Richard Arkwright

Richard Arkwright, the sixth of the seven children of Thomas Arkwright (1691–1753), a tailor, and his wife, Ellen Hodgkinson (1693–1778), was born in Preston on 23rd December, 1732. Richard's parents were very poor and could not afford to send him to school and instead arranged for him to be taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen. (1)

Richard became a barber's apprentice at Kirkham before moving to Bolton. He worked for Edward Pollit and in 1754 he started his own business as a wig-maker. The following year he married Patience Holt, the daughter of a schoolmaster. Their only child, Richard Arkwright, was born on 19th December 1755. After the death of his first wife he married Margaret Biggins (1723–1811) on 24th March 1761. (2)

Arkwright's work involved him travelling the country collecting people's discarded hair. In September 1767 Arkwright met John Kay, a clockmaker, from Warrington, who had been busy for some time trying to produce a new spinning-machine with another man, Thomas Highs of Leigh. Kay and Highs had run out of money and had been forced to abandon the project. Arkwright was impressed by Kay and offered to employ him to make this new machine.

Arkwright also recruited other local craftsman, including Peter Atherton, to help Kay in his experiments. According to one source: "They rented a room in a secluded teacher's house behind some gooseberry bushes, but they were so secretive that the neighbours were suspicious and accused them of sorcery, and two old women complained that the humming noises they heard at night must be the devil tuning his bagpipes." (3)

Richard Arkwright and the Spinning Frame

As the economic historian, Thomas Southcliffe Ashton, has pointed out, Arkwright did not have any great inventive ability, but "had the force of character and robust sense that are traditionally associated with his native county - with little, it may be added, of the kindliness and humour that are, in fact, the dominant traits of Lancashire people." (4)

In 1768 the team produced the Spinning-Frame and a patent for the new machine was granted in 1769. The machine involved three sets of paired rollers that turned at different speeds. While these rollers produced yarn of the correct thickness, a set of spindles twisted the fibres firmly together. The machine was able to produce a thread that was far stronger than that made by the Spinning-Jenny produced by James Hargreaves. (5)

Adam Hart-Davis has explained the way the new machine worked: "Several spinning machines were designed at about this time, but most of them tried to do the stretching and the spinning together. The problem is that the moment you start twisting the roving you lock the fibres together. Arkwright's idea was to stretch first and then twist. The roving passed from a bobbin between a pair of rollers, and then a couple of inches later between another pair that were rotating at twice the speed. The result was to stretch the roving to twice its original length. A third pair of rollers repeated the process... Two things are obvious the moment you see the wonderful beast in action. First, there are 32 bobbins along each side of each end of the water frame - 128 on the whole machine. Second, it is so automatic that even I could operate it." (6)

On 29th September 1769 Arkwright rented premises in Nottingham. However, he had difficulty finding investors in his new company. David Thornley, a merchant, of Liverpool, and John Smalley, a publican from Preston, did provide some money but he still needed more to start production. Arkwright approached a banker Ichabod Wright but he rejected the proposal because he judged that there was "little prospect of the discovery being brought into a practical state". (7)

Wright introduced Arkwright to Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need. Strutt was a manufacturer of stockings and the inventor of a machine for the machine-knitting of ribbed stockings. (8) Strutt and Need were impressed with Arkwright's new machine and agreed to form a partnership. On 19th January 1770, for £500, Need and Strutt joined the partners; Arkwright, Thornley and Smalley, were to manage the works, each having £25 a year. Financially secure, the partners commissioned Samuel Stretton to convert the premises into a horse-powered mill. (9)

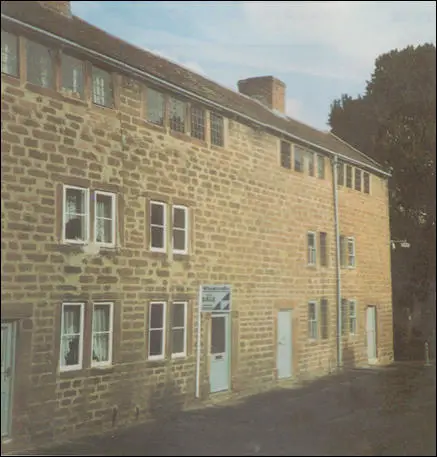

Arkwright's machine was too large to be operated by hand and so the men had to find another method of working the machine. After experimenting with horses, it was decided to employ the power of the water-wheel. In 1771 the three men set up a large factory next to the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. Arkwright later that his lawyer that Cromford had been chosen because it offered "a remarkable fine stream of water… in an area very full of inhabitants". (10) Arkwright's machine now became known as the Water-Frame. It not only "spun cotton more rapidly but produced a yarn of finer quality". (11)

