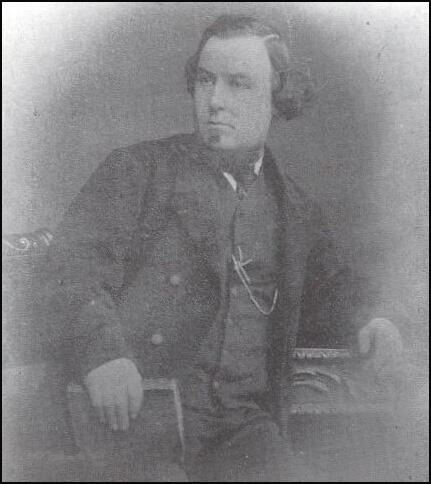

John James Bezer

John James Bezer was born on the 24 August 1816 in his father's one room barber's shop in Hope Street, Spitalfields, and baptised on the 15 September 1816 at Spitalfields Christ Church Stepney. (1)

As a baby he caught smallpox. In his autobiography, he recalled what happened: "Six months after my birth, my left eye left me for ever, the small pox, the cause. For two months I was totally blind, and very bad, the faculty giving me over for dead more than once. The 'faculty' were wrong; I recovered, minus an eye, and often have I been nearly run over through having a 'single eye' towards the road; and often have I knocked against a dead wall, and hugged it as if I really loved the dark side of a question." (2)

Bezer had little formal education but enjoyed going to Sunday School: "My education was very meagre. Among the many days I shall probably for life remember, is the 21st of December, 1821, when breeched for the first time, and twopence in my brand new pocket, I proudly marched to Raven Row Sunday School and had my name entered. From that hour, until the hour I finally left, which, with the exc eption of two intervenings of short duration, lasted nearly fifteen years, I can truly say I loved my school, no crying when Sunday came round." (3)

Bezer's father was a violent drunkard. "Father was a drunkard, a great spendthrift, an awful reprobate. Home was often like a hell; and "Quarter days" - the days father received a small pension from Government for losing an eye in the Naval Service - were the days mother and I always dreaded most; instead of receiving little extra comforts, we received extra big thumps, for the drink maddened him." (4)

Childhood of John James Bezer

The family became out-door paupers, the parish allowing them four shillings per week. (5) "Our little home, which though humble, had become precious to us, was broken up, the persecuted saint went to Greenwich College, and mother and I became out-door paupers to a parish in the City that father claimed through his apprenticeship. All these things were against us, except that they made a lasting impression on my youthful mind, and I stuck to my Sunday school and to my faith with all the fervour and enthusiasm God had given me." (6)

James and his mother struggled on this income and had to resort to buying and selling bread: "The parish allowed us four shillings weekly, and with that miserable stipend, and about two shillings more for cotton winding, we managed to pay rent and buy bread till the near approach of Easter in the next year; then we bought buns not for the purpose of eating, (though we did eat them after all), but for the purpose of selling again. Three shillings and one little basket were borrowed for this important occasion: - mother put two shillings' worth of buns in the basket, and one shilling's worth in the tea-tray for me, and off we trudged different ways. Mother had given me my round, but then it was much nearer home and Sunday school than I cared about, and worse still, it was a leading thoroughfare. Did I want people to see me? No. - if people couldn't buy buns without seeing the seller, it was strange, so with aching heart, and scalding tears, and scarlet face, I walked up and down the most by-streets, and whispered so low that nobody could hear me." (7)

At nine years of age, young Bezer obtained his first post as a warehouse errand boy in Newgate Street. Working a 17 hour day for a six-day week, he received three shillings. (8) In 1827, aged eleven, he became very ill with typhus and "for weeks I was to all appearance dying. I was glad to hear that the parish doctor gave me up, and the farewell of my teachers and my fellow Sunday scholars I loved so well, and my poor dear father who crawled on crutches to see me, was, though affecting, happiness to me. I felt an ardent desire for death - but it was not to be. I at last recovered. (9)

