G. K. Chesterton

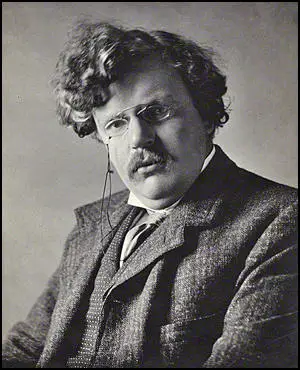

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, the elder son of Edward Chesterton and his wife, Marie Louise Grosjean, was born on 29th May 1874 at 32 Sheffield Terrace, Campden Hill, London. His father was an estate agent.

According to his biographer, Bernard Bergonzi, when his younger brother, Cecil Chesterton, was born, he "greeted his arrival with the satisfied response that now he would have someone to argue with, and the brothers went on cheerfully arguing throughout their lives, though Cecil had the more sharply polemical temperament."

Chesterton later recalled in his autobiography that he was a slow developer, not speaking until he was nearly three, and not reading until he was eight. There were plenty of books in the house and he became a passionate reader. He admitted that he had a sheltered and happy childhood in a comfortable middle-class home, where his interests in art and literature were encouraged by his parents. Chesterton was sent to St. Paul's School. Although he was an intelligent child he found it difficult to concentrate on subjects that did not interest him. He became a member of the debating society and it was the start of a life-long interest in politics. After leaving school he attended Slade Art School. At the time he thought of making a career in art, but soon found that his real gifts and inclination were for writing.

In 1895 he left art school and found work as a publisher's reader. Eventually he found work as a journalist. Like his father he was a supporter of the Liberal Party and began writing a regular column for the The Daily News. He also had articles published in Illustrated London News and The Bookman. Chesterton's first two books were collections of poetry, The Wild Knight (1900) and Greybeards at Play (1900).

Chesterton was commissioned to write a study of the poet Robert Browning. The book was published in 1903. Bernard Bergonzi has pointed out: "That he was invited to write it while still only in his twenties was a sign of his growing celebrity. The book was well received by ordinary readers but not by Browning experts, who objected to its biographical inaccuracies and frequent misquotations. Chesterton was habitually careless about questions of fact, but Robert Browning contains acute discussions of Browning's poetry; among many other things, Chesterton was an excellent literary critic. Nevertheless, the book's real interest is the extent to which he identifies with his subject, and the clues it offers to his later development. When he wrote it he was more than a young man embarking on a successful literary career. He was also engaged in a personal struggle to make sense of the world, a struggle which marked all his writing."

His brother, Cecil Chesterton, had been a socialist and a member of the Fabian Society.Meanwhile, G. K. Chesterton and his great friend, Hilaire Belloc, became supporters of Distributism, a theory based upon the principles of Catholic social teaching, especially the teachings of Pope Leo XIII and was seen as a philosophy that was opposed to both socialism and capitalism. It has been claimed that it expressed similar ideas to the anarchism of Prince Peter Kropotkin.

Gilbert Chesterton later attempted to explain the changes in his brother's political beliefs: "Thus he came to suspect that Socialism was merely social reform, and that social reform was merely slavery. But the point still is that though his attitude to it was now one of revolt, it was anything but a mere revulsion of feeling. He did, indeed, fall back on fundamental things, on a fury at the oppression of the poor, on a pity for slaves, and especially for contented slaves. But it is the mark of his type of mind that he did not abandon Socialism without a rational case against it.... The theory he substituted for Socialism is that which may for convenience be called Distributivism; the theory that private property is proper to every private citizen. This is no place for its exposition; but it will be evident that such a conversion brings the convert into touch with much older traditions of human freedom, as expressed in the family or the guild. And it was about the same time that, having for some time held an Anglo-Catholic position, he joined the Roman Catholic Church."

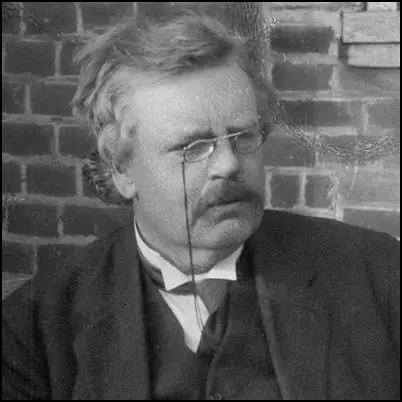

In 1911 the two brothers and Hilaire Belloc launched the political weekly, the Eye-Witness. With contributors such as George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Arthur Ransome and Maurice Baring, the journal sold over 100,000 copies a week. It also concentrated on exposing examples of political corruption, including the sale of peerages. Chesterton also published the popular novel, The Innocence of Father Brown (1911). Bernard Bergonzi points out: "Here he introduces one of the most famous of literary detectives, the insignificant-seeming little Roman Catholic priest, Father Brown, who is possessed of formidable powers of observation and ratiocination, and whose work as a confessor has given him a deep insight into human nature and the criminal mentality in particular."

In 1912 Cecil Chesterton, backed by money from his father, took over the paper. The name was changed to the New Witness and Ada Jones became assistant editor. It now concentrated on exposing examples of political corruption, including the sale of peerages. The journal also accused David Lloyd George, Herbert Samuel and Rufus Isaacs of corruption. It was suggested that the men had profited by buying shares based on knowledge of a government contract granted to the Marconi Company to build a chain of wireless stations.

In January 1913 a parliamentary inquiry was held into the claims made by New Witness. It was discovered that Isaacs had purchased 10,000 £2 shares in Marconi and immediately resold 1,000 of these to Lloyd George. Although the parliamentary inquiry revealed that Lloyd George, Samuel and Isaacs had profited directly from the policies of the government, it was decided the men had not been guilty of corruption. Godfrey Isaacs, the financier who headed the company, sued Chesterton and after being found guilty was fined £100.

On the outbreak of the First World War Chesterton became fiercely patriotic. He was willingly recruited by Charles Masterman, the head of Britain's War Propaganda Bureau (WPB), to help shape public opinion. His work included the writing of two pamphlets, The Barbarism in Berlin (1915) and The Crimes of England (1915) and numerous articles in Britain's newspapers.

Cecil Chesterton joined the East Surrey Regiment. While on leave in 1917 Ada Jones eventually agreed to marry Chesterton. Her biographer, Mark Knight, pointed out: "After rejecting his marriage proposals for many years she eventually agreed to marry him when he was enlisted as a private during the First World War. They married on 9 June 1917 at two ceremonies, the first at a register office in London and the second at Corpus Christi Church in Maiden Lane, London."

Cecil survived the war only to be taken seriously ill with nephritis shortly after the armistice and died on 6th December, 1918. G. K. Chesterton commented: "My brother, died in a French military hospital of the effects of exposure in the last fierce fighting that broke the Prussian power over Christendom; fighting for which he had volunteered after being invalided home. Any notes I can jot down about him must necessarily seem jerky and incongruous; for in such a relation memory is a medley of generalisation and detail, not to be uttered in words."

After the death of his brother he vowed to continue the pubication of the New Witness. In 1925 it was renamed GK's Weekly. Some of his friends "claimed that it made heavy demands on him for both money, to keep it afloat, and time, since he wrote much of its content himself". In 1922 Chesterton became a Roman Catholic. This influenced the subject matter of his work and he published biographies of St. Francis of Assisi and St Thomas Aquinas.

G. K. Chesterton's Collected Poems appeared in 1933 and his Autobiography, just after his death in 1936.