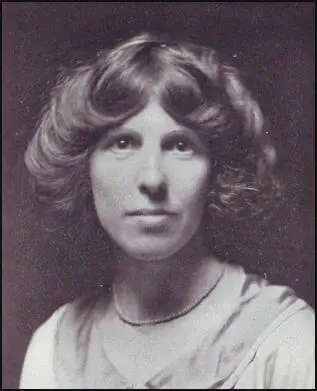

Jessie Kenney

Jessie Kenney, the daughter of Nelson Horatio Kenney (1849-1912) and Anne Wood (1852-1905), was born at Shelderslow, near Oldham, on 1st April 1887. Jessie was the ninth of eleven children. (1)

Jesse's parents had married in 1873 when he was 23 and she was 21. Anne worked in a cotton card room and Nelson was a "self-actor minder", meaning that he managed his own spinning mules at the Grotten Hollow factory. (2)

The older children started work at the age of ten. However, the income brought home by her older siblings meant that Kenney was able to remain in school for longer and did not start work until she was thirteen. Jessie and her older sister Jane planned to become teachers and hoped to set up their own school. After leaving formal education, she attended night school to further her education alongside working in a local factory. (3)

Jessie Kenney: Home Life

When Jessie reached the age of 13 she began work in a local cotton mill. However, she continued to study at evening classes, which included taking typing lessons. Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out "like many families of those days circumstances depressed them into poverty, but the Kenney family came from a home where there was a basis of culture and the ideals of a cultivated life". (4)

According to her sister Annie Kenney: "My mother was a wonderful woman. Her theory was: See the best in anyone and the worse will gradually fall away. Be kind to others, tolerant and sympathetic. We were never allowed in her hearing to say either unkind things about others or to abuse others in any way. She was ever ready to lend a patient ear to other people's troubles, while at the same time showing a remarkable fortitude in her own.... Father never seemed to have any confidence in his children, and he had very little in himself. Had he possessed this essential quality, perhaps the whole course of our lives would have been changed. My mother always said she ought to have been the man and father the woman." (5)

Anne Kenney was the main figure in most of the children's lives and encouraged them to be ambitious. Horatio Kenney was kindly and scrupulously honest, but mismanaged money and occasionally drank too much. (6) He exhibited birds and animals at shows, and his son Rowland Kenney recalled that "small livestock were… part of the blood and bone of my childhood's existence". (7)

Reginald, the eldest son, is probably the young man at the back, on the right. Rowland,

is the other young man in the back row. The two young boys, Herbert and Harold,

are sitting in front of their parents, Horatio Nelson Kenney and Ann Kenney.

The Kenney family were members of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and her brother Rowland Kenney (1882-1961) became an important socialist journalist who eventually became editor of the Daily Herald. (8) The children were encouraged to read the works of Thomas Paine, Robert Blatchford and Walt Whitman and used to read the socialist newspaper, The Clarion. (9)

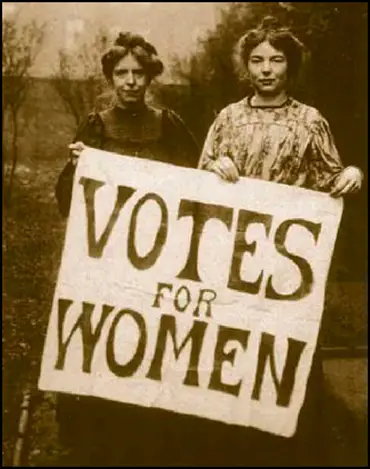

Women's Social and Political Union

Anne Kenney was only 53 when she died in January 1905. Jessie and six of her siblings were still living at home at the time. Soon afterwards Jessie and her older sister, Annie Kenney, went to a meeting of the Oldham Trades Council organised by the ILP, that was addressed by Christabel Pankhurst and Teresa Billington-Greig. (10)

Annie later wrote an account of this meeting: "I had never heard about votes for women... Miss Billington used a sledge-hammer of logic and cold reason - she gave me the impression that she was a good debater. I liked Christabel Pankhurst: I was afraid of Teresa Billington... It was like a table where two courses were being served, one hot, the other cold. I found myself plate in hand, where the hot course was being served." (11)

