Charles Blachford Mansfield

Charles Blachford Mansfield, the son of John Mansfield, rector at Rowner, and Winifred Blachford, was born on 8th May 1819, at Rowner, near Gosport, Hampshire. Charles Mansfield was educated first at a private school at Twyford, and afterwards at Winchester College (1831–5), which he detested. At the age of sixteen his health broke down from what seems to have been poliomyelitis, which left him partially deaf and with a stiff arm. (1)

On 23rd November 1836 he entered his name at Clare College, Cambridge, but was unable to take up residence until October 1839. (2) While at university he became friends with the future novelist, Charles Kingsley. He later described Mansfield as "so wonderfully graceful, active and daring. He was more like an antelope than a man." (3) To compensate for an invalid childhood he had trained himself as a gymnast and used to perform "strange feats" on a gymnastic pole in his room. (4)

Kingsley admitted that "Mansfield was my first love. The first human being, save my mother I ever met who knew what I meant." (5) One biographer, Brenda Colloms, has argued that Mansfield "had a charm of manner which was irresistible… He looked the very pattern of the blond, handsome young Englishman of good family. He was slim and athletic, and an amusing and informative conversationist, and to outsiders he must have seemed a young man with everything to live for. His friends knew a different Mansfield, a sensitive soul who had barely survived the iron rule of the schoolmasters and the brutal tyranny of the boys at Winchester College and had been removed from school at sixteen suffering from a nervous breakdown." (6)

Scientific Research

On 3rd February 1842 he secretly married a widow, Catherine Shafto, daughter of a London merchant, William Warne Higgs. She was constantly unfaithful to him and eventually eloped to Australia. (7) He was never able to divorce her and had many love affairs. Owing to frequent absences due to ill health, and intellectual and social diversions he did not graduate BA until 1846. (8)

Mansfield considered becoming a doctor and while still at Cambridge he attended the classes at St. George's Hospital. Mansfield was convinced of the efficacy of Mesmerism. His theory was that by making passes before the eyes of his patient he could hypnotise him and restore his "animal magnetism". Mansfield also became a vegetarian and teetotaller for health reasons. (9)

When he settled in London in 1846 he definitely devoted himself to chemistry. In 1848, after completing the chemistry course at the Royal College, he undertook a series of experiments which resulted in "one of the most valuable of recent gifts to practical chemistry, the extraction of benzol from coal-tar, a discovery which laid the foundation of the aniline industry. Mansfield patented his inventions, then an expensive process, but others reaped the profits. He later published a pamphlet, Benzole, its Nature and its Utility, to indicate what he foresaw as some of the most important applications of benzene. These included perfuming soaps, urban illumination, surgical plasters, and dry-cleaning. (10)

Christian Socialism

His friend, Charles Kingsley, was now rector of Eversley Church. He was also becoming very interested in politics. On 10th April, 1848, a group of Christians who supported Chartism held a meeting in London. People who attended the meeting included Kingsley, Frederick Denison Maurice, John Ludlow and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class. (11)

Feargus O'Connor had been vicious attacks on other Chartist leaders such as William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, Bronterre O'Brien and Henry Vincent who advocated Moral Force. O'Connor questioned this strategy and began to make speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor became the leader of what became known as the Physical Force Chartists, Disturbed by these events members of the Christian Socialist movement volunteered to become special constables at these demonstrations. (12) John Ludlow later wrote: "The present generation has no idea of the terrorism which was at that time exercised by the Chartists." (13)

In April 1849, Charles Kingsley wrote to his wife about the plan to publish a political newspaper. "I really cannot go home this afternoon. I have spent it with Archdeacon Hare, and Parker, starting a new periodical, a Penny People's Friend, in which Maurice, Hare, Ludlow, Mansfield, and I are going to set to work to supply the place of the defunct Saturday Magazine. I send you my first placard. Maurice is delighted with it. I cannot tell you the interest which it has excited with everyone who has seen it.... I have got already £2.10.0 towards bringing out more, and Maurice is subscription hunting for me." (14)

