hour is allowed for dinner, after which they return to remain, in a majority of cases, till eight o'clock at night." (7)

Owen set out to make New Lanark an experiment in philanthropic management from the outset. Owen believed that a person's character is formed by the effects of their environment. Owen was convinced that if he created the right environment, he could produce rational, good and humane people. Owen argued that people were naturally good but they were corrupted by the harsh way they were treated. For example, Owen was a strong opponent of physical punishment in schools and factories and immediately banned its use in New Lanark. (8)

David Dale had originally built a large number of houses close to his factories in New Lanark. By the time Owen arrived, over 2,000 people lived in New Lanark village. One of the first decisions took when he became owner of New Lanark was to order the building of a school. Owen was convinced that education was crucially important in developing the type of person he wanted. He stopped employing children under ten and reduced their labour to ten hours a day. The young children went to the nursery and infant schools that Owen had built. Older children worked in the factory but also had to attend his secondary school for part of the day. (9)

George Combe, an educator who was unsympathetic to Owen's views generally, visited New Lanark during this period. "We saw them romping and playing in great spirits. The noise was prodigious, but it was the full chorus of mirth and kindliness." Combe explained that Owen had ordered £500 worth of "transparent pictures representing objects interesting to the youthful mind" so that children could "form ideas at the same time that they learn words". Combe went on to argue that the greatest lessons Owen wished the children to learn were "that life may be enjoyed, and that each may make his own happiness consistent with that of all the others." (10)

Margaret Cole has carried out a special study of Robert Owen's educational ideas: "He (Owen) thought education should be natural and spontaneous and the children should enjoy it. He set little store, in the early stage, by learning out of books, but believed that children should learn by means of free discussion, question and answer, by exploration and study of the countryside, and by extensive provision of pictures, maps and charts, and what we should now call Visual Aids... He did not believe in seating children in tidy rows, but letting them roam about freely, in learning to sing and to dance the dances of all countries... He forbade any sort of punishment or even 'harsh critical words', and the strength of his personality, coupled with his love for all children and gift for managing them, secured that neither he nor the teachers who eventually he employed had any trouble with discipline." (11)

The journalist, George Holyoake, became a great supporter of Owen's work in New Lanark: "At New Lanark he virtually or indirectly supplied to his workpeople, with splendid munificence and practical judgment, all the conditions which gave dignity to labour.... Co-operation as a form of social amelioration and of profit existed in an intermittent way before New Lanark; but it was the advantages of the stores Owen incited that was the beginning of working-class co-operation. His followers intended the store to be a means of raising the industrious class, but many think of it now merely as a means of serving themselves. Still, the nobler portion are true to the earlier ideal of dividing profits in store and workshop, of rendering the members self-helping, intelligent, honest, and generous, and abating, if not superseding competition and meanness." (12)

Child Labour

When Owen arrived at New Lanark children from as young as five were working for thirteen hours a day in the textile mills. Owen later explained to a parliamentary committee: "I found that there were 500 children, who had been taken from poor-houses, chiefly in Edinburgh, and those children were generally from the age of five and six, to seven to eight. The hours at that time were thirteen. Although these children were well fed their limbs were very generally deformed, their growth was stunted, and although one of the best schoolmasters was engaged to instruct these children regularly every night, in general they made very slow progress, even in learning the common alphabet." (13)

Owen's partners were concerned that these reforms would reduce profits. Frederick Adolphus Packard explained that when they complained in 1813 he replied: "that if he was to continue to act as managing partner he must be governed by the principles and practices." Unable to convince them of the wisdom of these reforms, Owen decided to borrow money from Archibald Campbell, a local banker, in order to buy their share of the business. Later, Owen sold shares in the business to men who agreed with the way he ran his factory. This included Jeremy Bentham and Quakers such as William Allen, Joseph Foster and John Walker. (14)

Robert Owen hoped that the way he treated children at his New Lanark would encourage other factory owners to follow his example. It was therefore important for him to publicize his activities. He wrote several essays including The Formation of Character (1813) that looked into the role of education in society. "The governing powers of all countries should establish rational plans for the education and general formation of the characters of their subjects... These plans must be devised to train children from their earliest infancy in good habits... Such habits and education will impress them with an active and ardent desire to promote the happiness of every individual." (15)

This was followed by A New View of Society (1814). In these two essays Robert he demanded a system of national education to prevent idleness, poverty, and crime among the "lower orders". He also recommended restricting "gin shops and pot houses, the state lottery and gambling, as well as penal reform, ending the monopolistic position of the Church of England, and collecting statistics on the value and demand for labour throughout the country." (16)

During this period Owen made about fifty visits to the philosophical anarchist and religious sceptic William Godwin, who was the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792). Godwin had been a great influence on people such as Richard Price, Joseph Priestley, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. (He fell out with Shelley when he eloped with sixteen-year-old daughter, Mary Godwin.) Over many years had argued that the evil actions of men are solely reliant on the corrupting influence of social conditions, and that changing these conditions could remove the evil in man. (17)

In January 1816, Robert Owen made a speech at a meeting in New Lanark: "When I first came to New Lanark I found the population similar to that of other manufacturing districts... there was... poverty, crime and misery... When men are in poverty they commit crimes... instead of punishing or being angry with our fellow-men... we ought to pity them and patiently to trace the causes... and endeavour to discover whether they may not be removed. This was the course which I adopted". (18)

Robert Owen sent detailed proposals to Parliament about his ideas on factory reform. This resulted in Owen appearing before Robert Peel and his House of Commons committee in April, 1816. Owen explained that when he took over the company they employed children as young as five years old: "Seventeen years ago, a number of individuals, with myself, purchased the New Lanark establishment from Mr. Dale.... I came to the conclusion that the children were injured by being taken into the mills at this early age, and employed for so many hours; therefore, as soon as I had it in my power, I adopted regulations to put an end to a system which appeared to me to be so injurious". (19)

In his factory Owen installed what became known as "silent monitors". These were multi-coloured blocks of wood which rotated above each labourer's workplace; the different coloured sides reflected the achievements of each worker, from black denoting poor performance to white denoting excellence. Employees with illegitimate children were fined. One-sixtieth of wages was set aside for sickness, injury, and old age. Heads of households were elected to sit as jurors to judge cases respecting the internal order of the community. (20)

Robert Owen came under attack from those who objected to the capitalist system of manufacturing. In August 1817, Thomas Wooler wrote an article about Owen in his radical newspaper Black Dwarf: "It is very amusing to hear Mr Owen talk of re-moralizing the poor. Does he not think that the rich are a little more in want of re-moralizing; and particularly that class of them that has contributed to demoralize the poor, if they are demoralized, by supporting measures which have made them poor, and which now continue them poor and wretched? Talk of the poor being demoralized! It is their would-be masters that create all the evils that afflict the poor, and all the depravity that pretended philanthropists pretend to regret."

