Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft, the eldest daughter of Edward Wollstonecraft and Elizabeth Dixon Wollstonecraft, was born in Spitalfields, London on 27th April 1759. At the time of her birth, Wollstonecraft's family was fairly prosperous: her paternal grandfather owned a successful Spitalfields silk weaving business and her mother's father was a wine merchant in Ireland. (1)

Mary did not have a happy childhood. Claire Tomalin, the author of The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (1974) has pointed out: "Mary's father was sporadically affectionate, occasionally violent, more interested in sport than work, and not to be relied on for anything, least of all for loving attention. Her mother was indolent by nature and made a darling of her first-born, Ned, two years older than Mary; by the time the little girl had learned to walk in jealous pursuit of this loving pair, a third baby was on the way. A sense of grievance may have been her most important endowment." (2)

In 1765 her grandfather died and her father, his only son, inherited a large share of the family business. He sold the business and purchased a farm at Epping. However, her father had no talent for farming. According to Mary, he was a bully, who abused his wife and children after heavy drinking sessions. She later recalled that she often had to intervene to protect her mother from her father's drunken violence (3) William Godwin claims this had a major impact on the development of her personality as Mary "was not formed to be the contented and unresisting subject of a despot". (4)

Mary had several younger brothers and sisters: Henry (1761), Eliza (1763), Everina (1765), James (1768) and Charles (1770). When she was nine years of age, the family moved to a farm in Beverley where Mary received a couple years at the local school, where she learned to read and write. It was the only formal schooling she was to receive. Ned, on the other hand, received a good education, with the hope that eventually he would become a lawyer. Mary was upset by the amount of attention Ned received and said of her mother "in comparison with her affection for him, she might be said not to love the rest of her children". (5)

Mary Wollstonecraft and Jane Arden

In 1673 Mary became friends with another fourteen-year-old, girl, Jane Arden. Her father, John Arden, was a highly educated man who gave public lectures on natural philosophy and literature. Arden also gave lessons to his daughter and her new friend. (6) "Sensitive about the failings she was beginning to perceive in her own family, and contrasting them with the dignified, sober and well-read Ardens, Mary envied Jane her entire situation and attached herself determinedly to the family." (7)

Mary and Jane had a argument and stopped seeing each other. However, they did keep in contact by letter: "Before I begin I beg pardon for the freedom of my style. If I did not love you I should not write so; I have a heart that scorns disguise, and a countenance which will not dissemble: I have formed romantic notions of friendship. I have been once disappointed - I think if I am a second time I shall only want some infidelity in a love affair, to qualify me for an old maid, as then I shall have no idea of either of them. I am a little singular in my thoughts of love and friendship; I must have the first place or none. - I own your behaviour is more according to the opinion of the world, but I would break such narrow bounds" (8)

In 1774 Edward Wollstonecraft's financial situation forced the family to move again. This time they returned to a house in Hoxton. Her brother, Ned, was being trained as a lawyer, and used to come home at weekends. Mary continued to have a bad relationship with her brother and constantly undermined her confidence. She later recalled that he took "particular pleasure in tormenting and humbling me". (9)

Fanny Blood

While in London she met Fanny Blood. "She was conducted to the door of a small house, but furnished with peculiar neatness and propriety. The first object that caught her sight, was a young woman of slender and elegant form... busily employed in feeding and managing some children, born of the same parents, but considerably her inferior in age. The impression Mary received from this spectacle was indelible; and before the interview was concluded, she had taken, in her heart, the vows of eternal friendship." (10)

Mary identified closely with her new friend: "Fanny was eighteen to Mary's sixteen, slim and pretty and set apart from the rest of her family by her manners and talents. Mary could see in her a mirror-image of herself: an eldest daughter, superior to her surroundings, often in charge of a brood of little ones, with an improvident and a drunken father and a mother charming and gentle but quite broken in spirit." (11)

After two years in London the family moved to Laugharne in Wales but Mary continued to correspond with Fanny, who had been promised in marriage to Hugh Skeys, who was living in Lisbon. Mary said in one letter that her feeling for her "resembled a passion" and was "almost (but not quite) that of an intending husband". Mary explained to Jane Arden that her relationship with Fanny was difficult to explain: "I know my resolution may appear a little extra-ordinary, but in forming it I follow the dictates of reason as well as the bent of my inclination." (12)

