Bloody Sunday

The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) organised a meeting for 13th November, 1887 in Trafalgar Square to protest against the policies of the Conservative Government headed by the Marquess of Salisbury. Sir Charles Warren, the head of the Metropolitan Police wrote to Herbert Matthews, the Home Secretary: "We have in the last month been in greater danger from the disorganized attacks on property by the rough and criminal elements than we have been in London for many years past. The language used by speakers at the various meetings has been more frank and open in recommending the poorer classes to help themselves from the wealth of the affluent." As a result of this letter, the government decided to ban the meeting and the police were given the orders to stop the marchers entering Trafalgar Square.

Henry Hamilton Fyfe was one of the special constables on duty that day: "When the unemployed dockers marched on Trafalgar Square, where meetings were then forbidden, I enrolled myself as a special constable to defend the classes against the masses. The dockers striking for their sixpence an hour were for me the great unwashed of music-hall and pantomime songs. Wearing an armlet and wielding a baton, I paraded and patrolled and felt proud of myself."

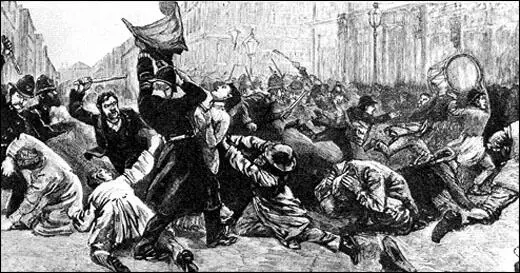

The SDF decided to continue with their planned meeting with Henry M. Hyndman, John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham being the three main speakers. Edward Carpenter explained what happened next: "The three leading members of the SDF - Hyndman, Burns and Cunninghame Graham - agreed to march up arm-in-arm and force their way if possible into the charmed circle. Somehow Hyndman was lost in the crowd on the way to the battle, but Graham and Burns pushed their way through, challenged the forces of Law and Order, came to blows, and were duly mauled by the police, arrested, and locked up. I was in the Square at the time. The crowd was a most good-humoured, easy going, smiling crowd; but presently it was transformed. A regiment of mounted police came cantering up. The order had gone forth that we were to be kept moving. To keep a crowd moving is I believe a technical term for the process of riding roughshod in all directions, scattering, frightening and batoning the people."

Walter Crane was one of those who witnessed this attack: "I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life - only the attack was all on one side. The police, in spite of their numbers, apparently thought they could not cope with the crowd. They had certainly exasperated them, and could not disperse them, as after every charge - and some of these drove the people right against the shutters in the shops in the Strand - they returned again."

The Times took a different view of this event: "It was no enthusiasm for free speech, no reasoned belief in the innocence of Mr O'Brien, no serious conviction of any kind, and no honest purpose that animated these howling toughs. It was simple love of disorder, hope of plunder it may be hoped that the magistrates will not fail to pass exemplary sentences upon those now in custody who have laboured to the best of their ability to convert an English Sunday into a carnival of blood."

George Barnes was one of those who was badly injured by the charging police horses. Some of the protesters were arrested and later two of the leaders of the march, John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham, were arrested and later sentenced to a six-week prison sentence.

Primary Sources

(1) Sir Charles Warren, head of the Metropolitan Police, sent a letter to Herbert Matthews, the Home Secretary calling for 20,000 special constables to deal with socialist meetings in London (22nd October, 1887)

We have in the last month been in greater danger from the disorganized attacks on property by the rough and criminal elements than we have been in London for many years past. The language used by speakers at the various meetings has been more frank and open in recommending the poorer classes to help themselves from the wealth of the affluent.

(2) Walter Crane later described what took place on Bloody Sunday on 13th November 1887.

I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life - only the attack was all on one side. The police, in spite of their numbers, apparently thought they could not cope with the crowd. They had certainly exasperated them, and could not disperse them, as after every charge - and some of these drove the people right against the shutters in the shops in the Strand - they returned again.

(3) Edward Carpenter, My Days and Dreams (1916)

A socialist meeting had been announced for 3 p.m. in Trafalgar Square, the authorities, probably thinking Socialism a much greater terror than it really was, had vetoed the meeting and drawn a ring of police, two deep, all round the interior part of the Square.

The three leading members of the SDF - Hyndman, Burns and Cunninghame Graham - agreed to march up arm-in-arm and force their way if possible into the charmed circle. Somehow Hyndman was lost in the crowd on the way to the battle, but Graham and Burns pushed their way through, challenged the forces of "Law and Order", came to blows, and were duly mauled by the police, arrested, and locked up.

I was in the Square at the time. The crowd was a most good-humoured, easy going, smiling crowd; but presently it was transformed. A regiment of mounted police came cantering up. The order had gone forth that we were to be kept moving. To keep a crowd moving is I believe a technical term for the process of riding roughshod in all directions, scattering, frightening and batoning the people.

I saw my friend Robert Muirhead seized by the collar by a mounted man and dragged along, apparently towards a police station, while a bobby on foot aided in the arrest. I jumped to the rescue and slanged the two constables, for which I got a whack on the cheek-bone from a baton, but Muirhead was released.

The case came into Court afterwards, and Burns and Graham were sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment, each for "unlawful assembly". I was asked to give evidence in favour of the defendants, and gladly consented - though I had not much to say, except to testify to the peaceable character of the crowd and the high-handed action of the police. In cross-examination I was asked whether I had not seen any rioting; and when I replied in a very pointed way "Not on the part of the people!" a large smile went round the Court, and I was not plied with any more questions.

(4) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

Angry Labour leaders announced that, on Sunday, November 13th, 1887, Trafalgar Square would be stormed. Squadrons of military, fully armed, and powerful detachments of police, were drafted there to resist any such attempt. On the appointed day, workers led by Burns and others tried to force a way through the armed ranks, to demonstrate the rights of free speech. Bricks and stones were flung, iron railings crashed on sabres and bayonets, dozens of workmen were wounded, and the attack was beaten off. Burns and others were arrested.

A month or two later, another effort was made to storm the Square, and a workman was killed. Burns made a speech at the funeral, and was again arrested. At his trial at the Old Bailey, H. H. Asquith was Counsel for the Defence. Burns was sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment; later, he and Asquith were Cabinet Ministers together.

(5) The Times (14th November, 1887)

It was no enthusiasm for free speech, no reasoned belief in the innocence of Mr O'Brien, no serious conviction of any kind, and no honest purpose that animated these howling toughs. It was simple love of disorder, hope of plunder it may be hoped that the magistrates will not fail to pass exemplary sentences upon those now in custody who have laboured to the best of their ability to convert an English Sunday into a carnival of blood.

(6) Henry Hamilton Fyfe, My Seven Selves (1935)

When the unemployed dockers marched on Trafalgar Square, where meetings were then forbidden, I enrolled myself as a special constable to defend the classes against the masses. The dockers striking for their sixpence an hour were for me "the great unwashed" of music-hall and pantomime songs. Wearing an armlet and wielding a baton, I paraded and patrolled and felt proud of myself.

My old gentleman (his boss at The Times newspaper) at the office was a Tory of uncompromising violence. He would have had the unemployed shot down. He thought that Gladstone, the Liberal leader, was literally possessed of a devil.