Thomas Wooler

Thomas Jonathan Wooler was born in Yorkshire in 1786. Wooler moved to London where he was apprenticed as a printer. (1) After working for the radical journal, The Reasoner, Wooler was appointed editor of The Statesman. A follower of Tom Paine, he published extracts from The Rights of Man in the journal. Wooler took a particular interest in legal matters and in 1817 he wrote and published the pamphlet An Appeal to the Citizens of London against the Packing of Special Juries. (2)

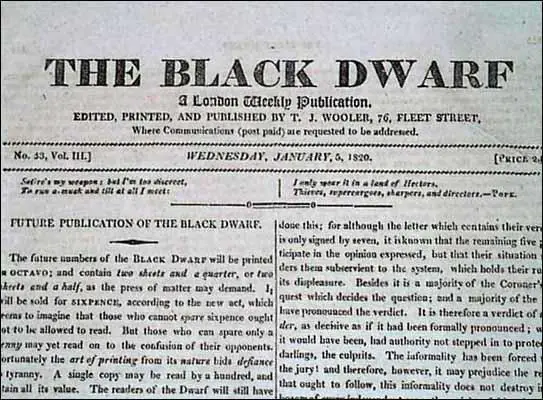

In January 1817 the British government persuaded Parliament to pass the Gagging Acts. Whereas William Cobbett responded to this act of government repression by leaving the country, Wooler was motivated to start publishing a new radical unstamped journal, the Black Dwarf. When the journal first appeared in January 1817 it was an eight page newspaper but it later became a 32 page pamphlet and cost 4d. (3)

Wooler argued that the real freedom of Englishmen lay in their power and their will to uphold their liberties, not throught the Constitution which was simply the "recorded merits of our ancestors", but by deeds. He warned "the higher orders think the best mode is to destroy the Constitution altogether and then their cause can run no further risk." (4)

This was a period of time it was possible to make a living from being a radical publisher. "The means of production of the printed page were sufficiently cheap to mean that neither capital nor advertising revenue gave much advantage; while the successful Radicalism, for the first time, a profession which could maintain its own full-time agitators." (5)

James Epstein has pointed out: "The Black Dwarf was one of the most influential radical journals of the post-war years. The journal's tone was satiric; its politics were those of radical constitutionalism. Wooler was a gifted writer known for his habit of directly typesetting his articles without first committing them to writing. Among his contributions to the journal were regular letters from the character named the Black Dwarf to various fictional correspondents." (6)

Within a few months it reached a circulation of 12,000 and received the backing of the reform movement's senior politician, Major John Cartwright. The newspaper gave its support to Cartwright's Hampden Clubs. Cartwright main objective was to unite middle class moderates with radical members of the working class. (7) It has been argued by E. P. Thompson that during this period Wooler became one of the main leaders of the reform movement. (8)

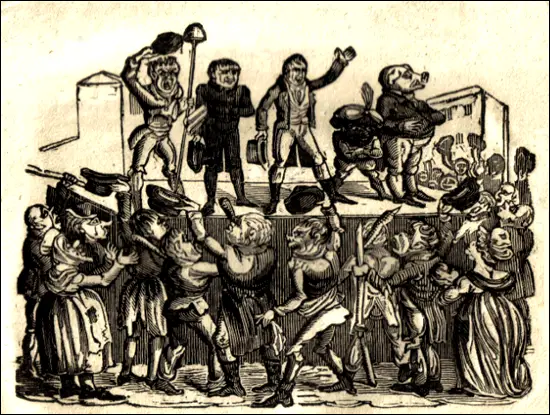

in the centre, next to him is the Black Dwarf (Thomas Wooler) and a pig dressed

as Napoleon (Thomas Spence)

Wooler compared these clubs to the work of the Quakers: "Those who condemn clubs either do not understand what they can accomplish, or they wish nothing to be done... Let us look at, and emulate the patient resolution of the Quakers. They have conquered without arms - without violence - without threats. They conquered by union." (9)

Thomas Wooler was arrested in early May 1817 and faced two trials for seditious libel for two articles published in the third and tenth numbers of the Black Dwarf. Wooler was tried at Guildhall before Justice Charles Abbott and two special juries on 5th June. The attorney-general, Samuel Shepherd, led the prosecution. Wooler defended himself brilliantly, with advice from Charles Pearson, the young City radical. He was eventually acquitted of the charges. (10)

Wooler joined forces with William Cobbett to attack Robert Owen who was attempting to create a model community in New Lanark. In August 1817, Wooler wrote: "It is very amusing to hear Mr Owen talk of re-moralizing the poor. Does he not think that the rich are a little more in want of re-moralizing; and particularly that class of them that has contributed to demoralize the poor, if they are demoralized, by supporting measures which have made them poor, and which now continue them poor and wretched? Talk of the poor being demoralized! It is their would-be masters that create all the evils that afflict the poor, and all the depravity that pretended philanthropists pretend to regret."

