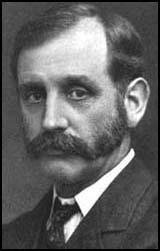

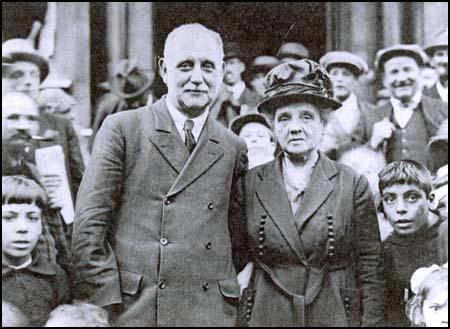

George Lansbury

George Lansbury, the son of a railway contractor, was born in Halesworth, Suffolk, in 1859. When George was nine years old the family moved to East End. George started work in an office at the age of eleven but after a year he returned to school where he stayed until he was fourteen. This was followed by a succession of jobs as a clerk, a wholesale grocer and working in a coffee bar.

Lansbury later recalled in The Miracle of Fleet Street (1925): "my own first connection with journalism took place... some time between 1874 and 1880, when, as a member of the Whitechapel Church Young Men's Association, I wrote essays for a manuscript journal produced by a group of youngsters whose ages ranged from 16 to 18 years."

Lansbury then started up his own business as a contractor working for the Great Eastern Railway. This was not a success and now married with three children, Lansbury decided in 1884 to emigrate to Australia. The Lansbury family found it difficult to settle in Australia and the following year returned to England and he began work at his father-in-law's timber merchants.

Lansbury was angry about his time in Australia and believed that he had been a victim of untrue propaganda about the country. He came to the conclusion that the emigration authorities were disseminating false information in an effort to entice immigrants to Australia. He joined the campaign against this policy and in doing so obtained his first experience of politics.

In the 1886 General Election Lansbury joined the local Liberal Party. Later that year he was elected General Secretary of the Bow & Bromley Liberal Association. However, Lansbury became disillusioned with the leadership's views on industrial issues and eventually left the party over its unwillingness to support legislation for a shorter working week.

Lansbury joined the Gasworkers & General Labourers Union and in 1889 joined a local strike committee during the London Dockers' Strike of that year. These activities brought him into contact with H.M. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation. Although the two men disagreed with each other over many issues, Lansbury decided to join the party and in 1892 established a branch of the Social Democratic Federation in Bow. This marked the start of Lansbury's long campaign against poverty and unemployment in London.

As a young man, Lansbury had been an atheist. However in the 1890s he was influenced by the religious ideas of people like Stuart Headlam and Philip Snowdon. Lansbury became a Christian Socialist and was later to play an important role in converting people such as James Keir Hardie to Christianity.In 1892 Lansbury was elected to the Board of Guardians that ran the Poplar Workhouse. Lansbury and his colleagues decided to use their power to change the system. Lansbury, unlike most Guardians, did not believe that the generous treatment of paupers would encourage more people to seek refuge in the workhouse. Over the next few years the Guardians dramatically improved the conditions in their workhouse. With the help of Joseph Fels, they also established a Laindon Farm Colony in the Essex countryside where they provided work for the unemployed and taught them the basics of market gardening.

Lansbury continued to be a member of the Social Democratic Federation and in 1895 he became the party's candidate in a parliamentary election in Walworth. He only obtained 204 votes in that election but in 1900 he obtained 2,558 against the Conservative Party candidate who won with 4,403 votes.

Lansbury found his relationship with H.M. Hyndman, increasing difficult. Lansbury disliked Hyndman's dictatorial method of running the party, he also disagreed with his Marxist views. Lansbury's socialism had been inspired by the teachings of Jesus Christ, whereas Hyndman was a devout follower of Karl Marx, an atheist. In 1903 Lansbury left the Social Democratic Federation and joined the Independent Labour Party, an organisation that contained a large number of Christian Socialists. Three years later the Independent Labour Party became the Labour Party, an organisation led by James Keir Hardie, a man who was converted to Christianity in 1897.