James Bezer did various jobs including, cordwinder, shoemaker and fishmonger. In 1837, he married Jane Sarah Drew at Christchurch Newgate Street, and the birth of their first child occurred the following year. Francis James Bezer was born at 6 am on 6 February 1838 at 30, Back Hill, Saffron Hill. At that time he was jobless, and reduced to singing hymns and begging. This was followed by Jane Sarah (1839 died later that year) and Jane Mary (1840). (10)

In the 1841 census returns the family were living in at 2 Baldwin's Place, Baldwin's Gardens, Holborn. Baldwin's Place was situated off Gray's Inn Road between what is now Baldwin's Gardens and Portpool Lane. Bezer is listed as aged 25, a Journeyman Shoemaker with his wife 25, a Dressmaker, and Jane Bezer, 9 months. Her son, Francis James, is not listed and is probably dead by this time. (11)

Chartism

In the early 1840s Bezer was unemployed for long periods of time. In an article published in The Christian Socialist he explained how he became a Chartist. "I went down downstairs to the landlord to pay him a week's rent out of the four I owed him, and the good fellow said, 'Never mind, if you haven't yet got any work, I don't take any till you do, I'm sure you'll pay me – how long have you been out of work?' 'Near seven months,' I said, with a sigh, thinking more of the dogs I had encountered in the day than anything else. 'Ah,' says he, 'there'll be no good done in this country till the Charter becomes the law of the land.' 'The Charter?' 'Yes, I am a Chartist – they meet tonight at Lunt's Coffee House on the Green – will you come?' 'Yes.' It was only a 'Locality' meeting, but there were about sixty people present, and as one after another got up, oh, how I sucked in all they said!' 'Why should the many starve, while the few roll in luxuries? Who'll join us, and be free?' 'I will,' cried I, jumping up in the midst. 'I will, and be the most zealous among you – give me a card and let me enrol.' And so… I became a Rebel; - that is to say: - Hungry in a land of plenty, I began seriously for the first time in my life to enquire why, why – a dangerous question… isn't it, for a poor man to ask?" (11a)

John James Bezer eventually became Secretary of the Cripplegate Locality of the National Charter Association, and became speaking at their meetings. He also found work as a labourer. His wife continued to give birth to more children: Emily Drew (1843), Frederick John (1844), Mary Nelson (1846) and Walter Cooper (1848). At this time he was living at 2, Shepherd and Flock Court, Little Bell Alley. (12)

Feargus O'Connor, editor of The Northern Star, organized a National Petition that demanded parliamentary reform. At the meeting held at Kennington Common on 10th April 1848, O'Connor told the crowd that the petition contained 5,706,000 signatures. However, when it was examined by MPs it contained only 1,975,496 names and many of these, such as, those of well known opponents of parliamentary reform, Queen Victoria, Sir Robert Peel and the Duke of Wellington, were clear forgeries. (13)

The Times reported that around 50,000 people took part in the Chartist demonstration. (14) The government became concerned about the support that the Chartist movement was achieving and decided to pass new legislation against the freedom to protest. Parliament passed the Treason and Felony Act. It was a far reaching measure that redefined and extended the offence of treason, including a new treasonable offence of "open and advised speaking". (15)

Bezer reacted to the rejection of the Chartist Petition by joining what became known as the Physical Force Chartists. Oneoftheleadersofthis group was William Cuffay. A police spyreported that at a meeting Cuffay gave instructions on how to make cartridges and bullets. "He also said that Ginger Beer bottles filled full of nails and ragged pieces of iron were good things for wives to throw out of the windows while the men were down in the streets fighting the police." Soon afterwards Cuffay was arrested and charged with sedition. (16)

John James Bezer became an active member of the Irish Democratic Confederation of London - a strongly militant group that had Feargus O'Connor as president. The objectives of this Confederation included the repeal of the Union between Great Britian and Ireland and the establishment of a representative parliament. Bezer had lectured on the Irish question as well as on Chartist themes at various venues throughout the previous twelve months, including Cartwright's Coffee House in Cripplegate and the Star Coffee House Redcross Street in Golden Lane. (17) At a public meeting held on 22nd June, 1848, he complained about the police action against Chartists. At this meeting, Bezer moved "That making the police a military body was subversive of liberty, and the British Constitution." (18)

