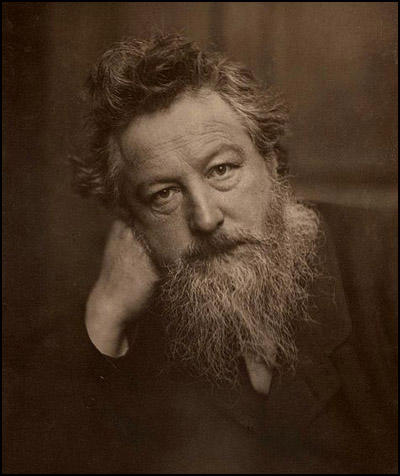

William Morris

William Morris, the son of a successful businessman, was born in Walthamstow, a quiet village east of London, on 24th March, 1834. After successfully investing in a copper mine, William's father was able to purchase Woodford Hall, a large estate on the edge of Epping Forest, in 1840.

Morris was educated at Marborough and Exeter College. At Oxford University Morris met Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The three men were all artists and formed a group called the Brotherhood. During this period their work was inspired by the history, ritual and architecture of the Medieval period. Morris and Burne-Jones were committed Anglicans and for a time they talked of taking part in a "crusade and holy warfare" against the art and culture of their own time.

Burne-Jones later recalled: "When I first knew Morris nothing would content him but being a monk, and getting to Rome, and then he must be an architect, and apprenticed himself to Street, and worked for two years, but when I came to London and began to paint he threw it all up, and must paint too, and then he must give it up and make poems, and then he must give it up and make window hangings and pretty things, and when he had achieved that, he must be a poet again, and then after two or three years of Earthly Paradise time, he must learn dyeing, and lived in a vat, and learned weaving, and knew all about looms, and then made more books, and learned tapestry, and then wanted to smash everything up and begin the world anew, and now it is printing he cares for, and to make wonderful rich-looking books - and all things he does splendidly - and if he lives the printing will have an end - but not I hope, before Chaucer and the Morte d'Arthur are done; then he'll do I don't know what, but every minute will be alive."

Members of the Brotherhood were influenced by the writings of the art critic, John Ruskin, who praised the art of medieval craftsmen, sculptors and carvers who he believed were free to express their creative individualism. Ruskin was also very critical of the artists of the 19th century, who he accused of being servants of the industrial age. David Meakin has argued: "A rebel against his own time, he was yet deeply of his time, deeply Victorian, and this is only one of the many fertile paradoxes that make his manifold activity so fascinating."

In 1857 Morris joined with Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti to paint frescoes for the Oxford Union. He also began writing poetry and in 1858 his book The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems was published. Morris wrote: "With the arrogance of youth, I determined to do no less than to transform the world with Beauty. If I have succeeded in some small way, if only in one small corner of the world, amongst the men and women I love, then I shall count myself blessed, and blessed, and blessed, and the work goes on."

Morris and his Pre-Raphaelite friends formed their own company of designers and decorators. As well as Burne-Jones and Rossetti, the group now included the architect Philip Webb and Ford Madox Brown. Morris, Marshall, Faulkener & Co, specialized in producing stained glass, carving, furniture, wallpaper, carpets and tapestries. The company's designs brought about a complete revolution in public taste. Their commissions included the Red House in Upton (1859), the Armoury and Tapestry Room in St. James's Palace (1866) and the Dining Room in the Victoria and Albert Museum (1867). In 1875 the partnership came to an end and Morris formed a new business called Morris & Company.

Despite the large number of commissions that he received, William Morris continued to find time to write poetry and prose. His work during this period included The Life and Death of Jason (1867), The Earthly Paradise (1868) and the Volksunga Saga (1870). In one article Morris argued: "So long as the system of competition in the production and exchange of the means of life goes on, the degradation of the arts will go on; and if that system is to last for ever, then art is doomed, and will surely die; that is to say, civilization will die."