In 1906 the government ordered an inquiry into the running of the Poplar Workhouse. The Board of Guardians were accused of wasting the ratepayers' money by their generous treatment of paupers and the funding of the Laindon Farm Colony. Lansbury, who had been joined as a Guardian by John Burns, another leading figure in the Christian Socialist movement, argued the case for treating people in workhouses with dignity. Although the government report was critical of the Guardians, they refused to change their policy and eventually the authorities decided not to take action against them.

Lansbury was now one of the leading figures in the Labour Party and in the 1910 General Election was elected as the MP for Bow & Bromley. He later wrote: "I had previously fought many elections, but failed to secure the magic letters M.P. until reaching the age of 52. My life since a boy has been a strenuous one, always working from early morning till late at night. Earning my living took tip only a small part of my time. I can truthfully say most of my days have been spent trying to help forward the cause of the common people, to whom I am proud to belong."

Lansbury, along with James Keir Hardie, led the campaign in Parliament for votes for women. Lansbury was especially critical of the Cat and Mouse Act and was ordered to leave the House of Commons after shaking his fist in the face of Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister, and told him that he was "beneath contempt" because of his treatment of WSPU prisoners.

Hardie and Lansbury had trouble persuading all Labour MPs to support votes for women. Many of them argued that the party should make sure all working class men had the vote before it concerned itself with the franchise for women. Others argued that a policy that advocated votes for women was unpopular with the electorate and would result in the Labour Party losing seats in the next General Election.

In October, 1912, Lansbury decided to draw attention to the plight of WSPU prisoners by resigning his seat in the House of Commons and fighting a by-election in favour of votes for women. Lansbury discovered that a large number of males were still opposed to equal rights for women and he was defeated by 731 votes. The following year he was imprisoned for making speeches in favour of suffragettes who were involved in illegal activities. While in Pentonville he went on hunger strike and was eventually released under the Cat and Mouse Act.

For the next ten years Lansbury was out of the House of Commons and concentrated on journalism. In 1911 he helped start the Daily Herald and two years later became the editor of the newspaper, where he worked closely with the cartoonist Will Dyson and the writers, Henry Brailsford, William Mellor, Norman Angell, George Douglas Cole, John Scurr, Gerald Gould, Morgan Phillips Price, Henry Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp, G. K. Chesterton and Hillaire Belloc. The Countess Muriel de la Warr was the main source of funds for the newspaper. According to Lansbury she "has always been one of the first and most generous of our friends; there has never been a crisis overcome without her help."

Lansbury and his newspaper, the Daily Herald, was opposed to Britain involvement in the First World War. This made him unpopular during the nationalist fervour that developed between 1914 and 1918. In the 1918 General Election, Lansbury, like other anti-war Labour Party candidates was defeated.

In the 1922 General Election Lansbury was elected as the Labour MP for Bow & Bromley with a majority of 7,000. Lansbury was unhappy with the way the Daily Herald became more conservative in its reporting after being taken over by the Labour Party and the TUC after 1923.

Lansbury was also a member of the Poplar Council. The Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats in November 1919. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury, the new mayor of Poplar, proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie Lansbury said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council were now put in a difficult position. Harry Gosling volunteered to negotiate a settlement. As he later recalled: "The actual drafting of the document was no easy matter with such critics as George Lansbury and his son Edgar, Susan Lawrence, John Scurr, and all the others round the table, ready to object at any chance word and upset the whole thing in their eagerness to uphold their cause. Every one of these men and women stood for what was in their view a great principle, and yet a formula had to be found to enable the judges to release them."

On 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

While in Holloway Prison, Lansbury's daughter-in-law, Millie Lansbury developed pneumonia and she died on 1st January 1922. According to Janine Booth she had told friends " that imprisonment had weakened her physically, leaving her body unable to fight off the illness that killed her." Lansbury said: "Minnie, in her 32 years, crammed double that number of years' work compared with what many of us are able to accomplish. Her glory lies in the fact that with all her gifts and talents one thought dominated her whole being night and day: How shall we help the poor, the weak, the fallen, weary and heavy-laden, to help themselves? When, a soldier like Minnie passes on, it only means their presence is withdrawn, their life and work remaining an inspiration and a call to us each to close the ranks and continue our march breast forward."

In the 1923 General Election, George Lansbury, John Scurr and Susan Lawrence were all elected to the House of Commons. The Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions".

