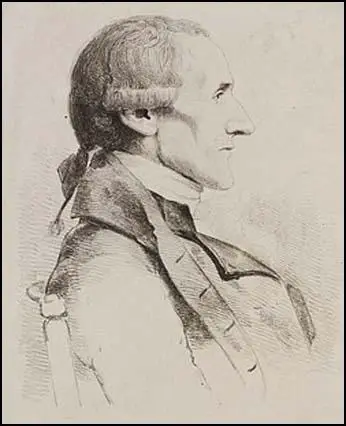

Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp, the ninth and youngest son of Thomas Sharp (1693–1758) and his wife, Judith Wheler,was born in Durham on 10th November 1735. The son of the archdeacon of Northumberland, and the grandson of John Sharp, the Archbishop of York, he decided against a career in the Church of England and instead served an apprenticeship in May 1750 to a Quaker linen draper in London.

According to his biographer, Grayson Ditchfield: "These contacts encouraged Sharp to engage in theological disputation, and he used his leisure to acquire that largely self-taught knowledge of Greek and Hebrew which formed an important basis for his career as a writer."

In 1757 he completed his apprenticeship and became a freeman of the City of London as a member of the Fishmongers' Company. The following year he obtained a post as a clerk in the Ordnance Office at the Tower of London. In 1764 he received promotion to the minuting branch as a clerk-in-ordinary.

In 1765 Sharp was living with his brother, a surgeon in Wapping. One day Jonathan Strong, a black man, arrived at the house. Strong was a slave who had been so badly beaten by his master, David Lisle, that he was close to death. Sharp took Strong to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, where he had to spend four months recovering from his injuries. Strong told Sharp how Lisle, had brought him to England from Barbados. Lisle had apparently been dissatisfied with Strong's services and after beating him with his pistol, had thrown him onto the streets.

After Jonathan Strong had regained his health, David Lisle paid two men to recapture him. When Sharp heard the news he took Lisle to court claiming that as Strong was in England he was no longer a slave. However, it was not until 1768 that the courts ruled in Strong's favour. The case received national publicity and Sharp was able to use this in his campaign against slavery.

Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997) has pointed out: "Sharp put this matter further to the test in the case of the slave Thomas Lewis, who, belonging to a West Indian planter, escaped in Chelsea. When he was recaptured, and shipped to begin the journey to Jamaica, Sharp served the captain on his boat with a writ of habeas corpus. The case came before Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, who put to the jury the question whether the master had established his claim to the slave as his property. If they decided affirmatively, he would rule whether such a property could persist in England. The jury decided that the master had not established his claim. So the main question was left unsettled. Lord Mansfield said, rather curiously, that he hoped that the question whether slaves could be forcibly shipped back to the plantations would never be discussed."

In 1769 Sharp published A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery. Soon afterwards he began to correspond and collaborate with the Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet and the Philadelphia abolitionist Benjamin Rush. He also took up the cases of other slaves such as James Somersett, and convinced the courts that "as soon as any slave sets foot upon English territory, he becomes free."

Granville Sharp developed radical political opinions about other issues as well. He argued in favour of parliamentary reform and an increase in the low wages paid to farm labourers. Sharp also supported the American colonists against the British government and as a result, had to resign from the civil service in 1776.

In April 1780 John Cartwright helped establish the Society for Constitutional Information. Granville Sharp joined the organisation. Other members included John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Gales and William Smith. It was an organisation of social reformers, many of whom were drawn from the rational dissenting community, dedicated to publishing political tracts aimed at educating fellow citizens on their lost ancient liberties. It promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform. Sharp's biographer, Grayson Ditchfield, has pointed out that "Sharp corresponded with Christopher Wyvill, John Jebb, and other reformers; he wrote strongly against triennial parliaments as an insufficient measure; and he supported the legislative independence of the Irish parliament. In the belief that the ancient constitution represented people rather than property, and as an alternative to the universal suffrage for which he was not an enthusiast, Sharp advocated a revival of the Anglo-Saxon system of frankpledge. It would involve a system of administration from tithing courts to parliament, which would secure the involvement in government, and the preservation of the rights, of an active citizenry."

