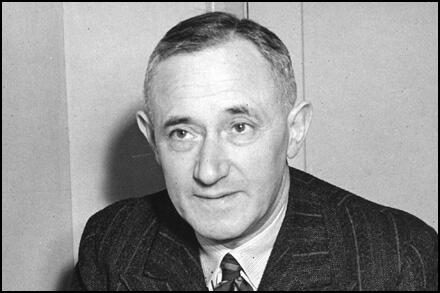

Emanuel Shinwell

Emanuel Shinwell, the son of a tailor, was born in London in 1884. One of thirteen children, Shinwell and his family moved to Glasgow and at the age of 11 began working for his father. Later he worked as a message boy and in a factory making chairs but eventually returning to the clothing trade.

In 1903 Shinwell became interested in politics. Neil Maclean gave him a pamphlet by Karl Marx entitled Wages, Labour and Capital. As his later explained in his autobiography: "I was not the first nor the last young man to discover that Marx is hard going, and his arguments on the theory of surplus value, his explanation of labour's part, and his castigation of the exploitation of the working class, were difficult for my mind to grasp. I read and re-read that pamphlet and eventually succeeded in extracting some worth-while material for discussion."

Elected to the Glasgow Trades Council in 1911, Shinwell worked closely with other socialists in Glasgow including David Kirkwood, John Wheatley, James Maxton, William Gallacher, John Muir, Tom Johnston, Jimmie Stewart, Neil Maclean, George Hardie, George Buchanan and James Welsh. .

After the war Shinwell was involved in the struggle for a 40 hour week. The police broke up an open air trade union meeting at George Square on 31st January, 1919. The leaders of the union were then arrested and charged with "instigating and inciting large crowds of persons to form part of a riotous mob". Shinwell was sentenced to five months and Willie Gallacher got three months. The other ten were found not guilty.

A member of the Labour Party, Shinwell was elected to the House of Commons in November 1922. Also successful were several other militant socialists based in Glasgow including John Wheatley, David Kirkwood, James Maxton, John Muir, Tom Johnston, Jimmie Stewart, Neil Maclean, George Hardie, George Buchanan and James Welsh.

Defeated in the 1924 General Election, Shinwell returned to Parliament in April 1928. When Ramsay MacDonald became prime minister following the 1929 General Election, he appointed Shinwell as Financial Secretary War Office. He later served as Secretary for Mines (June 1930 - August 1931).

The election of the Labour Government in 1929 coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority voted against the measures suggested by Sir George May.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government.

Shinwell, a strong opponent of MacDonald's new government, lost his seat at Linlithgow in the 1931 General Election. In 1935 Shinwell returned to the House of Commons after defeating Ramsay MacDonald at Seaham.

In 1936 Shinwell attempted to persuade the British government to supply military aid to help support the Popular Front government in Spain. Along with Aneurin Bevan, George Strauss, Sydney Silverman and Ellen Wilkinson he toured the country during the Spanish Civil War. He later wrote: "The reason for the defeat of the Spanish Government was not in the hearts and minds of the Spanish people. They had a few brief weeks of democracy with a glimpse of all that it might mean for the country they loved. The disaster came because the Great Powers of the West preferred to see in Spain a dictatorial Government of the right rather than a legally elected body chosen by the people."

After the Labour Party won the 1945 General Election the new prime minister, Clement Attlee appointed Shinwell as Minister of Fuel and Power (July 1945 - October 1947). He also served as Secretary of State for War (October 1947 - February 1950) and Minister of Defence (February 1950 - October 1951). He lost office after the Conservative Party victory in the 1951 General Election but held his seat in the House of Commons and between November 1964 and March 1967 was Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party.

Shinwell wrote three volumes of autobiography, Conflict Without Malice (1955), I've Lived Through it All (1973) and Lead With the Left (1981). Emanuel Shinwell, who was created Baron Shinwell in 1970, died aged 101, of bronchial pneumonia, on 8th May 1984.

Primary Sources

(1) Emanuel Shinwell wrote about his education in his autobiography, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

When I was eleven years old my father moved to another part of Glasgow and I had to leave the Adelphi Terrace school. My father then employed me as an errand boy in his business, and my organized education was over. Many times I have referred to this when I have addressed meetings where the audience was on a somewhat high intellectual level and the subject of a commensurate standard. I have disclaimed any intellectual pretensions, on the grounds of leaving school at so early an age. I have spoken of my melancholy reflections because of this, and how I was only consoled when years afterwards I arrived at the House of Commons and there saw some of the products of the universities and high scholastic institutions.

But how I regret those early years and the loss I sustained! It has been a long and costly struggle ever since: the lack of direction in my studies, the need for intellectual discipline, the agony of composition, the reading of many books on many erudite subjects that I failed to understand. I know all about those famous people in history who, despite the lack of education, rose to great heights in the field of politics, literature, art, and in world affairs, but it is easier to smooth out the problems of living when one is endowed with all that a good education can give.

