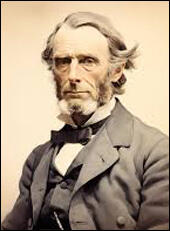

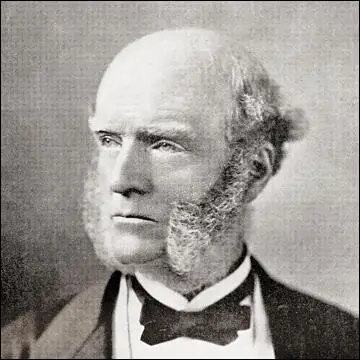

Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley, the eldest of the six surviving children of Revd Charles Kingsley (1781–1860), was born on 12 June 1819 at Holne vicarage, Devon. His father was a "wealthy man who frittered away all the money his father had made in East and West Indian trade." (1)

His mother, Mary Lucas (1787–1873), was born in Barbados, the daughter of a judge who had inherited slave-run sugar plantations. However, any prospect of substantial wealth from this source eventually passing to the Kingsley family vanished with the decline of the West Indian sugar trade and the passing of the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act. (2)

Charles was an imaginative child afflicted with a stutter which persisted into adult life. According to Leslie Stephen: "Charles was a precocious child, writing sermons and poems at the age of four. He was delicate and sensitive, and retained through life the impressions made upon him by the scenery of the fens and of Clovelly. At Clovelly he learnt to boat, to ride, and to collect shells." (3)

In 1831 he was sent to a school at Clifton, and saw the Bristol Riots of August 1831, that had been caused by the demands for parliamentary reform and the eventual passing of the 1832 Reform Act. These riots had a profound impact on Kingsley. He later wrote: "What I had seen made me for years the veriest aristocrat, full of hatred and contempt for those dangerous classes, whose existence I had for the first time discovered." (4)

His next school was Helston Grammar School, which was run by the distinguished natural scientist and priest Derwent Coleridge, who was the son of the poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In 1838, after two years at King's College, he went up to Magdalene College. It was while he was at the University of Cambridge he met Frances Eliza Greenfell, the devout daughter of Pascoe Grenfell (1761–1838) a wealthy industrialist and the member of parliament for the seat of Great Marlow, and a campaigner against the slave trade. She instantly became the focus of his life, but according to Chris Bryant, "he had to wait seven years before he could overcome both his own deep sense of sexual guilt and his future-in-laws' belief in his unworthiness." (5)

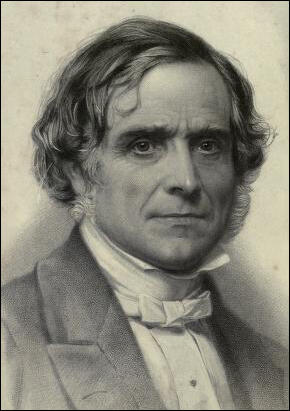

Frederick Denison Maurice

At university he read Thomas Carlyle and Frederick Denison Maurice with great interest. Leslie Stephen claims that "Though his studies seem to have been rather desultory, he was popular at college, and threw himself into every kind of sport to distract his mind. He rowed, though he did not attain to the first boat, but specially delighted in fishing expeditions into the fens and elsewhere, rode out to Sedgwick's equestrian lectures on geology, and learnt boxing under a negro prize-fighter. He was a good pedestrian, and once walked to London in a day. His distractions, intellectual, emotional, and athletic, made him regard the regular course of study as a painful drudgery." (6)

In 1842 Frances Eliza Greenfell sent him a copy of Frederick Denison Maurice's book, The Kingdom of Christ (1838), In the book Maurice argued that politics and religion are inseparable and that the church should be involved in addressing social questions. Maurice rejected individualism, with its competition and selfishness, and suggested a socialist alternative to the economic principles of laissez faire. Christian Socialists promoted the cooperative ideas of Robert Owen and suggested profit sharing as a way of improving the status of the working classes and as a means of producing a just, Christian society. (7)