Wooler went on to argue: "Let him abandon the labourer to his own protection; cease to oppress him, and the poor man would scorn to hold any fictitious dependence upon the rich. Give him a fair price for his labour, and do not take two-thirds of a depreciated remuneration back from him again in the shape of taxes. Lower the extravagance of the great. Tax those real luxuries, enormous fortunes obtained without merit. Reduce the herd of locusts that prey upon the honey of the hive, and think they do the bees a most essential service by robbing them. The working bee can always find a hive. Do not take from them what they can earn, to supply the wants of those who will earn nothing. Do this; and the poor will not want your splendid erections for the cultivation of misery and the subjugation of the mind." (21)

Robert Owen toured the country making speeches on his experiments at New Lanark. He also publishing his speeches as pamphlets and sent free copies to influential people in Britain. In one two month period he spent £4,000 publicizing his activities. In his speeches, Owen argued that he was creating a "new moral world, a world from which the bitterness of divisive sectarian religion would be banished". As one of his supporters pointed out that to argue that "all the religions of the world" to be wrong was "met by outrage". (22)

On 14th August 1817, Robert Owen addressed an audience of many hundreds at the City of London tavern. Leading members of the clergy and government were present. So also were political economists and significant figures in the reform movement. Owen called for Parliament to pass legislation to protect the poor. He also advocated an increase in taxation in order to increase public spending. (23)

Robert Wedderburn, the son of a slave, and one of the leaders of the revolutionary organisation, Society of Spencean Philanthropists, and Henry 'Orator' Hunt, accused Owen of being manipulated by the government in order to deflect working-class attention from political reform. He was also attacked by economists such as David Ricardo who said he was "completely at war with Owen" over his views on government intervention in trade and industry. (24)

A second meeting took place on 21st August, Owen rounded on all teachers of religion as having made man "a weak, imbecile animal; a furious bigot and fanatic; or a miserable hypocrite". His audience, Owen later recalled, was "thunderstruck". A few clergymen hissed but according to one newspaper, "the loudest cheers" took place when condemned the "vices of existing religious establishments". (25)

Owen's criticisms of religion caused much distress, including reformers such as William Wilberforce and William Cobbett. It also upset one of his business partners, William Allen, who was a devout Quaker. As his biographer, Leslie Stephen, has pointed out, Allen was "alarmed by Owen's avowed atheism" and tried to persuade him to introduce "biblical instruction in the New Lanark schools" and to ban "the teaching of singing, dancing, and drawing". (26)

The Father of Socialism

Over the next few years Robert Owen developed political views that has resulted in him being described as the "father of socialism". In the Report to the County of Lanark (1821) suggested that in order to avoid fluctuations in the money supply as well as the payment of unjust wages, labour notes representing hours of work might become a superior form of exchange medium. This was the first time that Owen "proclaimed at length his belief that labour was the foundation of all value, a principle of immense importance to later socialist thought". (27)

Max Beer, the author of A History of British Socialism (1919) has argued that the word "socialist" was used to describe Owen's followers: "Common to all Owenites was the criticism and disapproval of the capitalist or competitive system, as well as the sentiment that the United Kingdom was on the eve of adopting the new views. A boundless optimism prevaded the whole Owenite school, and it filled its adherents with the unshakable belief that the conversation of the nation to socialism was at hand, or but a question of a few years." (28)

Disappointed with the response he received in Britain, Owen decided in 1825 to establish a new community in America based on the socialist ideas that he had developed over the years. Owen purchased the town of Harmony in Indiana from George Rapp for £24,000. Rapp was the leader of a religious group called the Harmonists (German Lutherans) Owen called the community he established there, New Harmony. (29)

Robert Owen explained in a letter to William Allen that he was convinced that America was an excellent place to establish his socialist community: "The principle of union and co-operation for the promotion of all the virtues and for the creation of wealth is now universally admitted to be far superior to the individual selfish system and all seems prepared or are rapidly preparing to give up the latter and adopt the former. In fact the whole of this country is ready to commence a new empire upon the principle of public property and to discard private property and the uncharitable notion that man can form his own character as the foundation and root of all evil." (30)

By 1827 Owen had lost interest in his New Lanark textile mills and decided to sell the business. His four sons and one of his daughters, Jane, moved to New Harmony and made it their permanent home. Robert Dale Owen became the leader of the new community in America. Another son, William Owen, admitted that the town often attracted the wrong people. "I doubt whether those who have been comfortable and content in their old mode of life, will find an increase of enjoyment when they come here. How long it will require to accustom themselves to their new mode of living, I am unable to determine." (31)

Owen attempted to set up Owenite villages in England. Over the next twenty years he established seven communities, the largest being at Orbiston in Scotland and at East Tytherly in Hampshire. John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984) points out that "Owenism" was the main British variety of what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called utopian socialism. "The Owenites believed that society could be radically transformed by means of experimental communities, in which property was held in common, and social and economic activity was organized on a cooperative basis. This was a method of effecting social change which was radical, peaceful and immediate." (32)

George Holyoake became an Owenite Missionary and claimed that he was the most important political thinker since Thomas Paine. In his autobiography, Sixty Years of an Agitator's Life (1892) Holyoake explained why Owen was so important: "Just as Thomas Paine was the founder of political ideas among the people of England, Robert Owen was also the founder of social ideas among them. He who first conceives a new idea has merit and distinction; but he is the founder of it who puts it into the minds of men by proving its practicability. Mr. Owen did this at New Lanark, and convinced numerous persons that the improvement of society was possible by wise material means.... Owen gave social ideas form and force. His passion was the organization of labour, and to cover the land with self-supporting cities of industry, in which well-devised material condition should render ethical life possible, in which labour should be, as far as possible, done by machinery, and education, recreation, and competence should be enjoyed by all. Instead of communities working for the world, they should work for themselves, and keep in their own hands the fruit of their labour; and commerce should be an exchange of surplus wealth, and not a necessity of existence. All this Owen believed to be practicable." (33)