Mary's mother died in 1782. She now went to live with Fanny Blood and her parents at Waltham Green. Her sister Eliza, married Meredith Bishop, a boat-builder from Bermondsey. In August, 1783, after the birth of her first child, she suffered a mental breakdown and Mary was asked to look after her. When she arrived at her sister's home Mary found Eliza in a very disturbed state. Eliza explained that she had "been very ill-used by her husband".

Mary wrote to her sister, Everina, explaining that "Bishop cannot behave properly - and those who attempt to reason with him must be mad or have very little observation... My heart is almost broken with listening to Bishop while he reasons the case. I cannot insult him with advice which he would never have wanted if he was capable of attending to it." In January, 1784, the two sisters escaped from Bishop and went to live under a false name in Hackney. (13)

Richard Price

A few months later Mary Wollstonecraft opened a school in Newington Green, with her sister Eliza and a friend, Fanny Blood. Soon after arriving in the village, Mary made friends with Richard Price, a minister at the local Dissenting Chapel. Price and his friend, Joseph Priestley, were the leaders of a group of men known as Rational Dissenters. Price told her that the "love of God meant attacking injustice". (14)

Price had written several books including the very influential Review of the Principal Questions of Morals (1758) where he argued that individual conscience and reason should be used when making moral choices. Price also rejected the traditional Christian ideas of original sin and eternal punishment. As a result of these religious views, some Anglicans accused Rational Dissenters of being atheists. (15)

In January 1784, Fanny Blood travelled to Lisbon to marry Hugh Skeys. Mary missed her deeply and wrote that "without someone to love the world is a desert". She confessed that "my heart sometimes overflows with tenderness - and at other times seems quite exhausted and incapable of being warmly interested about anyone." She was attracted to John Hewlett, a young schoolmaster, and was very upset when he married another woman. (16)

Fanny Blood became seriously ill and Mary decided to visit her in Portugal. When she arrived she discovered that Fanny was nine-months pregnant. She successfully gave birth but within days both Fanny and the child were dead. Mary stayed on in Lisbon for several weeks. She and Skeys were drawn together in their grief but she had to return to her school and returned to England in February 1786. (17)

Wollstonecraft argued that friendship was more important than love: "Friendship is a serious affection; the most sublime of all affections, because it is founded on principle, and cemented by time. The very reverse may be said of love. In a great degree, love and friendship cannot subsist in the same bosom; even when inspired by different objects they weaken or destroy each other, and for the same object can only be felt in succession. The vain fears and fond jealousies, the winds which fan the flame of love, when judiciously or artfully tempered, are both incompatible with the tender confidence and sincere respect of friendship". (17a)

Although Mary was brought up as an Anglican, she soon began attending Price's Unitarian Chapel. Price held radical political views and had encountered a great deal of hostility when he supported the cause of American independence. At Price's home Mary Wollstonecraft met other leading radicals including the publisher, Joseph Johnson. He was impressed by Mary's ideas on education and commissioned her to write a book on the subject. In Thoughts on the Education of Girls, published in 1786, Mary attacked traditional teaching methods and suggested new topics that should be studied by girls. (18)

Henry Fuseli

Mary Wollstonecraft became emotionally involved with the artist Henry Fuseli. He had made a living from producing pornographic drawings and eventually gained fame for his painting The Nightmare, that showed a sleeping woman, head and shoulders dropped back over the end of her couch. She is surmounted by an incubus that peers out at the viewer. Contemporary critics were taken aback by the overt sexuality of the painting. (19)

Fuseli was forty-seven and Mary twenty-nine. He was recently married to his former model, Sophia Rawlins. Fuseli shocked his friends by constantly talking about sex. Mary later told William Godwin that she never had a physical relationship with Fuseli but she did enjoy "the endearments of personal intercourse and a reciprocation of kindness, without departing in the smallest degree from the rules she prescribed to herself". (20)