After much discussion with his future wife, Kingsley resolved to become a clergyman. Six months of desperate work to make up lost time secured him a first class in classics in 1842, and he was ordained to the curacy of Eversley in Hampshire, where he immediately proved himself an energetic pastor deeply concerned with the poor. The couple married on 10th January 1844 and Fanny Kingsley gave birth to four children: Rose Georgina (b. 1845); Maurice (b.1847), Mary St. Leger (b. 1852), and Grenville Arthur (b. 1857). (8)

Rector of Eversley Church

In 1844 Kingsley was appointed rector of Eversley Church. "His predecessor had neglected the parish and much of the church itself was in disrepair, but Kingsley set out to visit as regularly as possible, especially among the poorer tenants. He started a reading class in the rectory, and opened a lending library, as well as initiating a variety of small savings schemes." (9)

Kingsley corresponded with Frederick Denison Maurice, then professor of English and history at King's College, London, on parish and theological matters, and came increasingly under his influence. In 1847 Maurice became godfather to the Kingsleys' second child, a son who was named after him. In 1848, on Maurice's recommendation, Kingsley obtained a part-time appointment as professor of English at the newly formed Queen's College for Women in London, where he gave lectures on Anglo-Saxon literature and history. (10)

In 1848 Charles Kingsley met John Ludlow who later wrote: "I found his conversation fascinating by its originality, keen observation, strong sense and imaginative power; deep feeling and broad humour succeeding each other without giving the least sense of incongruity or jar to one's feelings. His stutter, which he felt most painfully himself as a thorn in the flesh, in fact only added to a raciness in his talk as one waited for what quaint saying was going to pour out, as it always did, at full speed, the stutter once conquered." (11)

Christian Socialism

On 10th April, 1848, a group of Christians who supported Chartism held a meeting in London. People who attended the meeting included Charles Kingsley, Frederick Denison Maurice, John Ludlow and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class. (12)

Feargus O'Connor had been vicious attacks on other Chartist leaders such as William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, Bronterre O'Brien and Henry Vincent who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor became the leader of what became known as the Physical Force Chartists, Disturbed by these events members of the Christian Socialist movement volunteered to become special constables at these demonstrations. (13) John Ludlow later wrote: "The present generation has no idea of the terrorism which was at that time exercised by the Chartists." (14)

In April 1849, Kingsley wrote to his wife about the plan to publish a political newspaper. "I really cannot go home this afternoon. I have spent it with Archdeacon Hare, and Parker, starting a new periodical, a Penny People's Friend, in which Maurice, Hare, Ludlow, Mansfield, and I are going to set to work to supply the place of the defunct Saturday Magazine. I send you my first placard. Maurice is delighted with it. I cannot tell you the interest which it has excited with everyone who has seen it.... I have got already £2.10.0 towards bringing out more, and Maurice is subscription hunting for me." (14a)

The following month Charles Kingsley, Frederick Denison Maurice, Thomas Hughes, Charles Blachford Mansfield and John Ludlow began publishing a penny journal, Politics for the People, and this was considered the starting-point of the Christian Socialist movement. It was "sympathetic to the poor and based upon the acknowledgment that God rules in human society... They addressed themselves to workmen. They confessed that they were not workmen, but asked for workmen's help in bridging the gulf that divided them". (15)

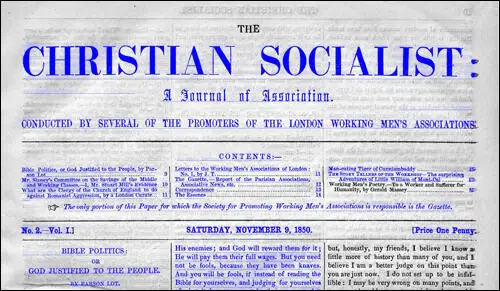

The journal was selling at about 2,000 copies an edition. (16) Kingsley wrote several articles for the journal. He took the signature ‘Parson Lot,' on account of a discussion with his friends, in which, being in a minority of one, he had said that he felt like Lot, "when he seemed as one that mocked to his sons-in-law." (17)