Henry Hetherington was another devoted follower of Robert Owen's political and religious beliefs: "I consider priestcraft and superstition the greatest obstacle to human improvement and happiness. I have ever considered that the only religion useful to man consists exclusively of the practice of morality, and in the mutual interchange of kind actions. In such a religion there is no room for priests and when I see them interfering at our births, marriages and deaths pretending to conduct us safely through this state of being to another and happier world, any disinterested person of the least shrewdness and discernment must perceive that their sole aim is to stultify the minds of the people by their incomprehensible doctrines that they may the more effectively fleece the poor deluded sheep who listen to their empty babblings and mystifications.... The scrambling, selfish system; a system by which the moral and social aspirations of the noblest human being are nullified by incessant toil and physical deprivations; by which, indeed, all men are trained to be either slaves, hypocrites or criminals. Hence my ardent attachment to the principles of that great and good man Robert Owen." (34)

William Lovett, a carpenter and John Cleave, a printer, were both followers of Robert Owen and together they formed the London Co-operative Trading Association for the purpose of "formation of a community on the principles of mutual co-operation" and to restore "the whole produce of labour to the labourer". Members resolved not to "live off the labours of others". (35)

This inspired other Owenites to establish cooperative trading stores, "some of which were established by working men to accumulate funds for starting a community, proved eventually to be viable; and the continuous history of the modern cooperative movement is usually traced from the foundation of an Owenite store in Rochdale in 1844." (36)

Grand National Trade Union

Ralph Miliband has argued that Owen's political ideas would never be successful: "His insistence upon the futility of political agitation, his belief in the need to rely upon the enlightened benevolence of the governing orders, and his advocacy of a union between rich and poor made it impossible for him to play a central part in the movement of protest which followed the end of the wars. Above all, Owen's distrust of the 'industrialised poor' and his inveterate conviction that their independent action must inevitably lead to anarchy and chaos denied him the support of those leaders of labour who... came to believe that the political organization of the people was the key to social progress." (37)

Socialists such as Owen were very disappointed by the passing of the 1832 Reform Act. Voting in the boroughs was restricted to men who occupied homes with an annual value of £10. There were also property qualifications for people living in rural areas. As a result, only one in seven adult males had the vote. Nor were the constituencies of equal size. Whereas 35 constituencies had less than 300 electors, Liverpool had a constituency of over 11,000. Owen now realised that he would have to develop more radical methods to obtain social change. (38)

Robert Owen gave his support to Michael Sadler in his attempts to reduce the hours worked by children. On 16th March 1832 Sadler introduced legislation that proposed limiting the hours of all persons under the age of 18 to ten hours a day. He argued: "The parents rouse them in the morning and receive them tired and exhausted after the day has closed; they see them droop and sicken, and, in many cases, become cripples and die, before they reach their prime; and they do all this, because they must otherwise starve. It is a mockery to contend that these parents have a choice. They choose the lesser evil, and reluctantly resign their offspring to the captivity and pollution of the mill." (39)

The vast majority of the House of Commons were opposed to Sadler's proposal. However, in April 1832 it was agreed that there should be another parliamentary enquiry into child labour. Sadler was made chairman and for the next three months a parliamentary committee, that included John Cam Hobhouse, Charles Poulett Thompson, Robert Peel, Lord Morpeth, and Thomas Fowell Buxton interviewed 89 witnesses.

On 9th July Michael Sadler discovered that at least six of these workers had been sacked for giving evidence to the parliamentary committee. Sadler announced that this victimisation meant that he could no longer ask factory workers to be interviewed. He now concentrated on interviewing doctors who had experience treating people who worked in textile factories. In the 1832 General Election, Sadler lost his seat to John Marshall, the Leeds flax-spinning magnate. (40)

Parliament did pass 1833 Factory Act, but it disappointed the reformers. As R. W. Cooke-Taylor "The working day was to start at 5.30 a.m. and cease at 8.30 p.m. A young person (aged thirteen to eighteen) might not be employed beyond any period of twelve hours, less one and a half for meals; and a child (aged nine to thirteen) beyond any period of nine hours." This was much more limited than many trade unionists had hoped. (41)

Owen was so disappointed with this legislation that in November 1833 he joined John Doherty, leader of the Lancashire cotton spinners, and John Fielden, the mill owner and MP for Todmorden, to establish the National Regeneration Society. Its main object was the eight hour day in factories. (42)

Robert Owen now came to the conclusion that the only way forward was through the trade union movement. He called for the establishment of a single body of trade unionists in Britain. In October 1833 he wrote that "national arrangements shall be formed to include all the working classes in the great organisation". (43)

The first meeting of the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union (GNCTU) took place on 13th February, 1834. Within a few weeks the organisation had gained over 1,500,000 members. James Morrison, the editor of Pioneer, the official paper of the GNCTU, wrote: "our little snowballs have all been rolled together and formed into a mighty avalanche". (44)

Owen hoped it would be possible to use the GNCTU to peacefully supplant capitalism. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) argues that once the GNCTU "had been formed, strikes broke out everywhere, making demands on its resources that it had no means of meeting and at the same time scaring the government into a belief that the revolution was at hand." The government decided to fight back and six farm labourers at Tolpuddle were charged with administering illegal oaths and sentenced to transportation. Over 100,000 people demonstrated against this verdict in London but it was unable to stop the men being sent to Australia. The decline of the GNCTU was as rapid as the growth and in August 1834 it was closed down. (45)

In 1835, Robert Owen formed the Association of All Classes and All Nations (later renamed the Rational Society). Over the next five years it started over 60 branches of self-styled "socialists" concentrated in the manufacturing districts, with perhaps 50,000 flocking to weekly lectures. The society's regular paper, New Moral World, ran for nearly eleven years (1834–45), and achieved a circulation of about 40,000 weekly at its peak. Such was his fame that in 1839 he was presented to Queen Victoria. (46)

Emma Martin

In 1839 Emma Martin she heard a lecture by Alexander Campbell, a man who had been deeply influenced by the writings of Robert Owen. Campbell was a socialist who was involved with an increasingly militant trade unionism in Scotland. In 1834 he had been imprisoned for his involvement with the unstamped press. Campbell also campaigned against the Poor Law Amendment Act (1834) and helped organise the Cotton Spinners' Union. In 1838 he was appointed by the Association of All Classes and All Nations (later renamed the Rational Society). as a "social missionary" to preach the Owenite gospel. (46a)