Jessie and Annie were so impressed by these speeches that they decided to join the recently formed Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Annie became involved immediately and began regularly visiting the Pankhursts' Manchester home, and with their encouragement she stood for election to the textile union committee, became its first woman member, and began (but did not complete) a correspondence course at Ruskin College. (12)

Jessie was not initially swept up by the fervour as her sister Annie and continued living with her father and sister Alice. On 13th October 1905, Annie and Christabel Pankhurst attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were both arrested. (13)

Christabel Pankhurst was charged with assaulting the police and Annie Kenney with obstruction. In a deliberately aggressive courtroom speech, Christabel admitted that she has assaulted police officers and pointed out that "I am only sorry that one of them was not Sir Edward Grey... We cannot make any orderly protest because we have not the means whereby citizens may do such a thing: we have not a vote, and so long as we have not a vote we must be disorderly... When we have that, this will not see us in the police courts; but so long as we have not votes this will happen." (14)

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were both found guilty. Pankhurst was fined ten shillings or a jail sentence of one week. Kenney was fined five shillings, with an alternative of three days in prison. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. (15)

Emmeline Pankhurst was very pleased with the publicity achieved by the two women. "The comments of the press were almost unanimously bitter. Ignoring the perfectly well-established fact that men in every political meeting ask questions and demand answers of the speakers, the newspapers treated the action of the two girls as something quite unprecedented and outrageous... Newspapers which had heretofore ignored the whole subject now hinted that while they had formerly been in favour of women's suffrage, they could no longer countenance it." (16)

In 1906 Jessie Kenney was invited by Annie Kenney to become secretary to the WSPU treasurer, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. (17) She quickly gained a reputation for her capability and was appointed the WSPU's youngest organizer. According to her biographer, Lyndsey Jenkins: "Jessie Kenney was a hands-on worker, ready to turn her skills to anything that needed to be done." (18)

Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "By the time she was 21 she was the Women's Social and Political Union's youngest organizer, working from Clement's Inn, arranging meetings, publicity stunts, interruptions of cabinet ministers' meetings and, as time passed, acts of militancy." (19)

For a time, Jessie took on the role of prisoners' secretary, liaising between imprisoned suffragettes and their families. Working with Christabel Pankhurst, Jessie Kenney was central to organizing the pageants and processions that shaped the suffragettes' image. Annie wrote that "Christabel insisted on Jessie's room being next to hers, as she looked upon her as absolutely indispensable for the carrying out of her London plans" (20)

On 30th June 1908 Jessie was arrested during a demonstration in Parliament Square and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment. Her release was reported in Votes for Women. "On Friday morning the first batch of prisoners to be released from Holloway were met at the prison gates, and escorted in triumph, banners flying and bands playing, to Queen's Hall, where some 250 friends and supporters were waiting to give then a warm welcome." Kenney was quoted as saying: "At first, they were very strict; the prisoners were in their cells from 11.30 am to 8.30 next morning, with the exception of fetching water, etc. The second week, however, things were different. The wardresses were kinder, and there were many visits from doctors, magistrates, chief matrons, and others. Then two exercise times were instituted, and associated work. The chief cause of discontent was the lack of ventilation – the cells were shifting. Some of the women sprinkled the floor with water, thereby lessening their water supply." (21)

Mary Blathwayt

Jessie Kenney and Annie Kenney were regular visitor to the home of Colonel Linley Blathwayt. His wife, Emily Blathwayt, and his daughter, Mary Blathwayt, held progressive political views and were both advocates of women's suffrage. Colonel Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and Eagle House, on the outskirts of Bath, that was called the "Suffragette Rest". Colonel Blathwayt photographed the WSPU visitors. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars. Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay with the family. Colonel Blathwayt also designed an arboretum which was planted with trees by suffragette ex-prisoners. Eventually, fifty-four trees with their accompanying placq were established there. (22)

planting a tree at "Suffragette Rest" at Eagle House in 1909.

Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU at Batheaston. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote in her diary that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." (23) Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account. (24)

The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else." (25)

Colonel Linley Blathwayt and Emily Blathwayt opened their home to members of the WSPU. They came to stay for rest and recuperation after prison, including hunger-strikers. The Blathwayts were the first people in their village to own a motor car which they loaned to the WSPU. Colonel Blathwayt also owned a camera and took photographs of several women including Jessie Kenney. (26)

Attacks on Herbert Asquith

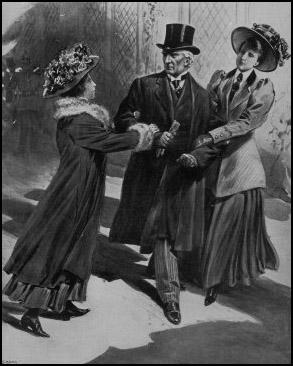

A team of suffragettes led by Jessie Kenney and including Vera Wentworth, Mary Phillips and Elsie Howey, decided to target the prime minister, Herbert Asquith. There first incident took place in August 1909. Howey said in court: "We wish to say we don't think we are the guilty parties. We did obstruct the police, but we were only performing our duty. The Liberal Government is directly responsible for this. We have tried again and again to get Mr Asquith to see a deputation and explain what we want, but he will not see our deputations. Therefore, we must go to work differently. We have warned him that other things may happen if he will not listen to us. If we do not worse things it is not because we are afraid, but because we do not want to hurt anyone." (27)

The level of violence used by the women shocked Mary Blathwayt. She wrote in her diary: "We hear of terrible things by the two Hooligans we know, Vera and Elsie and there is a Kenney in it. They made a regular raid on Mr. Asquith breaking a window and using personal violence. Then missiles have been thrown lately through windows during Cabinet Members meetings which might injure or kill innocent persons." (28)

The following month they decided to visit Asquith when he was spending the weekend with Herbert Gladstone, his home secretary, at Lympne Castle. Kenney wrote about this in Votes for Women: "Vera Wentworth, Elsie Howey an I arranged our plans accordingly, and we decided to go down, too, and remind Mr. Asquith... that he would not have much peace until he did his duty to the women of the country. On Sunday morning we disguised ourselves ready for the occasion. Miss Vera Wentworth disguise as a nurse being especially successful. We took a boat up the Military Canal, which runs just below the Castle grounds, and moored it almost facing the Castle."

It was decided to accost Asquith when he went to church on Sunday morning. "We then went up to the churchyard, whence we could command a good view of both of the Castle gates and the entrance of the church. We had not been there very long when we saw Mr Asquith making his way into church, so we waited until the service was over. As he was going from the church to the little door which led to the Castle we hastened up towards him, and he began to run. He was just slipping through the door when we caught him. He got wedged in the door, and a struggle ensued, in which his hat was knocked off. He tried to recover both his hat and his dignity, but looked extremely afraid. Mr Asquith, I think, quite understood the position as we had warned him at Clovelly that the women were not going to tolerate his attitude to them much longer. It was a real "Deeds not words" affair. Not a word was spoken on either side. Mr Asquith managed to squeeze through by the aid of someone who came to his help, and the door was shut." (29)

Herbert Asquith later recalled: "The contest was very evenly balanced... The women outside obviously meant business; they succeeded in prising the doors a short distance apart and while he stood spread-eagled in front of them with a hand on each door, one of them inserted herself in the crevice between and began butting him in the diaphragm with her head." Herbert Asquith junior got hold of her wrist and she fought with "a strange demonic frenzy which I had never met and hope never to see again." (30)

That afternoon they decided to attack Asquith when he played golf with Gladstone at Littlestone-on-Sea. "We saw him quietly descending the steps, and making his way down the footpath to the motor- Miss Howey then made a dash up the path, and as soon as he saw her coming, he turned round and ran back again, and was almost on the top step when she caught him. He then said to Miss Howey, 'I shall have you locked up,' but she promptly returned, 'I don't care what you do, Mr. Asquith!' Vera Wentworth, and I then followed, and his hat was thrown off again in the scrimmage. When we arrived on the scene, Mr. Asquith was calling for help and trying to push Miss Howey out of the porch. At the call of Mr. Asquith, Mr. Gladstone came on the scene, and a real fight ensued. Mr. Gladstone and Mr. Asquith tried to push us down the steps, but we pushed back as hard as they pushed forward. Mr Gladstone fought like a prize fighter, and struck out left and right. I must say he is a better fighter than he is a politician!" (31)

Emily Blathwayt commented in response from a letter from Vera Wentworth: "Long letter from Vera Wentworth who is very sorry we are grieved but if Mr. Asquith will not receive deputation they will pummel him again. She says the authorities knew nothing of the raid for which they alone are responsible. They are driven nearly mad by the unjust treatment all their dear women have received and she points out they did no serious harm to Asquith whereas Herbert Gladstone gave Jessie a nasty blow in the chest. She also says what the liberal stewards have done at the meetings to the women. She really believes she is acting quite rightly." (32)