Kingsley made it clear he was a supporter of Chartism: "My only quarrel with the Charter is, that it does not go far enough... Instead of being a book to keep the poor in order, it (the Bible) is a book, from beginning to end, written to keep the rich in order. It is our fault. We have used the Bible as if it was a mere special constable's handbook - an opium-dose for keeping beasts of burden patient while they were being over-loaded." (18)

During the summer of 1848, Charles Mansfield, Charles Kingsley, Thomas Hughes and John Ludlow would have editorial meetings at the house of Frederick Denison Maurice. Important socialists of the day, including Robert Owen, the owner of the New Lanark Mills and Thomas Cooper, one of the leaders of the Chartist movement, sometimes took part in these discussions. (18a)

Politics for the People was an expensive journal to produce and by July 1848, after seventeen editions, the decision was taken to stop publication. Kingsley continued to write and published the pamphlet, Cheap Clothes and Nasty in 1850, and a good many contributions to the Christian Socialist, which appeared from 2nd November, 1850 to 28th June 1851. It promoted the Christian view of a socialist society. Ludlow as the editor began to diffuse the principles of co-operation by the practical application of Christianity to the purposes of trade and industry. (19)

Charles Kingsley - Novelist

Charles Kingsley's political writing concerned the authorities and although clearly a reformer rather than a revolutionary, he was briefly banned from preaching in the diocese of London. Kingsley now turned to writing novels. His first novel, Yeast: A Problem, responding to the ferment of the times, attacked celibacy, bad landlords, poor sanitation, and drew on his experience of rural poverty. "The book claims to avoid taking sides, but preaches that art is a mere self-indulgence when political action (reformist, not revolutionary) is needed." (20) It began to appear serially in Fraser's Magazine in July 1848, though it was brought to a hurried conclusion as the publisher, John William Parker, became alarmed by its radical tendency. (21)

In 1849 Charles Kingsley wrote to John Ludlow about his financial problems: "Can you as a lawyer, as well as a friend, tell me of any means of borrowing £500 for, say, five years, at reasonable interest. By that time either my books may be selling well, or my house may have stopped falling about my ears, or - or God may think we have suffered enough. My father would, but cannot help me, and therefore I dare not ask him: and as for certain rich connections of mine, I would die sooner than ask them, who tried to prevent my marriage because forsooth I was poor." (21a)

Charles Blachford Mansfield suggested lending Kingsley £140 which was all he had, and promising the balance of the £500 in the near future. Ludlow, however, knowing Kingsley's pride, drew up a document in which the creditor appeared as H. N. Turnstiles. "Eventually," wrote Ludlow, "Mrs Kingsley twigged the trick, and there was a grand scene (of gratitude) though I am not sure that Kingsley quite relished my having been the means of humbugging him." (21b)

Kingsley's next novel, Alton Locke (1850), is the story of a young tailor-boy who has instincts and aspirations beyond the normal expectations of his working-class background. (22) During his research he interviewed a tailor called Robert Crowe. He later wrote: "The Rev. Charles Kingsley, while engaged collecting material for his great work, Alton Locke, a work which has unquestionably done more to expose the pernicious nature of the sweating system than all other agencies put together, was informed that I, having worked in some of the sweating cribs of London, might furnish him with useful information on the subject, and sent me an invitation, which I was not slow to avail myself of. Of my impressions of the man, I can only say that nothing struck me so forcibly as the ready power with which he was gifted of making one feel at home in his presence. He had a manly, open countenance, the genuine English contour of features, a winning smile that perpetually played over his face, and above all, brilliant eyes that never seemed to rest, deep set beneath heavy brows." (22a)

He is intensely patriotic and has ambitions to be a poet. Locke becomes an active Chartist and eventually a Christian. Locke was partly modelled on his Chartist friend Thomas Cooper. The novel was harshly reviewed, though Thomas Carlyle liked it - "perhaps because the sympathetic portrait of the radical bookseller Sandy Mackaye was clearly modelled on himself." (23)