In June 1786 Thomas Clarkson published Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African. As Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "A substantial book (256 pages), it traced the history of slavery to its decline in Europe and arrival in Africa, made a powerful indictment of the slave system as it operated in the West Indian colonies and attacked the slave trade supporting it. In reading it, one is struck by its raw emotion as much as by its strong reasoning." William Smith argued that the book was a turning-point for the slave trade abolition movement and made the case "unanswerably, and I should have thought, irresistibly".

During this period Sharp became interested in another issue. In 1786 Jonas Hanway established the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. This was an attempt to help black people living in London who had been victims of the slave trade. Simon Schama has argued in Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and Empire (2005) that the harsh winter of 1785-86 was one of the factors that encouraged Hanway to do something for the significant number of Africans living in poverty: "In the East End and Rotherhithe: tattered bundles of human misery, huddled in doorways, shoeless, sometimes shirtless even in the bitter cold or else covered with filthy rags."

Granville Sharp came up with the idea that this black community should be allowed to to start a colony of free slaves in Sierra Leone. The country was chosen largely on the strength of evidence from the explorer, Mungo Park and a encouraging report from the botanist, Henry Smeathman, who had recently spent three years in the area. The British government supported Sharp's plan and agreed to give £12 per African towards the cost of transport. Sharp contributed more than £1,700 to the venture. Others who invested in what became known as the Sierra Leone Company, included William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Samuel Whitbread, William Smith and Henry Thornton.

Richard S. Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has argued: "Some detractors have since denounced the Sierra Leone project as repatriation by another name. It has been seen as a high-minded yet hypocritical way of ridding the country of its rising black population... Some in Britain wanted Africans to leave because they feared they were corrupting the virtues of the country's white women, while others were tired of seeing them reduced to begging on London streets."

Granville Sharp was able to persuade a small group of London's poor to travel to Sierra Leone in 1787. As Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997), has pointed out: "A ship was charted, the sloop-of-war Nautilus was commissioned as a convoy, and on 8th April the first 290 free black men and 41 black women, with 70 white women, including 60 prostitutes from London, left for Sierra Leone under the command of Captain Thomas Boulden Thompson of the Royal Navy". When they arrived they purchased a stretch of land between the rivers Sherbo and Sierra Leone.

The settlers sheltered under old sails, donated by the navy. They named the collection of tents Granville Town after the man who had made it all possible. Granville Sharp wrote to his brother that "they have purchased twenty miles square of the finest and most beautiful country... that was ever seen... fine streams of fresh water run down the hill on each side of the new township; and in the front is a noble bay."

The reality was very different. Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has argued: "The expedition's delayed departure from England meant that it had arrived on the African coast in the midst of the malarial rainy season.... The ground was another major problem: steep, forested slopes with thin topsoil... When they managed to coax a few English vegetables out of the ground, ants promptly devoured the leaves."

Soon after arriving the colony suffered from an outbreak of malaria. In the first four months alone, 122 died. One of the white settlers wrote to Sharp: "I am very sorry indeed, to inform you, dear Sir, that... I do not think there will be one of us left at the end of a twelfth month... There is not a thing, which is put into the ground, will grow more than a foot out of it... What is more surprising, the natives die very fast; it is quite a plague seems to reign here among us."

Adam Hochschild has pointed out: "As supplies at Granville Town dwindled and crops failed, the increasingly frustrated settlers turned to the long-time mainstay of the local economy, the slave trade.... Three white doctors from Granville Town ended up at the thriving slave depot... at Bance Island." Granville Sharp was furious when he discovered what was happening and wrote to the settlers: "I could not have conceived that men who were well aware of the wickedness of slave dealing, and had themselves been suffers (or at least many of them) under the galling yoke of bondage to slave-holders... should become so basely depraved as to yield themselves instruments to promote, and extend, the same detestable oppression over their brethren."

In 1787 Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and William Dillwyn formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as John Wesley, Josiah Wedgwood, James Ramsay, and William Smith gave their support to the campaign.

Sharp was appointed as chairman. He accepted the title but never took the chair. Clarkson commented that Sharp "always seated himself at the lowest end of the room, choosing rather to serve the glorious cause in humility... than in the character of a distinguished individual." Clarkson was appointed secretary and Hoare as treasurer. At their second meeting Hoare reported subscriptions of £136.

