Social Democratic Federation

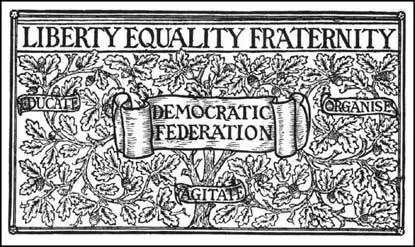

While on holiday in the United States in 1881, Henry M. Hyndman read a copy of Karl Marx's Das Capital. Hyndman was deeply influenced by the book and decided to become active in politics when he arrived back in England. The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) became the first Marxist political group in Britain and over the next few months Hyndman was able to recruit trade unionists such as Tom Mann and John Burns into the organisation. Eleanor Marx, Karl's youngest daughter became a member, and so did the artist and poet, William Morris. Other members included George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, Henry H. Champion, Theodore Rothstein, Helen Taylor, John Scurr, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Frank Harris, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillett. Hyndman became editor of the SDF's newspaper, Justice.

Paul Thompson argues in his book, Socialist, Liberals and Labour (1967) that it was the publication of the book, Progress and Povery by Henry George that increased the popularity of the SDF: "The real socialist revival was set off by Henry George, the American land reformer, whose English campaign tour of 1882 seemed to kindle the smouldering unease with narrow radicalism. This radical voice from the Far West of America, a land of boundless promise, where, if anywhere, it might seem that freedom and material progress were secure possessions of honest labour, announced grinding poverty, the squalor of congested city life, unemployment, and utter helplessness." By 1885 the organisation had over 700 members.

Ben Tillett was very impressed by H. M. Hyndman: "H. M. Hyndman was an arrogant intellectual possessing a mind, forensic, exact and ruthless, with a patience and a capacity for details devastating to an opponent. He was in many ways our chief intellectual prize. He seemed to us a mental giant. He was a schoolmaster and teacher, but he lacked the softer human quality which senses the needs as well as the weakness of humanity. In debate, he brooked but little discussion and no opposition at all. He failed specifically because of this intellectual attitude."

Bruce Glasier had doubts about Hyndman's approach to politics: "Racy, argumentative, declamatory, bristling with topical allusions and scathing raillery, it was a hustings masterpiece. But it was almost wholly critical and destructive. The affirmative and regenerative aims of Socialism hardly emerged from it. There was hardly a ray of idealism in it. Capitalism was shown to be wasteful and wicked, but Socialism was not made to appear more practicable or desirable."

In the 1885 General Election, Hyndman and Champion, without consulting their colleagues, accepted £340 from the Conservative Party to run parliamentary candidates in Hampstead and Kensington. The objective being to split the Liberal vote and therefore enable the Conservative candidate to win. This strategy did not work and the two SDF's candidates only won 59 votes between them. The story leaked out and the political reputation of both men suffered from the idea that they were willing to accept "Tory Gold". Ramsay MacDonald was one of those who resigned from the SDF over this issue, claiming that Hyndman and Champion "lacked a spirit of fairness".

In 1886 the SDF became involved in organizing demonstrations against low wages and unemployment. After one demonstration that led to a riot in London, three of the SDF leaders, H. M. Hyndman, John Burns and H. H. Champion, were arrested but at their subsequent trial they were acquitted.

Some members of the Social Democratic Federation disapproved of Hyndman's dictorial style and the way he encouraged people to use violence on demonstrations. In December 1884 William Morris and Eleanor Marx left to form a new group called the Socialist League. H. H. Champion, Tom Mann and John Burns also left the party. Although the membership was never very large, the Social Democratic Federation continued and in February 1900 the group joined with the Independent Labour Party, the Fabian Society and several trade union leaders to form the Labour Representation Committee.

The Labour Representation Committee eventually evolved into the Labour Party. Many members of the party were uncomfortable with the Marxism of the SDF and Hyndman had very little influence over the development of this political group. In August 1901 the SDF disaffiliated from the Labour Party.