Kingsley followed this with the historical novel, Hypatia (1853). Based on the real-life story of Hypatia, a philosophy teacher in 5th century Alexandria, who was murdered by a group of fanatical Christians because they disapproved of her political and religious ideas. Hypatia has a strong anti-Catholic tone which reflects Kingsley's own dislike of priests and monks. Kingsley disliked priestly celibacy, and makes it clear in the novel that, in his view, it damages those who practise it. Kingsley's portrayal of a fractious and corrupt early Church is intended to reflect the 19th-century Catholic church. (24)

Kingsley's greatest popular success, the historical novel Westward Ho! (1855), was originally planned as a patriotic anti-Catholic tale about the defeat of the Spanish Armada which he hoped would strike a sympathetic note amid contemporary anxieties about by the restoration of the papal hierarchy in England in 1850 and the aggressive anti-English posturing of Emperor Napoleon III . By the time the novel was finished patriotic feeling had been redirected, as England was fighting Russia in the Crimean War, of which Kingsley was an enthusiastic supporter. His pamphlet Brave Words for Brave Soldiers and Sailors (1855) was published the same month as Westward Ho! and distributed among the troops at Sevastopol. (25)

Death of Charles Blachford Mansfield

Kinsley's friend, Charles Blachford Mansfield, returned to England in the spring of 1853, resumed his chemical studies, and began a work on the constitution of salts, based on the lectures delivered two years previously at the Royal Institution. This work, the Theory of Salts: A Treatise on the Constitution of Bipolar Chemical Compounds, his most important contribution to theoretical chemistry, he finished in 1855, and placed in a publisher's hands. (25a)

Mansfield had meanwhile been invited to send specimens of benzol to the Paris Exhibition. In 1855 he hired rooms in St. John's Wood and engaged an assistant and began the laborious process of preparing his samples. "The pair worked long hours during a cold, snowy February, watching over the hot, fume-laden apparatus, often exhausted but buoyed up by anticipation of success at the Exhibition." (25b)

On 17th February 1855, the naphtha boiled over and caught light with the risk of an explosion at any moment. Mansfield seized the burning still in his arms, intending to carry it into the street, but the door jammed, imprisoning him in the room. By the time he managed to push it out of the window both he and his assistant were badly burned. They scrambled out of the window and dropped to the snow-covered pavement. Both men rolled in the snow to smother the flames. They were taken to Middlesex Hospital but Mansfield lingered for nine agonizing days, his friends taking it in turns to sit by his bedside. (25c)

Charles Blachford Mansfield was buried in Weybridge churchyard. His tragic death, with so many of his talents unfulfilled, affected his friends emotionally for several years to come. Even in death his private life continued to embarrass them, for Mansfield left his fortune to a former lover, a Mrs Burrows, née Gardiner, even though she had subsequently married another man; she declined the bequest. (25d)

Charles Kingsley was too distressed by Mansfield's death to attend his funeral. He wrote to John Ludlow: "To him and to Frank Penrose what do I not owe. They were the only two heroic souls I met during those dark Cambridge years. They alone kept me from sinking into the mire and drowning like a dog. And now one is gone and I shall cling all the more to the other." (25e)

The Water Babies

In 1857 Kingsley published Two Years Ago, a novel about how poor sanitary conditions and had been influenced by his reading about the Crimean War. Leslie Stephen argues that; "The novel is much weaker than its predecessors, and shows clearly that if his desire for social reform was not lessened, he had no longer so strong a sense that the times were out of joint. His health and prospects had improved, a result which he naturally attributed to a general improvement of the world." (26)

Kingsley's most famous book, The Water Babies was serialized by Macmillan's Magazine in 1862 and published as a book in 1863. The book, written for his youngest son, tells the story of Tom, a young chimney-sweep, who runs away from his brutal employer. In his flight he falls into a river and is transformed into a water baby. Thereafter, in the river and in the seas, he meets all sorts of creatures and learns a series of moral lessons. (27)

Last Years

Kingsley's direct involvement with Christian Socialism gradually slackened, and he played little part in the movement's most enduring achievement, the Working Men's College. In 1860, Kingsley succeeded Sir James Stephen as regius professor of modern history at Cambridge University, then a part-time appointment. Some people objected because he was a writer of historical novels rather than a serious historian. His inaugural lecture, "The limits of exact science applied to history", was a conspicuous success, and in subsequent lectures he was able to hold steady audiences of 100 or more undergraduates, far more than his predecessors had managed. (28)