The art critic, Patrick Conner, has argued that the writings of John Ruskin inspired artists such as Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: "Ruskin... proved an inspiration to William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, whose enthusiasm carried Pre-Raphaelite principles into many branches of the decorative arts. They inherited from Ruskin a hostility to classical and Renaissance culture which extended to the arts and design of their own time. Ruskin and his followers believed that the nineteenth century was still afflicted by a demand for mass-production... They opposed themselves to mechanized production, meaningless ornament and anonymous architecture of cast iron and plate glass."

In the 1870s Morris became upset by the aggressive foreign policy of the Conservative Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. In began writing to newspapers and publishing pamphlets where he attacked Disraeli and supported the anti-imperialism of the Liberal Party leader, William Gladstone. However, he became disillusioned with Gladstone's Liberal Government that gained power after the 1880 General Election and by 1883 Morris had become a socialist. Morris later explained his new political philosophy: "What I mean by Socialism is a condition of society in which there should be neither rich nor poor, neither master nor master's man, neither idle nor overworked, neither brainslack brain workers, nor heartsick hand workers, in a word, in which all men would be living in equality of condition, and would manage their affairs unwastefully, and with the full consciousness that harm to one would mean harm to all - the realisation at last of the meaning of the word commonwealth."

Morris joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and began contributing articles to its journal Justice. However, Morris was soon in dispute with the party leader, H. H. Hyndman. Morris shared Hyndman's Marxist beliefs, but objected to Hyndman's nationalism and the dictatorial methods he used to run the party.

In December, 1884, Morris left the SDF and along with Walter Crane, Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling formed the Socialist League. Strongly influenced by the ideas of William Morris, the party published a manifesto where it advocated revolutionary international socialism. Morris was also the main contributor the the party's journal, Commonweal.

Over the next few years Morris wrote socialist pamphlets, sold socialist literature on street corners, went on speaking tours, encouraged and participated in strikes and took part in several political demonstrations. In July, 1887 Morris was arrested after a demonstration in London. Four months later he participated in what became known as Bloody Sunday, when three people were killed and 200 injured during a public meeting in Trafalgar Square. The following week, a friend, Alfred Linnell, was fatally injured during another protest demonstration and this event resulted in Morris writing, Death Song.

Morris devoted a lot of his time to political writing. This included Chants for Socialists (1883), The Pilgrims of Hope(1885) and the Dream of John Ball (1888). The following year Morris wrote one of his most important books, News from Nowhere. The book, a Utopian fantasy, tells the story of a man who falls asleep after an evening at a Socialist League meeting. He wakes in the future to find England transformed into a communist paradise where men and women are free, healthy, and equal. Money, prisons, schools and government have been abolished and the industrial squalor of England in the 1880s has disappeared. At the close of the book, the man has returned to the present, but has been inspired by what he has seen and his determined to work for a socialist future.

It has been argued by David Meakin that Morris was not a very successful politician: "Morris had little talent for politicking, and the intransigence of the Socialist League tended to cut it off from parliamentary politics. He feared and denounced the tendency for socialism to sink into compromise and palliatory reform, offensive to his total ethical vision. Only in his final years, uncompromisingly styling himself a communist, did he come to accept the educative value of local struggles, whilst always insisting that these should be catalysts for total change."

Henry Snell met Morris during this period: "It was William Morris who first made me consciously aware of the ugliness of a society which so arranged its affairs that its workers were deprived of the beauty which life should give. I remember him as a bluff, vital, and challenging personality, whose influence upon those who knew him was both marked and lasting. I knew Morris only as a humble and admiring devotee may know the master. In my mind his gifts and experience placed him among the supermen. I might have known him better if I had been less aware of his greatness." Bruce Glasier has argued: "William Morris was to my mind one of the greatest men of genius this or any other land has ever known."

