Robert Crowe

Robert Crowe, the son of James and Mary Crowe, was born in Dublin in 1823. He was baptised on 5th August at St Andrew's, Dublin. (1)

Robert's family suffered from extreme poverty. "First, from infancy up, it has been my lot to be surrounded by poverty, no silver spoon being in my mouth when I came into the world. Second, my education was rather, limited, being continued to the national school, and costing only one penny weekly. Attendance at school terminated in my fourteenth year, and about eighteen months of that time, employed as monitor over minor classes, and thus deprived of obtaining a fair amount of instruction, but earning enough to pay for my clothing." (2)

In 1837, at the age of 14, Crowe moved to London and was apprenticed as a tailor to his elder brother. (3) However, his brother, although "one of the best coatmakers in London", lived a dual life: "One half hard work night and day, when occasion offered; the other half, drinking his earnings, and his wife's as well, for I never remember him to have spent one hour on the board that his wife was not by his side. She was remarkably gifted as a sewer. Poor fellow, he seemed to have no control over his appetite. Four of five pounds would slip through his fingers in one night, and so for the coming week we were put to the severest straights to live." (4)

In 1840 Crowe left the employment of his brother and joined what became known as the "sweatshop system". This was when a "disreputable tailor, the owner of a 'plate glass palace' in the West End, instead of having his work done on the premises, sent it out to a series of 'sweaters' or middlemen whose employees worked in freezing attics on starvation wages." (5) The 1841 Census suggests he was married and had a 9 month son. (6)

Robert Crowe and the Temperance Society

Crowe later admitted that "with all its repulsive features, I became more proficient in six months than I had been during the three years of my apprenticeship." In 1842 joined the local branch of the Temperance Society. (7) This involved making a pledge to abstain from all alcohol for life but also a promise not to provide it to others. "In 1843 I commenced to advocate the cause publicly, but I was not slow to discover my deficiency as a speaker. I realised there was something needed, so I adopted the following novel expedient. I selected a retired, secluded spot (Soho Square), and every night, after 11 p.m., and continuing for about three months, I made the railings and trees my imaginary audience and soon learned to shudder at the echo of my voice." (8)

Daniel O'Connell

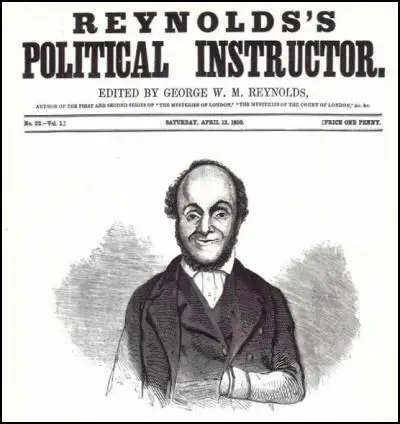

Eventually, Robert Crowe became an excellent orator. He used his skills to support various causes. Crowe became a great supporter of Daniel O'Connell and the Catholic Association campaigned for the repeal of the Act of Union, the end of the Irish tithe system, universal suffrage and a secret ballot for parliamentary elections. Although O'Connell rejected the use of violence he constantly warned the British government that if reform did not take place, the Irish masses would start listening to the "counsels of violent men". (9)

Crowe also supported O'Connell in his campaign against the Corn Laws that had caused serious distress in Ireland. Crowe joined the Anti-Corn League and attended meetings addressed by O'Connell. "An amusing incident occurred in one of those meetings, which in this connection deserves a place as illustrating the ready wit which Daniel O'Connell was gifted. The government employed a well-known stenographer named Hughes to attend these meetings and make correct reports of all speeches for future use. When O'Connell arouse to address meetings and make correct reports of all speeches for future use. When O'Connell arose to address the meeting, he turned to the direction where Mr Hughes was sitting, and shouted in the rich Irish brogue for which he was distinguished: 'Mr Hughes, are you ready to proceed?' Mr Hughes answered: 'I am, Mr O'Connell.' Then O'Connell commenced one of his most remarkable speeches, which lasted over two hours. (10)