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. MacDonald had not been fully supportive of the Poplar Councillors since he thought that "public doles, Popularism, strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement." George Lansbury was therefore not offered a post in his Cabinet.

John Wheatley, the new Minister of Health, had been a supporter of the Poplar Councillors. Edgar Lansbury wrote in The New Leader that he was sure that Wheatley would "understand and sympathise with them in this horrible problem of poverty, misery and distress which faces them." Lansbury's assessment was correct and as Janine Booth, the author of Guilty and Proud of It! Poplar's Rebel Councillors and Guardians 1919-25 (2009), has pointed out: "Wheatley agreed to rescind the Poplar order. It was a massive victory for Poplar, whose guardians had lived with the threat of legal action for two years and were finally vindicated." A. J. P. Taylor has argued that at this time Lansbury was "the most beloved figure in modern British politics."

In 1925 Lansbury started the Lansbury's Labour Weekly. The newspaper rapidly reached a circulation of 172,000 and provided an important source of news during the 1926 General Strike. Although his left-wing ideas made him unpopular with some of the leaders of the Labour Party, Lansbury was elected Chairman party in 1928. The following year he became Commissioner for Works in the Labour government led by Ramsay MacDonald.

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. In January 1929, 1,433,000 people were out of work, a year later it reached 1,533,000. By March 1930, the figure was 1,731,000. In June it reached 1,946,000 and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000. That month MacDonald invited a group of economists, including John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole and Walter Layton, to discuss this problem. However, he rejected all those ideas that involved an increase in public spending.

In March 1931 Ramsay MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. The committee included two members that had been nominated from the three main political parties. At the same time, John Maynard Keynes, the chairman of the Economic Advisory Council, published his report on the causes and remedies for the depression. This included an increase in public spending and by curtailing British investment overseas.

Philip Snowden rejected these ideas and this was followed by the resignation of Charles Trevelyan, the Minister of Education. "For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative."

When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it forecast a huge budget deficit of £120 million and recommended that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. The two Labour Party nominees on the committee, Arthur Pugh and Charles Latham, refused to endorse the report.

The cabinet decided to form a committee consisting of Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham to consider the report. On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to MacDonald, describing the May Report as "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read." He argued that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the Gold Standard and devalue sterling. Two days later, Sir Ernest Harvey, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, wrote to Snowden to say that in the last four weeks the Bank had lost more than £60 million in gold and foreign exchange, in defending sterling. He added that there was almost no foreign exchange left.

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the MacDonald Committee that included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Arthur Henderson and William Graham rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made.

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Susan Lawrence both decided to resign from the government if the cuts to the unemployment benefit went ahead: Pethick-Lawrence wrote: "Susan Lawrence came to see me. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, she was concerned with the proposed cuts in unemployment relief, which she regarded as dreadful. We discussed the whole situation and agreed that, if the Cabinet decided to accept the cuts in their entirety, we would both resign from the Government."

Ramsay MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis on 23rd August. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through."

According to Harold Nicolson, the King decided to consult the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal Parties. Herbert Samuel told the King that he should try and persuade MacDonald to make the necessary economies. Stanley Baldwin agreed and said he was willing to serve under MacDonald in a National Government.

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself."

On 24th August 1931 Ramsay MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government.

The Labour Party was appalled by what they considered to be MacDonald's act of treachery. Arthur Henderson commented that MacDonald had never looked into the faces of those who had made it possible for him to be Prime Minister.

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249, but only 12 Labour M.P.s voted for the measures.

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all members of the National Government including Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly."

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Lansbury won his seat for Bow & Bromley and became the leader of the Labour opposition.

Ben Pimlott has argued in Labour and the Left (1977): "Lansbury's politics, rooted in bitter experience of unemployment and hardship as an emigrant in Australia in the 1880s, and belonging to the oldest traditions of Christian Socialism and street corner demogoguery, were in some ways suited to the beleaguered opposition of 1931. One reaction to the crisis and defeat was an eagerness to return to fundamental principles: Lansbury reflected this mood."

Lansbury hated fascism but as a pacifist he was opposed to using violence against it. When Italy invaded Abyssinia he refused to support the view that the League of Nations should use military force against Mussolini's army. After being criticised by several leading members of the Labour Party, Lansbury resigned as leader of the party.