Arkwright did not build the first factory in Britain. It is believed that he borrowed the idea from Matthew Boulton, who financed the Soho Manufactory in Birmingham in 1762. However, Arkwright's factory was much larger and was to inspire a generation of capitalist entrepreneurs. According to Adam Hart-Davis: "Arkwright's mill was essentially the first factory of this kind in the world. Never before had people been put to work in such a well-organized way. Never had people been told to come in at a fixed time in the morning, and work all day at a prescribed task. His factories became the model for factories all over the country and all over the world. This was the way to build a factory. And he himself usually followed the same pattern - stone buildings 30 feet wide, 100 feet long, or longer if there was room, and five, six, or seven floors high." (12)

Child Labour

In Cromford there were not enough local people to supply Arkwright with the workers he needed. After building a large number of cottages close to the factory, he imported workers from all over Derbyshire. Within a few months he was employing 600 workers. Arkwright preferred weavers with large families. While the women and children worked in his spinning-factory, the weavers worked at home turning the yarn into cloth. (13)

A local journalist wrote: "Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them. Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more." (14)

Peter Kirby, the author of Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) has argued that it was poverty that forced children into factories: "Poor families living close to a subsistence wage were often forced to draw on more diverse sources of income and had little choice over whether their chidren worked." (15) Michael Anderson has pointed out, that parents "who otherwise showed considerable affection for their children... were yet forced by large families and low wages to send their children to work as soon as possible." (16)

The youngest children in the textile factories were usually employed as scavengers and piecers. Piecers had to lean over the spinning-machine to repair the broken threads. One observer wrote: "The work of the children, in many instances, is reaching over to piece the threads that break; they have so many that they have to mind and they have only so much time to piece these threads because they have to reach while the wheel is coming out." (17)

Scavengers had to pick up the loose cotton from under the machinery. This was extremely dangerous as the children were expected to carry out the task while the machine was still working. David Rowland, worked as a scavenger in Manchester: "The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught." (18)

appeared in Trollope's Michael Armstrong (1840)

John Fielden, a factory owner, admitted that a great deal of harm was caused by the children spending the whole day on their feet: " At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock before me, I watched a child at work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it nothing short of twenty miles." (19)

Unguarded machinery was a major problem for children working in factories. One hospital reported that every year it treated nearly a thousand people for wounds and mutilations caused by machines in factories. Michael Ward, a doctor working in Manchester told a parliamentary committee: "When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children's hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way." (20)

William Blizard lectured on surgery and anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons. He was especially concerned about the impact of this work on young females: "At an early period the bones are not permanently formed, and cannot resist pressure to the same degree as at a mature age, and that is the state of young females; they are liable, particularly from the pressure of the thigh bones upon the lateral parts, to have the pelvis pressed inwards, which creates what is called distortion; and although distortion does not prevent procreation, yet it most likely will produce deadly consequences, either to the mother or the child, when the period." (21)

Edward Baines' book The History of the Cotton Manufacture (1835)

Elizabeth Bentley, who came from Leeds, was another witness that appeared before the committee. She told of how working in the card-room had seriously damaged her health: "It was so dusty, the dust got up my lungs, and the work was so hard. I got so bad in health, that when I pulled the baskets down, I pulled my bones out of their places." Bentley explained that she was now "considerably deformed". She went on to say: "I was about thirteen years old when it began coming, and it has got worse since." (22)

Samuel Smith, a doctor based in Leeds explained why working in the textile factories was bad for children's health: "Up to twelve or thirteen years of age, the bones are so soft that they will bend in any direction. The foot is formed of an arch of bones of a wedge-like shape. These arches have to sustain the whole weight of the body. I am now frequently in the habit of seeing cases in which this arch has given way. Long continued standing has also a very injurious effect upon the ankles. But the principle effects which I have seen produced in this way have been upon the knees. By long continued standing the knees become so weak that they turn inwards, producing that deformity which is called 'knock-knees' and I have sometimes seen it so striking, that the individual has actually lost twelve inches of his height by it." (23)

