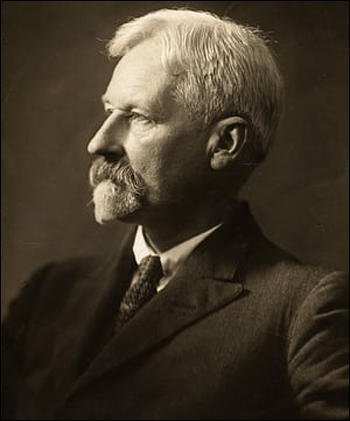

Henry Nevinson

Henry Nevinson, the son of George Nevinson, a solicitor, was born in Leicester on 11th October 1856. He attended Shrewsbury School and Christ Church College, where he came under the influence of the Christian Socialists and the ideas of John Ruskin. After university Nevinson taught briefly at Westminster School.

Nevinson travelled to Germany and on his return published his first book, A Sketch of Herder and his Times (1884). On his return to London he lived in Whitechapel and worked at Toynbee Hall.

On 18 April 1884 Nevinson married Margaret Wynne Jones, with whom he had had one daughter, Mary Nevinson, a talented musician, and one son, the successful painter Christopher Nevinson. He gradually became more radical and in 1889 joined the Social Democratic Federation. However, he disliked the authoritarianism of H. M. Hyndman and was more attracted to the anarchism of Peter Kropotkin and Edward Carpenter. Like his wife, he was very interested in the subject of social reform and spent time living among the working classes and this resulted in his next book, Neighbours of Ours.

Margaret Nevinson did charity work and and helped with St Jude's Girls' Club. In 1887 the Nevinson's moved to Hampstead (4 Downside Crescent). According to her biographer, Angela V. John she was "always a pioneer, from her shingled hair and hatred of lace curtains to her espousal of modern art, European outlook, and commitment to social justice."

In February 1892, met Nannie Dryhurst, a beautiful Irishwoman who was married to a man who worked for the British Museum. They soon became lovers and according to his biographer: "Nannie became the overriding passion of Henry's life. His interest in Irish nationalism, along with the ider concern about the self-determination of small nations, was fuelled by her."

Nevinson was employed by The Daily Chronicle and in 1897 he was sent to cover the Greco-Turkish War. His friend, Henry Brailsford, pointed out: "As a war correspondent Nevinson was always scrupulously careful in gathering his facts, and his writing often inspired those struggling towards freedom." Over the next few years he developed a reputation as an outstanding war reporter."

On 9th September 1899, Nevinson was sent to South Africa to cover the Boer War. Other journalists covering the conflict included Winston Churchill, Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, Sarah Wilson and Edgar Wallace. Nevinson was opposed to the war and he wrote in his diary that Britain's "real objects were to paint the country red on the map and to exploit the gold-mines."

Nevinson reached the garrison town of Ladysmith on 5th October. Later that month he witnessed "Black Monday" when over 800 men were taken prisoner were taken after an engagement extending about fifteen miles from Nicholson's Nek. As the Boers launched no immediate assault, the British force reorganised and constructed defensive lines around the town. The Siege of Ladysmith lasted until 28th February 1900. Nevinson's account of the siege first appeared in The Daily Chronicle. Later that year Methuen published his Ladysmith: The Diary of a Siege.

On 30th December 1901, Nevinson met Evelyn Sharp for the first time at the Prince's Ice Rink in Knightsbridge. She later recalled, "when he took my hand in his and we skated off together as if all our life before had been a preparation for that moment." They soon became lovers. Nevinson wrote in his diary that Evelyn "was both pretty and wise - exquisite in every way". Evelyn later told him: "The first time I saw you I knew you wanted something you have never got." Sharp and Nevinson shared the same political beliefs. He told his old friend from university, Philip Webb, that Evelyn possessed "a peculiar humour, unexpected, stringent, keen without poison" but "above all she is a supreme rebel against injustice.

In 1904 Nevinson visited Angola in Africa. A fellow journalist, Henry Brailsford, has argued: "The most difficult, however, of all his crusades was that which he conducted against what he saw as the virtual slavery of bonded labourers in Portuguese Angola. After a journey into the interior in 1904–5 he returned to the malaria-infested plantations of São Tomé and Principe, encountering skeletons of perished slaves along the way. His writings aimed to make clear to the consciences of his fellow Englishmen the human price of their taste for cocoa." Part of his campaign was the publication of the book, A Modern Slavery.