Wooler went on to argue that the real problem was capitalism: "Let him abandon the labourer to his own protection; cease to oppress him, and the poor man would scorn to hold any fictitious dependence upon the rich. Give him a fair price for his labour, and do not take two-thirds of a depreciated remuneration back from him again in the shape of taxes. Lower the extravagance of the great. Tax those real luxuries, enormous fortunes obtained without merit. Reduce the herd of locusts that prey upon the honey of the hive, and think they do the bees a most essential service by robbing them. The working bee can always find a hive. Do not take from them what they can earn, to supply the wants of those who will earn nothing. Do this; and the poor will not want your splendid erections for the cultivation of misery and the subjugation of the mind." (11)

Thomas Jonathan Wooler is the one with the bellows.

It is estimated that 18 people were killed and about 500 were wounded during a meeting calling for parliamentary reform on 16th August, 1819. (12) After the Peterloo Massacre, the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, sent a letter of congratulations to the Manchester magistrates for the action they had taken. He also sent a letter to Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, arguing that the government needed to take firm action. (13)

When Parliament reassembled on 23rd November, 1819, Sidmouth announced details of what later became known as the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was the "curbing radical journals and meeting as well as the danger of armed insurrection". (14)

Wooler was arrested for taking part in the campaign to elect Sir Charles Wolseley to represent Birmingham in the House of Commons. As Birmingham had not been given permission to have an election, Wooler and his fellow campaigners were charged with "forming a seditious conspiracy to elect a representative to Parliament without lawful authority". Wooler was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment. (15)

On his release from prison Wooler modified the tome of the Black Dwarf in an effort to comply with the terms of the Six Acts. As a result he lost circulation of those like Richard Carlile, the editor of The Republican, who refused to reduce his radicalism. This was a successful strategy and he was able to outsell pro-government newspapers such as The Times. (16)

To survive, Wooler had to rely on financial help from Major John Cartwright. However, on Cartwright's death on 23rd September 1824, he was forced to close the newspaper down. He wrote in the final edition that there was no longer a "public devotedly attached to the cause of parliamentary reform". Whereas in the past they had demanded reform, now they only "clamoured for bread". (17)

Wooler gradually drifted out of radical politics, and after the passing of the 1832 Reform Bill he said that "these damned Whigs have taken all the sedition out of my hands". (18)

After leaving politics he worked as a legal advocate in the police courts. In 1845 he published a legal handbook entitled Every Man his Own Attorney, intended to enable readers to avoid the expenses of a lawyer. (19)

Thomas Jonathan Wooler, who was married with one son, died on 29th October 1853.

Primary Sources

(1) Thomas Wooler, Black Dwarf (5th March 1817)

I have always thought that clubs of every description were the most important means of collecting and condensing that general, free, unpacked, and unbiased opinion of the public voice, which you say is essential... The man who would divide the public, in effect destroys the public mind.

(2) Thomas Wooler, Black Dwarf (20th August 1817)

The principal justification of Mr Owen's pretensions are that he has succeeded in changing, as he calls it, the moral habits of the persons under his employment in a manufactory at Lanark, in Scotland. For all the good he has done in that respect, he deserves the highest thanks. It is much to be wished, that all who live by the labour of the poor would pay as much attention to their wants and to their interests as Mr Owen did to those under his care at Lanark.

But it is very amusing to hear Mr Owen talk of re-moralizing the poor. Does he not think that the rich are a little more in want of re-moralizing; and particularly that class of them that has contributed to demoralize the poor, if they are demoralized, by supporting measures which have made them poor, and which now continue them poor and wretched?

Talk of the poor being demoralized! It is their would-be masters that create all the evils that afflict the poor, and all the depravity that pretended philanthropists pretend to regret.

In one point of view Mr Owen's scheme might be productive of some good. Let him abandon the labourer to his own protection; cease to oppress him, and the poor man would scorn to hold any fictitious dependence upon the rich. Give him a fair price for his labour, and do not take two-thirds of a depreciated remuneration back from him again in the shape of taxes. Lower the extravagance of the great. Tax those real luxuries, enormous fortunes obtained without merit. Reduce the herd of locusts that prey upon the honey of the hive, and think they do the bees a most essential service by robbing them. The working bee can always find a hive. Do not take from them what they can earn, to supply the wants of those who will earn nothing. Do this; and the poor will not want your splendid erections for the cultivation of misery and the subjugation of the mind.

(3) Thomas Wooler, Black Dwarf (28th July 1819)

Whatever oppression or despotism militates against, or is the ruin of the one, it must in the end be the destruction of the other; we therefore entreat them... it should be too late, to stand forward and espouse the constitutional rights of the people, by obtaining a radical reform in the system of representation, which alone can save both the trading and labouring classes from ruin.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)