Lansbury spent the last few years of his life trying to prevent a Second World War. He travelling throughout Europe meeting the political leaders of the various countries. After having talks with Adolf Hitler he believed it was still possible to reach an agreement that would avoid a war. His efforts ended in failure and George Lansbury died a disillusioned man on 7th May, 1940.

Primary Sources

(1) George Lansbury, Looking Backwards and Forwards (1935)

There is one outstanding lesson I have learned is that wealth can only be acquired at the expense of others. I say this with the absolute assurance that it is an indisputable statement of fact. Also, that all of us, no matter how skilled we are, or however much ability we possess, do in fact depend on our daily bread, our comforts, and material pleasures on the toil and labour of the masses who often live unrequited lives of toil and hardship.

(2) Ben Pimlott, Labour and the Left (1977)

Lansbury's politics, rooted in bitter experience of unemployment and hardship as an emigrant in Australia in the 1880s, and belonging to the oldest traditions of Christian Socialism and street corner demogoguery, were in some ways suited to the beleaguered opposition of 1931. One reaction to the crisis and defeat was an eagerness to return to fundamental principles: Lansbury reflected this mood.

With such a massive imbalance between the two sides in Parliament, there was a real danger that the opposition powers of scrutiny would fall into disuse; Lansbury had to see that Government Bills and Votes of Credit were subjected to as vigorous a criticism as in a normal Parliament. He also had to keep up the morale of outnumbered and outgunned backbenchers, organise the very small number of articulate Labour MPs to speak on every conceivable topic, and provide an inspirational lead for the demoralised rank-and-file outside. It was a measure of his success that when he found his position untenable in 1935 because of his pacifist objection to Labour's support for sanctions in the Italy-Abyssinia dispute, a large majority of the PLP asked him to reconsider his resignation.

Lansbury's reputation as a left-winger was based on his pacifism, his support for minority causes and his refusal to compromise on matters of principle, not on any inclinations towards marxism. He had little sympathy for the rebellious ILP. When Maxton gave trouble, Lansbury was as firm as Henderson that ILP members must subscribe to Labour Party Standing Orders or get out. On domestic policy he was essentially orthodox, believing that Labour and the Nation and the 1931 Election Manifesto contained "the real guts of the position". Before foreign policy became a major issue his only serious disagreement with official policy was one in which the Party was to the left of him: Lansbury favoured a personal means test (as opposed to the Government policy of a household means test), while the official Party view was against the means test altogether.

Yet Lansbury's emotionalism and lack of incisiveness infuriated trade unionists like Bevin and Citrine, while an irreverence of authority, and a stubborn resistance to influence when his convictions were challenged, irritated "respectable" leaders outside Parliament and helped to create a gulf between the PLP and Transport House; from 1934 relations deteriorated badly over his refusal to countenance the possibility of armed resistance to the Dictators.

(3) George Lansbury, The Miracle of Fleet Street (1925)

I was returned to Parliament as Member for Bow and Bromley. I had previously fought many elections, but failed to secure the magic letters M.P. until reaching the age of 52. My life since a boy has been a strenuous one, always working from early morning till late at night. Earning my living took tip only a small part of my time. I can truthfully say most of my days have been spent trying to help forward the cause of the common people, to whom I am proud to belong. At this moment, when asked to assist in founding a daily Labour paper, I was a Member of Parliament, a Poor Law Guardian, Borough Councillor, and member of the London County Council. In addition, I was in business, earning my living by the sweat of my brain.

In my spare moments I wrote articles, served on Labour committees, and spent nearly every weekend addressing two or three Labour meetings in towns and villages from John o' Groats to Land's End.

(4) George Lansbury, The Miracle of Fleet Street (1925)

Muriel Countess de la Warr also sent a subslantial sum (to the Daily Herald), and has always been one of the first and most generous of our friends; there has never been a crisis overcome without her help. She is one of the few titled women in our land who for years past has sleadily supported our Movement; and not only the Labour cause, but other unpopular rnovements - the Irish and Indian demand for Home Rule, Women's Suffurage, and the great cause of Pacifism. Her son, Earl de la Warr, was a member of the first Labour Government. If he serves the Cause as wholeheartedly as his mother has served all good causes, Labour in him will have secured one of its finest recruits.