Emma Martin became convinced by Campbell's message and later that year Emma Martin attended the Owenite Congress held in Birmingham and was astounded to hear "so close a transcript of many of the thoughts that had passed in my mind". (46b) However, she disagreed at first with the socialists about Christianity. She challenged the socialists to public debates on the validity of Christianity. One who took part in a debate with her commented that "She is a lady of considerable talent". (46c)

Isaac Martin was opposed to her socialist and feminist political opinions and she was forced to leave the family home. All her property, by law, now belonged to her husband. Now without means of keeping herself or her daughters, she embarked on a career as a lecturer. "Emma Martin... concentrated on physiology, the condition of women and socialism. She developed her feminism and argued the case that woman's subordinate position was due to lack of education; she blamed the marriage system which made a woman an object of a commercial transaction." (46d)

Over the next few years Emma Martin became the most important Owenite orator. New Moral World reported that Emma Martin argued that if women had a good standard of education it would benefit men. "Mrs Martin lectured at our Institution yesterday afternoon, on the errors of our present Social System, particularly as respects the condition of women; after displaying the great and appalling evil of society as at present constituted, and the opposition generally made to all improvements, she dwelt upon the inefficient education of her own sex, especially in those arts and sciences would assist them in the discharge of their duties as wives and mothers, and commented upon the apathy existing among women upon this important subject." (46e)

Emma Martin would give a course of three lectures. She visited Macclesfield in January 1841: "On Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday evenings, the 17th, 18th, and 19th instant, we had a course of lectures from the talented Mrs Martin, whose powers of oratory and logical skill must convince the most scrupulous, that women is capable of being trained and educated equal with man. The order of her lectures ran thus: 1, 'Religion of the New Moral World'; 2, 'The Doctrine of Responsibility'; 3, 'The Marriage System'. It is unnecessary to say more upon these lectures, here, as the audiences were so well satisfied with the arguments adduced by the lectures, that, at the concluding lecture, they passed the following resolution: 'That it is the opinion of this meeting, that Mrs E. Martin will render the cause of human improvement a great and lasting benefit, if she will kindly condescend to have her three lectures published." (46f)

Her biographer, Barbara Taylor, argues that Emma Martin's religious beliefs gradually began to crumble. "Faced with the arguments of the freethinking Owenites - whose ideas on women's rights so strongly echoed her own - and made wretched by her personal circumstances, she felt the ground of Christian conviction begin to give way beneath her... She took the leap of faith and joined the socialists as a declared freethinker. Within a year she was one of the movement's best-known women adherents, lecturing, writing, and debating anti-socialists, particularly clerical ones, all over Britain. From having been a vigorous campaigner in Christ's cause, she became one of the church's most vociferous opponents, notorious for her knockabout style of free-thought polemic and for her hostility to conventional Christian views on women and marriage." (46g)

Emma Martin became one of Owenism's most enthusiastic orators and tractarians, covering thousands of miles and issuing tens of thousands of pamphlets. "Singing Social Hymns, attending meetings of the Socialist Ladies' Tract Committee, naming children at the conclusion of a Sunday School sermon... small wonder Emma could move so readily from Baptism to Owenism. From being an evangelical in Christ's cause, she became one of the leading evangelizers of infidel Socialism, within a milieu and style that seemed to alter very little with the transfer of allegiances." (46h)

In her lectures Emma Martin compared the various religions but believed that the ideas advocated by Robert Owen "contained all the best parts of each, and was calculated in a superior degree to satisfy, direct, and elevate the human mind. It was true it had no creed - no ceremony - except the charity she recommended could be termed so." At the end of the lecture she concluded "by inviting any lady or gentleman to come forward and object to any thing she had advanced, if they dissented from her views, saying that by these means she might be led to refute any objections which the arguments contained in her lectures had not fairly met. No one, however, came forward for that purpose." (46i)

In 1841 the Owenite annual congress Emma Martin pointed out that "she had grown up from infancy with high thoughts and strong hopes of an improvement in the condition of her sex, but that all institutions for mental improvement were confined to males, and that even the morals of the female sex were of a different stamp to those of the male. She saw no remedy for this till she saw the remedy of Socialism. When all should labour for each, and each be expected to labour for the whole, then would woman be placed in a position in which she would not sell her liberties." (46j)

Emma Martin took a keen interest in the subject of crime and punishment. In a speech in Nottingham she linked the problems in this area with Christianity: "I hardly need say the sermon was the right sort, and went to the very root of the evil, whence has originated the crimes that have rendered capital punishments apparently necessary. Kingcraft and priestcraft, and the Bible as the text book of both, were denounced as the great obstacles to the improvement of the people. Christianity was shown to be the best apology for crime, while it was the most decided opponent of every thing that could elevate, enlighten, and improve mankind. These sentiments were received with the most evident satisfaction - a proof that the people are prepared to hear the whole truth on such subjects." (46k)

Newspaper reports of Emma Martin's lectures described audiences of up to 3000, strongly divided in their views and expressing their opinions in raucous and sometimes violent forms. Emma's strident atheism was particularly provocative - so much so that even some of her fellow socialists objected. In 1842, angered by this lack of support from the movement, she and her fellow atheist George Holyoake set up the Anti-Persecution Union to defend freethinkers charged with blasphemy. Sometimes her meetings ended up with an anti-Owenite mob stoning her. (46l)

Owen Communities

Later that year Owen and the Rational Society attempted to create a new community called Queenwood on a 533-acre site designed for 700 members. "Owen's own vision of its creation as a symbol of his ideas also became steadily more grandiose and impractical. Much of the money collected for the community was spent on constructing, in 1842, an impressively large building with lavish fittings. Especially noteworthy was a model kitchen with a conveyor to carry food and dishes to and from the dining room which, its architect exulted, rivalled the amenities of any London hotel. This would have been a great achievement had Owen been a hotelier. Owen's defence was that the community was intended to be the standard for a superior socialist future where all would enjoy privileges the wealthy monopolized at present, nay even more, for all apartments were eventually to have central heating and cooling, hot and cold water, and artificial light. Its main building thus ought to be superior to any palace. By 1844, after over £40,000 had been spent, Queenwood bankrupted the society". (47)