H. M. Hyndman eventually established a new group, the British Socialist Party (BSP). The BSP had little impact and like the SDF, failed to win any of the parliamentary elections it contested. Hyndman upset members of the BSP by supporting Britain's involvement in the First World War. The party split in two with Hyndman forming a new National Socialist Party. The Social Democratic Federation continued as a separate organisation until 1939.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923)

William Morris joined the Democratic Federation in 1883. He favoured a distinctively Socialist policy, and his body became the Social Democratic Federation in 1884. It soon became manifest that differences of opinion existed, and no doubt some incompatibility action was a bone of contention. William Morris and other members of the executive decided to resign, and to form the Socialist League.

(2) Edward Carpenter joined the Social Democratic Federation in 1883.

My ideas had been taking a socialistic shape for many years; but they were lacking in definite outline. That outline as regards the industrial situation was given me by reading Hyndman's England For All. Later on in the same year I one evening looked in at a committee meeting of the Social Democratic Federation in Westminster Bridge Road. It was in the basement of one of one of those big buildings facing the House of Commons that I found a group of conspirators sitting. There was Hyndman, occupying the chair, and with him round the table, William Morris, John Burns, H. H. Champion, J. L. Joynes, Herbert Burrows, and others.

(3) George Lansbury, Looking Backwards and Forwards (1935)

I was a great admirer of Henry George and believed firmly in the taxation of land values. During the years 1886 to 1892 I came more and more under the influence of William Morris and H. H. Hyndman, Will Thorne, Tom Mann, Ben Tillet, and decided to join the Social Democrats.

(4) Emanuel Shinwell, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

My experience among the miners in some of the mining villages of Fife and Lanarkshire was that the policy of the Social Democratic Federation made a greater appeal than that of the I.L.P. The miner everywhere is suspicious of novelty until he has studied its advantages and disadvantages. The Social Democratic Federation was so close to the old Radical movement that the miner could accept it without misgivings despite the fact that it was essentially English, inspired by Marx's best-known English disciple, H. M. Hyndman, and with little Scottish blood in its hierarchy at the outset. England for All, the title of Hyndman's exposition of the S.D.F. policy, was hardly conducive to the creation of enthusiasm across the Border, though the nationalism we know in Scotland today was not at the time so marked. In the event, the S.D.F.'s powers soon declined, for England for All was really just an anglicized simplification of Marxian views, written without acknowledgment to the originator. Marx did not forget the slight, and by the time I began to read Marx it was the I.L.P. which had received the seal of approval from his collaborator, the other great European Socialist force, Engels.

Two notable S.D.F. members in my day, who played a leading part on the Clydeside, deserve mention; the likeable but formidable Willie Gallagher, and that great exponent of Socialism, John McLean, both of whom served several terms of imprisonment because of their political activities.

(5) Theodore Rothstein, The Social Democrat (March, 1908)

When all is said and done, however, the charge preferred by Marx and Engels against the policy of the S.D.F., as distinguished from its leaders, remains. That charge was, that its members regarded their Socialism as a dogma to be forced down the throats of the working class, and not as a movement which the proletariat has to go through with the assistance of the more conscious Socialist elements. The latter must accept the working-class movement at its starting point, go hand in hand with the masses, give the movement time to spread and consolidate, be its theoretical confusion never so great, and confine their efforts to pointing out how every reverse and every mistake was the necessary consequence of the theoretical inadequacy of the programme. As the S.D.F. did not do so, but insisted on the acceptance of the dogma as the necessary condition of their co-operation, it remained a sect and “came from nothing, through nothing, to nothing.”

Such was the charge. Was it justified? There can be no doubt that the Socialist policy as laid down by Marx and Engels in the above words was theoretically perfectly correct. It was in the Communist Manifesto that they had first proclaimed the principles of Socialist tactics by declaring that the Communists did not form a party separate from the general working-class movement, but represented in that movement its own future. One cannot help thinking, however, that when urging the same ideas thirty and forty years later upon the English Socialists they did not take sufficiently into account the difference in the conditions as between Germany of 1848 (it was primarily for German Communists that the Manifesto was composed) and England of the eighties. In Germany the proletariat was at the time mentioned only just evolving. It was largely as yet a raw material, confused but plastic, whose chief disadvantage, from the Socialist standpoint, consisted in the multitude of petty bourgeois notions under which it was still labouring. It was clearly the duty of Socialists to bring light into those masses by moving together with them much as a good pedagogist moves in the midst of his children, guarding them, when possible, against mistakes, but never lecturing them, never placing himself above them, always keeping patience with them, invariably allowing them to learn through mistakes and failures. This is the soundest line of conduct in all young capitalist countries, such as Germany was half a century ago, or America was in the early eighties, or Russia is at the present moment. It was also the policy of the Chartists in the latter thirties and early forties, when the British proletariat had just discovered for the first time its fundamental distinction from the middle classes.