Mary fell deeply in love with Fuseli: "From him Mary learnt much about the seamy side of life... Obviously there was a time when they were in love with one another, and playing with fire; the increase of Mary's love to the point where it became torture to her is hard to explain if it remained at all times entirely platonic." (21) Mary wrote that she was enraptured by his genius, "the grandeur of his soul, that quickness of comprehension, and lovely sympathy". She proposed a platonic living arrangement with Fuseli and his wife, but Sophia rejected the idea and he broke off the relationship with Wollstonecraft. (22)

In 1788 Joseph Johnson and Thomas Christie established the Analytical Review. The journal provided a forum for radical political and religious ideas and was often highly critical of the British government. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote articles for the journal. So also did the scientist, Joseph Priestley, the philosopher, Erasmus Darwin, the poet William Cowper, the moralist William Enfield, the physician John Aikin, the author Anna Laetitia Barbauld; the Unitarian minister William Turner; the literary critic James Currie; the artist Henry Fuseli; the writer Mary Hays and the theologian Joshua Toulmin. (23)

Mary and her radical friends welcomed the French Revolution. In November, 1789, Richard Price preached a sermon praising the revolution. Price argued that British people, like the French, had the right to remove a bad king from the throne. "I see the ardour for liberty catching and spreading; a general amendment beginning in human affairs; the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priest giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience." (24)

A Vindication of the Rights of Man

Edmund Burke, was appalled by this sermon and wrote a reply called Reflections on the Revolution in France where he argued in favour of the inherited rights of the monarchy. He also attacked political activists such as Major John Cartwright, John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Thomas Walker, who had formed the Society for Constitutional Information, an organisation that promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform. (25)

Burke attacked the dissenters who were wholly "unacquainted with the world in which they are so fond of meddling, and inexperienced in all its affairs, on which they pronounce with so much confidence". He warned reformers that they were in danger of being repressed if they continued to call for changes in the system: "We are resolved to keep an established church, an established monarchy, an established aristocracy, and an established democracy; each in the degree it exists, and in no greater." (26)

Joseph Priestley was one of those attacked by Burke, pointed out: "If the principles that Mr Burke now advances (though it is by no means with perfect consistency) be admitted, mankind are always to be governed as they have been governed, without any inquiry into the nature, or origin, of their governments. The choice of the people is not to be considered, and though their happiness is awkwardly enough made by him the end of government; yet, having no choice, they are not to be the judges of what is for their good. On these principles, the church, or the state, once established, must for ever remain the same." Priestley went on to argue that these were the principles "of passive obedience and non-resistance peculiar to the Tories and the friends of arbitrary power." (27)

Mary Wollstonecraft also felt that she had to respond to Burke's attack on her friends. Joseph Johnson agreed to publish the work and decided to have the sheets printed as she wrote. According to one source when "Mary had arrived at about the middle of her work, she was seized with a temporary fit of topor and indolence, and began to repent of her undertaking." However, after a meeting with Johnson "she immediately went home; and proceeded to the end of her work, with no other interruption but what were absolutely indispensable". (28)

The pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Man not only defended her friends but also pointed out what she thought was wrong with society. This included the slave trade and way that the poor were treated. In one passage she wrote: "How many women thus waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practised as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to which it at first gave lustre." (29)

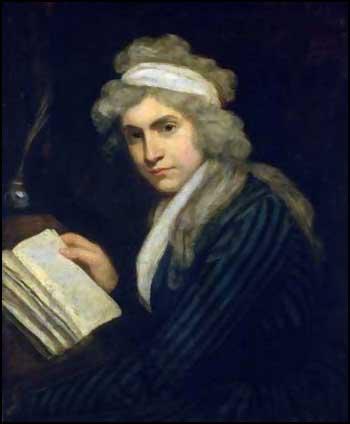

The pamphlet was so popular that Johnson was able to bring out a second edition in January, 1791. Her work was compared to that of Tom Paine, the author of Common Sense. Johnson arranged for her to meet Paine and another radical writer, William Godwin. Henry Fuseli's friend, William Roscoe, visited her and he was so impressed by her that he commissioned a portrait of her by John Williamson. "She took the trouble to have her hair powdered and curled for the occasion - a most unrevolutionary gesture - but was not very pleased with the painter's work." (30)

