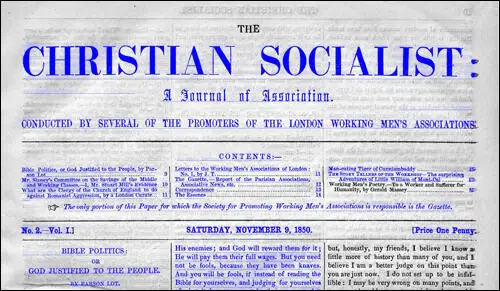

Christian Socialist Journal

On 2nd November, 1850, the Christian Socialist group launched a new journal, Christian Socialist. "On its first page it stated what it was trying to do: "A new idea has gone abroad into the world. That is Socialism, the latest-born of the forces now at work in modern society, and Christianity, the eldest born of those forces, are in their nature not hostile, but akin to each other, or rather that the one is but the development, the outgrowth, the manifestation of the other, so that even the strangest and most monstrous forms of Socialism are at bottom but Christian heresies. That Christianity, however feeble and torpid it may seem to many just now, is truly but as an eagle at moult, shedding its worn-out plumage; that Socialism is but the livery of the nineteenth century (as Protestantism was its livery of the sixteenth) which is now putting on, to spread long its mighty wings for a broader and heavenlier flight. That Socialism without Christianity, on the one hand, is as lifeless as the feathers without the bird, however skillfully the stuffer may dress them up into an artificial semblance of life; and that therefore every socialist system which has endeavoured to stand alone has hitherto in practice either blown up or dissolved away; whilst almost every socialist system which has maintained itself for anytime has endeavoured to stand, or unconsciously to itself has stood, upon those moral grounds of righteous, self-sacrifice, mutual affection, common brotherhood, which Christianity vindicates to itself for an everlasting heritage." (1)

John Ludlow was the editor of this new venture. It was to be a rule of the journal that writers should be anonymous, a common practice of the time. Ludlow's pen-name was John Townsend, or J.T. It was announced in the first edition that the journal would cover the entire spectrum of English life: free trade, education, the land question, poor laws, reform of the law, sanitary reform, taxation, finance, and Church reform. (2)

John Ludlow pointed out in his first editorial: "We do not mean to eschew Politics.We shall have Chartists writing for us, and Conservatives, and yet we hope not to quarrel, having this one common ground of Socialism, just as on the ground we hope not to quarrel, though the professing Christian be mixed in our ranks with those who have hitherto passed for Infidels." (3)

The journal was remarkable value at a penny a copy, for it was about 16,000 words of closely packed material with no paid advertising. It sold around 1,500 copies a week, in spite of its difficulties in finding any distributors to handle it. Brenda Colloms has argued: "Anyone who bought the first copy, and continued to buy it each week would find he had embarked upon an adult education course of a highly specialized nature." (4)

Chartists had been suspicious of Politics for the People and had not read it for that reason, decided that perhaps they should give this middle-class group a chance, and they began to read the Christian Socialist. Many found it to their liking and wrote articles for it. This included Gerald Massey, a genuine people's poet. Massey, the son of a canal boatman, was born in a hut at Gamble Wharf, on 29 May 1828. His father brought up a large family on a weekly wage of some ten shillings. Massey said of himself that he "had no childhood." After a scanty education at the national school at Tring, Massey was when eight years of age put to work at a silk mill. (5)

By 1850 Gerald Massey had moved to London and was working as a freelance journalist. John Ludlow was disturbed that Massey was a follower of George Julian Harney and was a regular contributor to the Red Republican. Ludlow was eager to have Massey write for his paper but made it clear that he had to stop writing for those publications that supported Physical Force Chartism. According to Brenda Colloms: "Massey did not object, for like so many working-class men reared on Nonconformist religious books and ideas, he found the ideas of brotherhood in associations more emotionally satisfying than the cooler and more impersonal socialist dogma." (6)

