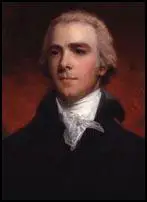

William Grenville (Lord Grenville)

William Wyndham Grenville, the fifth of seven children and the youngest son of George Grenville (1712-1770), the politician who was later to become Prime Minister (1763-65) and Elizabeth Wyndham (1720–1769), was born on 24th October 1759. According to his biographer, Peter Jupp: "Grenville was born into a family that had risen from comparative obscurity in the seventeenth century to become, partly through marriage and partly through a combination of ambition, ability, and influence, one of the richest and most powerful in Britain."

Grenville was initially educated at East Hill School in Wandsworth. Both his parents died within a year of each at the point when he started at Eton College. He also studied at Christ Church, Oxford University (1776–80) but soon after graduating his guardian, Richard Grenville-Temple, died. Grenville went to Lincoln's Inn (1780–82) but was never called to the bar and instead decided to concentrate on politics. In February 1782 he entered the House of Commons as the representative of Buckinghamshire.

Grenville supported the Whigs but in 1784 he was appointed postmaster-general by William Pitt, the new prime minister. The author of Lord Grenville 1759-1834 (1985) has pointed out: "During the next seven years Grenville... became, with Henry Dundas, Pitt's principal adviser. This was accomplished partly by his conduct in the posts that he occupied: joint paymaster-general (March 1784 to September 1789); member, and from August 1786 vice-president, of the Board of Trade (March 1784 to August 1789) ... Grenville was as fully committed as Pitt to the task of financial and commercial reconstruction following the loss of the American colonies and the removal of statutory control over Irish legislation."

In 1790 Grenville he was granted the title Lord Grenville. Now in the House of Lords, Grenville received further promotion under William Pitt and served in his government as Home Secretary (1790-91) and Foreign Secretary (1791-1801). Grenville was a strong supporter of Catholic Emancipation and in 1801 he resigned with Pitt when George III blocked proposed legislation on the subject.

In February, 1806 Lord Grenville was invited by the king to form a new Whig administration. Peter Jupp has argued: "Despite all his misgivings Grenville proved to be a very hard-working prime minister with a distinctive style of management. In keeping with the professionalism he had encouraged in the home and foreign departments, he conducted business in a methodical and businesslike manner and developed a system in which he worked closely with Fox and the other party chiefs but in about equal measure with the other departmental heads. This was supplemented with regular cabinet meetings, at least once and sometimes twice a week. The result was a form of departmental government in which Grenville tried to supervise the whole without his colleagues feeling that they were being treated like ciphers."

Grenville, was a strong opponent of the slave trade. Grenville was determined to bring an end to British involvement in the trade. Thomas Clarkson sent a circular to all supporters of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade claiming that "we have rather more friends in the Cabinet than formerly" and suggested "spontaneous" lobbying of MPs.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Grenville's Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, led the campaign in the House of Commons to ban the slave trade in captured colonies. Clarkson commented that Fox was "determined upon the abolition of it (the slave trade) as the highest glory of his administration, and as the greatest earthly blessing which it was the power of the Government to bestow." This time there was little opposition and it was passed by an overwhelming 114 to 15.

In the House of Lords Lord Grenville made a passionate speech where he argued that the trade was "contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy" and criticised fellow members for "not having abolished the trade long ago". When the vote was taken the bill was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20.

In January 1807 Lord Grenville introduced a bill that would stop the trade to British colonies on grounds of "justice, humanity and sound policy". Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "Lord Grenville masterminded the victory which had eluded the abolitionist for so long... He opposed a delaying inquiry but several last-ditch petitions came from West Indian, London and Liverpool shipping and planting spokesmen.... He was determined to succeed and his canvassing of support had been meticulous." Grenville addressed the Lords for three hours on 4th February and when the vote was taken it was passed by 100 to 34.

William Wilberforce commented: "How popular Abolition is, just now! God can turn the hearts of men". During the debate in the House of Commons the solicitor-general, Samuel Romilly, paid a fulsome tribute to Wilberforce's unremitting advocacy in Parliament. The trade was abolished by a resounding 283 to 16. According to Clarkson, it was the largest majority recorded on any issue where the House divided. Romilly felt it to be "the most glorious event, and the happiest for mankind, that has ever taken place since human affairs have been recorded."

Under the terms of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807) British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea.

Grenville now turned his attention to Catholic Emancipation. However, with the death of Charles Fox in September, 1806, Grenville government was severely weakened. When George III rejected Grenville's attempt to bring an end to Catholic disabilities in March 1807, he resigned from office. The author of Lord Grenville 1759-1834 (1985) has pointed out: "Grenville was tired and distracted by other problems besetting the government. He hoped that he could persuade the king that the bill simply replicated an Irish Act of 1793, to which the monarch had then given his assent, even though it actually went further. The king smelt a rat and refused his assent, demanding that his ministers pledge themselves not to raise the Catholic question with him again. Although Grenville and his Foxite colleagues agreed to drop the bill, they declined to take the pledge and, in the former's case, left office on 25 March 1807 with a huge sigh of relief."

Several attempts were made to persuade Grenville to return to government but he preferred to work from the backbenches. He continued to campaign against slavery and in 1815 argued against the Corn Laws. Grenville did support the introduction of the Six Acts and this led to Lord Liverpool offering his a place in his government. He refused and in 1823 a paralytic attack brought an end to his political career.

Lord Grenville died on 12th January, 1834. Peter Jupp has argued: "Grenville had a considerable and sometimes critical influence on British political history for some thirty-five years, longer in fact than each of the more famous politicians with whom he was associated - Pitt, Fox, and Grey. Part of that influence arose from measures for which he was wholly or chiefly responsible... Grenville's strengths lay in a brilliant intellect, an ability to spot the connections between different spheres of policy, and reasoned arguments in favour of specific policies."