Bezer now became one of the Chartists most popular speakers. At one meeting he joined Bronterre O'Brien and Gerald Massey on the stage. Bezer read several extracts from an American newspaper "showing that poverty and pauperism prevailed in the States and that even the Republican institutions were not complete if confined to mere politics. That showed the necessity for social rights, such as the nationalisation of the land etc. Bezer continued by quoting many great authors in favour of equality of rights, and appealed to the audience not to heed mere names, but to stand by principles. He sat down to loud applause." (18a)

On the 26 July 1848 Bezer attended a meeting chaired by John Shaw of the City Lecture Theatre, Milton Street, Cripplegate, where the subject was "Of bringing before the Legislature and the Public the despotic treatment of the Chartist victims." A strong force of police was standing by in case of disturbance. Two days later, at the same venue, Bezer conducted a public meeting condemning the Government's handling of the current problems in Ireland. It was reported that some 1,000 persons mostly Irish were in attendance both inside and outside the hall. Also present were the police and reporters who took notes of what men said at the meeting. (19) Several men at the meeting, including Bezer, Robert Crowe (tailor), George Shell (shoemaker) and John Maxwell Bryson (dentist) were arrested and charged with sedition. (20)

In court it was claimed that Bezer had called on Chartists "to destroy the power of the Queen, and establish a Republic." Bezer was accused of telling people that he would be able to supply 50 fighting men, and that they "were going to get up a bloody revolution". Bezer, Shell, Bryson and Crowe were all found guilty of sedition. According to The Leicestershire Mercury "The jury returned a verdict of guilty; and the other defendants who had been convicted to receive sentence. Mr Baron Platt in passing sentence, addressed them at some length upon their conduct, and told them as the sentence passed upon them at a previous session did not appear to have deterred them, it was clear an increase of severity of punishment must be resorted to: He then sentenced George Smelt, Robert Crowe, and John James Bezer to be imprisoned in the house of correction for two years, to pay a fine of £10 each to the Queen, and at the expiration of their imprisonment to enter into their own recognizances in £100 with two securities of £50 each, to keep the peace for five years." (21)

John James Bezer, Robert Crowe and the other Chartist prisoners were sent to the Westminster House of Correction. Crowe later wrote about his experiences. In the next cell was Ernest Jones, one of the leaders of the movement: "Passing over a number of minor incidents which occurred during my stay, let me present to the readers, my next door neighbour, or to be more precise, my next cell mate, Ernest Charles Jones, leader, lawyer, poet, lecturer, editor; a man small in stature, but large of heart, large of intellect, but largest in patriotism, an aristocrat by birth and connection, a patriot by choice. Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, and then King of Hanover, was his godfather." However, because of the "silent system, the most infernal contrivance ever invented for torturing human beings that ever emanated from the perverted ingenuity of man, together with the system of exclusiveness that prevailed, you may be sure we never spoke as we passed by. Indeed, it was like catching a momentary glimpse of God's sunshine in a dark cell to see his face while exercising in a corner of the yard." (21a)

Crowe found prison life difficult: "That the monotony of prison life affords but few moments of relief scarcely admits of questions – the 'Argus' eyes of someone of the fifty-four officers, whose only chance of promotion over their fellows is vigilance in detecting the slightest violation of rules. And those rules. Silence night and day must be observed – at meals, exercise or passage from one part of the prison to another, in workshop, oakum room or chapel, making signs passwords or turning your head to the right or left, each prisoner being required to look straight before him, and much more of the same sort, all of which offences to be punishable by bread and water, or handed over to the visiting magistrates if any of the above offences were reported. (21b)