Another working class agitator who contributed to the Christian Socialist was John James Bezer. He in the past had been one of the leaders of the Chartist movement calling for revolution. On the 26 July 1848 Bezer attended a meeting chaired by John Shaw of the City Lecture Theatre, Milton Street, Cripplegate, where the subject was "Of bringing before the Legislature and the Public the despotic treatment of the Chartist victims." A strong force of police was standing by in case of disturbance. Two days later, at the same venue, Bezer conducted a public meeting condemning the Government's handling of the current problems in Ireland. It was reported that some 1,000 persons mostly Irish were in attendance both inside and outside the hall. Also present were the police and reporters who took notes of what men said at the meeting. (7) Several men at the meeting, including Bezer, George Shell (shoemaker), John Maxwell Bryson (dentist) and Robert Crowe (tailor) were arrested and charged with sedition. (8)

In court it was claimed that Bezer had called on Chartists "to destroy the power of the Queen, and establish a Republic." Bezer was accused of telling people that he would be able to supply 50 fighting men, and that they "were going to get up a bloody revolution". Bezer, Shell, Bryson and Crowe were all found guilty of sedition. According to The Leicestershire Mercury "The jury returned a verdict of guilty; and the other defendants who had been convicted to receive sentence. Mr Baron Platt in passing sentence, addressed them at some length upon their conduct, and told them as the sentence passed upon them at a previous session did not appear to have deterred them, it was clear an increase of severity of punishment must be resorted to: He then sentenced George Smelt, Robert Crowe, and John James Bezer to be imprisoned in the house of correction for two years, to pay a fine of £10 each to the Queen, and at the expiration of their imprisonment to enter into their own recognizances in £100 with two securities of £50 each, to keep the peace for five years." (9)

John James Bezer met John Ludlow and agreed to contribute to the The Christian Socialist. Ten chapters of Bezer's autobiography were published as installments in the journal from 9 August 1851. David Shaw has argued that the autobiography "considering the circumstances, surprisingly well written - record forms both an interesting and an important portrayal, at first hand, of working-class life in Dickensian London." (10)

Soon afterwards John James Bezer met John Bedford Leno at a Christian Socialist meeting. Leno agreed with Bezer that violence between the Chartists and the police was inevitable, and that arms should be carried. Leno later wrote in his autobiography: "In truth, I was for rebellion and civil war, and despaired of ever obtaining justice, or what I then conceived it to be, save by revolution." (11) Leno, who had been apprentice in the printing trade and it was agreed that they should a printers's cooperative, and The Christian Socialist journal became its main customer. (12)

George Julian Harney, a great supporter of John James Bezer, was disgusted by this development. Harney had used his newspaper, The Red Republican to promote Physical Force Chartism. With the help of his friend, Ernest Jones, Harney attempted to use his paper to educate his working class readers about socialism and internationalism. Harney also attempted to convert the trade union movement to socialism. Harney knew that the The Christian Socialist movement was totally opposed to the use of violence and feared that Bezer had "gone over to the enemy". (13)

The journal had a dual purpose. It was a vehicle of Christian Socialist propaganda on the one hand and a "Journal of Association", giving news of current associations and instructions on how to form new ones, on the other. The Christian Socialist became the official mouthpiece of the Christian Socialist movement and resulted in conflict between Frederick Denison Maurice and John Ludlow the editor. Maurice was critical of some of the articles that called for universal suffrage. Ludlow also refused to publish an article by Charles Kingsley on the Bible story of the Canaanites for its incipient racism. (14)

Joseph Millbank and Thomas Shorter, joint secretaries of the Society of Promoters, argued the cooperation was needed to combat poverty in Britain. "We have become rivals where we ought to have become brethren, and have competed with each other when we ought to have cooperated - rivals, with more or less of hate, and hosts of expedients to disguise its hideousness and make it respectable." (15)