The following month Charles Mansfield, Charles Kingsley, Frederick Denison Maurice, Thomas Hughes, and John Ludlow began publishing a penny journal, Politics for the People, and this was considered the starting-point of the Christian Socialist movement. It was "sympathetic to the poor and based upon the acknowledgment that God rules in human society... They addressed themselves to workmen. They confessed that they were not workmen, but asked for workmen's help in bridging the gulf that divided them". (15)

Mansfield's theology was based more on a rationalist concept of a Divine Idea than on a clear Christian faith. When his father heard of his involvement in the Christian Socialist movement he immediately cut his allowance, and Mansfield adopted the vegetarian diet and simple lifestyle for which he became renowned. However, it had a serious impact on his ability to finance the group's publishing ventures. (15a)

By this time Charles Mansfield had joined the Christian Socialist movement and was involved in their efforts at social reform among the workmen of London, and in the cholera year helped to provide pure water for districts like Bermondsey. He also wrote several papers in Politics for the People, Mansfield, who often wrote about birds, adopted the pseudonym Will Willow-wren. Mansfield agreed with other members of the group that the essays were designed to help the working man escape from "dull bricks and mortar and the ugly colourless things which fill the workshop and the factory." (16)

The journal was selling at about 2,000 copies an edition. (17) Kingsley wrote several articles for the journal. He took the signature ‘Parson Lot,' on account of a discussion with his friends, in which, being in a minority of one, he had said that he felt like Lot, "when he seemed as one that mocked to his sons-in-law." (18)

During the summer of 1848, Charles Mansfield, Charles Kingsley, Thomas Hughes and John Ludlow would have editorial meetings at the house of Frederick Denison Maurice. Important socialists of the day, including Robert Owen, the owner of the New Lanark Mills and Thomas Cooper, one of the leaders of the Chartist movement, sometimes took part in these discussions. (19)

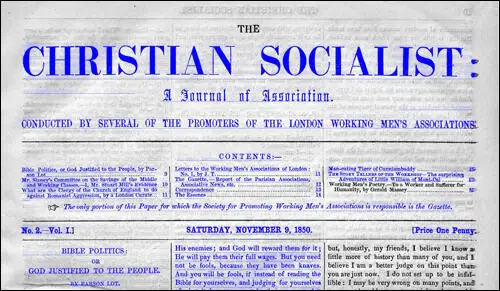

Politics for the People was an expensive journal to produce and by July 1848, after seventeen editions, the decision was taken to stop publication. It was replaced by Christian Socialist, which appeared from 2nd November, 1850 to 28th June 1851. The journal that covered every topic imaginable within the field of national and ecclesiastical politics and preached the message of national and ecclesiastical politics and preached the message of socialism through articles by all the major member of the group. (20)

Mansfield, who often wrote about birds, adopted the pseudonym Will Willow-wren. Mansfield agreed with other members of the group that the essays were designed to help the working man escape from "dull bricks and mortar and the ugly colourless things which fill the workshop and the factory." (21)

In September 1850 the description of a balloon machine constructed at Paris led Mansfield to investigate the whole problem of aeronautics, and in the next few months he wrote his Aerial Navigation, still after forty years one of the most striking and suggestive works on its subject. In the winter of 1851–2 he delivered in the Royal Institution a course of lectures on the chemistry of the metals, remarkable for some brilliant generalisations and for an attempted classification upon a principle of his own represented by a system of triangles (22)

Mansfield was generous with his friends. Charles Kingsley wrote to John Ludlow about his financial problems: "Can you as a lawyer, as well as a friend, tell me of any means of borrowing £500 for, say, five years, at reasonable interest. By that time either my books may be selling well, or my house may have stopped falling about my ears, or - or God may think we have suffered enough. My father would, but cannot help me, and therefore I dare not ask him: and as for certain rich connections of mine, I would die sooner than ask them, who tried to prevent my marriage because forsooth I was poor." (23)