(5) George Lansbury, The Miracle of Fleet Street (1925)

I am a Communist, one who believes that the ultimate goal which the Labour Movement exists to reach is the social ownership of all the means of life to be organised for the use and service of all; my differences with the Communist Party are purely concerning organisation and method.

(6) George Lansbury, The Miracle of Fleet Street (1925)

I never agreed entirely with Dyson's method of expression. Theirs was mainly the good old gospel of hate. I can hate conditions with the best or the worst of men, but I never have felt hatred of anybody. It is possible to dislike people's ways, but who am I to think I am worthy to judge them? Dyson's cartoons were masterpieces of cynicism and sardonic humour. Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, J. H. Thomas, the Webbs, Shaw and all the fabian family were stripped bare, shorn of all their glory, and treated like ordinary, stupid, or, on occasion, rather cunning people.

(7) George Lansbury, Looking Backwards and Forwards (1935)

Campbell-Bannerman was kindness itself. I often wonder what the developments in English politics would have been had this genial, kindly Scotsman lived. There might have been no war in 1914; the course of the Labour Movement might have been different - for this man believed in peace and was not afraid of the word Socialism, and did believe unemployment was a national problem and the unemployed the care of the State.

(8) George Lansbury, Looking Backwards and Forwards (1935)

The Jew, whether British or foreign, wherever he was born and whatever his colour or creed, was for me even when I was a boy "one of God's children". There are certain distinctions between all of us, and there are distinctions between races too, though these latter seem less marked when we investigate closely.

Jews do seem to have a facility for the quick acquisition of wealth which the Gentiles would be only too glad to imitate. When times are bad they never seem to suffer quite so badly as others; they stand together and by one another. They care for their parents, and their children are really loved. In the poorest parts mothers carry their little ones to school wrapped up from the rain.

When trade unionism among the casual labourers and unskilled workers was at a very low ebb - indeed, it was almost non-existent - it was Jewish agitators who, by persistent propaganda, helped to bring them into the British trade unions.

Some Jews are good Tories, others are Liberals, Communists and Socialists, Trade Unionists and Co-operators. In the main, the best description of them is that they are good citizens. I have known thousands of them of all ages intimately and have received great kindness from many of them. As I consider the change in East London's population I am convinced that it is nonsense to pretend we have been injured by the huge Jewish immigration. I think we have become better.

(9) George Lansbury, Looking Backwards and Forwards (1935)

I was a great admirer of Henry George and believed firmly in the taxation of land values. During the years 1886 to 1892 I came more and more under the influence of William Morris and H. H. Hyndman, Will Thorne, Tom Mann, Ben Tillet, and decided to join the Social Democrats.

(10) George Lansbury, Looking Backwards and Forwards (1935)

I have heard some remarkable women orators. Some of them stand head and shoulders above all others. There was Catherine Booth, mother of the Salvation Army, who was one of the simplest exponents of the gospel of love I have ever heard. I think her speeches, sermons and appeals on behalf of the weak and the fallen were among the finest pieces of simple arresting oratory I have ever heard.

Her theology was rather hard and narrow, and very dogmatic. Later on she threw her energy into work on behalf of young girls and illegitimate babies. Her whole soul and spirit was poured out in an unceasing effort to make men realize their responsibility. In politics, she demanded legislation to raise the age of consent and provision for the maintenance of these unfortunate victims of our lack of individual and social responsibility.

(11) George Lansbury, Looking Backwards and Forwards (1935)

Another very gentle and lovable woman was Mrs. Josephine Butler. Once, in the big St. Mary's schoolroom in Whitechapel, I listened to her with tears running down my cheeks as she told of the cruel and barbarous workings of the Contagious Diseases Acts. Mrs. Butler left a comfortable rectory to fight this fight on behalf of womanhood. She had to face tremendous opposition, gross distortion and misrepresentation. There was at the beginning no organisation, either of women or men, to stand with her. Nor did her own sex support her. But the unremitting toil of this fine Christian woman, not overblessed with physical strength, and not an orator in the accepted sense, at last won her victory, and the "C.D." Acts were repealed.

(12) Margaret Cole worked closely with George Lansbury during the First World War.