Margaret McMillan was another young socialist who was impressed with Morris: "We were invited to meet William Morris at Kelmscott House. Mr. Morris received us with patient cordiality. Dressed in navy blue, and with his hair much ruffled, he looked like a sea captain receiving guests on a stormy day, but glad to see them. He wanted to hear about his Edinburgh friends, especially John Glasse, with whom he could discuss handloom weaving as well as literature or Socialism. He lighted his pipe and talked, sitting upright in a high chair. We listened to his copious, glittering talk. Morris belonged to a rich, radiant, present world. He created it. He was practical as well as impatient." W. B. Yeats has pointed out: "No man I have ever known was so well loved. He was looked up to as to some worshipped medieval king. People loved him as children are loved. I soon discovered his spontaneity and joy and made him my chief of men."

In 1891 William Morris became seriously ill with kidney disease. He continued to write on socialism and occasionally was fit enough to give speeches at public meetings. Morris political views had been influenced by the anarchist theories of Peter Kropotkin. Morris was also sympathetic to syndicalism of Tom Mann. Although Morris supported trustworthy socialist politicians such as George Lansbury and Keir Hardie, he believed that socialism would be achieved through trade union activity rather than by getting socialists elected to the House of Commons.

In his last few years of his life Morris wrote Socialism, Its Growth and Outcome (1893), Manifesto of English Socialists (1893) The Wood Beyond the World (1894) and Well at the World's End (1896).

William Morris died on 3rd October, 1896.

Primary Sources

(1) William Morris, Art, Wealth and Riches (1883)

I will, with your leave, tell the chief things which I really I want to see changed, lest I should seem to have nothing to bid you to but destruction, the destruction of a system by some thought to have been made to last for ever. I want, then, all persons to be educated according to their capacity, not according to the amount of money which their parents happen to have. I want all persons to have manners and breeding according to their innate goodness and kindness, and not according to the amount of money which their parents happen to have. As a consequence of these two things I want to be able to talk to any of my countrymen in his own tongue freely, and feeling sure that he will be able to understand my thoughts according to his innate capacity; and I also want to be able to sit at table with a person of any occupation without a feeling of awkwardness and constraint being present between us. I want no one to have any money except as due wages for work done; and, since I feel sure that those who do the most useful work will neither ask nor get the highest wages, I believe that this change will destroy that worship of a man for the sake of his money, which everybody admits is degrading, but which very few indeed can help sharing in. I want those who do the rough work of the world - sailors, miners, ploughmen, and the like - to be treated with consideration and respect, to be paid abundant money-wages, and to have plenty of leisure. I want modern science, which I believe to be capable of overcoming all material difficulties, to turn from such preposterous follies as the invention of anthracine colours and monster cannon to the invention of machines for performing such labour as is revolting and destructive of self-respect to the men who now have to do it by hand. I want handicraftsmen proper, that is, those who make wares, to be in such a position that they may be able to refuse to make foolish and useless wares, or to make the cheap and nasty wares which are the mainstay of competitive commerce, and are indeed slave-wares, made by and for slaves. And in order that the workmen may be in this position, I want division of labour restricted within reasonable limits, and men taught to think over their work and take pleasure in it. I also want the wasteful system of middlemen restricted, so that workmen may be brought into contact with the public, who will thus learn something about their work, and so be able to give them due reward of praise for excellence.

(2) William Morris, Art and Socialism (1884)

Nothing should be made by man's labour which is not worth making; or which must be made by labour degrading to the makers. Simple as that proposition is, and obviously right as I am sure it must seem to you, you will find, when you come to consider the matter, that it is a direct challenge to the death to the present system of labour in civilized countries. That system, which I have called competitive Commerce, is distinctly a system of war; that is of waste and destruction: or you may call it gambling if you will, the point of it being that under it whatever a man gains he gains at the expense of some other man's loss. Such a system does not and cannot heed whether the matters it makes are worth making; it does not and cannot heed whether those who make them are degraded by their work: it heeds one thing and only one, namely, what it calls making a profit; which word has got to be used so conventionally that I must explain to you what it really means, to wit the plunder of the weak by the strong! Now I say of this system, that it is of its very nature destructive of Art, that is to say of the happiness of life. Whatever consideration is shown for the life of the people in these days, whatever is done which is worth doing, is done in spite of the system and in the teeth of its maxims; and most true it is that we do, all of us, tacitly at least, admit that it is opposed to all the highest aspirations of mankind.