Mansfield suggested lending Kingsley £140 which was all he had, and promising the balance of the £500 in the near future. Ludlow, however, knowing Kingsley's pride, drew up a document in which the creditor appeared as H. N. Turnstiles. "Eventually," wrote Ludlow, "Mrs Kingsley twigged the trick, and there was a grand scene (of gratitude) though I am not sure that Kingsley quite relished my having been the means of humbugging him." (24)

Paraguay

In the summer of 1852 Mansfield started for Paraguay, partly "to gratify a whim of wishing to see the country, which I believed to be an unspoiled Arcadia". (25) Another reason was to escape a sexual entanglement with a working-class woman that had shocked his Christian socialist friends. He was told by Charles Kingsley that her presence at his home in Eversley would not be welcomed. (26)

Mansfield arrived at Buenos Aires in August, and then sailed up the River Paraná, and reached Asunción on 24th November, where he remained two and a half months. Paraguay, under José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia and his successor Carlos Antonio Lopez, had been shut off from the world for forty years, and Mansfield was probably the first English visitor to the capital. "His letters, published after his death, contained bright and careful descriptions of Paraguayan society, the scenery, plant and bird life, and a scheme for the colonization of the Gran Chaco, a dream that remained with him for the remainder of his life." (27)

Death

Mansfield returned to England in the spring of 1853, resumed his chemical studies, and began a work on the constitution of salts, based on the lectures delivered two years previously at the Royal Institution. This work, the Theory of Salts: A Treatise on the Constitution of Bipolar Chemical Compounds, his most important contribution to theoretical chemistry, he finished in 1855, and placed in a publisher's hands. (28)

Mansfield had meanwhile been invited to send specimens of benzol to the Paris Exhibition. In 1855 he hired rooms in St. John's Wood and engaged an assistant and began the laborious process of preparing his samples. "The pair worked long hours during a cold, snowy February, watching over the hot, fume-laden apparatus, often exhausted but buoyed up by anticipation of success at the Exhibition." (29)

On 17th February 1855, the naphtha boiled over and caught light with the risk of an explosion at any moment. Mansfield seized the burning still in his arms, intending to carry it into the street, but the door jammed, imprisoning him in the room. By the time he managed to push it out of the window both he and his assistant were badly burned. They scrambled out of the window and dropped to the snow-covered pavement. Both men rolled in the snow to smother the flames. They were taken to Middlesex Hospital but Mansfield lingered for nine agonizing days, his friends taking it in turns to sit by his bedside. (30)

Charles Blachford Mansfield was buried in Weybridge churchyard. His tragic death, with so many of his talents unfulfilled, affected his friends emotionally for several years to come. Even in death his private life continued to embarrass them, for Mansfield left his fortune to a former lover, a Mrs Burrows, née Gardiner, even though she had subsequently married another man; she declined the bequest. (31)

Charles Kingsley was too distressed by Mansfield's death to attend his funeral. He wrote to John Ludlow: "To him and to Frank Penrose what do I not owe. They were the only two heroic souls I met during those dark Cambridge years. They alone kept me from sinking into the mire and drowning like a dog. And now one is gone and I shall cling all the more to the other." (32)

Primary Sources

(1) Brenda Colloms, Victorian Visionaries (1982)

Charles Mansfield, who was certainly as uncompromising and eccentric as the rest, perhaps, more so, but he had a charm of manner which was irresistible… He looked the very pattern of the blond, handsome young Englishman of good family. He was slim and athletic, and an amusing and informative conversationist, and to outsiders he must have seemed a young man with everything to live for. His friends knew a different Mansfield, a sensitive soul who had barely survived the iron rule of the schoolmasters and the brutal tyranny of the boys at Winchester College and had been removed from school at sixteen suffering from a nervous breakdown. His father was a wealthy, worldly Hampshire rector who made no allowances for his gifted but unusual son. In 1839 Mansfield's inventive fancy was as poetic in his world of science as was Kingsley's in the world of language, and like Kingsley, he enjoyed the freedom of the university although he was a martyr to depression and frequently overcome by feelings of guilt.