Annie Kenney

Annie Kenney, the daughter of Nelson Horatio Kenney and Anne Wood, was born at Springhead, a suburban area of Saddleworth, on 13th September 1879. Annie's mother had eleven children and worked with her husband in the Oldham textile industry. Annie was born prematurely and was not expected to survive. When Annie reached the age of ten she began work in a local cotton mill. Soon afterwards a whirling bobbin tore off one of her fingers.

At the age of thirteen Kenney became a full-time worker at the mill and had to get up at five in the morning to start at six, and finished work at 5.30 p.m. On arriving home she was expected to help with washing, cooking and scrubbing floors. If she had any free time she played with her dolls.

Annie later recalled that her "father never seemed to have any confidence in his children, he had very little in himself". Although Annie received very little education but her mother encouraged her to read and as a teenager she developed a strong interest in literature. She later recalled: "Mother allowed us great freedom of expression on all subjects.... I grew up with a smattering of knowledge on many questions." Annie was especially impressed by authors such as Tom Paine, Robert Blatchford,Edward Carpenter and Walt Whitman. After being inspired by an article she read in Robert Blatchford's radical journal, The Clarion, Annie joined the local branch of the Independent Labour Party.

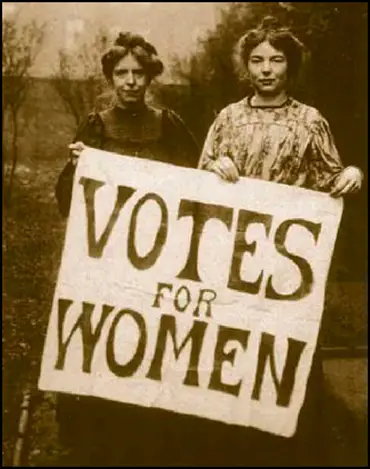

At an Independent Labour Party meeting in 1905, Annie Kenney and her sister, Jessie Kenney, heard Christabel Pankhurst speak on the subject of women's rights. Annie was extremely impressed with the content of the speech and the two women soon became close friends. Annie decided to join the recently formed Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

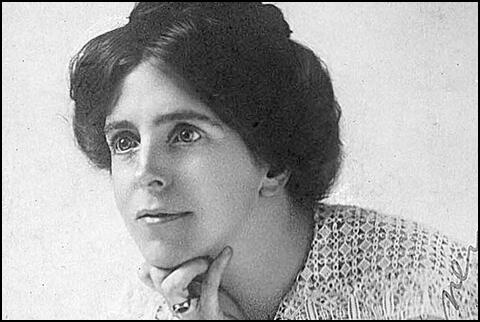

Emmeline Pankhurst commented: "There was something about Annie that touched my heart. She was very simple and seemed to have a whole-hearted faith in the goodness of everybody that she met." Christabel Pankhurst added: "She was eager and impulsive in manner, with a thin, haggard face, and restless knotted hands, from one of which a finger had been torn by the machinery it was her work to attend. Her abundant, loosely dressed golden hair was the most youthful looking thing about her... The wild, distraught expression, apt to occasion solicitude, was found on better acquaintance to be less common than a bubbling merriment, in which the crow's feet wrinkled quaintly about a pair of twinkling, bright blue eyes."

The WSPU was often accused of being an organisation that existed to serve the middle and upper classes. As Annie Kenney was one of the organizations few working class members, when the WSPU decided to open a branch in the East End, she was asked to leave the mill and become a full-time worker for the organisation. Annie joined Sylvia Pankhurst in London and they gradually began to persuade working-class women to join the WSPU.

Jessie Kenney also moved to the capital and become the private secretary to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "By the time she was 21 she was the Women's Social and Political Union's youngest organizer, working from Clement's Inn, arranging meetings, publicity stunts, interruptions of cabinet ministers' meetings and, as time passed, acts of militancy." She had different skills from her sister. Sylvia Pankhurst pointed out that Jessie was "eager in manner as her sister Annie, with more system and less pathos, and without any gift of platform speech."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence argued that Annie was a devoted follower of Christabel Pankhurst. "Annie's... devotion took the form of unquestioning faith and absolute obedience ... Just as no ordinary Christian can find that perfect freedom in complete surrender, so no ordinary individual could have given what Annie gave - the surrender of her whole personality to Christabel." Annie admitted that: "For the first few years the militant movement was more like a religious revival than a political movement. It stirred the emotions, it aroused passions, it awakened the human chord which responds to the battle-call of freedom ... the one thing demanded was loyalty to policy and unselfish devotion to the cause."