Thomas Clarkson approached another sympathiser, Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, the MP for Hull, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it." Wilberforce's nephew, George Stephen, was surprised by this choice as he considered him a lazy man: "He worked out nothing for himself; he was destitute of system, and desultory in his habits; he depended on others for information, and he required an intellectual walking stick."

Charles Fox was unsure of Wilberforce's commitment to the anti-slavery campaign. He wrote to Thomas Walker: "There are many reasons why I am glad (Wilberforce) has undertaken it rather than I, and I think as you do, that I can be very useful in preventing him from betraying the cause, if he should be so inclined, which I own I suspect. Nothing, I think but such a disposition, or a want of judgment scarcely credible, could induce him to throw cold water upon petitions. It is from them and other demonstrations of the opinion without doors that I look for success."

In May 1788, Charles Fox precipitated the first parliamentary debate on the issue. He denounced the "disgraceful traffic" which ought not to be regulated but destroyed. He was supported by Edmund Burke who warned MPs not to let committees of the privy council do their work for them. William Dolben described shipboard horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stowed like "herrings in a barrel" and stricken with "putrid and fatal disorders" which infected crews as well. With the support of Wilberforce Samuel Whitbread, Charles Middleton and William Smith, Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. The legislation was initially rejected by the House of Lords but after William Pitt threatened to resign as prime minister, the bill passed 56 to 5 and received royal assent on 11th July.

Another debate on the slave trade took place the following year. On 12th May 1789 William Wilberforce made his first speech on the subject. Wilberforce's biographer, John Wolffe, has pointed out: "Following the publication of the privy council report on 25 April 1789, Wilberforce marked his own delayed formal entry into the parliamentary campaign on 12 May with a closely reasoned speech of three and a half hours, using its evidence to describe the effects of the trade on Africa and the appalling conditions of the middle passage. He argued that abolition would lead to an improvement in the conditions of slaves already in the West Indies, and sought to answer the economic arguments of his opponents. For him, however, the fundamental issue was one of morality and justice. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was very pleased with the speech and sent its thanks for his "unparalleled assiduity and perseverance".

The House of Commons agreed to establish a committee to look into the slave trade. Wilberforce said he did not intend to introduce new testimony as the case against the trade was already in the public record. Ellen Gibson Wilson, a leading historian on the slave trade has argued: "Everyone thought the hearing would be brief, perhaps one sitting. Instead, the slaving interests prolonged it so skilfully that when the House adjourned on 23 June, their witnesses were still testifying."

Sharp continued to refuse to accept the negative reports coming from Sierra Leone. He wrote that he had chosen "the most eligible spot for... settlement on the whole coast of Africa". With the financial support of William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and Samuel Whitbread, Sharp dispatched another shipload of black and white settlers and supplies. It was not long before Sharp began receiving reports that many of the new settlers were "wicked enough to go into the service of the slave trade".

In 1789, a Royal Navy warship making its down the coast fired a shot that set a Sierra Leone village on fire. The local chief took revenge by giving the settlers three days to depart, and then burning Granville Town to the ground. The remaining settlers were rescued by the slave traders on Bance Island. Sharp was devastated when he discovered that the last of the men he had sent to Africa were now also involved in the slave trade.

Thomas Clarkson suggested to Granville Sharp that Alexander Falconbridge should be sent to Sierra Leone. Falconbridge was appointed as a commercial agent with a £300 salary. He took a large number of gifts paid for by the Sierra Leone Company. Soon after arriving he used these gifts to persuade the local chiefs to let the settlers reoccupy their overgrown land. Falconbridge's wife, Anna Maria, was concerned about the job facing her husband. "It was surely a premature, hair-brained, and ill digested scheme, to think of sending such a number of people all at once, to a rude, barbarous and unhealthy country, before they were certain of possessing an acre of land."

They now sent John Clarkson, to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where there was a community of former American slaves who had fought for the British in the War of Independence, to recruit settlers for the abolitionist colony. With the support of Thomas Peters, the black loyalist leader, he led a fleet of fifteen vessels, carrying 1196 settlers, to Sierra Leone, which they reached on 6th March, 1792. Although sixty-five of the Nova Scotians died during the voyage, they continued to support Clarkson who they called "their Moses".