At the age of 22 Robert Crowe attempted to organise tailors in London union and was prominent in the failed strike of tailors which took place in 1845. (11) He also met Charles Kingsley, the Christian Socialist, who was interested in writing about the sweatshop system. "The Rev. Charles Kingsley, while engaged collecting material for his great work, Alton Locke, a work which has unquestionably done more to expose the pernicious nature of the sweating system than all other agencies put together, was informed that I, having worked in some of the sweating cribs of London, might furnish him with useful information on the subject, and sent me an invitation, which I was not slow to avail myself of. Of my impressions of the man, I can only say that nothing struck me so forcibly as the ready power with which he was gifted of making one feel at home in his presence. He had a manly, open countenance, the genuine English contour of features, a winning smile that perpetually played over his face, and above all, brilliant eyes that never seemed to rest, deep set beneath heavy brows." (12)

Chartism

Another Irishman who influenced Robert Crowe was Feargus O'Connor. He became one of the leaders of the Chartist movement. The group drew up a list of six political demands. "(i) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime. (ii) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (iii) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (iv) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (v) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (vi) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period." (13)

A fellow Chartist, R. G. Gammage, explained why O'Connor was such a popular leader: "That O'Connor had a desire to make the people happier, we never in our lives disputed. He would have devoted any amount of work for that purpose; but there was only one condition on which he would consent to serve the people - the condition was, that he should be their master; and in order to become so, he stopped to flatter their most unworthy prejudices, and while telling them that they ought to depend upon his judgment, he at the same time assured them that it was not he who had given them knowledge, but that on the contrary, it was they who had conferred on him what knowledge he possessed." (14)

In his autobiography, Reminiscences of an Octogenarian (1902) Crowe explained why he spent all his free time at political meetings: "Before I reached my nineteenth year (1843) my spare time was divided between three public movements under Father Mathew, the repeal movement under Daniel O'Connell and the Chartist or English movement under Feargus O'Connor. In the bewildering whirl of excitement in which I lived during these years, I seemed almost wholly to forget myself. Night brought with it long journeys to meetings and late hours, though the day brought back the monotony of the sweater's den." (15)

Feargus O'Connor was critical of leaders such as William Lovett and Henry Hetherington who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor argued that the concessions the chartists demanded would not be conceded without a fight, so there had to be a fight. (16)

Feargus O'Connor, editor of The Northern Star, organized a National Petition that demanded parliamentary reform. At the meeting held at Kennington Common on 10th April 1848, O'Connor told the crowd that the petition contained 5,706,000 signatures. However, when it was examined by MPs it contained only 1,975,496 names and many of these, such as, those of well known opponents of parliamentary reform, Queen Victoria, Sir Robert Peel and the Duke of Wellington, were clear forgeries. (17)

Robert Crowe took part in the march. "Such was the condition when we marched over the bridges, eight abreast, on our way to Kennington Common, but no sooner did the procession pass over than the police and soldiery took possession of the bridges, and for nearly three hours we were held as prisoners…. At length the order was revoked, and the crowd was permitted to pass, and all went off quietly." (18)

The Times reported that around 50,000 people took part in the Chartist demonstration. (19) The government became concerned about the support that the Chartist movement was achieving and decided to pass new legislation against the freedom to protest. Parliament passed the Treason and Felony Act. It was a far reaching measure that redefined and extended the offence of treason, including a new treasonable offence of "open and advised speaking". (20)

Robert Crowe reacted to the rejection of the Chartist Petition by joining what became known as the Physical Force Chartists. One of the leaders of this group was William Cuffay. A police spy reported that at a meeting Cuffay gave instructions on how to make cartridges and bullets. "He also said that Ginger Beer bottles filled full of nails and ragged pieces of iron were good things for wives to throw out of the windows while the men were down in the streets fighting the police." Soon afterwards Cuffay was arrested and charged with sedition. (21)

Robert Crowe became an active member of the Irish Democratic Confederation of London - a strongly militant group that had Feargus O'Connor as president. The objectives of this Confederation included the repeal of the Union between Great Britian and Ireland and the establishment of a representative parliament. Bezer had lectured on the Irish question as well as on Chartist themes at various venues throughout the previous twelve months, including Cartwright's Coffee House in Cripplegate and the Star Coffee House Redcross Street in Golden Lane. (22)