George Lansbury was not yet the Mayor of Poplar and leader of the movement to make the rich districts of London contribute to the upkeep of the poor ones, not yet chief of the Labour Party or even in Parliament, was nevertheless set to become father-confessor and Santa Claus to all the most "ornery" spirits of the Left; he was a strong pacifist on Christian grounds, and was occasionally worried by the eagerness with which his Socialist contributors greeted mild outbreaks of violence in industrial disputes. (His daughter Daisy married my brother Ray.)

(13) Henry Hamilton Fyfe became editor of the Daily Herald in 1922.

The Daily Herald had never emerged entirely from the first stage of its existence as a daily strike sheet a year or two before the war. While the war was on, it became a weekly with a bite to it. In 1919 it resumed appearance as a daily with so much of the old bite left that it gained ground slowly. Most supporters of Labour have Tory tastes. They dislike actual changes, however loudly they may demand future reforms. They were used to a certain type of daily newspaper; the Herald did not conform to type. Also it attacked most of the leaders whom Labour people had been taught to revere. Those leaders hated Lansbury, the founder of the paper, who had, with immense energy, collected funds for its rebirth. They did more to hinder than to help it on.

(14) Harry Gosling, Up and Down Stream (1927)

What an extraordinary drama it was, with its secret messages, its nocturnal meetings in prison board rooms, its almost miraculous yielding of prison bars! It would have made a splendid Bolshevik play, only it was so essentially British that no other country but our own could possibly have produced it. But it is all very well to jest: the Poplar problem has not been solved nor ever will be by any melodrama, however daringly conceived and played. The bitterness, the want and suffering which is at the root of it all will remain with us until men and women have learned what Socialism has to teach. Feeling and fighting does its bit, but collective thinking and the intelligent application of thought to social life are better and stronger weapons by far.

Let me tell the story of Poplar as I remember it, for quite contrary to my inclination I had a remarkable part to play in the drama.

The slump after the war found many of the East End boroughs in a pretty bad plight. The high cost of living and the increasing amount of unemployment were reflected in the rates, which rose to hitherto unheard-of heights. In Poplar particularly the position had become unbearable, and the Borough Council found themselves faced with precepts from the London County Council, the Metropolitan Police, and the Metropolitan Asylums Board due for payment before September 30, 1921, amounting to no less a sum than £195,52 18s. The local rate was already equal to 18s. 1d. in the pound exclusive of the precepts mentioned, which would amount to another 9s. 2d. in the pound, or 27s. 3d. in all. This was in striking contrast to the wealthier parts of London. In Hampstead, for instance, the total rate was 12s. 9d. in the pound, while in Westminster it was 11s. 1d.

For many years an agitation had been going on for an equalization of rates over the whole county of London which, if adopted, would have meant a rate of 16s. 6d. for Poplar in this particular year. Nothing of any substance had been done in this direction, however, and the borough councillors felt the time had come when something drastic must happen in order to focus attention "on the glaring injustice of the existing system." So they decided to refuse to levy rates for the central authorities, and only the rates for local purposes were collected.

This action caused the greatest consternation everywhere ; a number of conferences took place between the Minister of Health (Sir Alfred Mond) and the bodies I have mentioned; and finally the London County Council decided to apply for a mandamus compelling the Poplar Borough Council to function. Legal formalities were proceeded with and summonses were issued against the revolting councillors, who responded by marching in state to the Law Courts with the Deputy Mayor (Charles Key) and the mace at their head, to show cause, etc., in truly legal style. An order was made upon them as well, and their appeal went against them too. They then refused to obey the order, and the County Council, having once put its hand to the business, had to go on, and the rebels were committed to jail for contempt of court.The twenty-five men, including the Mayor (Sam March, L.C.C.), were sent to Brixton Prison, and the five women-Miss Susan Lawrence, L.C.C., Mrs. Minnie Lansbury, Mrs. Julia Scurr, and Mrs. Cressall - were sent to Holloway.

The Minister of Health and the London County Council were thus temporarily triumphant: the majesty of the law had prevailed and the Poplar Borough Council was its prisoner!

