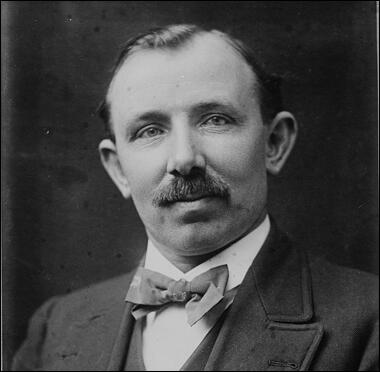

Jimmy Thomas

James Thomas was born in Newport on 3rd October, 1874. An illegitimate child, James was brought up by his widowed grandmother, Ann Thomas, who made her living by taking in washing from the officers and crews of the ships in Newport Docks.

At twelve years of age, Thomas left Angus Hill Board School and found employment as an errand boy for a local chemist shop. Three years later he became an engine cleaner on the Great Western Railway. In 1892 he passed his fireman's exams and began work at a colliery in the Sirhowy Valley.

Thomas joined the Associated Society of Railway Servants Union. He played an active role in union affairs and eventually became a full-time organiser of the union. Thomas was also involved in politics joining the newly formed Labour Party and was elected as a councillor in Swindon.

In 1909 the Derby Trades Council became unhappy with the performance of Richard Bell, the local Lib-Lab MP and in 1909 made it clear they would not support him in the next parliamentary election. Bell decided to stand down and the local Labour Party asked Jimmy Thomas to be their candidate. Thomas accepted the offer and in his election address he called for an increase in taxes on the rich and the abolition of the House of Lords. In the 1910 General Election Thomas received 10,239 votes, over 2,000 more than the nearest Conservative Party candidate.

While in the House of Commons, Thomas retained his position in the union and helped organise the strike of 1911. The following year he was an important figure in the amalgamation of several unions to form the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). In was elected General Secretary of the NUR in 1917 and two years later led the successful railway strike of 1919. When Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister after the 1924 General Election, he appointed Thomas as Secretary of State for the Colonies.

During the proposed General Strike in 1926 Thomas was asked by the Trade Union Congress to help reach an agreement with the Conservative Government and the mine-owners. According to Thomas they were close to agreement when Stanley Baldwin broke off negotiations. The reason for his action was that printers at the Daily Mail had refused to print a leading article attacking the proposed strike. The TUC negotiators apologized for the printers' behaviour, but Baldwin refused to continue with the talks and the General Strike began the next day.

When the Labour Party returned to power after the 1929 General Election, Thomas became Lord Privy Seal in MacDonald's government. This coincided with a serious economic depression and in 1931 Philip Snowden, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, suggested that the Labour government should introduce new measures including a reduction in unemployment pay. Several ministers, including George Lansbury, Arthur Henderson and Joseph Clynes, refused to accept the cuts in benefits and resigned from office.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Thomas, Philip Snowden and John Sankey agreed to join the new government.

MacDonald was determined to continue and his National Government introduced the measures that had been rejected by the previous Labour Cabinet. Labour MPs were furious with what had happened and Thomas, Ramsay MacDonald and Philip Snowden were expelled from the Labour Party.

In October, MacDonald called an election. Thomas, who stood as a National Labour candidate in Derby, won his seat in the 1931 General Election and afterwards served as Secretary for the Colonies in the government.

Thomas held his government post until May 1936, when he was accused of leaking Budget secrets to his stockbroker son, Leslie Thomas, and Alfred Cosher Bates, a wealthy businessman. In a Judicial Tribunal set up by the government, Bates admitted giving Thomas £15,000 but claimed it was an advance for a proposed autobiography. This high sum for an autobiography, not yet written, only increased suspicion of the two men's relationship, and Thomas was forced to resign from the government and House of Commons.

Thomas retired to his home, Millbury House, Ferring, where he wrote his autobiography, My Story (1937). Jimmy Thomas died on 21st January 1949.

Primary Sources

(1) Jimmy Thomas, election manifesto (1910)

We must end and not mend an assembly (House of Lords) the majority of whose only qualification is the accident of birth. You have to determine the question whether the People or the peers shall rule; whether the bread of the poor or the land of the rich shall be taxed. In short, whether the misery and degradation of thousands of our more unfortunate citizens shall continue, or a genuine effort made to alleviate their unhappy lot. Such is the issue that you will be called upon to decide, and that your verdict will be on the side of humanity against poverty is the sincere wish and belief of J. H. Thomas.

(2) Morgan Philips Price, My Three Revolutions (1969)

Early in the summer vacation (August 21st) the Labour Government resigned and each Labour M.P. received a letter from the Prime Minister informing him that he had felt constrained to form a National Government and had secured the support of Mr Baldwin, the leader of the Opposition. Some Conservative Members would be taken into the Government. Mr Snowden and Mr J. H. Thomas had agreed to continue in their offices and it was hoped that the Parliamentary Labour Party would agree with what had been done. At the same time a message arrived summoning all Labour M.P.s to attend a meeting of the Parliamentary Party in London. Incredibly, I was playing cricket when it arrived. I rushed up to

London at once. I found Members delighted that Ramsay Macdonald, Philip Snowden and J. H. Thomas had severed themselves from us by their action. We had got rid of the Right Wing without any effort on our part. No one trusted Mr Thomas and Philip Snowden was recognized to be a nineteenth-century Liberal with no longer any place amongst us. State action to remedy the economic crisis was anathema to him. As for Ramsay Macdonald, he was obviously losing his grip on affairs. He had no background of knowledge of economic and financial questions and was hopelessly at sea in a crisis like this. But many, if not most, of the Labour M.P.s thought that at an election we should win hands down. I was not so optimistic and wrote in a memorandum which I published in a local paper in my constituency at the time. "The country is thoroughly frightened and our Party has not proved that it has an alternative policy or the courage to put one through if it had one."