Do we not know, for instance, how those men of genius work who are the salt of the earth, without whom the corruption of society would long ago have become unendurable? The poet, the artist, the man of science, is it not true that in their fresh and glorious days, when they are in the heyday of their faith and enthusiasm, they are thwarted at every turn by Commercial war, with its sneering question 'Will it pay?' Is it not true that when they begin to win worldly success, when they become comparatively rich, in spite of ourselves they seem to us tainted by the contact with the commercial world?

Need I speak of great schemes that hang about neglected; of things most necessary to be done, and so confessed by all men, that no one can seriously set a hand to because of the lack of money; while if it be a question of creating or stimulating some foolish whim in the public mind, the satisfaction of which will breed a profit, the money will come in by the ton? Nay, you know what an old story it is of the wars bred by Commerce in search of new markets, which not even the most peaceable of statesmen can resist; an old story and still it seems for ever new, and now become a kind of grim joke, at which I would rather not laugh if I could help it, but am even forced to laugh from a soul laden with anger.

That is what three centuries of Commerce have brought that hope to which sprang up when feudalism began to fall to pieces. What can give us the day-spring of a new hope? What, save general revolt against the tyranny of Commercial war? The palliatives over which many worthy people are busying themselves now are useless: because they are but unorganized partial revolts against a vast widespreading grasping organization which will, with the unconscious instinct of a plant, meet every attempt at bettering the condition of the people with an attack on a fresh side; new machines, new markets, wholesale emigration, the revival of grovelling superstitions, preachments of thrift to lack-alls, of temperance to the wretched; such things as these will baffle at every turn all partial revolts against the monster we of the middle classes have created for our own undoing.

(3) William Morris, Commonweal (30th November 1884)

Take courage, and believe that we of this age, in spite of all its torment and disorder, have been born to a wonderful heritage fashioned of the work of those that have gone before us; and that the day of the organization of man is dawning. It is not we who can build up the new social order; the past ages have done the most of that work for us; but we can clear our eyes to the signs of the times, and we shall then see that the attainment of a good condition of life is being made possible for us, and that it is now our business to stretch out our hands and take it.

And how? Chiefly, I think, by educating people to a sense of their real capacities as men, so that they may be able to use to their own good the political power which is rapidly being thrust upon them; to get them to see that the old system of organizing labour for individual profit is becoming unmanageable, and that the whole people have now got to choose between the confusion resulting from the breakup of that system and the determination to take in hand the labour now organized for profit, and use its organization for the livelihood of the community: to get people to see that individual profit-makers are not a necessity for labour but an obstruction to it, and that not only or chiefly because they are the perpetual pensioners of labour, as they are, but rather because of the waste which their existence as a class necessitates. All this we have to teach people, when we have taught ourselves; and I admit that the work is long and burdensome; as I began by saying, people have been made so timorous of change by the terror of starvation that even the unluckiest of them are stolid and hard to move. Hard as the work is, however, its reward is not doubtful. The mere fact that a body of men, however small, are banded together as Socialist missionaries shows that the change is going on. As the working classes, the real organic part of society, take in these ideas, hope will arise in them, and they will claim changes in society, many of which doubtless will not tend directly towards their emancipation, because they will be claimed without due knowledge of the one thing necessary to claim, equality of condition; but which indirectly will help to break up our rotten sham society, while that claim for equality of condition will be made constantly and with growing loudness till it must be listened to, and then at last it will only be a step over the border, and the civilized world will be socialized; and, looking back on what has been, we shall be astonished to think of how long we submitted to live as we live now.