In 1865 Charles Kingsley came into conflict with some Christian Socialists over the case of John Edward Eyre, the British Governor of Jamaica. Eyre had suppressed the Morant Bay Rebellion. Up to 439 black people were killed in the reprisals, some 600 flogged, and about 1000 houses burnt down. John Ludlow and Thomas Hughes. helped form the Jamaica Committee in criticism of Eyre's excessive violence, while Charles Kingsley, Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin defended the actions of Eyre. Ludlow saw Kingsley's views as tantamount to a vicious racism and resolved to sever connections with him. (29)

In 1869 Kingsley resigned his professorship at University of Cambridge, stating that his brains as well as his purse rendered the step necessary. His health was also causing him problems. At the end of the year he sailed to the West Indies on the invitation of his friend Arthur Hamilton-Gordon, then governor of Trinidad. His At Last a graphic description of his travels, appeared in 1870. The later part of his life his interest in natural history determined a large part of his energy. At the beginning of 1874 Kingsley sailed for America, and gave some lectures but he had a severe attack of pleurisy while in San Francisco. After his return in August 1874 he continued to suffer from ill-health. (30)

Charles Kingsley died on 23rd January 1875. He was buried at Eversley on 28th January.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Kingsley, Cheap Clothes and Nasty (1850)

You are always calling out for facts, and have a firm belief in salvation by statistics. Listen to a few. The Metropolitan Commissioner of the Morning Chronicle called two meetings of the Working Tailors, one in Shadwell, and the other at the Hanover Square Rooms, in order to ascertain their condition from their own lips. Both meetings were crowded. At the Hanover Square Rooms there were more than one thousand men; they were altogether unanimous in their descriptions of the misery and slavery which they endured. It appears that there are two distinct tailor trades the 'honourable' trade, now almost confined to the West End, and rapidly dying out there, and the 'dishonourable' trade of the show shops and slop shops - the plate glass palaces, where gents - and, alas! those who would be indignant at that name - buy their cheap-and-nasty clothes. The two names are the tailors' own slang; slang is true and expressive enough, though, now and then. The honourable shops in the West End number only sixty; the dishonourable, four hundred and more; while at the East End the dishonourable trade has it all its own way. The honourable part of the trade is declining at the rate of one hundred and fifty journeymen per year; the dishonourable increasing at such a rate that, in twenty years, it will have absorbed the whole tailoring trade, which employs upwards of twenty one thousand journeymen. At the honourable shops, the work is done, as it was universally thirty years ago, on the premises and at good wages. In the dishonourable trade, the work is taken home by the men, to be done at the very lowest possible prices, which decrease year by year, almost month by month. At the honourable shops, from 36s. to 24s . is paid for a piece of work for which the dishonourable shop pays from 22s. to 9s. But not to the workmen; happy is he if he really gets two-thirds, or half of that. For at the honourable shops, the master deals directly with his workmen; while at the dishonourable ones, the greater part of the work, if not the whole, is let out to contractors, or middle men - "sweaters" , as their victims significantly call them - who, in their turn, let it out again, sometimes to the workmen, sometimes to fresh middlemen; so that out of the price paid for labour on each article, not only the workmen, but the sweater, and perhaps the sweater's sweater, and a third, and a fourth, and a fifth, have to draw their profit. And when the labour price has been already beaten down to the lowest possible, how much remains for the workmen after all these deductions, let the poor fellows themselves say!

(2) John Ludlow, The Autobiography of a Christian Socialist (1981)

I found his conversation fascinating by its originality, keen observation, strong sense and imaginative power; deep feeling and broad humour succeeding each other without giving the least sense of incongruity or jar to one's feelings. His stutter, which he felt most painfully himself as a thorn in the flesh, in fact only added to a raciness in his talk as one waited for what quaint saying was going to pour out, as it always did, at full speed, the stutter once conquered.