William Cuffay was convicted and sentenced to be transported to Tasmania for 21 years. Cuffay issued a statement after his conviction: "The present Government is now supported by a regular organized system of espionage which is a disgrace to this great and boasted free country.... I say you have no right to sentence me. Although the trial has lasted a long time, it has not been a fair trial, and my request to have a fair trial - to be tried by my equals - has not been complied with. Everything has been done to raise a prejudice against me, and the press of this country - and I believe of other countries too - has done all in its power to smother me with ridicule. I ask no pity. I ask no mercy. I expected to be convicted, and I did not think anything else. No, I pity the Government, and I pity the Attorney General for convicting me by means of such base characters. The Attorney General ought to be called the Spy General. I am not anxious for martyrdom, but after what I have endured this week, I feel that I could bear any punishment proudly, even to the scaffold." (22)

On his release a meeting was immediately convened by the provisional committee of the National Charter Association, and was held at the John Street Institution on 23 April 1850. Thirteen of the released Chartists mounted the platform, and spirited addresses were made by committee members, including James Bronterre O'Brien and George Julian Harney. John James Bezer, was introduced, and addressed the packed hall amid loud cheering. Massey said in conclusion that: Ernest Jones, a true poet of labour, had thought that Englishmen would have been prepared for the revolution, but misery and degradation had done their work. The people had fallen a prey to priests, who preached of gods of wrath, and of hells of torture as though they were the devil's own salamanders. But the day would come when thrones and aristocracies would no longer hang as millstones round their necks." (22a)

John James Bezer went on a tour of the country talking about his prison experiences. The Red Republican reported: "This sterling democrat who suffered nearly two years' incarceration in Newgate, for advocating the principles of the People's Charter, is about to take a tour through the country and proposes to deliver lectures in all the principal towns. The sufferings of himself and fellow-victims in prison - the principles of democratic and social reform, and the united organisation of democratic and social reformers to obtain the Charter, will form the leading topics of Mr Bezer's lectures... Mr Bezer deserves, and we doubt not will receive, a hearty welcome from the 'Reds' in all parts of England." (23)

Christian Socialism

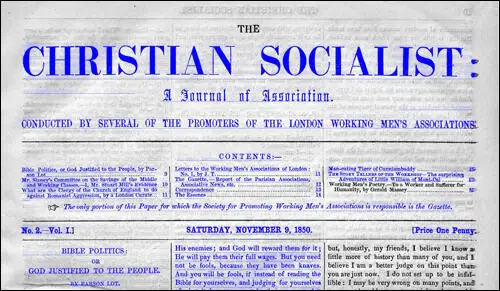

A group of Christians who supported parliamentary reform were known as Christian Socialists. This included Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley, John Ludlow, Thomas Hughes, Charles Blachford Mansfield, Edward Vansittart Neale, John Bedford Leno, Lloyd Jones, and Frederick James Furnivall. On 2nd November, 1850, the group launched a new journal, The Christian Socialist. On its first page it stated what it was trying to do: "A new idea has gone abroad into the world. That is Socialism, the latest-born of the forces now at work in modern society, and Christianity, the eldest born of those forces, are in their nature not hostile, but akin to each other, or rather that the one is but the development, the outgrowth, the manifestation of the other, so that even the strangest and most monstrous forms of Socialism are at bottom but Christian heresies. That Christianity, however feeble and torpid it may seem to many just now, is truly but as an eagle at moult, shedding its worn-out plumage; that Socialism is but the livery of the nineteenth century (as Protestantism was its livery of the sixteenth) which is now putting on, to spread long its mighty wings for a broader and heavenlier flight. That Socialism without Christianity, on the one hand, is as lifeless as the feathers without the bird, however skilfully the stuffer may dress them up into an artificial semblance of life; and that therefore every socialist system which has endeavoured to stand alone has hitherto in practice either blown up or dissolved away; whilst almost every socialist system which has maintained itself for anytime has endeavoured to stand, or unconsciously to itself has stood, upon those moral grounds of righteous, self-sacrifice, mutual affection, common brotherhood, which Christianity vindicates to itself for an everlasting heritage." (24)

John Ludlow, the editor of this new venture, pointed out in his first editorial: "We do not mean to eschew Politics.We shall have Chartists writing for us, and Conservatives, and yet we hope not to quarrel, having this one common ground of Socialism, just as on the ground we hope not to quarrel, though the professing Christian be mixed in our ranks with those who have hitherto passed for Infidels." It was announced in the first edition that the journal would cover the entire spectrum of English life: free trade, education, the land question, poor laws, reform of the law, sanitary reform, taxation, finance, and Church reform. (25)