Vindication of the Rights of Women

In 1791 the first part of Paine's Rights of Man was published. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. "The whole system of representation is now, in this country, only a convenient handle for despotism, they need not complain, for they are as well represented as a numerous class of hard-working mechanics, who pay for the support of royalty when they can scarcely stop their children's mouths with bread." (31)

The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. Paine also argued that a reformed Parliament would reduce the possibility of going to war. "Whatever is the cause of taxes to a Nation becomes also the means of revenue to a Government. Every war terminates with an addition of taxes, and consequently with an addition of revenue; and in any event of war, in the manner they are now commenced and concluded, the power and interest of Governments are increased. War, therefore, from its productiveness, as it easily furnishes the pretence of necessity for taxes and appointments to places and offices, becomes a principal part of the system of old Governments; and to establish any mode to abolish war, however advantageous it might be to Nations, would be to take from such Government the most lucrative of its branches. The frivolous matters upon which war is made show the disposition and avidity of Governments to uphold the system of war, and betray the motives upon which they act." (32)

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy. (33)

Mary Wollstonecraft's publisher, Joseph Johnson, suggested that she should write a book about the reasons why women should be represented in Parliament. It took her six weeks to write Vindication of the Rights of Women. She told her friend, William Roscoe: "I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject. Do not suspect me of false modesty. I mean to say, that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word." (34)

In the book Wollstonecraft attacked the educational restrictions that kept women in a state of "ignorance and slavish dependence." She was especially critical of a society that encouraged women to be "docile and attentive to their looks to the exclusion of all else." Wollstonecraft described marriage as "legal prostitution" and added that women "may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent." She added: " I do not wish them (women) to have power over men; but over themselves". (35)

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. One critic described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing.

Edmund Burke continued his attack on the radicals in Britain. He described the London Corresponding Society and the Unitarian Society as "loathsome insects that might, if they were allowed, grow into giant spiders as large as oxen". King George III issued a proclamation against seditious writings and meetings, threatening serious punishments for those who refused to accept his authority.

Gilbert Imlay

In November, 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft decided to move to Paris in an effort to get away from her unhappy love affair with Henry Fuseli: "I intend no longer to struggle with a rational desire, so have determined to set out for Paris in the course of a fortnight or three weeks." She joked that "I am still a spinster on the wing... At Paris I might take a husband for the time being, and get divorced when my truant heart longed again to nestle with old friends." (36)

Mary arrived in Paris on 11th December at the start of the trial of King Louis XVI. She stayed in a small hotel and watched events from the window of her room: "Though my mind is calm, I cannot dismiss the lively images that have filled my imagination all the day... Once or twice, lifting my eyes from the paper, I have seen eyes glare through a glass-door opposite my chair, and bloody hands shook at me... I am going to bed - and, for the first time in my life, I cannot put out the candle." (37)

Also in Paris at this time was Tom Paine, William Godwin, Joel Barlow, Thomas Christie, John Hurford Stone, James Watt and Thomas Cooper. She also met the poet, Helen Maria Williams. Mary wrote to her sister, Everina, that "Miss Williams has behaved very civilly to me, and I shall visit her frequently, because I rather like her, and I meet French company at her house. Her manners are affected, yet her simple goodness of her heart continually breaks through the varnish, so that one would be more inclined, at least I should, to love than admire her." (38)

In March 1793 Mary met the writer, Gilbert Imlay, whose novel, The Emigrants, had just been published. The book appealed to Mary "because it advocated divorce and contained a portrait of a brutal and tyrannical husband". Mary was thirty-four and Imlay was five years older. "He was a handsome man, tall, thin and easy in his manner". Wollstonecraft was immediately attracted to him and described him as "a most natural, unaffected creature". (39)