The women were arrested and appeared in court accused of assaulting Asquith and Gladstone. (33) Emily Blathwayt sent a letter to the WSPU headquarters: "Dear Madam, with great reluctance I am writing to ask that my name may be taken off the list as a Member of the W.S.P.U. Society. When I signed the membership paper, I thoroughly approved of the methods then used. Since then there has been personal violence and stone throwing which might injure innocent people. When asked by acquaintances what I think of these things I am unable to say that I approve, and people of my village who have hitherto been full of admiration for the Suffragettes are now feeling very differently." (34)

On their release were met at the gates of Holloway Prison and then drawn by 50 women on a carriage to Queen's Hall. On their arrival they were presented with bouquets in the suffragette colours and with illuminated scrolls designed by Sylvia Pankhurst to commemorate their imprisonment. Jessie's importance to the organization also meant that the leadership preferred to keep her out of prison. In her unpublished autobiography she comments that "I had to be shielded as Christabel wanted me to be kept as a dark horse". (35) This experience damaged her health and in 1910 she was taken on holiday to Switzerland by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. (36)

In October 1910 she was WSPU organiser at the Walthamstow by-election. She did the same job at the South Hackney by-election. According to Mary Blathwayt Jessie Kenny developed a "lung condition" and was sent abroad to recuperate in 1913. The following year she went to live with Christabel Pankhurst in Paris. However, between May and August she travelled every week to Glasgow, under the name, Mary Fordyce, in order to see The Suffragette through the press in the cellar where it was printed. (37)

In May 1912, Horatio Bottomley, the Liberal MP for Hackney South, was forced resign his seat when he was declared bankrupt. Jessie Kenney was placed in charge of the WSPU campaign in the by-election. Angry with the Liberal government for not granting women the vote, the WSPU supported the Conservative Party candidate against Hector Morison. The WSPU claimed that its campaign was responsible for Morison's reduced majority: "The magnificent result in reducing to 500 a Liberal majority of nearly 2,000 is one which Suffragettes will have hailed with gladness and the Government with consternation. The Government was indeed alive to its own probable failure in fixing the polling day at such an early date, and it can be confidently asserted that with another week's efforts the result would have been more striking still under the direction of Miss Jessie Kenney an extensive campaign was organised. Outdoor meetings were held each night, and it was delightful to notice the celerity with which men and women alike left Liberal and Conservative meetings to give ear to the Suffragettes. The women were splendid, especially to the poorer parts." (38)

Conspiracy Trial

On 30th April 1913 the police raided the WSPU's office at Lincoln's Inn House. As a result of the documents found several people were arrested including Edwy Godwin Clayton, Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney, Rachel Barrett (editor of the The Suffragette), Harriet Kerr (office manager), Beatrice Sanders (financial secretary), Geraldine Lennox (sub-editor) and Agnes Lake (business manager). (39)

When he was arrested Clayton said: "I think this is rather a high-handed action. I am an extreme sympathizer with the Suffragette causes. What evidence have you against me?" He confirmed he had written the letter but refused to comment on the contents. The letter read: "Dear Miss Kenney, I am sorry to say it will be several days yet before I can be ready with which you want. I have devoted all this evening and all of yesterday evening to the business without success. Evidently it is a difficult matter, but not impossible. I nearly succeeded once last night and then spoilt what I had done in trying to improve upon it. By next week I shall be able to manage the exact proportions, and I will let you have the results as soon as I can. Please burn this." (40)

During the trial Matthias McDonnell Bodkin read extracts from a document headed "Votes for Women" and underneath "YHB". Bodkin claimed that YHB stood for Young Hot Bloods. The label was derived from a taunt thrown at Emmeline Pankhurst in one of the newspapers, which ran: "Mrs Pankhurst will, of course, be followed blindly by a number of the younger and more hot-blooded members of the union". (41) As a result of them being single women one newspaper described the Young Hot Bloods as "a spinsters' secret sect". (42)

Bodkin claimed that the police seized a great number of documents, that showed according to Bodkin that Clayton "put his knowledge and his brain at the Union's disposal for the purpose of carrying out crimes and of producing the reign of terror in London." Receipts for money he had been paid by the union were produced in court. (43)