John Ludlow was the editor of this new venture. It was to be a rule of the journal that writers should be anonymous, a common practice of the time. Ludlow's pen-name was John Townsend, or J.T. It was announced in the first edition that the journal would cover the entire spectrum of English life: free trade, education, the land question, poor laws, reform of the law, sanitary reform, taxation, finance, and Church reform. John Bezer was asked to write for the journal and he used the pen-name "Chartist Rebel". (25a)

Soon afterwards Bezer met John Bedford Leno and it was decided that they should a printers's cooperative, and the The Christian Socialist journal became its main customer. Ten chapters of Bezer's autobiography were published as instalments in the journal from 9 August 1851. David Shaw has argued that the autobiography "considering the circumstances, surprisingly well written - record forms both an interesting and an important portrayal, at first hand, of working-class life in Dickensian London." (26)

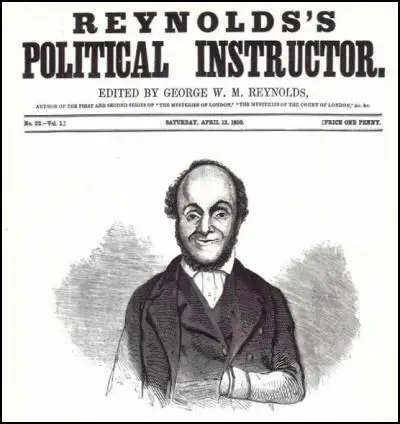

George Julian Harney, a great supporter of John James Bezer, was disgusted by this development. Harney had used his newspaper, The Red Republican to promote Physical Force Chartism. With the help of his friend, Ernest Jones, Harney attempted to use his paper to educate his working class readers about socialism and internationalism. Harney also attempted to convert the trade union movement to socialism. Harney knew that the The Christian Socialist movement was totally opposed to the use of violence and feared that Bezer had "gone over to the enemy". (27)

Bezer and Leno used the office of the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations, at 183 Fleet Street. However, the journal ran into financial difficulties, and was discontinued in December of that year, although reviving temporarily from 3 January to 28 June the following year as the Journal of Association. (28)

John James Bezer (Drew) died on the 12 January 1888, aged 71, and was buried at Carlton Old Melbourne Cemetery (Grave, Wesleyan Methodist F 705). There is no headstone. He had suffered a stroke a fortnight earlier at his daughter's home at Moray Place, South Melbourne.

Primary Sources

(1) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (9th August 1851)

Six months after my birth, my left eye left me for ever, the small pox, the cause. For two months I was totally blind, and very bad, the "faculty" giving me over for dead more than once. The "faculty" were wrong; I recovered, minus an eye, and often have I been nearly run over through having a "single eye" towards the road; and often have I knocked against a dead wall, and hugged it as if I really loved the dark side of a question. Ah, I've had many a blow through giving half a look at a thing! How many times since I became a costermonger has a policeman hallooed in my ear, "Come! move hon there, vill yer! now go hon, move yer hoff!" while I've actually thought he was on duty in some kitchen with the servant girl, taking care of the house as the master and mistress were out. It was not however so; there he has stood in all his beauty, a Sir Robert Peel's monument�a real one, alive,�and sometimes have I seen him kicking.

My education was very meagre; I learnt more in Newgate than at my Sunday school, but let me not anticipate. Among the many days I shall probably for life remember, is the 21st of December, 1821, when breeched for the first time, and twopence in my bran-new pocket, I proudly marched to Raven Row Sunday School and had my name entered. From that hour, until the hour I finally left, which, with the exception of two intervenings of short duration, lasted nearly fifteen years, I can truly say I loved my school,�no crying when Sunday came round.

I yearned for it; - whether it was because my home was not as it ought to have been, (a painful subject I shall feel bound to say something about in due order,) or because association has ever seemed dear to me, or because I desired to show myself off as an apt scholar, or because I really wanted to learn, or all these causes combined - most certainly I was ever the first to get in to school, and the last to go out.