William Godwin, who witnessed the relationship while he was in Paris, claims that her personality changed during this period. "Her confidence was entire; her love was unbounded. Now, for the first time in her life, she gave a loose to all the sensibilities of her nature... Her whole character seemed to change with a change of fortune. Her sorrows, the depression of her spirits, were forgotten, and she assumed all the simplicity and the vivacity of a youthful mind... She was playful, full of confidence, kindness and sympathy. Her eyes assumed new lustre, and her cheeks new colour and smothness. Her voice became cheerful; her temper overflowing with universal kindness: and that smile of bewitching tenderness from day to day illuminated her countenance, which all who knew her will so well recollect." (40)

Mary decided to live with Imlay. She wrote about those "sensations that are almost too sacred to be alluded to". The German revolutionary, George Forster in July 1793, met Mary soon after her relationship with Imlay began. "Imagine a five or eight and twenty year old brown-haired maiden, with the most candid face, and features which were once beautiful, and are still partly so, and a simple steadfast character full of spirit and enthusiasm; particularly something gentle in eye and mouth. Her whole being is wrapped up in her love of liberty. She talked much about the Revolution; her opinions were without exception strikingly accurate and to the point." (41)

Mary gave birth to a girl on 14th May 1794. She named her Fanny after her first love, Fanny Blood. She wrote to a friend about how tenderly she and Gilbert loved the new child: "Nothing could be more natural or easy than my labour. My little girl begins to suck so manfully that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the Rights of Women." (42)

In August 1794, Gilbert told Mary he had to go to London on business and he would make arrangements for her to join him in a few months. In reality he had deserted her. "When I first received your letter, putting off your return to an indefinite time, I felt so hurt that I know not what I wrote. I am now calmer, though it was not the kind of wound over which time has the quickest effect; on the contrary, the more I think, the sadder I grow... What sacrifices have you not made for a woman you did not respect! But I will not go over this ground. I want to tell you that I do not understand you." (43)

Mary returned to England in April 1795 but Imlay was unwilling to live with her and keep up appearances like a conventional husband. Instead he moved in with an actress "exposing Mary to public humiliation and forcing her to acknowledge openly the failure of her brave social experiment... it is one thing to defy the opinion of the world when you are happy, another altogether to endure it when you are miserable." Mary found it especially humiliating that his "desire for her had lasted scarcely more than a few months". (44)

One night in October 1795, she jumped off Putney Bridge into the Thames. By the time she had floated two hundred yards downstream she was seen by a couple of waterman who managed to pull her out of the river. She later wrote: "I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But a fixed determination is not to be baffled by disappointment; nor will I allow that to be a frantic attempt, which was one of the calmest acts of reason. In this respect, I am only accountable to myself. Did I care for what is termed reputation, it is by other circumstances that I should be dishonoured." (45)

William Godwin

Joseph Johnson managed to persuade her return to writing. In January 1796 he published a pamphlet entitled Letters Written During a Short Residence in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Mary was a good travel writer and provided some good portraits of the people she met in these countries. From a literary standpoint it was probably Wollstonecraft's best book. One critic commented that "If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author this appears to me to be the book". (46)

In March 1796, Mary wrote to Gilbert Imlay to tell them that she had finally accepted that their relationship was over: "I now solemnly assure you, that this is an eternal farewell... I part with you in peace". (47) Mary was now open to starting another relationship. She was visited several times by the artist, John Opie, who had recently obtained a divorce from his wife. Robert Southey also showed interest and told a friend that she was the person he liked best in the literary world. He said her face was marred only by a slight look of superiority, and that "her eyes are light brown, and, though the lid of one of them is affected by a little paralysis, they are the most meaning I ever saw". (48)

Her friend, Mary Hays, invited her to a small party where renewed her acquaintance with the philosopher, William Godwin. Although aged 40 he was still a bachelor and for most of his life he had shown little interest in women. He had recently published Enquiry into Political Justice and William Hazlitt had commented that Godwin "blazed as a sun in the firmament of reputation". (49)

The couple enjoyed going to the theatre together and going to dinner with painters, writers and politicians, where they enjoyed discussing literary and political issues. Godwin later recalled: "The partiality we conceived for each other, was in that mode, which I have always regarded as the purest and most refined of love. It grew with equal advances in the mind of each. It would have been impossible for the most minute observer to have said who was before, and who was after... I am not conscious that either party can assume to have been the agent or the patient, the toil-spreader or the prey, in the affair... I found a wounded heart... and it was my ambition to heal it." (50)

Mary Wollstonecraft married William Godwin in March, 1797 and soon afterwards, a second daughter, Mary, was born. The baby was healthy but the placenta was retained in the womb. The doctor's attempt to remove the placenta resulted in blood poisoning and Mary died on 10th September, 1797.