(3) Jimmy Thomas, resignation statement (20th May, 1936)

You will know that my only object in joining a National Government was because I felt sure that the coming together of all political parties - regardless of past differences - was the only chance of pulling this country through its crisis. Today I hold that opinion even more firmly than before, but, as far as I myself am concerned, I feel that instead of being a source of strength to your Cabinet I shall merely be a drag on it and not in position to pull my full weight. I have come to my decision because the way in which my name and private affairs have been bandied about renders my continuation as a member of the Government impossible.

(4) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (9th December, 1935)

We dined with Victor Cazalet in a private room at the House of Commons. We talked until 10.30 and then I went into the Chamber, where J. H. Thomas was ragging the Labour Opposition, and a sorry sight it was to watch them wincing under the gruelling. J. H. Thomas knows them so well, speaks their language, and is aware of their tricks and he went for them. The Socialist Opposition seem appalling; uneducated, narrow and unattractive, and the Independent Labour Party, headed by Maxton, are a quartet of loquacious jokers - a super-night at the House.

(5) David Marquand, Ramsay MacDonald (1977)

An even more distressing blow came at the end of May, when a tribunal appointed under the 1921 Tribunals of Inquiry Act concluded that J. H. Thomas had leaked certain budget secrets to the Conservative M.P. for Balham and Tooting, Sir Alfred Butt, and to an old friend and business associate, Alfred Cosher Bates. It is not at all clear that the tribunal was right. The evidence against Thomas was circumstantial, and some of it, at least, would have been disallowed in an ordinary court. If he had acted as the tribunal suggested, he had clearly committed an offence under the Official Secrets Act, but he was never charged with having done so-much less found guilty. If he had been properly tried, with the normal safeguards against hearsay evidence in operation, he might well have been found innocent. On the other hand, there could be no doubt that Butt and Bates had both behaved in a distinctly suspicious fashion - insuring themselves heavily against increases in taxation which were included in the Budget soon afterwards; doing so, for no obvious reason, wholly or partially through nominees; and on material points failing to satisfy the tribunal that they were telling the truth. There could also be no doubt that they were both close friends of Thomas, and that he had been in a position to disclose budget secrets to them had he wished to do so. More damningly still, it had emerged in the course of the hearings that Bates had paid him £15,000 as an advance on the proceeds of an autobiography which lie had not even started to write, and that in 1935 Butt had acted for him when he had insured himself for £1,000 in the event of there being a general election during the year - a transaction on which he had made a profit of more than £600. The tribunal's verdict put the seal on his disgrace, but the hearings had already disgraced him before the verdict was announced. He sent a letter to Baldwin resigning from the Cabinet a week before the verdict was known. Three weeks later, he resigned from the House of Coininons as well.

MacDonald watched all this with a kind of helpless agony. Thomas was now his oldest friend in politics - the only member of the attenuated National Labour group whose roots in the Labour movement went almost as deep as did his own; the only figure of consequence in their generation of Labour leaders who had stayed with him through all the upheavals of the last five years. At first, he convinced himself that all would be well. "Thomas' defence now in hand of solicitor," he noted loyally on May 8th. "I hope for a fine vindication ... I suspect other Cabinet quarters from whom leakages have come - wirepullers who are in constant touch with certain magnates of the press." Little by little, however, his hopes collapsed. By May 10th, he had to admit to himself that T's associates may be his undoing. I can see the public interest shifting from whether there was a leakage to what is the character of T's friends. On that the "jury of the street" may condemn him. By the 12th he was "haunted by the feeling that J.H.T. is to be condemned"; by the 19th he was convinced that Thomas "cannot now be saved". But although he reluctantly came to believe that Thomas probably had let some secrets slip, he refused to condemn him for doing so. Thomas's fault, he insisted, was merely "his well known one of being unable to hold his tongue... He will have profited nothing; he will have had no thought of anyone profiting; he just wanted to show that he carried great secrets." It was Thomas's friends who were at fault for abusing his confidence: Baldwin was to blame for holding the Budget Cabinet too long before the Budget statement. The revelation of Thomas's gamble on the date of the general election clearly came as a shock, but he was prepared to forgive even that.

(6) Jimmy Thomas, resignation speech in the House of Commons (11th June, 1936)

I do not intend to go into details: I must let those who read all the evidence and the report judge for themselves. I am, however, entitled to say to the House that I never consciously gave a Budget secret away. That I repeat, in spite of the Tribunal's findings. To attempt to deal in detail with some of my private affairs would be painful to me as it would be unfair to the House.

(7) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (11th June, 1936)

I reached the Chamber at 3 p.m. and found it expectant and nervous. At 3.30 J. H. Thomas entered, sad and aged, but sunburnt still. He sat immediately below the gangway on an aisle seat. Very soon took place one of the most poignant scenes the House has ever witnessed, when the Speaker quietly said 'Mr Thomas' and the poor man rose. He read a written statement which was simple and rather heartrending. He accepted the findings of the tribunal, but declared that he had never consciously betrayed a budget or any other secret. He was leaving the "Ouse' after twenty-seven years in its midst. He had now only his wife who still trusted him and loved him. He hoped no other member would ever be in a situation as cruel, as terrible as the one he today found himself in. Then he sat down for only a second, and there was a loud murmur of pity and suppressed admiration through the House. There was scarcely a dry eye. Mr Baldwin sat with his head in his hands, as he often does, Winston Churchill wiped away his tears. Thomas then rose again and slowly made his way out, not forgetting to turn and bow, for the last time, to the Speaker.