The editorship of the The Christian Socialist dominated the life of John Ludlow and he was devastated when it had to stop publication on 28th June 1851 because it was losing too much money. Ludlow and other Christian Socialists now concentrated on publishing pamphlets. However, this caused conflict amongst the leaders. In 1852 Frederick Denison Maurice concluded that the "idea of Christian Socialism were so divergent that only confusion was created when they spoke up." Ludlow agreed and said that different members "had meant different things by the words they used." (16)

Primary Sources

(1) The Christian Socialist (2nd November 1850)

A new idea has gone abroad into the world. That is Socialism, the latest-born of the forces now at work in modern society, and Christianity, the eldest born of those forces, are in their nature not hostile, but akin to each other, or rather that the one is but the development, the outgrowth, the manifestation of the other, so that even the strangest and most monstrous forms of Socialism are at bottom but Christian heresies. That Christianity, however feeble and torpid it may seem to many just now, is truly but as an eagle at moult, shedding its worn-out plumage; that Socialism is but the livery of the nineteenth century (as Protestantism was its livery of the sixteenth) which is now putting on, to spread long its mighty wings for a broader and heavenlier flight. That Socialism without Christianity, on the one hand, is as lifeless as the feathers without the bird, however skilfully the stuffer may dress them up into an artificial semblance of life; and that therefore every socialist system which has endeavoured to stand alone has hitherto in practice either blown up or dissolved away; whilst almost every socialist system which has maintained itself for anytime has endeavoured to stand, or unconsciously to itself has stood, upon those moral grounds of righteous, self-sacrifice, mutual affection, common brotherhood, which Christianity vindicates to itself for an everlasting heritage.

(2) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (9th August 1851)

Six months after my birth, my left eye left me for ever, the small pox, the cause. For two months I was totally blind, and very bad, the "faculty" giving me over for dead more than once. The "faculty" were wrong; I recovered, minus an eye, and often have I been nearly run over through having a "single eye" towards the road; and often have I knocked against a dead wall, and hugged it as if I really loved the dark side of a question. Ah, I've had many a blow through giving half a look at a thing! How many times since I became a costermonger has a policeman hallooed in my ear, "Come! move hon there, vill yer! now go hon, move yer hoff!" while I've actually thought he was on duty in some kitchen with the servant girl, taking care of the house as the master and mistress were out. It was not however so; there he has stood in all his beauty, a Sir Robert Peel's monument�a real one, alive,�and sometimes have I seen him kicking.

My education was very meagre; I learnt more in Newgate than at my Sunday school, but let me not anticipate. Among the many days I shall probably for life remember, is the 21st of December, 1821, when breeched for the first time, and twopence in my bran-new pocket, I proudly marched to Raven Row Sunday School and had my name entered. From that hour, until the hour I finally left, which, with the exception of two intervenings of short duration, lasted nearly fifteen years, I can truly say I loved my school,�no crying when Sunday came round.

I yearned for it; - whether it was because my home was not as it ought to have been, (a painful subject I shall feel bound to say something about in due order,) or because association has ever seemed dear to me, or because I desired to show myself off as an apt scholar, or because I really wanted to learn, or all these causes combined - most certainly I was ever the first to get in to school, and the last to go out.

(3) John James Bezer, The Christian Socialist (16th August 1851)

I ought to have learned a great deal, say you, in fifteen years; well, in the opinion of some, I did, for notwithstanding the disadvantages I laboured under both at home and at school, and there only being six hours a week for me, I rapidly rose from class to class; at seven years old I was in the "testament class" - at eight, in the highest - shortly after, "head boy" - soon after that, "monitor" - at eleven, teacher - and long before I left, head teacher; - and yet, what had I learned? to read well, and that was all. Three years ago I knew nothing of arithmetic, and could scarcely write my own name.

I have just spoken of the disadvantages at school - I shall doubtless displease some of my readers in what I am going to say, but when I commenced this history, I determined that it should be a genuine one, and that I would put down my thoughts without reserve. Now, that school did not even learn me to read; six hours a week, certainly not one hour of useful knowledge; plenty of cant, and what my teachers used to call explaining difficult texts in the Bible, but little, very little else.