All the socialist communities he created were unsuccessful. Ian Donnachie, the author of Robert Owen: Social Visionary (2000) has argued that this "could be put down to his failure to realise that the success of New Lanark as a dynamic capitalist enterprise under his management could hardly be replicated in multi-functional villages where the profit motive was secondary to co-operation, and to social and moral improvement." (48)

Owen himself returned to America several times over the next few years. In 1846 he helped to ease tensions between Britain and the USA over a border dispute in Oregon. After consulting with Robert Peel and Lord Aberdeen he crossed the Atlantic four times in fewer than six months in an effort to solve the problem. In June he wrote "the Oregon question was finally settled and on the principle which I recommended and the details will scarcely vary from my proposals to both governments." (49)

In February 1848, revolution broke out in Paris. Although nearly 77-years-old, he raced to the French capital in an attempt to popularize his views, placarding the walls of the city with broadsheets. He also wrote several articles which was both an appeal to the nation and an offer of his services to the provisional government. Owen praised the French people for taking such action and urged them to form a government to serve as an example to the world. (50)

In one article published in Le Populaire, he explained his achievements over the previous sixty years: "I have created children's homes and a system of education with no punishments. I have improved the conditions of workers in factories. I have revealed the science by which we may bestow on the human race a superior character, produce an abundance of wealth and procure its just and equitable distribution. I have provided the means by which an education may gradually be achieved - an education equal for all, and greatly superior to that which the most affluent have hitherto been able to procure. I have come to France, bringing these insights and experience acquired in many countries, to consolidate the victory newly won over a false and oppressive system that could never have lasted". (51)

Owen became very ill and on his deathbed a church minister asked him if he regretted wasting his life on fruitless projects: "My life was not useless; I gave important truths to the world, and it was only for want of understanding that they were disregarded. I have been ahead of my time." (52)

Robert Owen died aged 87 on 17th November, 1858.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Owen, A New View of Society (1814)

The practice of employing children in the mills, of six, seven and eight years of age, was discontinued... The children were taught reading, writing, and arithmetic, without expense to their parents. They may therefore be taught and well-trained before they engage in any regular employment.

(2) Robert Owen, Observations on the Effect of the Manufacturing System (1815)

The manufacturing system has already so far extended its influence over the British Empire, as to effect an essential change in the general character of the mass of the people. This alteration is still in rapid progress; and ere long, the comparatively happy simplicity of the agricultural peasant will be wholly lost amongst us. It is even now scarcely anywhere to be found without a mixture of those habits which are the offspring of trade, manufactures, and commerce.

The inhabitants of every country are trained and formed by its great leading existing circumstances, and the character of the lower orders in Britain is now formed chiefly by circumstances arising from trade, manufactures, and commerce; and the governing principle of trade, manufactures, and commerce is immediate pecuniary gain, to which on the great scale every other is made to give way. All are sedulously trained to buy cheap and to sell dear; and to succeed in this art, the parties must be taught to acquire strong powers of deception; and thus a spirit is generated through every class of traders, destructive of that open, honest sincerity, without which man cannot make others happy, nor enjoy happiness himself.

But the effects of this principle of gain, unrestrained, are still more lamentable on the working classes, those who are employed in the operative parts of the manufactures; for most of these branches are more or less unfavourable to the health and morals of adults. Yet parents do not hesitate to sacrifice the well-being of their children by putting them to occupations by which the constitution of their minds and bodies is rendered greatly inferior to what it might and ought to be under a system of common foresight and humanity.

In the manufacturing districts it is common for parents to send their children of both sexes at seven or eight years of age, in winter as well as summer, at six o'clock in the morning, sometimes of course in the dark, and occasionally amidst frost and snow, to enter the manufactories, which are often heated to a high temperature, and contain an atmosphere far from being the most favourable to human life, and in which all those employed in them very frequently continue until twelve o'clock at noon, when an hour is allowed for dinner, after which they return to remain, in a majority of cases, till eight o'clock at night.

(3) Robert Owen, speech in New Lanark (1st January, 1816)

When I first came to New Lanark I found the population similar to that of other manufacturing districts... there was... poverty, crime and misery... When men are in poverty they commit crimes.., instead of punishing or being angry with our fellow-men.., we ought to pity them and patiently to trace the causes... and endeavour to discover whether they may not be removed. This was the course which I adopted.

(4) On the 26th April, 1816, Robert Owen appeared before Robert Peel's House of Commons Committee.

Question: At what age to take children into your mills?

Robert Owen: At ten and upwards.

Question: Why do you not employ children at an earlier age?

Robert Owen: Because I consider it to be injurious to the children, and not beneficial to the proprietors.

Question: What reasons have you to suppose it is injurious to the children to be employed at an earlier age?

Robert Owen: Seventeen years ago, a number of individuals, with myself, purchased the New Lanark establishment from Mr. Dale. I found that there were 500 children, who had been taken from poor-houses, chiefly in Edinburgh, and those children were generally from the age of five and six, to seven to eight. The hours at that time were thirteen. Although these children were well fed their limbs were very generally deformed, their growth was stunted, and although one of the best schoolmasters was engaged to instruct these children regularly every night, in general they made very slow progress, even in learning the common alphabet. I came to the conclusion that the children were injured by being taken into the mills at this early age, and employed for so many hours; therefore, as soon as I had it in my power, I adopted regulations to put an end to a system which appeared to me to be so injurious.

Question: Do you give instruction to any part of your population?

Robert Owen: Yes. To the children from three years old upwards, and to every other part of the population that choose to receive it.

Question: If you do not employ children under ten, what would you do with them?

Robert Owen: Instruct them, and give them exercise.

Question: Would not there be a danger of their acquiring, by that time, vicious habits, for want of regular occupation.

Robert Owen: My own experiences leads me to say, that I found quite the reverse, that their habits have been good in proportion to the extent of their instruction.

(5) Robert Owen, The Life of Robert Owen (1857)

The local shops... sold goods at high prices... I arranged superior shops... to supply every article of food, clothing etc. which they required... I bought everything.., on a large scale... these goods were then supplied to the people at the cost price. The result of this change was to save them... a full twenty-five per cent.

(6) L. G. Brandon, A Survey of British History (1951)

Robert Owen, a young Welshman who in 1800 became the owner of a great cotton mill at New Lanark on Clydeside... He refused to employ any child under ten: he built good houses for his employees and schools for their children: he paid fair wages and reduced working hours... In later years Owen was to carry his ideas further, and to advocate the transfer of industry from private control to the community, thus winning the name of the "Father of Socialism".