In 1905 Nevinson and Evelyn Sharp established the Saturday Walking Club. Other members included William Haselden, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, Clarence Rook and Charles Lewis Hind. According to Angela V. John, the author of Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009): "Although Evelyn and Henry were serious walkers, both the Saturday Walking Club and dining with friends afforded the opportunity to be together in public in a manner that was acceptable."

On 22nd January, 1905, Father Georgi Gapon, the founder of the Assembly of Russian Workers, led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in St Petersburg in order to present a petition, outlining the workers' sufferings and demands. This included calling for a reduction in the working day to eight hours, an increase in wages and an improvement in working conditions. Gapon also called for the establishment of universal suffrage and an end to the Russo-Japanese War. When the procession of workers reached the Winter Palace it was attacked by the police and the Cossacks. Over 100 workers were killed and some 300 wounded. The incident, known as Bloody Sunday, signalled the start of the 1905 Revolution.

In June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The Potemkin Mutiny spread to other units in the army and navy. Industrial workers all over Russia went on strike and in October, 1905, the railwaymen went on strike which paralyzed the whole Russian railway network. Later that month, Leon Trotsky and other Mensheviks established the St. Petersburg Soviet. Over the next few weeks over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia.

The The Daily Chronicle sent Nevinson to Russia to cover the 1905 Revolution. He arrived in late October and his first report was dated the 4th December. Nevinson was critical of Gapon's opportunism yet recognized that here was "the man who struck the first blow at the heart of tyranny and made the old monster sprawl."

Nevinson attended the Central Strike Committee and interviewed the veteran revolutionary, Vera Zasulich. He later recalled "both of us spoke abominable French at each other". He also met the leaders of the Bolsheviks, Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. He also visited Leo Tolstoy at his home in Tula.

In Moscow Nevinson saw terrible atrocities: "Officers began murdering in the name of the Tsar. Barricades were piled across the streets in the name of the people. The air crashed and whined with bullets and shells, and the snow was reddened with the blood of men and women." On his return to England he published The Dawn in Russia.

Nevinson was a supporter of women's suffrage. His wife, Margaret Nevinson, and his lover, ES, were both members of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). However, in 1906, frustrated by the NUWSS lack of success, they both joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), an organisation established by Emmeline Pankhurst and her three daughters, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.”

Henry Nevinson attended his first WSPU meeting with Evelyn Sharp on 12th February 1907. The following day they took part in a demonstration. He recorded that after being attacked by a police officer he resorted to language that was "something horrible." Later that year he joined Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Charles Mansell-Moullin, and 32 other men in forming the Men's League For Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men." Olive Banks commented: "He obviously admired the courage and determination of the militant leaders. At heart a romantic, his view of women was not without its protective side, and female beauty had a strong appeal to him. On the other hand, his passion for freedom, which inspired so much of his work, gave him sympathy also for women's need for political rights and self-determination."

At a by-election in Wimbledon in 1907 Bertrand Russell, stood as the Suffragist candidate. Evelyn Sharp later argued: "It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Lansbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war."

Another journalist, Philip Gibbs pointed out: "Henry W. Nevinson, always the defender of liberty, always a man of fearless courage, allied himself with the women's cause and marched with them when they advanced to the House of Commons, or spoke for them when they held meetings at Caxton Hall. I was at the Albert Hall where the Suffragettes kept up constant interruptions of a big meeting where Cabinet Ministers were present. Nevinson's blood boiled when he saw one of the stewards clench his fist and give a knock-out blow on the chin to one of the militant women. Other women were being roughly handled. Nevinson jumped from the stage box, and fought half a dozen stewards at once until they over-powered him and flung him out."

At first he had been a great supporter of Christabel Pankhurst, but became disillusioned, especially after her break with Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. After he failed to bring about a reconciliation between the Women Social & Political Union and Women's Freedom League he described her as "pitiless". He remained a supporter of Sylvia Pankhurst and later became an active member of the United Suffragists.

In 1909 Nevinson and his close friend, Henry Brailsford, both resigned from The Daily News when the editor refused to condemn forcible feeding. Nevinson had a reputation for writing "good and clear prose" so he had no difficulty finding other newspapers and magazines to publish his work. Two of his best-known books of this period were Essays in Freedom (1909) and Essays in Rebellion (1913).

Nevinson was spending more and more time away from the family home. He later recalled that he endured a "dismal marriage". He argued that they were incompatible as she was "by nature and tradition, catholic and conservative, always inclined to contradict me on every point and all occasions." He admitted that he "thrived on intimate friendships" but she liked "few men and fewer women". He noted that his wedding anniversary reminded him only of a "day to be blotted out."