The most incriminating evidence was a letter sent by Clayton to Jessie Kenney in April 1913 that was found inside a book on the 1831 Bristol Reform Riots. Bodkin said: "We did not know until these documents were seized at their offices that they had an analytical chemist in their service – a man who, as we know, written a secret letter which the vain folly of Miss Kenney causes her to leave in her bedroom. the letter he tells her he had been experimenting, and was on the brink of success. Clayton ended his letter: "Burn this letter." (44)

Bodkin provided other documents written by Clayton. One document in Clayton's writing was headed "Various Suggestions" and read "Scheme of simultaneously smashing a considerable number of street fire-alarms. This will cause tremendous confusion and excitement and should be as especially a good idea. It should be at once easier and less risky to execute than some other operations". Particulars as to timber yards and cotton mills also followed, as well as a plan for burning down the National Health Insurance Office. (45)

Another witness Mrs Strange, the proprietress of the refreshment pavilion at Kew Gardens, estimated the amount of damage done to the pavilion by the fire which took place there some time ago. Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry were arrested and when they appeared at Richmond Police Court, she saw Clayton with them. (46)

In his summing up Justice Walter Phillimore, remarked that it was one of the saddest trials in his experience of nearly sixteen years as a Judge. "How in morals and how in good practical sense could such things, if they be true be justified? It was said that great causes had never been won without breaking the law. That might be true of some cases; it was very untrue of others. If every recorded act of anarchy, then, as history proceeded on its long course, the human race would reach a position of absolute savagery, and the only chance of salvation would be the obliteration of memory." (47)

During the trial, Rachel Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone." (48) Barrett was sentenced to six months in prison. She was described by one of the prosecuting barristers at the trial as "a pretty but misguided young woman". (49)

After an absence of an hour the jury found all the prisoners guilty, with strong recommendations for leniency of sentence in the case of the three younger women, Rachel Barrett, Geraldine Lennox and Agnes Lake. The Judge said: "I agree with you, gentlemen of the jury, in the discrimination which you have made between the younger and elder men and women… which I propose to show in their sentences: As I have said, I assume you have been animated through out by the best motives. It is not merely that some of you have committed organized outrages, but I am more concerned with the incitement that has been given to young and irresponsible women, whose actions are not always balanced by their reason to do things which you are sure to regret." (50)

Annie Kenney was sentenced to eighteen months but it was Edwy Godwin Clayton who was treated most harshly and got twenty-one months. He went on hunger strike and was released on license, however, he went on the run and managed to evade arrest and went to live in Europe. (51)

First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (52)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote an article in The Suffragette where she argued: "A man-made civilisation, hideous and cruel enough in time of peace, is to be destroyed... This great war is nature's vengeance - is God's vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection... that which has made men for generations past sacrifice women and the race to their lusts, is now making them fly at each other's throats and bring ruin upon the world... Women may well stand aghast at the ruin by which the civilisation of the white races in the Eastern Hemisphere is confronted. This then, is the climax that the male system of diplomacy and government has reached." (53)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Emmeline Pankhurst said that militancy would be pointless in the face of the infinitely greater violence of war. "What will come out of this European war - so terrible in its effects on the women who had no voice in averting it - so baneful in the suffering it must necessarily bring on innocent children - no human being can calculate. But one thing is reasonably certain, and that is that the Cabinet changes which will necessarily result from warfare will make future militancy on the part of women unnecessary. no future Government will repeat the mistakes and the brutality of the Asquith Ministry." (54)

Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (55) In another interview she stated: "We suffragists... do not feel that Great Britain is in any sense decadent. On the contrary, we are tremendously conscious of strength and freshness." (56)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (57)

Jessie Kenney remained a highly trusted confidante and ally of the Pankhursts during the war. In 1915 she accompanied Emmeline Pankhurst to Russia where the two women attempted to persuade leading politicians to support the allied cause. They had a meeting with Alexander Kerensky, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR), but he seemed to resent their presence. The women got a much better response from Maria Bochkareva, the leader of the Women's Battalion. (58)

On her return to England both women gave lectures on Russia and the First World War. After the Russian Revolution Kenney gave a talk on "Conditions and Prospects in Russia and the Lesson of the Russian Situation to the British People" at Queen's Hall, Langham Place, London. (59).