Primary Sources

(1) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

I do not wish them (women) to have power over men; but over themselves.

(2) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

Strengthen the female mind by enlarging it, and there will be an end to blind obedience.

(3) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone.

(4) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

But women are very differently situated with respect to each other - for they are all rivals... Is it then surprising that when the sole ambition of woman centres in beauty, and interest gives vanity additional force, perpetual rivalships should ensue? They are all running the same race, and would rise above the virtue of morals, if they did not view each other with a suspicious and even envious eye.

(5) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

There must be more equality established in society, or morality will never gain ground, and this virtuous equality will not rest firmly even when founded on a rock, if one half of mankind be chained to its bottom by fate, for they will be continually undermining it through ignorance or pride.

(6) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

Love, considered as an animal appetite, cannot long feed on itself without expiring. And this extinction, in its own flame, may be termed the violent death of love. But the wife who has thus been rendered licentious, will probably endeavour to fill the void left by the loss of her husband's attentions; for she cannot contentedly become merely an upper servant after having been treated like a goddess. She is still handsome, and, instead of transferring her fondness to her children, she only dreams of enjoying the sunshine of life. Besides, there are many husbands so devoid of sense and parental affection, that during the first effervescence of voluptuous fondness, they refuse to let their wives suckle their children. They are only to dress and live to please them: and love, even innocent love, soon sinks into lasciviousness when the exercise of a duty is sacrificed to its indulgence.

Personal attachment is a very happy foundation for friendship; yet, when even two virtuous young people marry, it would, perhaps, be happy if some circumstance checked their passion; if the recollection of some prior attachment, or disappointed affection, made it on one side, at least, rather a match founded on esteem. In that case they would look beyond the present moment, and try to render the whole of life respectable, by forming a plan to regulate a friendship which only death ought to dissolve.

Friendship is a serious affection; the most sublime of all affections, because it is founded on principle, and cemented by time. The very reverse may be said of love. In a great degree, love and friendship cannot subsist in the same bosom; even when inspired by different objects they weaken or destroy each other, and for the same object can only be felt in succession. The vain fears and fond jealousies, the winds which fan the flame of love, when judiciously or artfully tempered, are both incompatible with the tender confidence and sincere respect of friendship.

(7) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

It is time to effect a revolution in female manners - time to restore to them their lost dignity - and make them, as a part of the human species, labour by reforming themselves to reform the world. It is time to separate unchangeable morals from local manners.

(8) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

It is vain to expect virtue from women till they are in some degree independent of men; nay, it is vain to expect that strength of natural affection which would make them good wives and mothers. Whilst they are absolutely dependent on their husbands they will be cunning, mean, and selfish. The preposterous distinction of rank, which render civilization a curse, by dividing the world between voluptuous tyrants and cunning envious dependents, corrupt, almost equally, every class of people.

(9) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

How many women thus waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practised as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to which it at first gave lustre.

(10) Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

Ah! why do women condescend to receive a degree of attention and respect from strangers different from that reciprocation of civility which the dictates of humanity and the politeness of civilization authorize between man and man? And why do they not discover, when, "in the noon of beauty's power", that they are treated like queens only to be deluded by hollow respect. Confined, then, in cages like the feathered race, they have nothing to do but to plume themselves, and stalk with mock majesty from perch to perch.

(11) William Godwin, Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798)

Her (Mary Wollstonecraft) confidence was entire; her love was unbounded. Now, for the first time in her life, she gave a loose to all the sensibilities of her nature... Her whole character seemed to change with a change of fortune. Her sorrows, the depression of her spirits, were forgotten, and she assumed all the simplicity and the vivacity of a youthful mind... She was playful, full of confidence, kindness and sympathy. Her eyes assumed new lustre, and her cheeks new colour and smothness. Her voice became cheerful; her temper overflowing with universal kindness: and that smile of bewitching tenderness from day to day illuminated her countenance, which all who knew her will so well recollect.