The police began arresting leaders of the Physical Force Chartists. This was followed by other activists. This included Robert Crowe and his friend John James Bezer. (23) "Then came the second batch, consisting of thirty-two, of whom I had the honour to be one… The six weeks of our detention in Newgate prior to trial hung heavy on our hands, enlivened only by the occasional glance at the notorious William Calcraft, England's public executioner, and Chaplain Davis, the alleged 'man of God.' We used to see them while they were engaged in inspecting the gallows and conferring on the preliminaries of an execution to take place in front of the jail on the following morning." (24)

Robert Crowe and John James Bezer went on trial in September 1848. Crowe later recalled what happened: "Another gala day in the Old Bailey, when the political prisoners are placed in a row in front of the dock to receive sentence; again the court is crowded with a fashionable throng, and at the opportune time the Attorney-General rises, his pale face suffused with a cold, sardonic, sickly sneer and conjures his lordship to "pass a heavy sentence3 on the prisoner Crowe, because of the dangerously seductive and poetic character of his eloquence and its influenced on the minds of his uneducated hearers." (25)

According to The Leicestershire Mercury "The jury returned a verdict of guilty; and the other defendants who had been convicted to receive sentence. Mr Baron Platt in passing sentence, addressed them at some length upon their conduct, and told them as the sentence passed upon them at a previous session did not appear to have deterred them, it was clear an increase of severity of punishment must be resorted to: He then sentenced George Smelt, Robert Crowe, and John James Bezer to be imprisoned in the house of correction for two years, to pay a fine of £10 each to the Queen, and at the expiration of their imprisonment to enter into their own recognizances in £100 with two securities of £50 each, to keep the peace for five years." (26)

Robert Crowe and the other Chartist prisoners were sent to the Westminster House of Correction. In the next cell was Ernest Jones, one of the leaders of the movement: "Passing over a number of minor incidents which occurred during my stay, let me present to the readers, my next door neighbour, or to be more precise, my next cell mate, Ernest Charles Jones, leader, lawyer, poet, lecturer, editor; a man small in stature, but large of heart, large of intellect, but largest in patriotism, an aristocrat by birth and connection, a patriot by choice. Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, and then King of Hanover, was his godfather." However, because of the "silent system, the most infernal contrivance ever invented for torturing human beings that ever emanated from the perverted ingenuity of man, together with the system of exclusiveness that prevailed, you may be sure we never spoke as we passed by. Indeed, it was like catching a momentary glimpse of God's sunshine in a dark cell to see his face while exercising in a corner of the yard." (27)

Crowe found prison life difficult: "That the monotony of prison life affords but few moments of relief scarcely admits of questions – the 'Argus' eyes of someone of the fifty-four officers, whose only chance of promotion over their fellows is vigilance in detecting the slightest violation of rules. And those rules. Silence night and day must be observed – at meals, exercise or passage from one part of the prison to another, in workshop, oakum room or chapel, making signs passwords or turning your head to the right or left, each prisoner being required to look straight before him, and much more of the same sort, all of which offences to be punishable by bread and water, or handed over to the visiting magistrates if any of the above offences were reported. (28)

Christian Socialism

Robert Crowe was released from prison in the summer of 1850. "On Monday morning, at 6 am nearly 2,000 persons assembled at the gate to greet me as I crossed the threshold." (29) The Christian Socialist movement had been monitoring the situation and was keen to set up a series of cooperatives. Charles Kingsley, Crowe's old friend, had commented: "Competition is put forth as the law of the universe. That is a lie. The time has come for us to declare that it is a lie by word and deed. I see no way but associating for work instead of for strikes." (30)

With the financial support of John Ludlow and Edward Vansittart Neale the group established the Tailors' Cooperative Association. Walter Cooper was appointed manager and Gerald Massey as bookkeeper. A committee was elected to raise money for rent, purchase of material and cash in hand for wages, a sum of £350. Operating rules were formulated and a house in Castle Street was hired. (31)