The Qualification of Women Act

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. MPs rejected the idea of granting the vote to women on the same terms as men. Lilian Lenton, who had played an important role in the militant campaign later recalled: "Personally, I didn't vote for a long time, because I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30." (60)

The Qualification of Women Act was passed in February, 1918. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The Representation of the People Bill, which doubles the electorate, giving the Parliamentary vote to about six million women and placing soldiers and sailors over 19 on the register (with a proxy vote for those on service abroad), simplifies the registration system, greatly reduces the cost of elections, and provides that they shall all take place on one day, and by a redistribution of seats tends to give a vote the same value everywhere, passed both Houses yesterday and received the Royal assent." (61)

Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst now dissolved the Women's Social & Political Union and formed The Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (i) A fight to the finish with Germany. (ii) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (iii) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." (62)

Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions. David Lloyd George commented to Andrew Bonar Law, that the Women's Party had been very useful in the fight against the Labour Party: "The Women's Party... has been extremely useful, as you know, to the Government especially in the industrial districts where there has been trouble during the last two years. They have fought the Bolshevik and Pacifist element with great skill, tenacity and courage." (63)

Jessie Kenney was one of the leading figures in the party. The Britannia reported. "On Sunday, January 27, a successful meeting was held at the Woolwich Hippodrome. Miss Jessie Kenney on taking the chair, explained the absence of Miss Christabel, who was to have addressed the meeting. Miss Kenney gave a short account of the aims and ambitions of the Women's Party, outlining the party programme and policy, and appealing to the newly enfranchised members of the audience to join. She then called upon Mrs Drummond, who, in an excellent speech, made reference to a former visit to Woolwich during the hard struggle for woman's enfranchisement. Since then the old WSPU had become the Women's Party." (64)

Christabel Pankhurst became one of the seventeen women candidates that stood in the 1918 General Election. She represented the Women's Party in Smethwick, and the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down so it could be a straight fight with the Labour Party. Both Jessie and Annie Kenney worked on the campaign. (65) Christabel accused the Labour candidate, John E. Davidson, of being a Bolshevik. Davidson replied that far from being "corrupted and led by Bolshevists' the Labour Party stood for social reform along constitutional lines "without breaking a single window, firing a single pillar-box, or burning down a single church." Davidson beat Pankhurst by 775 votes. (66)

Later Life

After the war Jessie Kenney worked for the American Red Cross in Paris. She became the first woman to qualify as a ship's Radio Officer (1st Class certificate in wireless operating) but, being a woman, was not allowed to practise. Instead, she worked as a steward on cruise liners. In between her trips she lived with Annie Kenney at her home in Letchworth. (67)

Jessie later found more fulfilling work as a school administrator in London. She kept her membership of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) a secret as she believed it would cause her problems in her career. In the 1950s she began an autobiography, The Flame and the Flood in an attempt to correct what she saw as the inaccuracies that had arisen around the suffragette movement and particularly her sister's role in it. She was deeply upset at the way that her sister Annie Kenney came to be portrayed within both historical writing and popular culture, blaming Sylvia Pankhurst "for creating a caricature of an ignorant and uncritical devotee who simply did what she was told." Jessie also felt guilt over not destroying the letter from Edwy Godwin Clayton that resulted in her sister Annie Kenney being sent to prison for eighteen months (68)

Jessie Kenney, who converted to Catholicism, and lived in a retirement home run by nuns, died in Braintree on 6th November 1985.

Primary Sources

(1) Votes for Women (18th June 1908)

Miss Jessie Kenney is one of the many young speakers and writers developed by the needs of the women's movement. She was born in 1887 at Lees, near Oldham, and at 13 went to work in a cotton factory, meanwhile attending evening classes at night schools and devoting her spare time to the village Sunday School. At 19 she came to London, and has been private secretary to Mrs Pethick Lawrence ever since.

(2) Votes for Women (6th August 1908)

On Friday morning the first batch of prisoners to be released from Holloway were met at the prison gates, and escorted in triumph, banners flying and bands playing, to Queen's Hall, where some 250 friends and supporters were waiting to give then a warm welcome….

Miss Jessie Kenney said she had not yet got used to being allowed to talk without hearing from somewhere in the background, "Hold your tongue, No. 2!" Indeed, she seemed still to hear it. Her experience of Holloway was that it was a very nice place to live out of. Her impressions was that the authorities did not know how to treat the Suffragettes.