Very different was the position in England in the eighties, when the Socialist movement was started by Hyndman and the S.D.F. The English working-class was no longer a raw material which one might help to shape according to one’s better light. It was well organised in trade unions, it had behind it a long and very pronounced historical experience, it had its traditions and acquired habits of mind – in short, it was a manufactured article, as it were. And what was still more important, those traditions and habits of mind were thoroughly bourgeois – not negatively-bourgeois as is the case with a working-class still unripe, but positively-bourgeois as comes from over-ripeness. In these circumstances what could and should have been the policy of the Socialists? The principles laid down in the Communist Manifesto were correct as ever – only they were in the English conditions of the eighties utterly inapplicable. By no permanent and intimate co-operation with the masses, such as was urged by Marx and Engels, could the Socialists have hoped “to revolutionise them from within”; on the contrary, what would have been achieved was merely the adaptation of the Socialists to the mental level of the masses which spelt not confusion” not theoretical unripeness, but Liberalism. Those who doubt this need only turn to the fate of those numerous ex-Socialists who have left the S.D.F. and “gone over” to the masses, but are now to be found in the ranks of the two bourgeois parties. The English working-class was not to be revolutionised from within, as many attempts, started with the blessings of Engels. himself, have proved by their dismal failure. Indeed, the International itself, in so far as Marx, in starting it, had the hope of “revolutionising” the British trade unions, was a ghastly failure – not only did the trade unions prove obstinate in their Liberalism and bourgeois Radicalism, but they ultimately withdrew, and the whole business collapsed.

No, however lamentable it may appear now, a certain intransigence, a certain modicum of impossibilism, was in those days not only inevitable but really necessary, if the Socialist movement was to subsist. It was all very well for Engels – and the idea is still entertained largely even now – to ascribe the impossibilist tendencies of the S.D.F. of that time to the baneful influence of Hyndman and other leaders; rather were Hyndman and his colleagues themselves semi-impossibilists only because the condition of their work demanded it. No other organisation, with totally different men at the top, would have conducted itself differently; if it had, it would have disappeared where the S.D.F. had survived.

(6) David Kirkwood, My Life of Revolt (1935)

For some years before the outbreak of war I had been a Socialist, but I had taken no part in any movement except the Trade Union and Temperance. There were great discussions at that time about the Social Democratic Federation, which was in turmoil. H. M. Hyndman and Harry Quelch, two of the foremost pioneers of Socialism, were being opposed by a younger school led by Yates, Matheson, and Tom Clark. When this group failed in their effort to capture the Social Democratic Federation, they formed the Socialist Labour Party. This Party had one outstanding feature. It was purely educative, setting out to pervade the people with the idea that in Socialism lay their only hope of economic progress. They used to tell the people not to vote for them unless they were in favour of Socialism. At that time there was a great deal of talk among the working class that certain individuals took an interest in the working-class movement only for the fleshpots of Egypt - that is to say, to become well-paid Trade Union officials. To prove that they were not of this type, the S.L.P. made it a condition of membership not to take a paid position in the Trade Union movement and to work for the cause and not for filthy lucre.

(7) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

I have to confess that my fidelity to the SDF was short-lived. While a willing and interested student of Marx I was fed up with the excessive adulation of the man and the attitude of the SDF leaders that he was a prophet and his book akin to the Bible as regards the distillation of truth in it. Hyndman's recurrent references to his friendship with Marx were both boring and suspect.