(2) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (16th August 1851)

I ought to have learned a great deal, say you, in fifteen years; well, in the opinion of some, I did, for notwithstanding the disadvantages I laboured under both at home and at school, and there only being six hours a week for me, I rapidly rose from class to class; at seven years old I was in the "testament class" - at eight, in the highest - shortly after, "head boy" - soon after that, "monitor" - at eleven, teacher - and long before I left, head teacher; - and yet, what had I learned? to read well, and that was all. Three years ago I knew nothing of arithmetic, and could scarcely write my own name.

I have just spoken of the disadvantages at school - I shall doubtless displease some of my readers in what I am going to say, but when I commenced this history, I determined that it should be a genuine one, and that I would put down my thoughts without reserve. Now, that school did not even learn me to read; six hours a week, certainly not one hour of useful knowledge; plenty of cant, and what my teachers used to call explaining difficult texts in the Bible, but little, very little else.

(3) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (24th August 1851)

Father kept a barber's shop, trade was brisk, and times much better than they are now, so that when he really did attend to his business; he cleared a good round sum weekly. Mother also earned at cotton winding (before machinery, or rather the monopoly of machinery altered it,) nine or ten shillings weekly; yet there we were, miserably poor, and the quotation at the head of this chapter was literally my experience for years during my childhood, except a few short months that I remained with my aunt, who, though well off, treated me shamefully, and I ran home again, that being the lesser evil.

Father was a drunkard, a great spendthrift, an awful reprobate. Home was often like a hell; and "Quarter days"�the days father received a small pension from Government for losing an eye in the Naval Service - were the days mother and I always dreaded most; instead of receiving little extra comforts, we received extra big thumps, for the drink maddened him. The spirit of the departed will pardon, and, I verily believe, will rejoice at my speaking thus plainly, not only because it is the truth, but in order to show, as I shall show, the power of Christian principles as exemplified in the after life of him who was as a "brand plucked from the burning."

Father had been an old "man-o'-wars man," and the many floggings he had received while serving his country, had left their marks on his back thirty years afterwards; they had done more, - they had left their marks on his soul. They had unmanned him; can you wonder at that? Brutally used, he became a brute - an almost natural consequence; and yet there are men to be found even to this day, advocates of the lacerating the flesh and hardening the hearts of their fellow creatures simultaneously.... Mother's work also got slack and worse paid. Still they persevered, and still things got worse, and though "a dry morsel with quietness" was a glorious improvement on the past, they could not at last meet the expenses of the veriest necessities of life. The climax to all was, that the Government pension was stopped altogether, in consequence of father petitioning for an increase, the authorities offering him the hospital. Our little home, which though humble, had become precious to us, was broken up, the persecuted saint went to Greenwich College, and mother and I became out-door paupers to a parish in the City that father claimed through his apprenticeship. All these things were against us, except that they made a lasting impression on my youthful mind, and I stuck to my Sunday school and to my faith with all the fervour and enthusiasm God had given me.

(4) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (31st August 1851)

The parish allowed us four shillings weekly, and with that miserable stipend, and about two shillings more for cotton winding, we managed to pay rent and buy bread till the near approach of Easter in the next year; then we bought buns not for the purpose of eating, (though we did eat them after all), but for the purpose of selling again. Three shillings and one little basket were borrowed for this important occasion:�mother put two shillings' worth of buns in the basket, and one shilling's worth in the tea-tray for me, and off we trudged different ways. Mother had given me my round, but then it was much nearer home and Sunday school than I cared about, and worse still, it was a leading thoroughfare. Did I want people to see me? No. - "if people couldn't buy buns without seeing the seller, it was strange," so with aching heart, and scalding tears, and scarlet face, I walked up and down the most by-streets, and whispered so low that nobody could hear me.