(12) George Forster, letter to his wife (July, 1793)

Imagine a five or eight and twenty year old brown-haired maiden, with the most candid face, and features which were once beautiful, and are still partly so, and a simple steadfast character full of spirit and enthusiasm; particularly something gentle in eye and mouth. Her whole being is wrapped up in her love of liberty. She talked much about the Revolution; her fopinions were without exception strikingly accurate and to the point. The ministry at Vienna she judged with a knowledge of facts which nothing but peculiar readiness of observation could have given.

She speaks nothing but French, fluently and energetically, though not altogether correctly. But who speaks it correctly now? She has a strong thirst for instruction; says she wishes to go into the country and there study to supply the deficiencies of her education. She wishes for the company of a well-informed man, who can read and write well; and is ready to give him his board and two thousand livres a year. She is no more than a peasant girl, she said, but has a taste for learning.

(12) George Forster, letter to his wife (July, 1793)

Gracious God! It is impossible to stifle something like resentment, when I receive fresh proofs of your indifference. What I have suffered this last year, is not to be forgiven. Love is a want of my heart. I have examined myself lately with more care than formerly, and find, that to deaden is not to calm the mind - Aiming at tranquility, I have almost destroyed all the energy of my soul. .. Despair, since the birth of my child, has rendered me stupid ... the desire of regaining peace (do you understand me?) has made me forget the respect due to my own emotions - sacred emotions that are the sure harbingers of the delights I was formed to enjoy - and shall enjoy, for nothing can extinguish the heavenly spark.

(13) Mary Wollstonecraft, letter to Gilbert Imlay (19th February, 1795)

When I first received your letter, putting off your return to an indefinite time, I felt so hurt that I know not what I wrote. I am now calmer, though it was not the kind of wound over which time has the quickest effect; on the contrary, the more I think, the sadder I grow. Society fatigues me inexpressibly. So much so, that finding fault with everyone, I have only reason enough to discover that the fault is in myself. My child alone interests me, and, but for her, I should not take any pains to recover my health.

As it is, I shall wean her, and try if by that step (to which I feel a repugnance, for it is my only solace) I can get rid of my cough. Physicians talk much of the danger attending any complaint on the lungs, after a woman has suckled for some months. They lay a stress also on the necessity of keeping the mind tranquil and, my God ! how has mine been harrassed ! But whilst the caprices of other women are gratified, the wind of heaven not suffered to visit them

too rudely. I have not found a guardian angel, in heaven or on earth, to ward off sorrow or care from my bosom.What sacrifices have you not made for a woman you did not respect! But I will not go over this ground. I want to tell you that I do not understand you. You say that you have not given up all thoughts of returning here and I know that it will be necessary nay is. I cannot explain myself; but if you have not lost your memory, you will easily divine my meaning. What ! is our life then only to be made up of separations and am I only to return to a country, that has not merely lost all charms for me, but for which I feel a repugnance that almost amounts to horror, only to be left there

a prey to it !Why is it so necessary that I should return - brought up here, my girl would be freer. Indeed, expecting you to join us, I had formed some plans of usefulness that have now vanished with my hopes of happiness. In the bitterness of my heart, I could complain with reason, that I am left here dependent on a man, whose avidity to acquire a fortune has

rendered him callous to every sentiment connected with social or affectionate emotions. With a brutal insensibility, he cannot help displaying the pleasure your determination to stay gives him, in spite of the effect it is visible it has

had on me.Till I can earn money, I shall endeavour to borrow some, for I want to avoid asking him continually for the sum necessary to maintain me. Do not mistake me, I have never been refused. Yet I have gone half a dozen times to

the house to ask for it, and come away without speaking you must guess why. Besides, I wish to avoid hearing of the eternal projects to which you have sacrificed my peace not remembering but I will be silent for ever.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)