(7) William Lovett, Life and Struggles (1876)

I entertain the highest respect for Mr. Owen's generous intentions. I was one of those who, at one time, was favourably impressed with many of Mr. Owen's views, and, more especially, with those of a community of property. This notion has a peculiar attraction for the plodding, toiling, ill-remunerated sons and daughters of labour.

(8) George Holyoake, Sixty Years of an Agitator's Life (1892)

Just as Thomas Paine was the founder of political ideas among the people of England, Robert Owen was also the founder of social ideas among them. He who first conceives a new idea has merit and distinction; but he is the founder of it who puts it into the minds of men by proving its practicability. Mr. Owen did this at New Lanark, and convinced numerous persons that the improvement of society was possible by wise material means. There were social ideas in England before the days of Owen, as there were political ideas before the days of Paine; but Owen gave social ideas form and force. His passion was the organization of labour, and to cover the land with self-supporting cities of industry, in which well-devised material condition should render ethical life possible, in which labour should be, as far as possible, done by machinery, and education, recreation, and competence should be enjoyed by all. Instead of communities working for the world, they should work for themselves, and keep in their own hands the fruit of their labour; and commerce should be an exchange of surplus wealth, and not a necessity of existence. All this Owen believed to be practicable. At New Lanark he virtually or indirectly supplied to his workpeople, with splendid munificence and practical judgment, all the conditions which gave dignity to labour. Excepting by Godin of Guise, no workmen have ever been so well treated, instructed, and cared for as at New Lanark.

Co-operation as a form of social amelioration and of profit existed in an intermittent way before New Lanark; but it was the advantages of the stores Owen incited that was the beginning of working-class co-operation. His followers intended the store to be a means of raising the industrious class, but many think of it now merely as a means of serving themselves. Still, the nobler portion are true to the earlier ideal of dividing profits in store and workshop, of rendering the members self-helping, intelligent, honest, and generous, and abating, if not superseding competition and meanness.

During all the discussions upon Mr. Owen's views, I do not remember notice being taken of Thomas Holcroft, the actor, who might have been cited as a precursor of Mr. Owen. Holcroft, mostly self-taught, familiar with hardship, vicissitude, and adventure, became an author, actor, and playwriter of distinction. He expressed views of remarkable similarity to those of Owen. Holcroft was a friend of political and moral improvement, but he wished it to be gradual and rational, because he believed no other could be effectual. He deplored all provocation and invective. All that he wished was the free and dispassionate discussion of the great principles relating to human happiness, trusting to the power of reason to make itself heard, not doubting the result. He believed the truth had a natural superiority over error, if truth could only be stated; that if once discovered it must, being left to itself, soon spread and triumph. "Men," he said, "do not become what by nature they are meant to be, but what society makes them."

Actors, apart from their profession, are mostly idealess; and the few who are capable of interest in human affairs outside the stage, are mostly so timid of their popularity that they are acquiescent, often subservient, to conventional ideas. Not so Holcroft. When it was dangerous to have independent theological or social opinions, he was as bold as Owen at a later day. He did not conceal that he was a Necessarian. He was one of a few moralists who took a chapel in Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, with a view to found an Ethical Church. One of his sayings was this: "The only enemy I encounter is error, and that with no weapon but words. My constant theme has been, 'Let error be taught, not whipped.'" Owen but put this philosophy into a system, and based public agitation upon the Holcroft principle. Owen's habit of mind and principle are there expressed. Lord Brougham, in his famous address to the Glasgow University in 1825, declared the same principle when he said no man was any more answerable for his belief than for the height of his stature or the colour of his hair. Brougham, being a life-long friend of Owen, had often heard this from him. Holcroft was born 1745, died 1809.

Robert Owen was a remarkable instance of a man at once Tory and revolutionary. He held with the government of the few, but, being a philanthropist, he meant that the government of the few should be the government of the good. It cannot be said that he, like Burke, was incapable of conceiving the existence of good social arrangements apart from kings and courts. It may be said that he never thought upon the subject. He found power in their hands, and he went to them to exercise it in the interests of his "system." He was conservative as respected their power, but conservative of nothing else. He would revolutionize both religion and society—indeed, clear the world out of the way—to make room for his "new views." He visited the chief courts of Europe. Because nothing immediately came of it, it was said he was not believed in. But there is evidence that he was believed in. He was listened to because he proposed that crowned heads should introduce his system into their states, urging that it would ensure contentment and material comfort among their people, and by giving rulers the control and patronage of social life, would secure them in their dignity.

Owen's fine temper was owing to his principle. He always thought of the unseen chain which links every man to his destiny. His fine manners were owing to natural self-possession and to his observation. When a youth behind Mr. McGuffog's counter at Stamford, the chief draper's shop in the town, he "watched the manners and studied the characters of the nobility when they were under the least restraint." It ever fell to me to entertain many eminent men, even by accident; but the first was Robert Owen. His object was to meet a professor and some young students at the London University. Two of them were Mr. Percy Greg and Mr. Michael Foster, both of whom afterwards became eminent. There were some publicists present, and Mr. W. J. Birch, author of the "Philosophy and Religion of Shakspeare," all good conversationalists. Mr. Owen was the best talker of the party. Perhaps it was that they deferred to him, or submitted to him, because of his age and public career; but he displayed more variety and vivacity than they. He spoke naturally as one who had authority. But his courtesy was never suspended by his earnestness. Owen, being a Welshman, had all the fervour and pertinacity, without the impetuosity of his race. Though he had made his own fortune by insight and energy, his fine manners came by instinct. He was successively a draper's counterman, a clerk, a manager, a trader and manufacturer; but he kept himself free from the hurry and unrest of manner which the eagerness of gain and the solicitude of loss, impart to the commercial class, and which mark the difference between their manners and those of gentlemen. There are both sorts in the House of Commons. As a rule, you know on sight the members who have made their own fortunes. If you accost them, they are apt to start as though they were arrested. An interview is an encroachment. They do not conceal that they are thinking of their time as they answer you. They look at their minutes as though they were loans, and only part with them if they are likely to bear interest. There are business men in Parliament who are born with the instinct of progress without hurry. But they are the exception.

(9) Thomas Wooler, Black Dwarf (20th August 1817)

The principal justification of Mr Owen's pretensions are that he has succeeded in changing, as he calls it, the moral habits of the persons under his employment in a manufactory at Lanark, in Scotland. For all the good he has done in that respect, he deserves the highest thanks. It is much to be wished, that all who live by the labour of the poor would pay as much attention to their wants and to their interests as Mr Owen did to those under his care at Lanark.