(4) William Morris, Socialist League pamphlet (30th November 1885)

The misery and squalor which we people of civilization bear with so much complacency as a necessary part of the manufacturing system, is just as necessary to the community at large as a proportionate amount of filth would be in the house of a private rich man. If such a man were to allow the cinders to be raked all over his drawing-room, and a privy to be established in each corner of his dining room, if he habitually made a dust and refuse heap of his once beautiful garden, never washed his sheets or changed his tablecloth, and made his family sleep five in a bed, he would surely find himself in the claws of a commission de lunatico. But such acts of miserly folly are just what our present society is doing daily under the compulsion of a supposed necessity, which is nothing short of madness.

(5) William Morris, Communism (1893)

Intelligence enough to conceive, courage enough to will, power enough to compel. If our ideas of a new society are anything more than a dream, these three qualities must animate the due effective majority of the working people; and then, I say, the thing will be done.

(6) William Morris, Justice (1st May, 1896)

The capitalist classes are doubtless alarmed at the spread of Socialism all over the civilized world. They have at least an instinct of danger; but with that instinct comes the other one of self-defence. Look how the whole capitalist world is stretching out long arms towards the barbarous world and grabbing and clutching in eager competition at countries whose inhabitants don't want them; nay, in many cases, would rather die in battle, like the valiant men they are, than have them. So perverse are these wild men before the blessings of civilization which would do nothing worse for them (and also nothing better) than reduce them to a propertyless proletariat.

And what is all this for? For the spread of abstract ideas of civilization, for pure benevolence, for the honour and glory of conquest? Not at all. It is for the opening of fresh markets to take in all the fresh profit-producing wealth which is growing greater and greater every day; in other words, to make fresh opportunities for waste; the waste of our labour and our lives.

And I say this is an irresistible instinct on the part of the capitalists, an impulse like hunger, and I believe that it can only be met by another hunger, the hunger for freedom and fair play for all, both people and peoples. Anything less than that the capitalist powers will brush aside. But that they cannot; for what will it mean? The most important part of their machinery, the 'hands' becoming MEN, and saying, 'Now at last we will it; we will produce no more for profit but for use, for happiness, for LIFE.'

(7) In a book published in 1927, Margaret McMillan wrote about the different socialist leaders she met in her youth. This included William Morris.

We were invited to meet William Morris at Kelmscott House. Mr. Morris received us with patient cordiality. Dressed in navy blue, and with his hair much ruffled, he looked like a sea captain receiving guests on a stormy day, but glad to see them. He wanted to hear about his Edinburgh friends, especially John Glasse, with whom he could discuss handloom weaving as well as literature or Socialism. He lighted his pipe and talked, sitting upright in a high chair. We listened to his copious, glittering talk. Morris belonged to a rich, radiant, present world. He created it. He was practical as well as impatient.

(8) Walter Crane, On the Death of William Morris (1896)

How can it be! that strong and fruitful life

Hath ceased - that strenuous but joyful heart,

Skilled craftesman in the loom of song and art,

Whose voice by beating seas of hope and strife,

Would lift the soul of labour from the knife,

And strive against greed of factory and mart -

Ah! ere the morning, must he, too, depart

While yet with battle cries the air is rife?

Blazon the name in England's Book of Gold

Who loved her, and who wrought her legends fair,

Woven in song and written in design,

The wonders of the press and loom - a shrine,

Beyond the touch of death, that shall enfold

In life's House Beautiful, a spirit rare.

(9) Bruce Glasier, William Morris and the Early Days of the Socialist Movement (1921)

William Morris was to my mind one of the greatest men of genius this or any other land has ever known.

(10) Henry Snell, Men Movements and Myself (1936)

It was William Morris who first made me consciously aware of the ugliness of a society which so arranged its affairs that its workers were deprived of the beauty which life should give. I remember him as a bluff, vital, and challenging personality, whose influence upon those who knew him was both marked and lasting. I knew Morris only as a humble and admiring devotee may know the master. In my mind his gifts and experience placed him among the supermen. I might have known him better if I had been less aware of his greatness.

(11) W. B. Yeats, Autobiography (1955)

No man I have ever known was so well loved. He was looked up to as to some worshipped medieval king. People loved him as children are loved. I soon discovered his spontaneity and joy and made him my chief of men.