Henry Nevinson was one of the many men who fell in love with Jane Brailsford. He later recalled that when he first saw her she was wearing a "blue, silky thinnish dress, smocked at neck and waist, pale, thin... I never saw anything so flower-like, so plaintively beautiful and yet so full of spirit and power." He made regular visits to her home where "she was most sweet, with dove's eyes, but full of dangers" but found she sometimes expressed "a mocking spirit". Jane sent Nevinson a note about her "struggle to resist my own desire" but clearly informed him that she was in charge of the situation: "I am not an iceberg. I am a wild animal but with a brain - and because of that I see how degrading it was for both of us... a mere body I will not be to anyone. You might surely find in me something more than a physical excitement. Have once before been regarded like that by a man and I took it as a proof of his inferiority."

Olive Banks argued: "Henry Nevinson had no talent for domesticity and his temperament craved a life of adventure." Women found him very attractive. Henry Brailsford has argued that "Nevinson was a handsome man, who carried himself with a noble air which earned him the nickname of the Grand Duke. His blend of humanity, compassion, and daring made him a popular figure in his own lifetime."

Nevinson continued his relationship with Evelyn Sharp. She wrote him passionate love letters. On one occasion she said: "Oh I am so glad I love some one who could never make me feel ashamed of what I have given so freely." His biographer, Angela V. John, has argued that: "He was cultured and courteous yet rebellious. He travelled to faraway and dangerous places. A touch of shyness, an ability to listen to others and an appreciation of women's rights and of intelligent women ensured that many found him irresistible." Evelyn Sharp also made a big impression on Nevinson. In 1913 he wrote to Sidney Webb: "She (Sharp) has one of the most beautiful minds I know - always going full gallop, as you see from her eyes, but very often in regions beyond the moon, when it takes a few seconds to return. At times she is the very best speaker among the suffragettes."

In September 1912 Nevinson had an argument about women's suffrage with Nannie Dryhurst and this brought an end to their affair. Nevinson wrote in his diary that his relationship with Dryhurst was "the event of my life". Although he was still having an affair with Evelyn Sharp, he wrote he was "too unhappy to think or live".

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. Nevinson was appalled by the behaviour of the WSPU and instead agreed with the Women's Freedom League approach to the conflict.

On the outbreak of the First World War he was rejected by the government as one of the six official war correspondents and was initially not allowed to enter the war zone. He wrote in The Nation on 12th September, 1914: "I have served as a correspondent for nearly twenty years in many countries and under all sorts of conditions. I think I know all the tricks of the trade, and I have seen many of them practised. But I cannot foresee how any correspondent could give away his country or do the smallest public injury under these regulations, even if he wanted to... We have all engaged servants, bought horses, and weighed our kit. Everything is ready, and yet we are kept chafing here, week after week, while a war for the destiny of the world is being fought within a day's journey, and others of our colleagues are allowed to go dashing about France in motors almost up to the very front. I do not make light of their splendid courage and resource. I can only envy their opportunities."

Eventually, Nevinson managed to go to the Western Front to report the war. He also accompanied the expedition to the Dardanelles where he was wounded during the Gallipoli landings. His account of the evacuation of Suvla Bay in December 1915, was held up by the censor for four months. His son, the artist, Christopher Nevinson, was a pacifist and refused to become involved in combat duties, and volunteered instead to work for the Red Cross on the Western Front.

Nevinson wrote over 30 books including Women's Vote and Men (1913), Essays in Freedom and Rebellion (1921), three volumes of autobiography, Changes and Chances (1925-28), Between the Wars (1936) and Running Accompaniments (1936).

Henry and Margaret Nevinson still lived together. They used to eat separately except for Sundays. According to her biographer, Angela V. John: "Her final years were lonely ones, plagued by depression." Christopher Nevinson described their home "a cheerless uninhabited house". Henry wrote: "Children are a quiverful of arrows that pierce the parents' hearts."

In 1928 Margaret told friends that she wanted to go into a nursing home "and have done with it". She tried to drown herself in the bath. Henry Nevinson wrote to Elizabeth Robins about her health: "At present I am in great tribulation, for Mrs. Nevinson's mind is rapidly failing, and I am perplexed what is best for her. To send her to a mental home among strangers seems to me cruel, but all are urging it, partly in hopes of reducing the great expense. I am so much opposed to it that I should far rather go on spending my small savings in the hope that she may end quietly here." Margaret Nevinson died of kidney failure at her Hampstead home, 4 Downside Crescent, on 8th June 1932.