John Reed later recalled his life aa a child worker at Cromford Mill: "I continued to work in this factory for ten years, getting gradually advanced in wages, till I had 6s. 3d. per week; which is the highest wages I ever had. I gradually became a cripple, till at the age of nineteen I was unable to stand at the machine, and I was obliged to give it up. The total amount of my earnings was about 130 shillings, and for this sum I have been made a miserable cripple, as you see, and cast off by those who reaped the benefit of my labour, without a single penny." (24)

Business Methods

Arkwright originally produced cotton yarn for stockings, but its possibilities as warp for the loom led, in 1773, to the manufacture of calicos. Jedediah Strutt took responsibility for lobbying Parliament and eventually persuaded its members to reduce excise duties on British-made cotton goods. (25) By February 1774 the partners could, according to Elizabeth Strutt, "sell them … as fast as we could make them." (26)

As J. J. Mason has pointed out: "From the mid-1770s he sought to dominate the trade. In 1775 he successfully applied for a patent for certain instruments and machines for preparing silk, cotton, flax, and wool, for spinning. Covering a range of preparatory and spinning machines, it was an attempt to extend the length and terms of his monopoly to the whole cotton industry". (27)

When businessmen heard about Arkwright's success, they sent spies to find out what was going on in his factories. In exchange for money, some of Arkwright's employees were willing to explain how the factory was organised. Businessmen then used this information to build their own water-powered textile factories. This included spies sent from "many different countries, from Russia, Denmark, Sweden and Prussia, but the most eager of the spies were from Britain's greatest rival, France." (28)

Ralph Mather reported that Arkwright feared that Luddites would destroy his factory: "There is some fear of the mob coming to destroy the works at Cromford, but they are well prepared to receive them should they come here. All the gentlemen in this neighbourhood being determined to defend the works, which have been of such utility to this country. 5,000 or 6,000 men can be at any time assembled in less than an hour by signals agreed upon, who are determined to defend to the very last extremity, the works, by which many hundreds of their wives and children get a decent and comfortable livelihood." (29)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that in his dealings with his partners he was an "unscrupulous operator". (30) Matthew Boulton described him as a "tyrant". (31) John Smalley suggested to Jedediah Strutt that they should force Arkwright out of the company. Strutt replied. "We cannot stop his mouth or prevent his doing wrong.... but it is not in our power to remove him… for he is in possession and as much right there as we." (32)

Arkwright made further money by selling the rights to use his machines. With the 1769 patent due to expire in the summer of 1783, Arkwright faced losing his controlling hold on the cotton industry. He petitioned parliament that his patents be consolidated and the 1769 patent extended to 1789. However, as Jenny Uglow points out: "Since 1781 Lancashire cotton-spinners had spent a fortune on buildings and machines, employing around thirty thousand people - men, women, and children. They could not afford to become his licensees at prohibitive rates." (33)

In April, 1781, his competitors applied to have the decision annulled. The trial took place in June. Arkwright employed the finest lawyers and an array of witnesses. John Kay and Thomas Highs both gave evidence against Arkwright. He lost the case and a broadsheet in Manchester crowed that "the old Fox is at last caught by his over-grown beard in his own trap". (34)

Arkwright was furious with this decision and he argued that the court's decision would halt the work of other inventors. James Watt, was one of those who gave his support to Arkwright's campaign to extend his patents. Rumours circulated that he was trying to buy up the world's cotton crop. This did not happen but he did set up a company to establish cotton plantations in Africa. (35)

Despite this set-back Arkwright he remained the country's largest cotton spinner; he made huge gains in the 1770s, and even in the early 1780s his profits from the industry seem to have been at 100 per cent per annum. Thomas Carlyle described Arkwright as "a plain, almost gross, bag-cheeked, pot-bellied man, with an air of painful reflection, yet almost copious free digestion". (36)

When Samuel Need died on 14th April, 1781. Arkwright and Jedediah Strutt decided to dissolve their partnership. Strutt was disturbed by Arkwright's plans to build mills in Manchester, Winkworth, Matlock Bath and Bakewell. Strutt believed that Arkwright was expanding too fast and without the support of Need, his long-time partner, he was unwilling to take the risk of further investments. Arkwright's textile factories were very profitable. He now built factories in Lancashire, Staffordshire and Scotland. In these factories he used the new steam-engine that had recently been developed by James Watt and Matthew Boulton.