On 13th October 1905, Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting, the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle, a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were arrested and charged with assault.

Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant (1924) she described what it was like to be in prison with Christabel: "Being my first visit to jail, the newness of the life numbed me. I do remember the plank bed, the skilly, the prison clothes. I also remember going to church and sitting next to Christabel, who looked very coy and pretty in her prison cap ... I scarcely ate anything all the time I was in prison, and Christabel told me later that she was glad when she saw the back of me, it worried her to see me looking pale and vacant.

On her release from prison Emmeline Pankhurst sent her to meet the journalist, William Stead. According to Fran Abrams: "Perhaps Emmeline knew of Stead's fondness for young girls, which Sylvia experienced too. On one occasion Annie had to appeal to Emmeline to ask him not to kiss her when she went to his office. But Annie liked Stead, and he quickly became a father figure. Before their first meeting was over she was sitting on the arm of his chair, telling him all about her life. He responded by telling her she must come to him if she was ever lonely or in trouble. Later he even let her use a room in his house in Smith Square to rest during Westminster lobbies and demonstrations, and he lent her £25 to help her organise her first big London meeting." Annie became very close to Stead and used to spend time with him at his house on Hayling Island in Hampshire. In one article Stead argued that Annie Kenney was the new Josephine Butler.

In May 1906 Annie, dressed as the sterotypical mill girl in clogs and shawl, she led a group of women to the home of Herbert Asquith, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. After ringing the bell incessantly, she was arrested and sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. On her release she went on holiday with Christabel Pankhurst and Mary Gawthorpe.

In 1907 Annie Kenney was appointed WSPU organiser at a salary of £2 a week, in the West of England. She was based in Bristol. It was not long before she recruited Victoria Lidiard, a photographer assistant, who became one of her assistants. The following year she met Mary Blathwayt at a WSPU meeting in Bath. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), claims that Blathwayt had fallen "under her spell and gave her a rose". Over the next few years she was to spend a lot of time at Blathwayt's home at Eagle House near Batheaston "where, for the first time, she began to learn French, to play tennis, to swim, to ride and to drive."

Kenney was to go to prison several times during the next six years. William Stead compared her to Joan of Arc, whereas Josephine Butler described her as: "A woman of refinement and of delicacy of manner and of speech. Her physique is slender, and she is intensively nervous and high strung. She vibrates like a harpstring to every story of oppression."

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond, Edith New and Gladice Keevil. (x)

(x) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 95

In March 1910, Annie and Christabel Pankhurst went on holiday together in Guernsey. A fellow member of the WSPU, Teresa Billington-Greig claimed that Annie was "emotionally possessed by Christabel". However, Mary Blathwayt, who spent a lot of time with Annie during this period argued that it was Annie who was the dominating personality as she had a "wonderful influence over people".

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that Annie Kenney had a series of romantic attachments with other suffragettes: "The relationship (with Christabel Pankhurst) would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments. One historian who argues that Annie must have had sexual feelings for other women adds that lesbianism was barely recognised at the time. Such relationships, even when they involved sharing beds, excited little comment. Already, Christabel had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family - according to Sylvia."

Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote on 7th September 1910 that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account. The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else."

Teresa Billington-Greig has argued that Annie was also very close to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. "It is true that there was an immediate and strong emotional attraction between Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Annie Kenney... indeed so emotional and so openly paraded that it frightened me. I saw it as something unbalanced and primitive and possibly dangerous to the movement ... but the emotional obsession died out and the partnership... persisted for many years."

Annie admitted in her autobiography that suffragettes developed a different set of values to other women at the time: "The changed life into which most of us entered was a revolution in itself. No home life, no one to say what we should do or what we should not do, no family ties, we were free and alone in a great brilliant city, scores of young women scarcely out of their teens met together in a revolutionary movement, outlaws or breakers of laws, independent of everything and everybody, fearless and self-confident."

When Christabel Pankhurst fled to France to avoid arrest in 1912, Annie was put in charge of the WSPU in London. She appointed Rachel Barrett as her assistant. Every week Annie travelled to Paris to receive Christabel's latest orders. Fran Abrams has pointed out: "It was the start of a cloak-and-dagger existence that lasted for more than two years. Each Friday, heavily disguised, Annie would take the boat-train via La Havre. Sundays were devoted to work but on Saturdays the two would walk along the Seine or visit the Bois de Boulogne. Annie took instructions from Christabel on every little point - which organiser should be placed where, circular letters, fund-raising, lobbying MPs... During the week Annie worked all day at the union's Clement's Inn headquarters, then met militants at her flat at midnight to discuss illegal actions. Christabel had ordered an escalation of militancy, including the burning of empty houses, and it fell to Annie to organise these raids. She did not enjoy this work, nor did she agree with it. She did it because Christabel asked her to, she said later."

In 1912 the WSPU began a campaign to destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. By December, the government claimed that over 5,000 letters had been damaged by the WSPU. The WSPU also began a new arson campaign. Under the orders of Christabel Pankhurst, attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote.

The militant campaign was directed from Annie's flat that she shared with Jessie Kenney and another one of her lovers, Rachel Barrett. She asked Elizabeth Robins to witness a letter that Christabel Pankhurst sent her in which she gave her control of the WSPU in London.

Annie Kenney was charged with "incitement to riot" in April 1913. She was found guilty at the Old Bailey and was sentenced to eighteen months in Maidstone Prison. She decided that Grace Roe should now became head of operations in London. She immediately went on hunger strike and became the first suffragette to be released under the provisions of the Cat and Mouse Act. Kenney went into hiding until she was caught once again and returned to prison. That summer she escaped to France during a respite and went to live with Christabel Pankhurst in Deauville.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 ended the WSPU militant campaign for the vote. Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

Fran Abrams, the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued: "Annie, now becoming increasingly uncomfortable with Christabel's autocratic style, must have shown some hint of her true feelings because she was soon asked to leave the country. One of the leaders of the movement should be safe in case of invasion, Christabel said."

Annie Kenney was sent to the United States. She did not enjoy the experience and when Christabel Pankhurst arrived in the country to make a speech at Carnegie Hall urging Americans to enter the war on the side of the Allies, Kenney managed to persuade Christabel to allow her to come home.

In 1915 the WSPU sent Annie Kenney to Australia to help the prime minister, William Hughes, in a referendum campaign on conscription. On her return she worked with David Lloyd George to help find female recruits for the munition factories. She was also involved in organizing an Anti-Bolshevist campaign against strikes.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Kenney helped Christabel Pankhurst in her election campaign in Smethwick. Despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, Christabel lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party.

In 1918 Annie Kenney went to live with Grace Roe in St Leonards-on-Sea in Sussex. The two women became followers of Annie Besant, who was the leader of the Theosophy movement in Britain. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), Grace Roe later "remarked on the part played by theosophists behind the scenes of the militant suffrage movement. She made the point that theosophy not only gave a spiritual dimension to their lives but, cutting across class, put people in touch with each other who would have been unlikely otherwise to meet."

While staying with her sister on the Isle of Arran, she met James Taylor (1893-1977). Mary Blathwayt claims in her diary that Taylor "is quite simple like Annie and has a divine singing voice." The couple were married in April 1920 at St Cuthbert's Church. They moved to Letchworth, where Taylor was appointed maintenance engineer at St Christopher's School. A son, Warwick Kenney Taylor, was born in February, 1921. Her sister, Jessie Kenney, worked as a steward on a cruise liner but used Annie's home as a base.

Kenney lost interest in politics but she continued to keep in contact with Christabel Pankhurst. In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant (1924) she wrote: "There is a cord between Christabel and me that nothing can break - the cord of love... We started militancy side by side and we stood together until victory was won."

James Taylor claims that his wife never really recovered from her hunger strikes and, after a long, and steady decline, she died of diabetes at the Lister Hospital in Hitchen on 9th July, 1953.

Primary Sources

(1) Annie Kenney was born in Lancashire in 1879. In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant, she describes her close relationship with her mother. page 21

My mother was a wonderful woman. Her theory was: See the best in anyone and the worse will gradually fall away. Be kind to others, tolerant and sympathetic. We were never allowed in her hearing to say either unkind things about others or to abuse others in any way. She was ever ready to lend a patient ear to other people's troubles, while at the same time showing a remarkable fortitude in her own.

Our home-life was happy. Our one trouble was that we had to retire much earlier than the other children of the village… I can still see our home with its bright, roaring rosy fire, and all the children, including myself, sitting on the window-sill watching the lights of the cotton factory, a few miles away, gradually going out. Those lights were our signal to retire… On Sunday evenings mother read us stories. They all seemed to be about London life among the poor...

Father never seemed to have any confidence in his children, and he had very little in himself. Had he possessed this essential quality, perhaps the whole course of our lives would have been changed. My mother always said she ought to have been the man and father the woman...

Never had she an evening in which to read or to cultivate her mind. It was work, work, work: until at midnight she would still be at work darning stockings. It did not seem to me fair, and the sense of the unfairness of it to mother has never ceased to rankle...

My mother allowed us great freedom of expression on all subjects, whether it was dancing or the Athanasian Creed, Spiritualism, Haeckel, Walt Whitman, Batchford, or Paine, I grew up with a smattering of knowledge on many questions.

(2) Annie Kenney wrote about her school experiences in her autobiography, Memories of a Militant.

I went to the village school when I was five. When I was ten years of age a change came into my life. My mother announced to me that I was to work in a factory. I was to join the army of half-timers; to work in the factory half the day and attend school the other half. I received the news with mixed feelings. I was glad to escape the hated school lessons, which were a burden to me, but I had a fear of the new life. When I arrived at the factory I was met by a group of girls… who stared at me. Every new girl was critically examined by the older girls. Your clogs were examined; thick or thin made a difference; your petticoat, your pinafore, the quality, the colour, stamped you accordingly in the eyes of these girl students of ten and thirteen.

(3) Annie Kenney joined the WSPU after hearing Christabel Pankhurst and Teresa Billington speak on Women's Suffrage in Manchester in 1905.

The Oldham Trades Council invited Christabel Pankhurst and Teresa Billington to speak on Women's Suffrage. I had never heard of 'Votes for Women'. Politics did not interest me in the least. Miss Pankhurst was more hesitating, more nervous than Miss Billington. She impressed me, though. She was more impersonal and full of zeal. Miss Billington used a sledge-hammer of logic and cold reason… When the meeting was over I drifted towards Miss Pankhurst. Before I knew what I done I had promised to organize a meeting for Miss Pankhurst among factory-women of Oldham.

(4) In 1906 Annie Kenney joined Sylvia Pankhurst in London to help organize the WSPU in the area. Sylvia Pankhurst later wrote about this in her book The Suffrage Movement.

Annie Kenney had come with instructions to rouse London. It was easy for me to decide that we should follow all the popular movements by holding a meeting in Trafalgar Square… I went at once to Keir Hardie for advice. He told us to engage the Caxton Hall for our meeting, and promised to induce a friend to pay for the hall and the handbills to advertise it. The press began to hover around the house; the Daily Mail had already christened us the 'Suffragettes'.

(5) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, My Part in a Changing World (1938)

Christabel's devotee (Annie Kenney) in a sense that was mystical... she neither gave nor looked to receive any expression of personal tenderness: her devotion took the form of unquestioning faith and absolute obedience ... Just as no ordinary Christian can find that perfect freedom in complete surrender, so no ordinary individual could have given what Annie gave - the surrender of her whole personality to Christabel. That surrender endowed her with fearlessness and power that was not self limited and was therefore incalculable.

(6) Christabel Pankhurst, Unshackled: the Story of how we Won the Vote (1959)

She was eager and impulsive in manner, with a thin, haggard face, and restless knotted hands, from one of which a finger had been torn by the machinery it was her work to attend. Her abundant, loosely dressed golden hair was the most youthful looking thing about her... The wild, distraught expression, apt to occasion solicitude, was found on better acquaintance to be less common than a bubbling merriment, in which the crow's feet wrinkled quaintly about a pair of twinkling, bright blue eyes.

(7) Fran Abrams, Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003)

The relationship would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments. One historian who argues that Annie must have had sexual feelings for other women adds that lesbianism was barely recognised at the time. Such relationships, even when they involved sharing beds, excited little comment Already, Christabel had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family - according to Sylvia.

Christabel was emphatically not a woman who let her emotions run away with her, and she did not do so in Annie's case. But their first meeting set a pattern that would govern every sphere of Annie's existence for the next fifteen years.

(8) Annie Kenney, Memories of a Militant (1924)

The changed life into which most of us entered was a revolution in itself. No home life, no one to say what we should do or what we should not do, no family ties, we were free and alone in a great brilliant city, scores of young women scarcely out of their teens met together in a revolutionary movement, outlaws or breakers of laws, independent of everything and everybody, fearless and self-confident...

It was an unwritten rule that there should be no concerts, no theatres, no smoking; work, and sleep to prepare us for more work, was the unwritten order of the day.

(9) After joining the WSPU Annie Kenney moved to London to work as a full-time organizer. On one occasion she was asked to represent the WSPU at a meeting with Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Conservative Party.

Lady Balfour took me to see Arthur Balfour privately. When we arrived he asked me to tell him what I thought he could do for us. I had a long talk with him… There he sat in age armchair, his long spidery legs stretched out… He constantly sniffed at a small bottle. I wondered what it contained and thought the conversation might be upsetting him… It was time to go and he had not committed himself any more than I expected he would.

(10) The Manchester Guardian (16th October, 1905)

Inspector Mather said he was on duty on Friday night, and at 8.50 visited the Free-trade Hall when the Liberal meeting was in progress. Police assistance was called for during the meeting, and he was present when these ladies were ejected. Superintendent Watson asked them to behave as ladies should, and not create further disturbance. They were then at liberty to leave. Miss Pankhurst, however, turned and spat in the Superintendent's face, repeating the same conduct by spitting in the witness's face, and also striking him in the mouth... On the way to the Detective Office, Miss Kenney, in clinging to her friend, trod upon her skirt, and the garment was left behind.

(11) The Manchester Evening Chronicle described what happened at the Liberal Party meeting at the Free Town Hall on 20th October 1905.

Miss Christabel Pankhurst and Miss Annie Kenney were ejected and later arrested for obstruction outside the building. At the police court Miss Pankhurst was fined half a guinea for assaulting the police officers by hitting them in the mouth and spitting in their faces, and five shillings for obstruction, or in default seven days. Miss Kenney was fined five shillings, or three days. Rather than pay the fine the ladies elected to undergo the imprisonment.

Miss Kenney was released on Monday morning. Miss Pankhurst period expired this morning. By seven o'clock about two hundred people had collected outside the gates of Strangeways Gaol. When Miss Christabel appeared she was hailed with a great cheer and instantly surrounded by a host of male and female admirers. The first to greet and embrace the prisoner was her mother, Miss Pankhurst. Miss Pankhurst fell into the arms of her mother, and the two wept for joy after having been parted for a whole week. As soon as she could break away from her admirers Miss Pankhurst called out, "I will go in again for the same cause. Don't forget the vote for women."

(12) In her book Memories of a Militant, Annie Kenney explained the use of the hunger strike.

In 1909 Wallace Dunlop went to prison and defied the long sentences that were being given by adopting the hunger-strike. 'Release or Death' was her motto. From that day, July 5th, 1909, the hunger-strike was the greatest weapon we possessed against the Government… before long all Suffragette prisoners were on hunger-strike, so the threat to pass long sentences on us had failed. Sentences grew shorter.

(13) Fran Abrams, Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003)

It was the start of a cloak-and-dagger existence that lasted for more than two years. Each Friday, heavily disguised, Annie would take the boat-train via La Havre. Sundays were devoted to work but on Saturdays the two would walk along the Seine or visit the Bois de Boulogne. Annie took instructions from Christabel on every little point - which organiser should be placed where, circular letters, fund-raising, lobbying MPs. When she arrived back in London a bulky letter would already be on its way to her with yet more instructions. There was such resentment within the union about Annie's new position that she earned herself the nickname "Christabel's Blotting Paper". Annie found this amusing, and took to signing her letters to Christabel, "The Blotter".

During the week Annie worked all day at the union's Clement's Inn headquarters, then met militants at her flat at midnight to discuss illegal actions. Christabel had ordered an escalation of militancy, including the burning of empty houses, and it fell to Annie to organise these raids. She did not enjoy this work, nor did she agree with it. She did it because Christabel asked her to, she said later. None the less, it fell to her to ensure that each arsonist left home with the proper equipment - cotton wool, a small bottle of paraffin, wood shavings and matches. "Combustibles" were stored by Annie in hiding places from where they could be retrieved when needed, and a sympathetic analytical chemist, Edwy Clayton, was engaged to advise on suitable places for attack. In addition to supplying a list of government offices, cotton mills and other buildings, he carried out experiments for the women on chemicals suitable for making explosives. Annie was very upset when he was later arrested and convicted of conspiracy on the basis of papers he had sent to her sister Jessie.