Crowe later explained that: "A few days later (after my release from prison) I received an invitation from the manager of the Tailors' Cooperative Association, Walter Cooper, offering me the privilege of work. I accepted and have commenced my acquaintance with the young and gifted poet, Gerald Massey, whose Lyrics of Freedom have become favourites with all liberal minds throughout the Kingdom. He was the bookkeeper to the association. (32)

However, the Tailors' Cooperative was forced to close when Walter Cooper, who was a poor manager, absconded with some of its fund. (33) Crowe, now unemployed decided to move north in search of work. "I tramped to Birmingham, about twenty-eight miles, and arrived late in the evening, exhausted, footsore and hungry, for my only companion on the journey was an empty pocket... Failing to obtain work in Birmingham, I settled down in the village of Smethwick, three miles distant." (34)

Travels to America

After experiencing several periods of unemployment Robert Crowe decided to emigrate to America (35). Crowe later wrote about this journey in his autobiography: "In the winter of 1854 I decided to leave England for America, and took passage in a crazy sailing vessel of the famous Tapscott Line, the Andrew Foster. For six weeks and four days the old hulk tossed about, during which time we lost, out of 504 steerage passengers, sixteen by ship fever and two by accident, thus compelling the captain to take a more northerly course… A letter of recommendation from a son in Birmingham to his father, a merchant tailor in Court Street, Brooklyn, procured me immediate work. I remained here nearly twelve months. I soon discovered that my boss (Mr Ball) was one of the ushers of Plymouth Church. So, I enjoyed the privilege of listening to that gifted orator, Henry Ward Beecher." (36)

Crowe joined a debating society, "known as the People's Meeting, and which held regular sessions every Sunday afternoon, at 183 Bowery, for twenty years, became to me an object of special interest. I took an active part in many of the debates. The question of slavery was under discussion for several weeks, and I was appointed to open the debate in a thirty-minute speech. A somewhat boisterous discussion followed, in which the most noise was on the pro-slavery or Democratic side." (37)

At first Crowe had a successful career as a tailor. However, the American Civil War created serious problems for the industry. "As a necessary result of the war, the price of every article consumed by the people was suddenly inflated. Rents went up, specie vanished out of sight, paper currency flooded the market, postage stamps took the place of money; common muslin that sold in the early part of 1860 for 6 cents per yard sold now for 80 cents per yard… In 1862 I commenced, in company with about seven others, to organize the Custom Tailors' Trade Protective and Benevolent Union." (38)

According to The Tailor & Cutter: "At that time the highest price paid for a frock or dress coat in the best firms was about 24s. Mr Crowe was elected secretary of the new organisation, and in less than six months the price of garments was doubled and the membership of the organisation totalled 2,000. His energy and organising ability were much sought after by other tailors than those of New York and Brooklyn, and branches sprang up in many places. (39)

Crowe became a follower of Henry George after the publication of Progress and Poverty (1877). "It is not unreasonable that, approaching the closing incident of my career, somewhat checkered career) with which I have been so closely identified, the grand scheme propounded by that distinguished political economist, Henry George, in contradiction to the present unequal division of wealth, formed, to my mind, the foundation of a truer civilisation than that which at present exists; and having read his great work, Progress and Poverty, I became convinced that his theories reduced to practice would tend to establish a more equitable relationship between labour and capital than can possibly be brought about by the present system." (40)

In 1883 Robert Crowe presiding over the first National Convention of Tailors in America. The gathering took place in Philadelphia and from it spring the Journeymen Tailors Union of North America. This organisation has spread itself all over the United States, and under the name of the Custom Tailors Union of America, have somewhere about 400 branches, and are affiliated to the American Federation of Labor. (41)

After he retired, Robert Crowe was persuaded by Helen Burns, principal of the non-denominational Cooper Settlement in New York, to write his autobiography. Comprised of 48 very short chapters, Reminiscences of an Octogenarian was published in 1902. (42)

In 1905 Robert Crowe had to undergo several severe operations on account of defective sight, but these were all unavailable, and by the following year he had became totally blind. He had been in receipt of an annuity for the last two years as the central federated unions of New York raised a fund for his relief. (43)

Robert Crowe died in New York, USA on 19th August 1907 and is buried at Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, Queens County, New York, United States. (44)

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

First, from infancy up, it has been my lot to be surrounded by poverty, no silver spoon being in my mouth when I came into the world.