William Wilberforce believed that the support for the French Revolution by the leading members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade such as Sharp was creating difficulties for his attempts to bring an end to the slave trade in the House of Commons. He told Thomas Clarkson: "I wanted much to see you to tell you to keep clear from the subject of the French Revolution and I hope you will." Isaac Milner, after a long talk with Clarkson, commented to Wilberforce: "I wish him better health, and better notions in politics; no government can stand on such principles as he maintains. I am very sorry for it, because I see plainly advantage is taken of such cases as his, in order to represent the friends of Abolition as levellers."

On 18th April 1791 Wilberforce introduced a bill to abolish the slave trade. Wilberforce was supported by William Pitt, William Smith, Charles Fox, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, William Grenville and Henry Brougham. The opposition was led by Lord John Russell and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the MP for Liverpool. One observer commented that it was "a war of the pigmies against the giants of the House". However, on 19th April, the motion was defeated by 163 to 88.

John Clarkson became governor of the colony that was appropriately named as Freetown. However, as Hugh Brogan has argued: "It was the understanding between Clarkson and the Nova Scotians that got the colony through its very difficult first year. Clarkson's services were at first generally recognized. But great strains arose between him and the company directors, partly religious (he was not sympathetic to the insistent evangelicalism of Henry Thornton, the company chairman), partly because of the usual tension between head office and the man on the spot, and above all because Clarkson insisted on putting the views and interests of the Nova Scotians first, whereas the directors wanted the enterprise to show an early profit, so that they could compete successfully with the slave traders and bring to Africa Christianity." Clarkson was dismissed as governor on 23rd April 1793.

In March 1796, Wilberforce's proposal to abolish the slave trade was defeated in the House of Commons by only four votes. At least a dozen abolitionist MPs were out of town or at the new comic opera in London. Wilberforce wrote in his diary: "Enough at the Opera to have carried it. I am permanently hurt about the Slave Trade." Thomas Clarkson commented: "To have all our endeavours blasted by the vote of a single night is both vexatious and discouraging." It was a terrible blow to Clarkson and he decided to take a rest from campaigning against the slave trade.

Sharp and other social reformers became extremely unpopular when they supported the French Revolution. According to Grayson Ditchfield: "In common with many radicals Sharp compared the state of slavery to that of political reformers allegedly repressed by an unjust government in his own country. Like them, too, he was more concerned with constitutional issues than with the social grievances of the poor in Britain."

In 1804, Thomas Clarkson returned to his campaign against the slave trade and toured the country on horseback obtaining new evidence and maintaining support for the campaigners in Parliament. A new generation of activists such as Henry Brougham, Zachary Macaulay and James Stephen, helped to galvanize older members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

William Wilberforce introduced an abolition bill on 30th May 1804. It passed all stages in the House of Commons and on 28th June it moved to the House of Lords. The Whig leader in the Lords, Lord Grenville, said as so many "friends of abolition had already gone home" the bill would be defeated and advised Wilberforce to leave the vote to the following year. Wilberforce agreed and later commented "that in the House of Lords a bill from the House of Commons is in a destitute and orphan state, unless it has some peer to adopt and take the conduct of it".

In 1805 the bill was once again presented to the House of Commons. This time the pro-slave trade MPs were better organised and it was defeated by seven votes. Wilberforce blamed "Great canvassing of our enemies and several of our friends absent through forgetfulness, or accident, or engagements preferred from lukewarmness." Clarkson now toured the country reactivating local committees against the slave trade in an attempt to drum up the support needed to get the legislation through parliament.

In February, 1806 Lord Grenville was invited by the king to form a new Whig administration. Grenville, was a strong opponent of the slave trade. Grenville was determined to bring an end to British involvement in the trade. Thomas Clarkson sent a circular to all supporters of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade claiming that "we have rather more friends in the Cabinet than formerly" and suggested "spontaneous" lobbying of MPs.

Grenville's Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, led the campaign in the House of Commons to ban the slave trade in captured colonies. Clarkson commented that Fox was "determined upon the abolition of it (the slave trade) as the highest glory of his administration, and as the greatest earthly blessing which it was the power of the Government to bestow." This time there was little opposition and it was passed by an overwhelming 114 to 15.