Wealth and Honours

Arkwright's biographer, J. J. Mason, claimed that: "In 1782 he bought Willersley manor and in 1789 the manor of Cromford. These acquisitions established him more firmly with the local gentry, including the Gells and Nightingales, with whom he was already connected through business.... Society sneered at his extravagance and ridiculed his gauche behaviour... but enjoyed his lavish entertainments in... Rock House, perched high and overlooking the mills and his more stately home, Willersley Castle." (37)

Arkwright was made Sheriff of Derbyshire and was knighted in 1787. King George III told Wilhelmina Murray, that he did not deal very well with the ceremony. "Tthe little great man had no idea of kneeling but crimpt himself up in a very odd posture which I suppose His Majesty took for an easy one so never took the trouble to bid him rise." (38)

Richard Arkwright's employees worked from six in the morning to seven at night. Although some of the factory owners employed children as young as five, Arkwright's policy was to wait until they reached the age of six. Two-thirds of Arkwright's 1,900 workers were children. Like most factory owners, Arkwright was unwilling to employ people over the age of forty. (39)

William Dodd carried out a study into the long-term impact on the physical health of these child workers. This included an interview with John Reed: "Here is a young man, who was evidently intended by nature for a stout-made man, crippled in the prime of life, and all his earthly prospects blasted for ever! Such a cripple I have seldom met with. He cannot stand without a stick in one hand, and leaning on a chair with the other; his legs are twisted in all manner of forms. His body, from the forehead to the knees, forms a curve, similar to the letter C. He dares not go from home, if he could; people stare at him so."

Dodd compared the life of John Reed with that of Richard Arkwright: "I have taken several walks in the neighbourhood of this beautiful and romantic place, and seen the splendid castle, and other buildings belonging to the Arkwrights, and could not avoid contrasting in my mind the present condition of this wealthy family, with the humble condition of its founder in 1768. One might expect that those who have thus risen to such wealth and eminence, would have some compassion upon their poor cripples. If it is only that they need to have them pointed out, and that their attention has hitherto not been drawn to them, I would hope and trust this case of John Reed will yet come under their notice." (40)

Arkwright had difficulty making friends and Josiah Wedgwood claimed that "he shuns all company as much as possible". Archibald Buchanan, who lived with him and found him "so intent on his schemes" they "often sat for weeks together, on opposite sides of the fire without exchanging a syllable". (41)

Richard Arkwright died aged 59 on 3rd August 1792 at his home in Cromford, after a month's illness. On 10th August, over 2,000 by two people attended his funeral. (42) The Gentleman's Magazine claimed that on his death, Arkwright was worth over £500,000 (over £200 million in today's money). (43)

Primary Sources

(1) Adam Hart-Davis, Richard Arkwright, Cotton King (10th October 1995)

About 1767, with some friends, he (Richard Arkwright) began to build a machine to spin cotton. They rented a room in a secluded teacher's house behind some gooseberry bushes, but they were so secretive that the neighbours were suspicious and accused them of sorcery, and two old women complained that the humming noises they heard at night must be the devil tuning his bagpipes...So Richard Arkwright moved over the hills to Nottingham, and designed a big machine to be driven by five or six horses, but before he even got it working he took a momentous step. He borrowed money and built a huge `"manufactory,"' to house dozens of machines and hundreds of people.

He probably borrowed the idea from Matthew Boulton, the great industrialist in Birmingham, a titan who loomed through the mists of the eighteenth century. In 1762 Boulton had gathered together a whole collection of small businesses and put them together in one complex in Soho in Birmingham; he called it the Soho Manufactory.

Arkwright went one stage further. He planned the whole thing from the ground up, and employed unskilled workers to operate the machines that he had designed and built. He leased the land in August 1771 - it cost him £14 per annum - and the mill was finished before the end of the year. The building was five floors high, and three of them still stand, although it all looks rather sorry for itself today.

What took him to the savage outback of Derbyshire? The roads were so bad that it was probably a day's journey from Nottingham, even though the distance is less than 30 miles. What he wanted was a strong and regular flow of water to power his factory. He chose Cromford because of Bonsall Brook, a good swift stream that flows out into the River Derwent half a mile downstream. And flowing into Bonsall Brook is Cromford Sough, which is essentially a drain from the lead mines in that hill.

(2) Ralph Mather described the work of the children in Richard Arkwright's factories in his book An Impartial Representation of the Case of the Poor Cotton Spinners in Lancashire (1780)

Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them.

Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more.

(3) Advert that appeared in The Derby Mercury on 20th September, 1781.

Wanted at Cromford. Forging & Filing Smiths, Joiners and Carpenters, Framework-Knitters and Weavers with large families. Likewise children of all ages may have constant employment. Boys and young men may have trades taught them, which will enable them to maintain a family in a short time.

(4) The Derby Mercury (14th November, 1777)

John Jefferies, a gunsmith of Cromford, has been committed to the House of Correction at Derby for one month; and to be kept to hard labour. John Jefferies was charged by Mr. Arkwright, Cotton Merchant, with having absented himself from his master's business without leave (being a hired servant).

(5) The Derby Mercury (22nd October, 1779)

There is some fear of the mob coming to destroy the works at Cromford, but they are well prepared to receive them should they come here. All the gentlemen in this neighbourhood being determined to defend the works, which have been of such utility to this country. 5,000 or 6,000 men can be at any time assembled in less than an hour by signals agreed upon, who are determined to defend to the very last extremity, the works, by which many hundreds of their wives and children get a decent and comfortable livelihood.

(6) James Farington, diary entry (22nd August, 1801)

In the evening I walked to Cromford, and saw the children coming from their work out of one of Mr. Arkwright's factories. These children had been at work from 6 to 7 o'clock this morning and it is now 7 in the evening.

(7) William Dodd interviewed John Reed from Arkwright's Cromford's factory in 1842.

John Reed is a sadly deformed young man living in Cromford. He tells his pitiful tale as follows: "I went to work at the cotton factory of Messrs. Arkwright at the age of nine. I was then a fine strong, healthy lad, and straight in every limb. I had at first instance 2s. per week, for seventy-two hours' work. I continued to work in this factory for ten years, getting gradually advanced in wages, till I had 6s. 3d. per week; which is the highest wages I ever had. I gradually became a cripple, till at the age of nineteen I was unable to stand at the machine, and I was obliged to give it up. The total amount of my earnings was about 130 shillings, and for this sum I have been made a miserable cripple, as you see, and cast off by those who reaped the benefit of my labour, without a single penny."

Here is a young man, who was evidently intended by nature for a stout-made man, crippled in the prime of life, and all his earthly prospects blasted for ever! Such a cripple I have seldom met with. He cannot stand without a stick in one hand, and leaning on a chair with the other; his legs are twisted in all manner of forms. His body, from the forehead to the knees, forms a curve, similar to the letter C. He dares not go from home, if he could; people stare at him so. He is now learning to make children's first shoes, and hopes ultimately to be able to get a living in this manner.

I have taken several walks in the neighbourhood of this beautiful and romantic place, and seen the splendid castle, and other buildings belonging to the Arkwrights, and could not avoid contrasting in my mind the present condition of this wealthy family, with the humble condition of its founder in 1768. One might expect that those who have thus risen to such wealth and eminence, would have some compassion upon their poor cripples. If it is only that they need to have them pointed out, and that their attention has hitherto not been drawn to them, I would hope and trust this case of John Reed will yet come under their notice.

(8) J. J. Mason, Richard Arkwright : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

The divided opinions of contemporaries, early eulogies, controversy - particularly relating to the patents - generalizations drawn from limited periods, and, not least, Arkwright's personality have compounded the problems facing his biographers.... Arkwright stood, and still stands, as the archetypal self-made man.... Still unknown are the means by which he, or Highs, stumbled upon the spinning by rollers that clearly originated with Paul and Wyatt. Research has confirmed the contemporary awareness of Arkwright's ruthless borrowing, be it of ideas or capital, from others; it has also revealed his ability, perhaps originating in the years of deference and service as a barber, to move within ever higher ranks and degrees of society...

The drama of Arkwright's life conceals the private man. His first wife died before their child was a year old, and even then he was apparently estranged from his father-in-law. He seems to have had little to do with his mother - from 1767 to 1773 she was in receipt of charity at Preston - and while at Cromford, if not earlier, lived apart from his second wife; in the 1780s there was reputedly a substantial rift with his son. A capacity for vicious quarrels with his contemporaries, whether partners or rivals, is evident, yet others, such as the gentle Jedediah Strutt - their families became friends - and Erasmus Darwin, were attracted. Arkwright was in generally good health, though he suffered from asthma all his life; his working day lasted from 5 a.m. until 9 p.m.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)