Second, my education was rather, limited, being continued to the national school, and costing only one penny weekly. Attendance at school terminated in my fourteenth year, and about eighteen months of that time, employed as monitor over minor classes, and thus deprived of obtaining a fair amount of instruction, but earning enough to pay for my clothing.

Third, when appreciated, denied the luxury of reading, and used as a domestic drudge.

And lastly, dragged through the sweating dens of London, to protect myself in my trade, and eke out a scanty living.

(2) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

Three years of bitter persecution, during which time I became a mere domestic drudge, far more expert in cooking and nursing than tailoring, for my brother, who was considered as one of the best coatmakers in London, lived exclusively a dual life. One half hard work night and day, when occasion offered; the other half, drinking his earnings, and his wife's as well, for I never remember him to have spent one hour on the board that his wife was not by his side. She was remarkably gifted as a sewer. Poor fellow, he seemed to have no control over his appetite. Four of five pounds would slip through his fingers in one night, and so for the coming week we were put to the severest straights to live.

At last I mustered courage enough to snap the bonds and fling myself into the arms of the London sweating system, where, with all its repulsive features, I became more proficient in six months than I had been during the three years of my apprenticeship.

(3) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

In 1842 I was induced, through the entreaty of a friend, to allow myself with a juvenile temperance society. I took the pledge and remained faithful to the principle for twenty-five years.

In 1843 I commenced to advocate the cause publicly, but I was not slow to discover my deficiency as a speaker. I realised there was something needed, so I adopted the following novel expedient. I selected a retired, secluded spot (Soho Square), and every night, after 11 p.m., and continuing for about three months, I made the railings and trees my imaginary audience and soon learned to shudder at the echo of my voice.

(4) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

Before I reached my nineteenth year (1843) my spare time was divided between three public movements under Father Mathew, the repeal movement under Daniel O'Connell and the Chartist or English movement under Fergus O'Connor. In the bewildering whirl of excitement in which I lived during these years, I seemed almost wholly to forget myself. Night brought with it long journeys to meetings and late hours, though the day brought back the monotony of the sweater's den.

An amusing incident occurred in one of those meetings, which in this connection deserves a place as illustrating the ready wit which Daniel O'Connell was gifted. The government employed a well-known stenographer named Hughes to attend these meetings and make correct reports of all speeches for future use. When O'Connell arouse to address meetings and make correct reports of all speeches for future use. When O'Connell arose to address the meeting, he turned to the direction where Mr Hughes was sitting, and shouted in the rich Irish brogue for which he was distinguished:

"Mr Hughes, are you ready to proceed?"

Mr Hughes answered: "I am, Mr O'Connell."

Then O'Connell commenced one of his most remarkable speeches, which lasted over two hours.

(5) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

The Rev. Charles Kingsley, while engaged collecting material for his great work, Alton Locke, a work which has unquestionably done more to expose the pernicious nature of the sweating system than all other agencies put together, was informed that I, having worked in some of the sweating cribs of London, might furnish him with useful information on the subject, and sent me an invitation, which I was not slow to avail myself of…

Of my impressions of the man, I can only say that nothing struck me so forcibly as the ready power with which he was gifted of making one feel at home in his presence. He had a manly, open countenance, the genuine English contour of features, a winning smile that perpetually played over his face, and above all, brilliant eyes that never seemed to rest, deep set beneath heavy brows.

(6) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

A convention was called and a day fixed for the presentation of the national petition praying for the enactment of the People's Charter. The day, the 10th of April, 1848, memorable in the history of the time, was selected for the occasion.

A petition containing 3,500,000 signatures was prepared, and the procession which accompanied the same to the place of the meeting (Kennington Common) was certainly the largest and most imposing I ever participated in.