In the House of Lords Lord Greenville made a passionate speech where he argued that the trade was "contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy" and criticised fellow members for "not having abolished the trade long ago". When the vote was taken the bill was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20.

In January 1807 Lord Grenville introduced a bill that would stop the trade to British colonies on grounds of "justice, humanity and sound policy". Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "Lord Grenville masterminded the victory which had eluded the abolitionist for so long... He opposed a delaying inquiry but several last-ditch petitions came from West Indian, London and Liverpool shipping and planting spokesmen.... He was determined to succeed and his canvassing of support had been meticulous." Grenville addressed the Lords for three hours on 4th February and when the vote was taken it was passed by 100 to 34. Samuel Romilly felt it to be "the most glorious event, and the happiest for mankind, that has ever taken place since human affairs have been recorded."

Under the terms of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807) British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea.

In July, 1807, members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade established the African Institution, an organization that was committed to watch over the execution of the law, seek a ban on the slave trade by foreign powers and to promote the "civilization and happiness" of Africa. The Duke of Gloucester became the first president and members of the committee included Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, Henry Brougham, James Stephen and Zachary Macaulay.

Wayne Ackerson, the author of The African Institution and the Antislavery Movement in Great Britain (2005) has argued: "The African Institution was a pivotal abolitionist and antislavery group in Britain during the early nineteenth century, and its members included royalty, prominent lawyers, Members of Parliament, and noted reformers such as William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, and Zachary Macaulay. Focusing on the spread of Western civilization to Africa, the abolition of the foreign slave trade, and improving the lives of slaves in British colonies, the group's influence extended far into Britain's diplomatic relations in addition to the government's domestic affairs. The African Institution carried the torch for antislavery reform for twenty years and paved the way for later humanitarian efforts in Great Britain."

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign such as Thomas Fowell Buxton, argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. William Wilberforce disagreed, he believed that at this time slaves were not ready to be granted their freedom. He pointed out in a pamphlet that he wrote in 1807 that: "It would be wrong to emancipate (the slaves). To grant freedom to them immediately, would be to insure not only their masters' ruin, but their own. They must (first) be trained and educated for freedom."

Sharp joined Thomas Clarkson, Thomas Fowell Buxton, William Allen, Joseph Sturge, Thomas Walker, James Cropper, Elizabeth Pease, Anne Knight, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd and Zachary Macaulay in the campaign against slavery.

Granville Sharp, who lived mainly in Garden Court, Temple. After a gradual physical and mental decline he was not to see the final abolition of slavery as he died on 6th July, 1813 and was buried in Fulham churchyard seven days later.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade (1997)

Granville Sharp acted as if the judgements of Attorney-General Yorke had no authority. He based his arguments on the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, and insisted that a master had rights in a slave only if he could prove that the captive in question had in writing willingly "bound himself, without compulsion or illegal duress". Whatever might be the custom in the colonies, in England, he argued, an African slave immediately became entitled to the King's protection.

Sharp's arguments made headway, and his opponents in the case of Jonathan Strong did not press their suit. His success, and his subsequent pamphlet, A Representation of the Injustice arid Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery in England, published in 1769, made him a natural recipient

of other complaints by blacks in England who were either kidnapped or threatened with kidnapping.

Sharp put this matter further to the test in the case of the slave Thomas Lewis, who, belonging to a West Indian planter, escaped in Chelsea. When he was recaptured, and shipped to begin the journey to Jamaica, Sharp served the captain on his boat with a writ of habeas corpus. The case came before Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, who put to the jury the question whether the master had established his claim to the slave as his property. If they decided affirmatively, he would rule whether such a property could persist in England. The jury decided that the master had not established his claim. So the main question was left unsettled. Lord Mansfield said, rather curiously, that he hoped that the question whether slaves could be forcibly shipped back to the plantations would never be discussed.