(2) Emanuel Shinwell, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

By the time I was fourteen the Boer question was the chief source of discussion. It even banished Home Rule from the scene, and by the time war broke out, a day or two before my fifteenth birthday, I was a fervid Tory, ready and willing to go to Africa and fight Kruger with my bare hands. Considering that the war was bitterly opposed by most Liberals and all Socialists it was not surprising that my father banished me from the workroom except on business at this period.

I soon found a better source of education: the Glasgow Public Library. As soon as my father's friends had effectively put a stop to further work I would hurry off and remain there until I was turned out at ten o'clock. The daring theories of evolution by Darwin I found absorbing reading, and I expanded my knowledge by reading such works of his as The Origin of Species and Descent of Man. On the same shelves were books concerned with similar scientific subjects of the day. I read works on zoology, geology, and palaeontology, for example, and was thereby encouraged to study the specimens of stuffed animals and birds, skeletons, rocks, and fossils in the Glasgow museums. I used to spend every

Saturday afternoon testing myself on the knowledge I had gained from the verbose and serious works which were the forerunners of the popular scientific works of later years.

(3) In his autobiography, Conflict Without Malice (1955), Emanuel Shinwell described Glasgow at the beginning of the Twentieth Century.

The working-class people of Glasgow lived in the grimy and ugly tenements of the Gorbals, Townhead, and Gallowgate, and the dockside areas of Anderton and Finnieston. The luckier families had two rooms: with a recessed bed - set in a hole in the wall in the kitchen for the boys and another in the parents' room for the girls. More usually the family had one room. One of Glasgow's medical officers, Dr. J. B. Russell, who attempted the well-nigh hopeless task of arousing landlords' consciences about housing conditions in the last two decades of the century, had declared that a quarter of Glasgow's 760,000 inhabitants lived in one room. One in seven of such one-room tenants took in a lodger in order to pay the rent. Another quarter of the city's population lived in two-room tenements.

Improvements and new buildings since the middle of the nineteenth century had not kept pace with the growth of population, principally due to the heavy immigration into the city. Large numbers of Irish had been coming over for years. Competition between the shipping companies made it possible for a man to cross the Irish Sea for a few shillings.

(4) Emanuel Shinwell described the meeting that took place at George Square on 31st January 1919 in his autobiography Conflict Without Malice (1955)

At the Central Police Station some of my friends were also being charged. Willie Gallagher was there, despite the fact that he had actually been given police protection so that he could bawl out to the crowd: "March off, for God's sake." David Kirkwood had also been arrested. He was excitable but was really a peaceable soul and had, as a matter of fact, been hit on the head by a policeman almost as soon as he ran down the steps of the City Chambers, being attacked from the back as he raised his hand to quieten the crowd. That might not have meant his discharge at the subsequent trial except for the lucky fact that a press photographer took a picture of the policeman's baton raised and Kirkwood collapsing - evidence which, of course, meant his dismissal from the case when the picture was exhibited.

(5) Emanuel Shinwell, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

To dismiss MacDonald as a traitor to Labour is nonsense. His contribution in the early years was of incalculable value. His qualities as a protagonist of Socialism were of a rare standard. There has probably never been an orator with such natural magnetism combined with impeccable technique in speaking in the party's history. Before the First World War his reputation in international Labour circles brooked no comparison. Keir Hardie, idolized by the theorists in the movement, did not have the appeal to European and American Socialists that MacDonald had. There is no doubt that his international prestige equalled that of such men as Jaures and Adler. Among his people in Scotland he could exert almost mesmeric influence.

No one has ever completely explained the magnetism of MacDonald as a young man. He was the most handsome man I have ever known, and his face and bearing can best be described by the conventional term "princely." Partly this was due to the spiritual qualities which are so often found in the real Northern Scottish strain, with its admixture of Celtic and Norse blood. Some of it probably came from the paternal ancestry which gave him aristocratic characteristics and marked him as a leader of men. Lesser men might despise this suggestion of heredity; the people who loved him in those early days recognized it as an inborn quality. It also put him in Parliament. Leicester was intrigued about this Labour candidate who was the sole opponent of the Tory in 1906. If he had been an uncouth firebrand it is unlikely that he would have found much favour. The immense Liberal vote was his from the start. The Liberals and sentimentalists were utterly charmed by this handsome idealist whose musical voice wove gently round their spell-bound hearts. He won that election by emotionalism rather than intellect - as others before and since have won elections.

(6) Emanuel Shinwell, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

When the Spanish Republican Government was formed in 1936 the news was received enthusiastically by Socialists in Britain. Many of the new Government members were well known in the international Socialist movement. The emergence of a democratic regime in Spain was a bright light in a gloomy period when war had raped Abyssinia, and Germany had repudiated the Locarno Treaty. On the sudden outbreak of civil war in July, 1936, Socialist movements in all those European countries where they were allowed to exist immediately took steps to consider whether intervention should be demanded.