(7) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

Such was the condition when we marched over the bridges, eight abreast, on our way to Kennington Common, but no sooner did the procession pass over than the police and soldiery took possession of the bridges, and for nearly three hours we were held as prisoners…. At length the order was revoked, and the crowd was permitted to pass, and all went off quietly. Following quickly on the heels of the above action the Government started a series of prosecutions commencing the following month (May) with a batch of five – Ernest Charles Jones, a barrister and our leader; John Fussell, Sharp, Williams and Dr. Vernon. (page 9)

(8) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

Then came the second batch, consisting of thirty-two, of whom I had the honour to be one… The six weeks of our detention in Newgate prior to trial hung heavy on our hands, enlivened only by the occasional glance at the notorious William Calcraft, England's public executioner, and Chaplain Davis, the alleged "man of God." We used to see them while they were engaged in inspecting the gallows and conferring on the preliminaries of an execution to take place in front of the jail on the following morning.

Another gala day in the Old Bailey, when the political prisoners are placed in a row in front of the dock to receive sentence; again the court is crowded with a fashionable throng, and at the opportune time the Attorney-General rises, his pale face suffused with a cold, sardonic, sickly sneer and conjures his lordship to "pass a heavy sentence3 on the prisoner Crowe, because of the dangerously seductive and poetic character of his eloquence and its influenced on the minds of his uneducated hearers: and his lordship, who no doubt like another Barkis, was only two willing to oblige, passed the following sentence: To be continued in the Westminster House of Correction for the term of two years, with hard labour, and at the expiration of said term to give bonds myself of £100, and two additional securities (householders) at £50 each, to keep the peace with Her Majesty's subjects for the term of five years, and in addition to pay for Her Majesty the sum of £10.

(9) The Leicestershire Mercury (2nd September 1848)

John James Bezer was indicted for sedition. The Attorney-General, Mr Welby, Mr Bodkin, and Mr Clark, appeared for the Crown. The defendant had no counsel, but more of a defence in the opinion he had expressed of the dangerous description of ability possessed by the defendant. The jury returned a verdict of guilty; and the other defendants who had been convicted to receive sentence. Mr Baron Platt in passing sentence, addressed them at some length upon their conduct, and told them as the sentence passed upon them at a previous session did not appear to have deterred them, it was clear an increase of severity of punishment must be resorted to: He then sentenced George Smelt, Robert Crowe, and John James Bezer to be imprisoned in the house of correction for two years, to pay a fine of £10 each to the Queen, and at the expiration of their imprisonment to enter into their own recognizances in £100 with two securities of £50 each, to keep the peace for five years.

(10) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

Passing over a number of minor incidents which occurred during my stay, let me present to the readers, my next door neighbour, or to be more precise, my next cell mate, Ernest Charles Jones, leader, lawyer, poet, lecturer, editor; a man small in stature, but large of heart, large of intellect, but largest in patriotism, an aristocrat by birth and connection, a patriot by choice. Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, and then King of Hanover, was his godfather.

What with the accursed "silent system", the most infernal contrivance ever invented for torturing human beings that ever emanated from the perverted ingenuity of man, together with the system of exclusiveness that prevailed, you may be sure we never spoke as we passed by. Indeed, it was like catching a momentary glimpse of God's sunshine in a dark cell to see his face while exercising in a corner of the yard. (page 12)

That the monotony of prison life affords but few moments of relief scarcely admits of questions – the "Argus" eyes of someone of the fifty-four officers, whose only chance of promotion over their fellows is vigilance in detecting the slightest violation of rules. And those rules. Silence night and day must be observed – at meals, exercise or passage from one part of the prison to another, in workshop, oakum room or chapel, making signs passwords or turning your head to the right or left, each prisoner being required to look straight before him, and much more of the same sort, all of which offences to be punishable by bread and water, or handed over to the visiting magistrates if any of the above offences were reported.

A few days later I received an invitation from the manager of the Tailors' Cooperative Association, Walter Cooper, offering me the privilege of work. I accepted and have commenced my acquaintance with the young and gifted poet, Gerald Massey, whose "Lyrics of Freedom" have become favourites with all liberal minds throughout the Kingdom. He was the bookkeeper to the association.

George Julian Harney was then publishing a weekly journal called The Red Republican, and Massey was contributing some of his best poems to it. But the dose evidently proved too much for some of the aristocratic patrons of the Cooperative, contributing to Harney's journal. So, he apparently withdrew.