"If you please, Sir, do you want a boy? My name is -; mother winds cotton for you, sir; father is in Greenwich College, and we are in great distress - almost starving, sir; I'll be very willing to do anything." "Why, you're so little! What's your age?" "Past nine, sir, and I'm very strong!" "What wages do you want?" "Anything you please, sir." (The healthy competition was all one side.) "Well, come to-morrow morning, six o-clock, and if you suit I'll give you three shillings a-week; but bring all your victuals with you - we have no time for you to go home to your meals." Thus was I duly installed at a Warehouseman's in Newgate Street.

Black slavery is black enough, I doubt not, and white slavery is a very horrid thing in all its ramifications, for it has many - the factory children, and so on; - there is pity, however, manifested towards these unfortunates, and sometimes help, but who ever thought of errand-boy slavery? "Willing to do anything." Yes, and anything I did, - wait in the cold and sleet for half-an-hour each morning at master's street door�clean a box full of knives and forks, a host of boots and shoes in a damp freezing cellar - gulp down my breakfast, consisting of a hunk of bread, perhaps buttered, and a bason of water bewitched, called tea, in the cold warehouse - run to Whitechapel with a load they called a parcel - back again - "John, make haste to Piccadilly with this " - back again�"John, your mistress wants you to rub up the fire-irons and candlesticks, and clean the house windows" - "John, look sharp, and have your dinner, you're wanted to go over the water with a lot of things," (dinner! God help me! a penny saveloy when it was not in the dog days, and a "penn'orth of baked plain" when it was, or bread alone at the latter end of the week) - trail along with my bag full of "orders" along Blackfriars, Walworth, London Road, City, and back to Newgate Street�"John, look alive, of Islington Green, wants this parcel directly" - back again - "Now, John, all the 'orders' are ready for the West, so as soon as you've had your tea (tea!), you can start; you needn't come back here to-night,�bring the bag in the morning." Though master said my time was from six to eight, yet it was always half-past seven, sometimes later, ere I could start to the "West," which meant haberdashers shops up Holborn, Soho, Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly, over Westminster Bridge to two shops near the "Broadway," and then , eleven o'clock at the earliest, trudge home to Spitalfields, foot-sore and ready to faint from low diet and excessive toil, and this, too, for years without one day's intervention save Sundays, for my master was religious of course. Every night would I crawl home with my boots in my hand, putting them on again before I got in, trying to laugh it off while I sank on my hard bed saying, "never mind mother, I don't mind it, you know I'm getting bigger every day." Indeed 'tis hard

(5) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (7th September 1851)

Well, Father would come out of the College; he rallied somewhat, and went "a barbering" round Bethnal-green, a sort of itinerant shaver. The parish stopped the supplies immediately; but Father cleared about 6s. or 7s.�Mother about 3s. 6d., which, with my earnings, amounted to 13s. or 14s. per week;' provisions were dearer then than they are at the present time, yet as we were very economical, not only did we manage necessaries, but our home became gradually more comfortable. As winter, however, came on, Father's rheumatism - as bad an ism as a man can be plagued with, - I speak feelingly - laid him on his beam ends; and separation was again our fate. The "College" received him till he died. Mother, too, just at this time fell dangerously ill; and for many nights - hard as I worked in the day - I had no rest. God bless the poor! they saved her life when parish doctor, and parish overseer had passed her by, and said that the workhouse would take me, after they had buried Mother; - the poor neighbours - not the rich ones - played the part, as they always do, of good Samaritans, by rushing to the rescue, and nursing her in turns night and day for weeks, without fee, or thinking of fee. God bless the poor! Amen!...