Hyndman had talked to Marx only once so far as anybody knew - in 1880. Twenty-six years later he was still describing the master's conversation as if it had happened yesterday. The suggestion that Marx liked and trusted Hyndman, which the latter was never tired of explaining, was probably really a confession that Hyndman had a childlike faith in, and unrequited adoration for, Marx.

Marx was not the type of man who liked anybody, least of all a rich and aristocratic young man with the manners and accent bred into him at Eton and a high regard for the genteel frock coat and top-hat without which Hyndman never appeared in public.

(8) Paul Thompson, Socialist, Liberals and Labour (1967)

The story of the foundation of the Social Democratic Federation (the S.D.F.), the first avowedly socialist political party in England, has been recounted in some detail by historians of socialism. It will be sufficient here to say that it resulted from a coincidence of radical dissatisfaction with Gladstonian Liberalism, with the arrival on the political scene of H. M. Hyndman. It is clear from reports in the Radical that already some club speakers were urging the need for "a labour party which should be independent of the Liberal party" and arguing that "nearly every internal struggle in a country - whether it be Nihilism in Russia, Socialism in Germany, Communism in France, or Radicalism in England-could be reduced to this logical fact-a fight between the profit producer and the profit receiver. In 1881 the Radical began a campaign, very probably suggested by Hyndman, for "a non-Ministerial Radical party" to be led by Joseph Cowen, the radical M.P. for Newcastle. The first of a series of conferences resulting in the formation of the new party, the Democratic Federation, was held under Cohen's chairmanship in February. But the fact that the Democratic Federation survived, and developed into a socialist party, was because it very rapidly passed to Hyndman's leadership.

A man of independent means, widely travelled, a Cambridge graduate aged nearly 40, Hyndman was temperamentally a radical imperialist Conservative in the tradition of Disraeli, who had been converted to the Marxist standpoint by reading a French translation of Capital in 1880. He was to be the undaunted propagandist of English socialism for another forty years, but in spite of his dedication he was

Ensor found Wells "absurd" and recorded repeated "tedious discussion" and "silly personal bickering". Consequently although nine of the fifteen reform candidates were elected they were unable to form a united group. As Wells wrote to Ensor afterwards, "There ain't no always an incongruously unsuitable leader. A natural gambler and adventurer who delighted in political crisis, he totally lacked the personal tact and strategic skill which a successful politician needs. The personal enemies he made included Marx and Engels, William Morris, and the trade unionist socialist pioneers John Burns and Tom Mann. He regarded first the Independent Labour Party and then the early Labour Party with scorn. He opposed the campaign for an Eight Hour Day as a diversion, and denounced the "First of May folly". He regarded trade unions as politically unimportant and their leaders as "the most stodgy-brained dull-witted and slow going time-servers in the country". He opposed both the syndicalists and the suffragists in the 1900s, and suggested that women who struggled for their emancipation as a sex question "ought to be sent to an island by themselves". He was a persistent anti-semite, became a violent anti-German, supported Carson and the Ulster Protestants and backed allied intervention against the Russian revolution.' In considering the mistakes made by the S.D.F. in London and the eventual failure of Marxist socialism to consolidate its early advances, it is important to remember that it suffered throughout the period from singularly unsuitable leadership.

At first the Federation was a negligible force, with only two branches in 1881-2. It quickly lost the support of the radical clubs when Hyndman's hostility to "capitalist radicalism" was made apparent. The real socialist revival was set off by Henry George, the American land reformer, whose English campaign tour of 1882 seemed to kindle the smouldering unease with narrow radicalism. This radical voice from the Far West of America, a land of boundless promise, where, if anywhere, it might seem that freedom and material progress were secure possessions of honest labour, announced grinding poverty, the squalor of congested city life, unemployment, and utter helplessness. George's book Progress and Poverty sold 400,000 copies. His argument pointed beyond land reform, and stimulated an intellectual interest in socialism, which he certainly never intended. The new atmosphere brought important recruits to the Democratic Federation in 1883 and 1884: William Morris, Dr. Edward Aveling a Darwinian chemist and secularist leader, Harry Quelch a packer in a city warehouse, H. H. Champion a former army officer, and John Burns, born in Battersea of Scots parents, a temperance enthusiast who had been influenced by an old French communard in his engineering workshop.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject