Adela Pankhurst

Adela Pankhurst, the youngest daughter of Dr. Richard Pankhurst and Emmeline Pankhurst, was born in Manchester on 19th June 1885. She had two older sisters, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst. According to Fran Abrams: "There was no great novelty to the addition of a third girl to the existing brood, and in any case this child was a sickly creature. She had weak legs and bad lungs, and for a time was not expected to live." Adela was forced to wear splints on her legs and did not learn to walk until she was three.

Adela later recalled how her father played an important role in her education: "I think I was only about six when my father - a most revered person in my existence - assured me there was no God." She was happy at her first school in Southport but did not like her experience at Manchester Girls' High School. On one occasion she tried to run away from school and home.

Richard Pankhurst, a radical lawyer, was one of the Independent Labour Party candidates in Manchester, who had been defeated in the 1895 General Election. Christabel's father died of a perforated ulcer in 1898 but his wife and her two older daughters remained active in politics.

Adela was a bright student and her teachers suggested that she should apply for an Oxford University scholarship. Emmeline Pankhurst was against the idea but the plan was only abandoned after she caught scarlet fever in 1901. Her mother sent her to Switzerland and when Adela returned to Manchester she was determined to become a teacher. Although her mother objected as she saw it as a "working-class occupation" by 1903 was working as a pupil-teacher at an elementary school in Urmston.

Emmeline Pankhurst was a member of the Manchester branch of the NUWSS. By 1903 Pankhurst had become frustrated at the NUWSS lack of success. With the help of her three daughters, Adela, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst, she formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). At first the main aim of the organisation was to recruit more working class women into the struggle for the vote.

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote.

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were arrested and charged with assault.

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. Members of the WSPU now became known as suffragettes.

Adela Pankhurst was given the task of disturbing meetings held by Winston Churchill. Another member of the WSPU, Hannah Mitchell, was with her when she was arrested while disrupting one of Churchill's political meeting: "I followed Adela who was in the grip of a big burly officer who kept telling her she ought to be smacked and set to work at the wash tubs. She grew so angry that she slapped his hand, which was as big as a ham." Adela was found guilty of assaulting a policeman. She refused to pay and was sent to Strangeways prison for seven days.

On her release Adela wrote an account of her experiences in The Labour Record: "As a teacher I had been trying for years in the case of the children with whom I had to deal to stave off the inevitable answer... I had felt the hopeless futility of my work. Now, in prison... it seemed to me that for the first time in my life I was doing something which would help."

In early 1907 she and Helen Fraser organized the WSPU campaign at the Aberdeen South by-election. Fraser later recalled: "It was winter and very cold. I met her at the station and was horrified at her breathing. I took her to lodgings and sent for the doctor, who, like me, was very critical of her being allowed to travel. She had pneumonia." The campaign was a success and the Liberal Party majority of George Birnie Esslemont was reduced from 4,000 to under 400.

Adela continued her campaign against Winston Churchill and in October 1909, she was assaulted by Liberal Party stewards in Abernethy. A few days later she arrested for throwing stones at a hall where Churchill was about to speak. While in prison she went on hunger strike. The doctor who treated Adela described her as "a slender under-sized girl five feet in height and seven stones in weight." He added that she was of a "degenerate type". She was deemed unfit for force feeding and was released from prison. many."

Sylvia Pankhurst argued in The Suffrage Movement that Adela did not get the credit she deserved for the role she played in the campaign: "The desire was a reaction from the knowledge that though a brilliant speaker and one of the hardest workers in the movement, she was often regarded with more disapproval than approbation by Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel, and was the subject of a sharper criticism than the other organisers had to face."

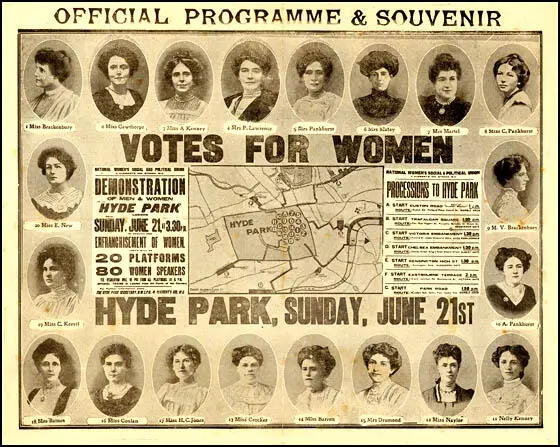

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

Adela Pankhurst became concerned about the increase in the violence used by the Women's Social and Political Union. She later told fellow member, Helen Fraser: "I knew all too well that after 1910 we were rapidly losing ground. I even tried to tell Christabel this was the case, but unfortunately she took it amiss." After arguing with Emmeline Pankhurst about this issue she left the WSPU in October 1911. Sylvia Pankhurst was also critical of this new militancy. Christabel Pankhurst replied that "I would not care if you were multiplied by a hundred, but one of Adela is too many."

In 1912 Adela embarked on a diploma course at Studley Horticultural College in Worcestershire. The following year she found employment as head gardener with a family in Bath. Adela, whose health was not very good, struggled with this work and in 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst, who was worried that her daughter would criticise the WSPU in public, agreed to pay for a one-way ticket to Australia.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Adela, like her sister Sylvia Pankhurst, completely rejected this strategy and in Australia she joined with Vida Goldstein in the campaign against the First World War. Adela believed that her actions were true to her father's belief in international socialism. Adela and Goldstein established the Australian Women's Peace Army. She wrote to Sylvia that like her she was "carrying out her father's work". Emmeline Pankhurst completely rejected this approach and told Sylvia that she was "ashamed to know where you and Adela stand." Edgar Ross, a fellow campaigner against the war in Melbourne later recalled: "What I remember most about her was her courage. She would stand, unfearing, in front of jingo-mad soldiers heckling her when speaking on the platform."

On 30th September 1917, Adela married Tom Walsh, a widower with three children. He was also an organiser for the Seamen's Union of Australia. Six days later she was sentenced to four months' imprisonment for a series of public order offences carried out during demonstrations against conscription. Adela was released in January 1918.

In 1921 Adela and Tom became members of the executive committee of the Australian Communist Party. However, they did not remain party members for long and they began to drift to the right. In 1928 she founded the Australian Women's Guild of Empire. It was based on the Women's Guild of Empire, an organisation formed by Flora Drummond in London. The Women's Guild initially raised money for working class women and children hit by the Great Depression. It advocated the need for industrial cooperation and criticised trade union activity. It was also a patriotic organisation which developed strong anti-communist views.

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003): "She (Adela Pankhurst) saw herself as a champion of the poor, even though her new organisation condemned working mothers, abortion, contraception, communism and trade unions. When she made a tour of the Australian coalfields to attack the unions during a lock-out, she talked mostly about how the children of the miners were suffering. She used her guild to start a welfare agency for families struggling in industrial areas."

In addition to her three step-daughters, Adela had five children of her own - Richard named after her father, Sylvia after her sister, Christian, Ursula and Faith, who died soon after she was born. Ursula later recalled: "We children never felt neglected and felt nothing for her but love, respect and a strange desire to protect her." Emmeline Pankhurst never saw any of Adela's children. However, she also moved sharply to the right in the 1920s and a few weeks before her death in 1928, she wrote to Adela expressing regret for the long rift between them.

Adela continued to drift to the right and showed some sympathy for what Adolf Hitler was doing in Nazi Germany. On the outbreak of the Second World War she was asked to resign from the Australian Women's Guild of Empire. The following month she caused a stir when she and Tom Walsh, went on a goodwill mission to Japan. In March 1942 she was interned for her pro-Japanese views. She was released after more than a year in custody, just before her husband's death in April 1943.

After the war Adela did not play an active role in politics. In 1949 she told her friend Helen Fraser that she had been persecuted because of her hostility to communism: "So long did I warn my supporters that co-operation with Russia and all those who supported the Bolsheviks was the way to disaster and I was ruined and interned for my pains... Communism has not brought home the bacon... Taken on achievement, Fascism did very much better while it lasted. Officially we don't admit this but actually I believe most people who are interested know it perfectly well"

Adela Pankhurst died in Australia on 23rd May, 1961.

Primary Sources

(1) Adela Pankhurst, The Labour Record (November, 1906)

As a teacher I had been trying for years in the case of the children with whom I had to deal to stave off the inevitable answer... I had felt the hopeless futility of my work. Now, in prison... it seemed to me that for the first time in my life I was doing something which would help.

(2) Adela Pankhurst, Votes for Women (November, 1909)

The cold was intense. I suffered from hunger nearly the whole time and from great pain for two days, especially at night. I am filled with admiration and wonder at the courage and endurance of those who in English prisons have gone through under conditions which make ours seem almost nothing.

(3) Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffrage Movement (1931)

The desire was a reaction from the knowledge that though a brilliant speaker and one of the hardest workers in the movement, she was often regarded with more disapproval than approbation by Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel, and was the subject of a sharper criticism than the other organisers had to face.

(4) Fran Abrams, Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003)

She (Adela Pankhurst) saw herself as a champion of the poor, even though her new organisation condemned working mothers, abortion, contraception, communism and trade unions. When she made a tour of the Australian coalfields to attack the unions during a lock-out, she talked mostly about how the children of the miners were suffering. She used her guild to start a welfare agency for families struggling in industrial areas. And she still lived by the suffragette slogan, "Deeds not Words". Arriving at the scene of a strike by unemployed workers on government work programmes, she was taunted by a communist leader who shouted: "You wouldn't do this sort of work yourself." Adela and her secretary, Enid Metcalfe, put on rubber boots, took up spades and started digging. On another occasion a group of striking seamen threw a bucket of water over her. Adela, unmoved, simply joked that as a sailor's wife she could hardly be expected to be afraid of water.