Master's tyranny became more and more insupportable. I will give the reader an instance. In the second week of Mother's illness, I was sent to Mile-end Road with a parcel, and as we then lived in High-street, Mile End New Town, close by, nature predominated over my fear of offending, and I came home; it was thought Mother would not live an hour. I stayed that hour, and yet she breathed - and I ran back with quick step but heavy heart. "What has made you so long, sir?" I told him the truth, and he kicked me! I never remember feeling so strong, either in mind or body, as I did at that degrading moment; I threw the day-book at him with all my might, and before he could recover his presence of mind, sprang on the counter, and was at his throat. I received some good hard knocks, which I returned, - if not with equal force, - with equal willingness, crying, "Oh, if my poor Father were here," - "I'll tell Father" - "I'll go to the Lord Mayor"- "I'll tell everybody." The tustle didn't last long, and the result was that we gave each other warning; and I, nothing daunted, threatened to stand outside the street door, and create a crowd by telling every one as they passed all about it; whilst he threatened, in his turn, to give me into custody for tearing his waistcoat and assaulting him, saying I should get into Newgate Closet before I died. The spirit of prophecy must have manifested itself in a remarkable manner at that moment to that great man. For, lo! as he said, so it came to pass, though many years afterwards. I will not however, give him all the praise. The "signs of rebellion" were just then rather clear. I was, to all intents and purposes, a "physical force rebel," and I doubt not that "the coming event cast its shadow before".

(5) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (13th December 1851)

I went down downstairs to the landlord to pay him a week's rent out of the four I owed him, and the good fellow said, "Never mind, if you haven't yet got any work, I don't take any till you do, I'm sure you'll pay me – how long have you been out of work?" "Near seven months," I said, with a sigh, thinking more of the dogs I had encountered in the day than anything else. "Ah," says he, "there'll be no good done in this country till the Charter becomes the law of the land." "The Charter?" "Yes, I am a Chartist – they meet tonight at Lunt's Coffee House on the Green – will you come?" "Yes." It was only a "Locality" meeting, but there were about sixty people present, and as one after another got up, oh, how I sucked in all they said!" "Why should the many starve, while the few roll in luxuries? Who'll join us, and be free?" "I will," cried I, jumping up in the midst. "I will, and be the most zealous among you – give me a card and let me enrol." And so… I became a Rebel; - that is to say: - Hungry in a land of plenty, I began seriously for the first time in my life to enquire why, why – a dangerous question… isn't it, for a poor man to ask?

(5) The Leicestershire Mercury (2nd September 1848)

John James Bezer was indicted for sedition. The Attorney-General, Mr Welby, Mr Bodkin, and Mr Clark, appeared for the Crown. The defendant had no counsel, but more of a defence in the opinion he had expressed of the dangerous description of ability possessed by the defendant. The jury returned a verdict of guilty; and the other defendants who had been convicted to receive sentence. Mr Baron Platt in passing sentence, addressed them at some length upon their conduct, and told them as the sentence passed upon them at a previous session did not appear to have deterred them, it was clear an increase of severity of punishment must be resorted to: He then sentenced George Smelt, Robert Crowe, and John James Bezer to be imprisoned in the house of correction for two years, to pay a fine of £10 each to the Queen, and at the expiration of their imprisonment to enter into their own recognizances in £100 with two securities of £50 each, to keep the peace for five years.

(5) The Inverness Courier (5th September 1848)

On Monday, John James Bezer, 32, described as a labourer, was then placed in the dock, upon an indictment charging him with sedition. The Attorney General said the speech was delivered at a meeting held on the 28th of July, the day following the ill-founded and fated rumour of an insurrection in Ireland, and of the disaffection of the troops.

(6) The Red Republican (September 1850)

This sterling democrat who suffered nearly two years' incarceration in Newgate, for advocating the principles of the People's Charter, is about to take a tour through the country and proposes to deliver lectures in all the principal towns. The sufferings of himself and fellow-victims in prison - the principles of democratic and social reform, and the united organisation of democratic and social reformers to obtain the Charter, will form the leading topics of Mr Bezer's lectures... Mr Bezer deserves, and we doubt not will receive, a hearty welcome from the "Reds" in all parts of England... We earnestly solicit our metropolitan friends to give their orders to this persecuted and sterling democrat.

(7) Oxford University and City Herald (3rd April 1852)

The Master Engineers, and their Workmen. Three lectures on the Relationship of Capital and Labour, delivered by, request of the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations at the Marylebone Literary and Scientific Institution, on the 13 th , 20 th and 27 th of February, 1852 by J. M. Ludlow, Esq of Lincoln's Inn, Barrister-at-Law, London; John James Bezer, 183 Fleet Street.