The fun was going out of the movement for Annie. Christabel had left a gap in her life, and the departure of the Pethick-Lawrences soon afterwards in a dispute over the direction of the union was a further blow. Annie was forced to choose between two people she loved more than any others - Christabel and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. She followed Christabel, as she always had.

(14) Annie Kenney experienced the Cat and Mouse Act for the first time in April 1912. She explained what happened in her autobiography, Memories of a Militant.

I had as my visitors the matron, the Governor, the doctor, the clergyman, and the visiting magistrate. They all asked me to eat and drink, but nothing would tempt me. The matron, the doctor and I became good friends. The doctor was ever so kind and did his best to persuade me to have fruit, but fruit was no use to me. "I must be out in three days, doctor, or I'll die on your hands!" And the good doctor did not want a death. In three days the gates were opened… Mrs. Brackenbury lent us her house at 2 Camden Hill Square. We called it 'Mouse Castle'. All the mice went there from prison and were nursed back to health and prepared for further danger work… When I recovered I was re-arrested.

(14a) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (23rd May, 1908)

A most perfect day and about fifty people came... Annie Kenney won the admiration of everyone by her speech. We laid down matting and put chairs on tennis court and after the speech we had tea on front lawn. Everything went perfectly except for Annie Kenney's voice. She strained it at Peckham and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence took her to a specialist who told her to be careful; now at Plymouth she has addressed thousands of people and has strained it very much.

(14b) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (18th November, 1908)

The London papers have account of the row, and the Bath papers are horrified, especially the liberal Herald. About 200 hooligans made a rush from the back after the hall, being full, was supposed to be closed... Mary said it was "a grand advertisement" for them. Clara Codd was not allowed to speak but the chairman Annie said everything to the purpose as she always does and the reporters have put it all in. When the platform was about to be rushed they broke up the meeting and got some of the ladies into a smaller room where they spoke... Annie was begged to go out by the back, but she said she would not sneak out like a Cabinet Minister. The police with difficulty protected our poor man from Bence's with the fly and our four got off safely. We read Clara who walked was sadly hustled and the police got her party into the York House Mews.

(15) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (8th September, 1909)

This morning I posted the following to the Sec. 4 Clement's Inn. "Dear Madam, with great reluctance I am writing to ask that my name may be taken off the list as a Member of the W.S.P.U. Society. When I signed the membership paper, I thoroughly approved of the methods then used. Since then there has been personal violence and stone throwing which might injure innocent people. When asked by acquaintances what I think of these things I am unable to say that I approve, and people of my village who have hitherto been full of admiration for the "Suffragettes" are now feeling very differently. I shall continue to do what I can to help, but I cannot conscientiously say now that I approve the methods used by several of the members... Later on Linley wrote to Christabel Parkhurst expressing something of the same views and he said how could he again be seen driving Elsie and Vera. They seem to have behaved very badly.

(5) Mary Blathwayt, diary entry (13th May, 1908)

This afternoon I helped Annie Kenney make her plans for a West of England campaign, I wrote out lists of towns and dates which are to be sent to Mrs. Pankhurst and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence. This evening Miss Howey went round the town with some steps, and I went with her. And when we came to a crowd she got onto the steps and shouted "Keep the Liberal out. Votes for Women".

(6) Mary Blathwayt, diary entry (19th June, 1908)

This evening Annie Kenney told us some things about prison. The arrangements there are very bad indeed, all food has to be carried to the mouth in fingers, no spoon or fork is allowed. For breakfast they have dry bread and some very nasty tea. Dinner two potatoes and a piece of meat; which must be held in the fingers. The sanitary arrangements are very bad indeed. The treatment makes bad women worse, and many go mad.

(14c) Annie Kenney, Memories of a Militant (1924)

It was in this year (1907) that I was made Bristol organiser. I had not been in Bristol long when I took on the whole of the West of England, also Devonshire and Cornwall. There is not a city and scarcely a town that I have not spoken in, from Bath to Land's End. The happiest days of organising were those I spent in the West of England.

Bristol and Bath stand out most. The members in those two cities were wonderful workers; they worked night and day. I had not one voluntary worker, I had scores. I trained speaker after speaker.

It would be futile to mention other names, they were all wonderful to me. There is just one I should like to mention, that of the late Colonel Blathwayt. He and Mrs. Blathwayt, of Eagle House, Batheaston treated me as though I were one of their own family. All my week-ends I spent under their hospitable roof. They also gave hospitality to the numerous speakers who came to the centre.

(15) Annie Kenney agreed to support the WSPU policy on the First World War. She explained her views in Memories of a Militant,.

Orders came from Christabel Pankhurst in Paris: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war.

(16) In her book Memories of a Militant, Annie Kenney described the proposals to give women the vote.

In 1917 the question of granting the vote to women was discussed in Parliament. It was admitted by friend and foe that British women had played and were playing a unique part in the war… There was great rejoicing among all sections of women. What a relief to think that once peace was declared abroad peace on a modest scale would be declared at home. The agitation was at last drawing to a close…On February 6th, 1918, Royal assent was given to the "Representation of the People Act." Women were voters. And so my Suffrage pilgrimage was ended… I left the Movement, financially, as I joined it, penniless. Though I had no money I had reaped a rich harvest of joy, laughter, romance, companionship, and experience that no money can buy.

(17) Vanessa Thorpe and Alec Marsh, The Observer (11th June 2000)

Entries in the diary of a suffragette have revealed that key members of the Votes For Women movement led a promiscuous lesbian lifestyle.

The diaries of supporter Mary Blathwayt, kept from 1908 to 1913, show how complicated sexual liaisons - involving the Pankhurst family and others at the core of the militant organisation - created rivalries that threatened discord.

"Mary, who had been something of a favourite, often wrote quite bluntly about the situation. It does sound as if she was occasionally quite jealous," said Professor Martin Pugh, an expert on the history of the movement, who came across the relevant and explicit pages in Blathwayt's little-known diary.

"This part of the diary puts the whole campaign in a truer perspective," he added. "All these women were under an enormous amount of pressure from around 1912, while the Home Secretary was trying to suppress their activities."

Pugh, of Liverpool John Moores University, said the tensions felt, both physically and psychologically, meant the activists had to find sus taining relationships within their own ranks.

Emmeline Pankhurst and her three daughters, Sylvia, Christabel and Adela, were the leading figures in the battle to win votes for women. Founding the hardline Women's Social and Political Union in 1903, Mrs Pankhurst, as she was popularly known, went to prison 15 times for her political views and had a close relationship with the lesbian composer Ethel Smyth for many years following the death of her husband Richard in 1898.

"Dame Ethel had realised early on in life that she loved women not men and was fairly bold about things. They were often in Holloway together and shared a cell," said Pugh.

Members of the union were social pariahs and the butt of music-hall jokes, but they were also criminals. Under the slogan Votes for Women and Chastity for Men, they bombed and set fire to churches and stations, threw bricks through windows, cut telegraph wires and tied themselves to railings.

"This was a period in which these women were carrying out something like guerrilla war - they felt they were engaging in battle with the Home Secretary, who was using all the tools of the state to oppress them," said Pugh, who is researching a biography of the Pankhurst family.

Christabel was the most classically beautiful of the Pankhurst daughters and was the focus of a rash of "crushes" across the movement. Pugh now believes she was briefly involved with Mary Blathwayt who, in her turn, was probably supplanted by Annie Kenney, a working-class activist from Oldham.

"Christabel was an object of desire for several suffragettes," he said. "She was a very striking woman."

Many of the short-lived sexual couplings referred to in the diary took place in the Blathwayt family's Eagle House home in Batheaston, near Bath.

Kenney's frequent visits to Eagle House, and to the family's Bristol lodgings, receive most scrutiny from Mary Blathwayt. Pugh's research shows that her name can now be linked to up to 10 other suffragettes.

"Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, "Annie slept with someone else again last night," or "There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning," said Pugh. "But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else."

Kenney, organiser for the South West, volunteered to join the suffragettes after hearing Christabel Pankhurst speak at a rally in 1905. The two were sent to prison together that year after disrupting a public meeting and had an intimate friendship for several years until Christabel became involved with another woman, Grace Roe.

While the affairs and one-night-stands at Eagle House provoked competitive rivalries, it is also clear they held the movement together. Many of the relationships provided emotional support for members of a group isolated from the rest of society.

"Biographers, while acknowledging a small lesbian element in the movement, have all skirted around the issue," said Pugh. "For those times the matter-of-fact tone Blathwayt adopts about the affairs did surprise me."

The union suspended its militant activities to help the war effort in 1914 and women over 30 gained the vote in 1918. Equal suffrage was finally achieved in 1930.