(11) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

In the winter of 1864 I decided to leave England for America, and took passage in a crazy sailing vessel of the famous Tapscott Line, the Andrew Foster . For six weeks and four days the old hulk tossed about, during which time we lost, out of 504 steerage passengers, sixteen by ship fever and two by accident, thus compelling the captain to take a more northerly course…

A letter of recommendation from a son in Birmingham to his father, a merchant tailor in Court Street, Brooklyn, procured me immediate work. I remained here nearly twelve months. I soon discovered that my boss (Mr Ball) was one of the ushers of Plymouth Church. So, I enjoyed the privilege of listening to that gifted orator, Henry Ward Beecher...

(12) Robert Crowe, The Reminiscences of Robert Crowe, the Octogenarian Tailor (1902)

It is not unreasonable that, approaching the closing incident of my career, somewhat checkered career) with which I have been so closely identified, the grand scheme propounded by that distinguished political economist, Henry George, in contradiction to the present unequal division of wealth, formed, to my mind, the foundation of a truer civilisation than that which at present exists; and having read his great work, Progress and Poverty, I became convinced that his theories reduced to practice would tend to establish a more equitable relationship between labour and capital than can possibly be brought about by the present system.

(13) The Tailor & Cutter (19th September 1907)

There has just passed away in the Metropolitan Hospital at New York, a very notable character, and one who played a very prominent part of the history of the tailoring trade both in England and America. Mr Robert Crowe, to whom we refer, was one of the leaders of the London tailors back in the early forties of the last century, and was prominent in the strike of tailors which took place in 1845. He was then a young man of 22, and had been a journeyman about twelve months. His ideas were far in advance of his years, however, and his advocacy of a reform movement had no small share in bringing that trade to a head. He was an Irishman by birth, having been born in Ireland in 1823.

In 1837 he came, with his elder brother, to London, and was apprenticed to the tailoring trade by him. He came under the influence of Father Matthew, the great temperance advocate, early in life, and up to the end was a strong advocate of temperance himself. He figured, also, in the Repeal Movement, under Dan O'Connell, and in the great Chartist movement; indeed, it was this latter movement which caused him to take his departure for America. The state of the tailoring trade in London in his apprentice days was something dreadful, and, notwithstanding the deplorable conditions under which life had to work and learn his trade, he found time to educate himself, and to make himself acquainted with the political and social movement going on in London during these years. When his apprenticeship was completed, he threw all the energy he possessed, and all his undoubted eloquence into the trade union movement which had been revived after a lapse of many years, and put new heart into many who had tried, but been beaten, in 1832. Had all the tailors whom he succeeded in rousing, been so careful and steady as he was himself, the strike of 1845 would have had a different ending. As it was, it failed but Crowe did not lose heart, nor relax effort, and had another try in 1849.

The failure of these trade movements threw him into the wider turmoil of the two great national movements mentioned above, in both of which he became a leading figure.

In 1854 Mr Crowe went to America and started to work for a firm in Brooklyn. He soon made his appearance on temperance platforms, and, later, threw himself into the anti-slavery movement.

Mr Crowe found the state of the tailoring trade in America very much the same as he had left behind in England, and in 1862 set himself to bring about some improvement. He influenced a few other tailors to join with him in that work, and some eight or nine of them formed the first branch of the Custom Tailors Trade Protection and Benevolent Union.

At that time the highest price paid for a frock or dress coat in the best firms was about 24s. Mr Crowe was elected secretary of the new organisation, and in less than six months the price of garments was doubled and the membership of the organisation totalled 2,000. His energy and organising ability were much sought after by other tailors than those of New York and Brooklyn, and branches sprang up in many places.

In 1883 he saw the fruits of the seed he had sown, for he had the honour of presiding over the first National Convention of Tailors in America. The gathering took place in Philadelphia and from it spring the Journeymen Tailors Union of North America. From the North, this organisation has spread itself all over the States, and under the name of the Custom Tailors Union of America, have somewhere about 400 branches, and are affiliated to the American Federation of Labour.

About two years ago Mr Crowe had to undergo several severe operations on account of defective sight, but these were all unavailable, and about the commencement of this year he became totally blind. He had been in receipt of an annuity for the last two years as the central federated unions of New York raised a fund for his relief.