But it is very amusing to hear Mr Owen talk of re-moralizing the poor. Does he not think that the rich are a little more in want of re-moralizing; and particularly that class of them that has contributed to demoralize the poor, if they are demoralized, by supporting measures which have made them poor, and which now continue them poor and wretched?

Talk of the poor being demoralized! It is their would-be masters that create all the evils that afflict the poor, and all the depravity that pretended philanthropists pretend to regret.

In one point of view Mr Owen's scheme might be productive of some good. Let him abandon the labourer to his own protection; cease to oppress him, and the poor man would scorn to hold any fictitious dependence upon the rich. Give him a fair price for his labour, and do not take two-thirds of a depreciated remuneration back from him again in the shape of taxes. Lower the extravagance of the great. Tax those real luxuries, enormous fortunes obtained without merit. Reduce the herd of locusts that prey upon the honey of the hive, and think they do the bees a most essential service by robbing them. The working bee can always find a hive. Do not take from them what they can earn, to supply the wants of those who will earn nothing. Do this; and the poor will not want your splendid erections for the cultivation of misery and the subjugation of the mind.

(10) Robert Owen, The Social System (1826)

There is but one mode by which man can possess in perpetuity all the happiness which his nature is capable of enjoying, — that is by the union and co-operation of all for the benefit of each. There is but one mode by which man can possess in perpetuity all the happiness which his nature is capable of enjoying, that is by the union and co-operation of all for the benefit of each.

Union and co-operation in war obviously increase the power of the individual a thousand fold. Is there the shadow of a reason why they should not produce equal effects in peace; why the principle of co-operation should not give to men the same superior powers, and advantages, (and much greater) in the creation, preservation, distribution and enjoyment of wealth?

(11) Robert Owen, To the Population of the World (1834)

This great truth which I have now to declare to you, is, that the system on which all the nations of the world are acting is founded in gross deception, in the deepest ignorance or in a mixture of both. That, under no possible modifications of the principles on which it is based, can it ever produce good to man; but that, on the contrary, its practical results must ever be to produce evil continually' - and, consequently, that no really intelligent and honest individual can any longer support it; for, by the constitution of this system, it unavoidably encourages and upholds, as it ever has encouraged and upheld, hypocrisy and deception of every description, and discouraged and opposed truth and sincerity, whenever truth and sincerity were applied permanently to improve the condition of the human race. It encourages and upholds national vice and corruption to an unlimited extent; whilst to an equal degree it discourages national virtue and honesty.

The whole system has not one redeeming quality; its very virtues, as they are termed, are vices of great magnitude. Its charities, so called, are gross acts of injustice and deception. Its instructions are to rivet ignorance in the mind and, if possible, render it perpetual. It supports, in all manner of extravagance, idleness, presumption, and uselessness; and oppresses, in almost every mode which ingenuity can devise, industry, integrity and usefulness. It encourages superstition, bigotry and fanaticism; and discourages truth, commonsense and rationality. It generates and cultivates every inferior quality and base passion that human nature can be made to receive; and has so disordered all the human intellects, that they have become universally perplexed and confused, so that man has no just title to be called a reasonable and rational being. It generates violence, robbery and murder, and extols and rewards these vices as the highest of all virtues. Its laws are founded in gross ignorance of individual man and of human society; they are cruel and unjust in the extreme, and, united with all the superstitions in the world, are calculated only to teach men to call that which is pre-eminently true and good, false and bad; and that which is glaringly false and bad, true and good. In short, to cultivate with great care all that leads to vice and misery in the mass, and to exclude from them, with equal care, all that would direct them to true knowledge and real happiness, which alone, combined, deserve the name of virtue.

In consequence of the dire effects of this wretched system upon the whole of the human race, the population of Great Britain - the most advanced of modern nations in the acquirement of riches, power and happiness - has created and supports a theory and practice of government which is directly opposed to the real well-being and true interests of every individual member of the empire, whatever may be his station, rank or condition - whether subject or sovereign. And so enormous are the increasing errors of this system now become, that, to uphold it the government is compelled, day by day, to commit acts of the grossest cruelty and injustice, and to call such proceedings laws of justice and of Christian mercy.

Under this system, the idle, the useless and the vicious govern the population of the world; whilst the useful and the truly virtuous, as far as such a system will permit men to be virtuous, are by them degraded and oppressed.

Men of industry, and of good and virtuous habits! This is the last state to which you ought to submit; nor would I advise you to allow the ignorant, the idle, the presumptuous and the vicious, any longer to lord it over the well-being, the lives and happiness, of yourselves and families, when, by three days of such idleness as constitutes the whole of their lives, you would for ever convince each one of these mistaken individuals that you now possess the power to compel them at once to become the abject slaves, and the oppressed portion of society which they have hitherto made you.

(12) George Holyoake, Sixty Years of an Agitator's Life (1892)

Mr. Owen's sense of fame lay in his ideas. They formed a world in which he dwelt, and he thought others who saw them would be as enchanted as he was. But others did not see them, and he took no adequate means to enable them to see them. James Mill and Francis Place revised his famous "Essays on the Formation of Character," of which he sent a copy to the first Napoleon. Mr. Owen published nothing else so striking or vigorous. Yet he could speak on the platform impressively and with a dignity and force which commanded the admiration of cultivated adversaries.

Like Turner, Owen had an earlier and a later manner. His memoirs - never completed - were written apparently when Robert Fulton's death was recent. They have incident, historic surprises, and the charm of genuine autobiography; but when he wrote of his principles, he lacked altogether Cobbett's faculty of "talking with the pen," which is the source of literary engagingness. It was said of Montaigne that "his sentences were vascular and alive, and if you pricked them they bled." If you pricked Mr. Owen's, when he wrote on his "System," you lost your needle in the wool. He had the altruistic fervour as strongly as Comte, but Owen was without the artistic instinct of style, which sees an inapt word as a false tint in a picture or as an error in drawing.