Henry married Evelyn Sharp on 18 January 1933 at Hampstead Registry Office. "Evelyn aged sixty-three married Henry, now in his seventy-seventh year." Ramsay MacDonald offered to be best man but they declined the offer as they had not approved of him becoming prime minister of a National Government. Evelyn shocked the guests by wearing a black dress for the ceremony.

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the Nevinsons' house in Hampstead was bombed and the couple moved to the vicarage at Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire. Henry Nevinson died aged 85 on 9th November, 1941. Sharp wrote in her diary: "There was a flaming red sunset right across the sky and the reflection of it was across the room." His funeral was held at Golders Green Crematorium and was followed by a memorial meeting at Caxton Hall on 11th December.

Margaret Storm Jameson told Evelyn Sharp that "you were woven into his life by memories, going back years and years" and that he had depended on her "as an anchor and centre". Maude Royden claimed that Evelyn and Henry's "happiness had lit up a room like a lamp". George Peabody Gooch added that the "greatest thing in his life was their love for each other".

Primary Sources

(1) Philip Gibbs, The Pageant of the Years (1946)

My friend Henry W. Nevinson, always the defender of liberty, always a man of fearless courage, allied himself with the women's cause and marched with them when they advanced to the House of Commons, or spoke for them when they held meetings at Caxton Hall.

I was at the Albert Hall where the Suffragettes kept up constant interruptions of a big meeting where Cabinet Ministers were present. Nevinson's blood boiled when he saw one of the stewards clench his fist and give a knock-out blow on the chin to one of the militant women. Other women were being roughly handled. Nevinson jumped from the stage box, and fought half a dozen stewards at once until they over-powered him and flung him out.

(2) In The Nation H. W. Nevinson complained about the restraints placed on him while journalists such as Philip Gibbs and Hamilton Fyfe continued to report the war without official permission (12th September, 1914)

I have served as a correspondent for nearly twenty years in many countries and under all sorts of conditions. I think I know all the tricks of the trade, and I have seen many of them practised. But I cannot foresee how any correspondent could give away his country or do the smallest public injury under these regulations, even if he wanted to. Take things as they stand. Twelve of us have been selected to accompany the British Force. It is absolutely impossible to imagine men of this experience and quality giving away our country or making dangerous revelations or mistakes, even if they stood under no regulations at all. They simply would not do it. They would rather die.

We have all engaged servants, bought horses, and weighed our kit. Everything is ready, and yet we are kept chafing here, week after week, while a war for the destiny of the world is being fought within a day's journey, and others of our colleagues are allowed to go dashing about France in motors almost up to the very front. I do not make light of their splendid courage and resource. I can only envy their opportunities. The vivid pictures they send of panic and destruction, the stories they learn from wounded and refugees, are the only accounts that the British people have been allowed to hear of the reality of the war.

(3) Angela V. John, The Life and Times of Henry Nevinson (2006)

Women's suffrage now occupied much of his spare time. Why? A cynical response might be that editors were no longer interested in him. He had a reputation as a volatile journalist, not keen to conform. Aided by admirers, he had built up an image of himself as a sturdy champion of freedom wherever in the world it might be threatened. In 1909 his Essays in Freedom appeared. What more obvious step than to espouse this on his own doorstep?

His support was also connected to his interest in Greek civilization and a belief in natural justice and fair play though he professed to be more motivated by actual examples of the denial of freedom than abstract principles. Committed to championing small nations and the oppressed, he described women as "the largest subject race in the world". Like other suffrage writers and radicals, he drew inspiration from Italian nationalism. The section on suffrage in his autobiography begins with a quote from Mazzini.

Disappointment with the illiberal Liberals also played a part. His Introduction to a pamphlet on the treatment of British political prisoners denounced forcible feeding: "If these things had happened in Italy or Russia, or had been perpetuated by Conservatives, with what noble indignation the heart of the Liberal Party would have palpitated!"

The struggle for women's suffrage was not new but with the beginning of the twentieth century it acquired greater urgency. Although large sections of the male working class remained unenfranchised and the campaign for men's voting rights had been protracted and contested, still not one single woman could vote. Like a number of progressive men, despite his age and essential Victorianism, Henry cast himself as a new man of the new century, part of the intelligentsia espousing advanced causes and envisaging a better world for all. He and other pro-suffrage men believed they could make a difference. They justified their intervention in a cause palpably not their own by arguing that, precisely because they already had the vote, they had no personal axe to grind. As men of influence in Parliament, the press, academia, commerce, the professions or other areas of power dominated by a male elite, they could get opinions heard. As a journalist Henry was also attracted to Edwardian suffrage meetings since the movement was rapidly colonizing newspaper space. Suffrage activists were superb self-publicists, delighting in the propaganda value of spectacle. But there was also a personal dimension which gave Henry an important connection to women's suffrage: his involvement with Evelyn Sharp.