The Fascist attack was regarded as aggression by the majority of thinking people. Leon Blum, at the time Prime Minister of France, was greatly concerned in this matter. As political head of a nation which was bordered by Spain he had to consider the danger of some of the belligerents being forced over the border; as a Socialist he had a duty to go to the help of his comrades, members of a legally elected Government, who had been attacked by men organized and financed from outside Spanish home territory.

In Britain, although the Government was against intervention, the Labour Party had to face the strong demands from the rank-and-file for concrete action. The three executives met at Transport House to consider the next move, and I was present as a member of the Parliamentary Executive. We were largely influenced by Blum's policy. He had decided that he could not risk committing his country to intervention. Germany and Italy were supplying arms, aircraft, and men to the Spanish Fascists, and Blum considered that any action on the Franco-Spanish border on behalf of the Republican Government would bring imminent danger of retaliatory moves by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany on France's eastern flank. As a result of this French attitude Herbert Morrison's appeal in favour of intervention received little support. Although, like him, I was inclined towards action I pointed out that if France failed to intervene it would be a futile gesture to advise that Britain should do so. We had the recent farce of sanctions against Italy as a warning.

(7) Emanuel Shinwell initially argued that the British government should give support to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about his visit to Spain in his autobiography, Conflict Without Malice (1955)

While the war was at its height several of us were invited to visit Spain to see how things were going with the Republican Army. The fiery little Ellen Wilkinson met us in Paris, and was full of excitement and assurance that the Government would win. Included in the party were Jack Lawson, George Strauss, Aneurin Bevan, Sydney Silverman, and Hannen Swaffer. We went by train to the border at Perpignan, and thence by car to Barcelona where Bevan left for another part of the front.

We travelled to Madrid - a distance of three hundred miles over the sierras - by night for security reasons as the road passed through hostile or doubtful territory. It was winter-time and snowing hard. Although our car had skid chains we had many anxious moments before we arrived in the capital just after dawn. The capital was suffering badly from war wounds. The University City had been almost destroyed by shell fire during the earlier and most bitter fighting of the war.

We walked along the miles of trenches which surrounded the city. At the end of the communicating trenches came the actual defence lines, dug within a few feet of the enemy's trenches. We could hear the conversation of the Fascist troops crouching down in their trench across the narrow street. Desultory firing continued everywhere, with snipers on both sides trying to pick off the enemy as he crossed exposed areas. We had little need to obey the orders to duck when we had to traverse the same areas. At night the Fascist artillery would open up, and what with the physical effects of the food and the expectation of a shell exploding in the bedroom I did not find my nights in Madrid particularly pleasant.

It is sad and tragic to realize that most of the splendid men and women, fighting so obstinately in a hopeless battle, whom we met have since been executed, killed in action - or still linger in prison and in exile. The reason for the defeat of the Spanish Government was not in the hearts and minds of the Spanish people. They had a few brief weeks of democracy with a glimpse of all that it might mean for the country they loved. The disaster came because the Great Powers of the West preferred to see in Spain a dictatorial Government of the right rather than a legally elected body chosen by the people. The Spanish War encouraged the Nazis both politically and as a proof of the efficiency of their newly devised methods of waging war. In the blitzkrieg of Guernica and the victory by the well-armed Fascists over the helpless People's Army were sown the seeds for a still greater Nazi experiment which began when German armies swooped into Poland on 1st September, 1939.

It has been said that the Spanish Civil War was in any event an experimental battle between Communist Russia and Nazi Germany. My own careful observations suggest that the Soviet Union gave no help of any real value to the Republicans. They had observers there and were eager enough to study the Nazi methods. But they had no intention of helping a Government which, was controlled by Socialists and Liberals. If Hitler and Mussolini fought in the arena of Spain as a try-out for world war Stalin remained in the audience. The former were brutal; the latter was callous. Unfortunately the latter charge must also be laid at the feet of the capitalist countries as well.

(8) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (4th April, 1938)

An incident in the House of Commons. Mr Shinwell made himself highly objectionable, and unfortunately, Commander Bower, the (Conservative) member for the Cleveland Division of Yorks shouted 'Go back to Poland' - a foolish and provocative jibe, though no ruder than many that the Opposition indulge in every day. Shinwell, shaking with fury, got up, crossed the House, and went up to Bower and smacked him very hard across the face! The crack resounded in the Chamber - there was consternation, but the Speaker, acting from either cowardice or tact, seemed to ignore the incident and when pressed, refused to rebuke Shinwell, who made an apology, as did Bower, who had taken the blow with apparent unconcern. He is a big fellow and could have retaliated effectively. The incident passed; but everyone was shocked. Bower is a pompous ass, self-opinionated, and narrow, who walks like a. pregnant turkey. I have always disliked him, and feel justified in so doing since he once remarked in my hearing 'Everyone who even spoke to the Duke of Windsor should be banished - kicked out of the country'. But the incident does not raise Parliamentary prestige, especially now, when it is at a discount throughout the world.