His "Lectures on Marriage" he permitted to be printed in a note-taker's unskilful terms, and did not correct them, which subjected him and his adherents also to misapprehension. Everybody knows that love must always be free, and, if left to take its own course, is generally ready to accept the responsibility of its choice. People will put up with the ills they bring upon themselves, but will resent happiness proposed by others; just as a nation will be more content with the bad government of their own contriving than they will be under better laws imposed upon them by foreigners. Polygamous relations are inconsistent with delicacy or refinement. Miscellaneousness and love are incompatible terms. Love is an absolute preference. Mr. Owen regarded affection as essential to chastity; but his deprecation of priestly marriages set many against marriage itself. This was owing more to the newness of his doctrine in those days, which led to misconception on the part of some, and was wilfully perverted by others. He claimed for the poor facilities of divorce equal to those accorded to the rich. To some extent this has been conceded by law, which has tended to increase marriage by rendering it less a terror. The new liberty produced license, as all new liberty does; yet the license is not chargeable upon the liberty, nor upon those who advocated it: but upon the reaction from unlimited bondage.

Owen's philanthropy was owing to his principles. Whether wealth is acquired by chance or fraud - as a good deal of wealth is - or owing to inheritance without merit, or to greater capacity than other men have, it is alike the gift of destiny, and Mr. Owen held that those less fortunate should be assisted to improvement in their condition by the favourites of fate. Seeing that every man would be better than he is were his condition in life devised for his betterment, Owen's advice was not to hate men, but to change the system which makes them what they are or keeps them from moral advancement. For these reasons he was against all attempts at improvement by violence. Force was not reformation. In his mind reason and better social arrangements were the only remedy.

(13) Henry Hetherington, last testament (21st August 1849)

As life is uncertain, it behoves everyone to make preparations for death; I deem it therefore a duty incumbent on me, ere I quit this life, to express in writing, for the satisfaction and guidance of esteemed friends, my feelings and opinions in reference to our common principles.

In the first place, then - I calmly and deliberately declare that I do not believe in the popular notion of an Almighty, All-wise and Benevolent God - possessing intelligence, and conscious of his own operations; because these attributes involve such a mass of absurdities and contradictions, so much cruelty and injustice on His part to the poor and destitute portion of His creatures - that, in my opinion, no rational reflecting mind can, after disinterested investigation, give credence to the existence of such a Being.

Second, I believe death to be an eternal sleep - that I shall never live again in this world, or another, with a consciousness that I am the same identical person that once lived, performed the duties, and exercised the functions of a human being.

Third, I consider priestcraft and superstition the greatest obstacle to human improvement and happiness. During my life I have, to the best of my ability, sincerely and strenuously exposed and opposed them, and die with a firm conviction that Truth, Justice, and Liberty will never be permanently established on earth till every vestige of priestcraft and superstition be utterly destroyed.

Fourth, I have ever considered that the only religion useful to man consists exclusively of the practice of morality, and in the mutual interchange of kind actions. In such a religion there is no room for priests and when I see them interfering at our births, marriages and deaths pretending to conduct us safely through this state of being to another and happier world, any disinterested person of the least shrewdness and discernment must perceive that their sole aim is to stultify the minds of the people by their incomprehensible doctrines that they may the more effectively fleece the poor deluded sheep who listen to their empty babblings and mystifications.

Fifth, as I have lived so I die, a determined opponent to the nefarious and plundering system. I wish my friends, therefore, to deposit my remains in unconsecrated ground, and trust they will allow no priest, or clergyman of any denomination, to interfere in any way whatsoever at my funeral.

These are my views and principles in quitting an existence that has been chequered with the plagues and pleasures of a competitive, scrambling, selfish system; a system by which the moral and social aspirations of the noblest human being are nullified by incessant toil and physical deprivations; by which, indeed, all men are trained to be either slaves, hypocrites or criminals. Hence my ardent attachment to the principles of that great and good man Robert Owen. I quit this world with a firm conviction that his system is the only true road to human emancipation.

(14) Ralph Miliband, Journal of the History of Ideas (April 1954)

At the same time... that Owen was battling against the evils he saw around him and offering his "new view of society", he was asserting a political doctrine which ran counter to the experience of those for whom his social message had real meaning. His insistence upon the futility of political agitation, his belief in the need to rely upon the enlightened benevolence of the governing orders, and his advocacy of a union between rich and poor made it impossible for him to play a central part in the movement of protest which followed the end of the wars. Above all, Owen's distrust of the "industrialised poor" and his inveterate conviction that their independent action must inevitably lead to anarchy and chaos denied him the support of those leaders of labour who... came to believe that the political organization of the people was the key to social progress.

(15) John F. Harrison, The Common People (1984)

Robert Owen, a successful industrialist who made a fortune in cotton spinning, elaborated his plans for social reconstruction in the years after the Napoleonic Wars. His first followers were mainly radical philanthropists, but in the late 1820s Owenism attracted support among working men.

The trade union ferment of 1829-34 was dominated by Owenite theories, and for a few months in 1833-4 Owen was the acknowledged leader of the working classes. After the collapse of the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union, the Owenites developed a national organization of agents and branches which carried on propaganda and social activities until about 1845. The institutions of Owenism, however, were never as influential as its social theories. Many working-class leaders, who criticized Owen and the Owenites in the 1830s, nevertheless acknowledged their debt to Owenite socialism. Owenism provided a kind of reservoir from which different groups and individuals drew ideas and inspiration which they then applied as they chose.

Essentially Owenism was the main British variety of what Marx and Engels called utopian socialism, but which is more usefully described as communitarianism. The Owenites believed that society could be radically transformed by means of experimental communities, in which property was held in common, and social and economic activity was organized on a cooperative basis. This was a method of effecting social change which was radical, peaceful and immediate. Between 1825 and 1847 seven Owenite communities were founded in Britain, the largest being at Orbiston in Scotland and at East Tytherly, Hampshire. But attractive as the sectarian ideal of withdrawal from society in order to get on with building the `new moral world' might appear in the grim years of the 1830s and 1840s.

(16) Robert Owen, Address to the French Nation (March, 1848)

Next month I shall be 77 years of age; for sixty years I have fought this great cause despite calumnies of every kind. I have created children's homes and a system of education with no punishments. I have improved the conditions of workers in factories. I have revealed the science by which we may bestow on the human race a superior character, produce an abundance of wealth and procure its just and equitable distribution. I have provided the means by which an education may gradually be achieved - an education equal for all, and greatly superior to that which the most affluent have hitherto been able to procure. I have come to France, bringing these insights and experience acquired in many countries, to consolidate the victory newly won over a false and oppressive system that could never have lasted.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)