In order to understand how and why Evelyn Influenced Henry, we need to consider his family life over these years. A disjunction between private morality and public politics was nothing new in British society even though generally frowned upon. Yet there was a particular irony in Henry's position since gender relations lay at the heart of the women's suffrage campaign. He was a passionate romantic involved in multiple relationships and committed to the women's movement. He trod a thin, equivocal line.

Henry made an important contribution to the winning of women's suffrage, particularly through its less glamorous and less publicized side of negotiations during the First World War. But, like a number of pro-suffrage male supporters, there was a gap between his public utterances and his personal practice. He was inclined to represent his affairs with women as inevitable given his romantic nature. His private behaviour is not easily squared with his public pronouncements and he did not seriously critique gender relations. Yet, compared to many men born in the mid-nineteenth century who also inhabited the largely male worlds of high politics, national newspapers, clubs, the military and travel in the Empire, he was remarkably sensitive and attuned to women's perceptions. He also knew what not to say. Claiming that men could "never bring the same personal & overwhelming conviction into the movement as women" helped win appreciation from both men and women. His lovers were invariably feminists who recognized that he was much more supportive than were most men they knew. And although they disagreed on most matters, women's suffrage was one subject where Henry and Margaret respected each other.

(4) H. W. Nevinson, The Daily News (12 March, 1915)

In the old days the war correspondent's rule was to ride as hard as possible to the sound of the guns. But now he moves under orders and goes by motor. It used to be said in irony that no action could begin till he came up. But now his presence is not exactly demanded, though I think the chief fear is lest the car should be a single moment delay the movement of reinforcements along the road.

(5) H. W. Nevinson, The Manchester Guardian (14th April, 1916)

After the strain of carefully organised preparations, the excitement of the final hours was extreme, but no signs of anxiety were shown. Would the sea remain calm? Would the moon remain veiled in a thin cloud? Would the brigades keep time and place? Our own guns continued firing duly till the moment for withdrawal came. Our rifles kept up an intermittent fire, and sometimes came sudden outbursts from the Turks.

Mules neighed, chains rattled, steamers hooted low, and sailor men shouted into megaphones language strong enough to carry a hundred miles. Still the enemy showed no sign of life or hearing, though he lay almost visible in the moonlight across the familiar scene of bay and plain and hills to which British soldiers have given such unaccustomed names.

So the critical hours went by slowly, and yet giving so little time for all to be done. At last the final bands of silent defenders began to come in from the nearest lines. Sappers began to come in, cutting all telephone wires and signals on their way. Some sappers came after arranging slow fuses to kindle our few abandoned stores of biscuits, bully beef, and bacon left in the bends of the shore.

Silently the staffs began to go. The officers of the beach party, who had accomplished such excellent and sleepless work, collected. With a smile they heard the distant blast of Turks still labouring at the trenches - a peculiar instance of labour lost. Just before three a pinnace took me off to one of the battleships. At half-past three the last-ditchers put off. From our familiar northern point of Suvla Bay itself, I am told, the General commanding the Ninth Army Corps was himself the last to leave, motioning his chief of staff to go first. So the Sulva expedition came to an end after more than five months of existence.

(6) H. W. Nevinson, The Daily News (10th August, 1918)

I have spent much of the day from early morning until noon walking over parts of the battlefield; having first the extraordinary experience of being able to pass in a motor-car not only over what yesterday was No Man's Land, but over the trenches of the front German system, and from my seat in the car look down on the enemy dead below. When the road became impassable by reason of the shell-holes made by our guns one could stray at large over the great deserted plain, while the guns thudded intermittently and our aeroplanes wheeled overhead.

(7) Henry Nevinson, letter to Elizabeth Robins (4th June, 1932)

At present I am in great tribulation, for Mrs. Nevinson's mind is rapidly failing, and I am perplexed what is best for her. To send her to a mental home among strangers seems to me cruel, but all are urging it, partly in hopes of reducing the great expense. I am so much opposed to it that I should far rather go on spending my small savings in the hope that she may end quietly here.