In 1772 Sharp acted similarly, as indicated above, on behalf of the slave James Somerset, who had been brought from Jamaica to England by his master, Charles Stewart of Boston, in 1769. He escaped in 1771, was recaptured, and was then put on board the Ann and Mary, whose captain was John Knowles, bound for Jamaica, where he was to be sold. On this occasion, there could be no doubt about the master's right to the slave. But Sharp succeeded in arranging the transfer of the case to the Court of King's Bench. There, after a long trial which spread over several months, in which the fundamental questions were well put by defending counsel, Lord Mansfield decided that there was no legal definition as to whether there could, or could not be, slaves in England. He was not the most convincing of friends of liberty, since he evidently wished to avoid pronouncing on the fundamental question; to begin with, he urged a settlement out of court, and even suggested that Parliament might introduce a law to secure property in slaves. When none of these things availed, after further procrastination Mansfield decided the case on the simple ground that slavery was so 'odious' that nothing could be suffered to support it even if positive law about the matter did not exist. Somerset therefore was freed. Mansfield, as he himself said in 1779, "went no further than to determine that the master had no right to compel the slave to go into a foreign country". He did not make a general declaration of slave emancipation in England. Blacks continued to be kidnapped in Britain and taken back to Jamaica or elsewhere if their masters could so arrange it.

(2) Jack Gratus, The Great White Lie (1973)

On the 22nd of May 1787 twelve men met in a room in George Yard in the City of London and came to a decision which one of them recorded in neat handwriting in a ledger. Having taken into consideration the slave trade, the note said, they resolved that it was both impolitic and unjust. Two months later they took a lease on a suite of offices at 18 Old Jewry. They called themselves the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Ten of the twelve were Quakers, members of the Society of Friends, which for a number of years had issued public statements condemning the trade on religious and humanitarian grounds. The other two men, both of them also deeply religious, had virtually committed their lives to the cause they and all the many others who were to join and follow them saw as no less than holy and sacred.

Thomas Clarkson was the prime mover of the Committee, and by unanimous decision Granville Sharp was elected its chairman. Sharp was the elder of the two. He was born in 1735, the product of an unbroken line of theologians; the Archbishop of York was his grandfather. He himself was a scholarly man who devoted his life to the pursuit of knowledge, the main source of his interest and inspiration being the Bible. He was one of fourteen children, and his father's resources were used up in the education of Granville's brothers, so he was apprenticed to a linen draper. But his intellectual curiosity found subjects for study and argument even in a drapery shop. In order to argue with a fellow apprentice who quoted from the original Greek in one of their frequent discussions about religion Granville learnt Greek in his spare time. He also learnt Hebrew so that he could debate with a Jewish apprentice on the interpretation of the Old Testament. One of his employers, he found out, had a claim to an obscure barony, and as a result of his researches Granville succeeded in sending him to the House of Lords.

Sharp eventually left the drapery business and took a position as a clerk in the Ordnance Office. In 1765 he came face to face with the slave system, not in the far-off West Indies, but in a London street. At the time he occupied apartments in the house of his brother, a surgeon in Wapping, East London. Black people in that area and in all the major ports were not uncommon; many of them were slaves who had been brought to England by their masters and had absconded rather than return to the West Indies.

One day a slave by the name of Jonathan Strong arrived at the surgeon's house. He had been badly treated by his master, a planter from Barbados, who had abandoned him when the slave's ill-health made him no longer useful. Granville Sharp became acquainted with Strong during the time his brother was treating him.

When the slave had recovered sufficiently to be of use again, his master seized him and resold him for £30. Strong sent a desperate message to Granville Sharp, who secured his immediate release. But Strong's troubles were not over. His master made another attempt to capture him, but under the threat of prosecution his would-be purchaser released him.

(3) Ellen Gibson Wilson, Thomas Clarkson (1989)

They were a faithful, hardworking band, usually meeting at least weekly at half past five or seven o'clock in the evening. They used James Phillips's premises until July when they moved into a first-floor room at 18 Old Jewry where the rent of £25 a year included the servant who lit the fire and candles for them before they arrived from their offices or dinner tables. After six months, under pressure of work, they employed John Frederick Garling to keep the minutes and send out notices, but the mounting correspondence was still dealt with by the individual members.

On 4 September 1787, the Committee formally designated Sharp as chairman although it seems to have been accepted from the start that he would hold the office. Hoare, however, signed and received all the correspondence till then, even when Sharp was present. He was chosen as a tribute to his early work and also because he was not a Quaker. He accepted the title but never took the chair. Clarkson, who eventually attended more than 700 meetings with him, said that Sharp "always seated himself at the lowest end of the room, choosing rather to serve the glorious cause in humility ... than in the character of a distinguished individual."