It is obvious that no members of a public authority can act individually - they must act collectively - and the whole object of the Poplar Council certainly was to secure collective action. But in prisons collective action is unknown. Such care is taken to preserve the individuality of prisoners that they are actually kept in separate rooms.So we now had the position that nobody could speak for the Borough Council, and yet it was unable to speak for itself. It was bad enough that the councillors were in separate cells, but when the cells were in two separate prisons on opposite sides of London what was to be done? This kind of thing might have gone on for ever!

As a matter of fact it became evident soon enough that although it had been a tedious business and had taken a long time to put them safely under lock and key, this was a comparatively simple task compared with getting them out again. And, after all, it would have to happen some time or other.

The Minister of Health was no doubt by this time being asked questions in Parliament as to what he proposed to do, and no doubt he in turn reminded the chairman of the London County Council that his precious body had brought all this about and asked him what he proposed to do? Apparently the suggestion of the chairman was that Sir Alfred Mond should send for me!

He did so and, obviously in dire despair, told me all his difficulties, how these troublesome borough councillors had got put into jail, and now nobody seemed to know how to get them out, and could I possibly do anything? I said I would do what I could, and volunteered to go and see the rebels.

But there were the prison gates, and there were the locked cells, and a hundred difficulties besides, which for the moment seemed to make any progress in the matter impossible. I went to Brixton and asked to see the Mayor of Poplar, and intimated to the Governor that I wanted to see the twenty-four other councillors as well. But he pointed out that that would take practically the whole day. I told him that as I had promised to do something I would not let time stand in my way ; would it not be possible for me to see them all at once? By way of reply he read to me so many regulations that I began to wonder if I should ever see any of them at all!

(15) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954)

Lansbury was by nature an evangelist rather than a Parliamentary tactician. Yet during those years in which he led the small Party in the House he showed great skill and powers of everyday leadership. A leading Conservative once replied to a Labour Member who said that he thought George Lansbury was one of the best men he had ever known - The best! Is that all? He's the ablest Opposition Leader that I have ever known." It was, of course, a great source of strength to him that he commanded the personal affection of his followers. He had also a wise tolerance - an attribute which is not so common in the enthusiast.

(16) Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

The Labour opposition was led by George Lansbury who, as a sincere and devout churchman, did not hesitate to invoke Christian principles in his search for a solution to the problem of poverty. This led to the Tory riposte that "there is nothing in the Bible about a seven-and-a-half hour day." To the rising growth of left wing feeling, the Government replied in a way that failed to satisfy those who were worst hit - notably the unemployed who were soon to number three million. The problems arising from the international economic crisis touched every consumer in the country - some very cruelly. The middle and upper classes became troubled by the social unrest amongst the working-class unemployed, and many were finding it harder and harder to see the working-class reaction as altogether blameworthy. I was becoming aware that the world was subject to forces that hitherto had not been brought to my attention but which I could no longer ignore. I did in fact have one last try at doing so during the coming university long-vacation.

(17) William Patterson, The Man Who Cried Genocide (1971)

In my quest for a room, I had become acquainted with the London Daily Herald, organ of the British Labour Party. I was attracted by its editorial policy and its approach to events, including comments on the war just concluded and the Civil War in Russia. I decided I would like to talk to Robert Lansbury, whose byline was prominent in the paper. He was its editor and publisher, as well as being one of the leading figures of the British Labour Party. I went boldly to the paper, asked for Mr. Lansbury and had no trouble getting into his offices. The dingy offices on Fleet Street were in what Americans would call a loft building. I found Mr. Lansbury in a sort of cubbyhole, behind a desk piled high with papers and surrounded by newsmen. He quickly dismissed everybody and we started to talk.

He was anxious to find out about conditions in the United States, especially those faced by the Negro. Finally he invited me to do an article on the Negro's problems for the Herald. When I told him of the limitations of my experience, he still insisted. So I wrote an article, which was published while I was still in London, describing the development of the struggles of the Negro in the United States as I saw them. I drew heavily on my reading of the Messenger and the Crisis.

In our talks, Lansbury probed into my reasons for wanting to go to Africa. When I explained, he said, "Well, you're running away from struggle. You tell me that you want to fight for human rights and dignity, yet you are trying to get away from the main fight. Why don't you return to the States? Your country is going to be a great center of struggle for human rights and liberty. What will the position of the Negro be as the struggle develops?" I had no answer to his questions.