At first, they were very strict; the prisoners were in their cells from 11.30 am to 8.30 next morning, with the exception of fetching water, etc. The second week, however, things were different. The wardresses were kinder, and there were many visits from doctors, magistrates, chief matrons, and others. Then two exercise times were instituted, and associated work. The chief cause of discontent was the lack of ventilation – the cells were shifting. Some of the women sprinkled the floor with water, thereby lessening their water supply.

(3) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (9th May, 1909)

Mary planted her golden holly near Annie's but in the outer circle, and Jessie Kenney having been to prison planted near Annie's in the inner. Vera Holme also put a tree below Mary's. She is a splendid woman and interested in all Linley's subjects and she took up Mary's violin and was very clever with it. She has a beautiful voice and we sang after washing up. Suffragettes are splendid for any work.

(4) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (31st July, 1909)

Elsie Howey, Vera Wentworth and Mary Phillips were arrested at Exeter and imprisoned for a week and it is said they are going through the hunger strike as the 14 have done. The crowds were with them outside Lord Carrington's meeting and all resisted police and two working men were arrested. The women would not pay the fine. Annie Kenney expects to be taken soon herself, and asked Mary to go and manage for her in Bristol.

(5) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (4th September, 1909)

We drove down to Bristol station, and formed up into a procession; it was to receive Mrs. Dove Willcox and Miss Mary Allen, two ex-prisoners and hunger strikers on their return to Bristol. A military band had promised to play, but they declined at the last moment. First came a carriage containing Mrs. Dove Willcox, and Miss Mary Allen; Annie Kenney and some others walked just behind it and then followed a long procession of ladies with banners and tricolour. I helped to carry a banner marked Finland. A very long line of carriages followed. The roads were muddy and it rained a little at first.

(6) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (7th September, 1909)

Linley and I went in pouring rain to the Tollemaches who had a tent beyond their house and Mr. Laurence Housman gave a very good address on Women's Suffrage... The lecturer said he could not say anything against militant methods as the women had been driven to it by the non-action of the men. I cannot feel quite the same. We hear of terrible things by the two Hooligans we know, Vera and Elsie and there is a Kenney in it. They made a regular raid on Mr. Asquith breaking a window and using personal violence. Then missiles have been thrown lately through windows during Cabinet Members meetings which might injure or kill innocent persons.

(7) Jessie Kenney, Votes for Women (10th September 1909)

Having ascertained that Mr Asquith would be going to Lympne, this weekend, Vera Wentworth, Elsie Howey an I arranged our plans accordingly, and we decided to go down, too, and remind Mr. Asquith, as we did at Covelly (only more forcibly), that he would not have much peace until he did his duty to the women of the country.

On Sunday morning we disguised ourselves ready for the occasion. Miss Vera Wentworth disguise as a nurse being especially successful. We took a boat up the Military Canal, which runs just below the Castle grounds, and moored it almost facing the Castle…

We then went up to the churchyard, whence we could command a good view of both of the Castle gates and the entrance of the church. We had not been there very long when we saw Mr Asquith making his way into church, so we waited until the service was over. As he was going from the church to the little door which led to the Castle we hastened up towards him, and he began to run. He was just slipping through the door when we caught him. He got wedged in the door, and a struggle ensued, in which his hat was knocked off. He tried to recover both his hat and his dignity, but looked extremely afraid. Mr Asquith, I think, quite understood the position as we had warned him at Clovelly that the women were not going to tolerate his attitude to them much longer. It was a real "Deeds not words" affair. Not a word was spoken on either side. Mr Asquith managed to squeeze through by the aid of someone who came to his help, and the door was shut…

That was only the beginning of our campaign. We made our plans all ready for the afternoon and we decided that we would try and catch Mr. Asquith and Mr. Gladstone together at Littlestone-on-Sea, a small seaside village some miles from Lympne, as we ha a good idea that they would golf together that afternoon.

Soon we saw him quietly descending the steps, and making his way down the footpath to the motor- Miss Howey then made a dash up the path, and as soon as he saw her coming, he turned round and ran back again, and was almost on the top step when she caught him. He then said to Miss Howey, "I shall have you locked up," but she promptly returned, "I don't care what you do, Mr. Asquith!" Vera Wentworth, and I then followed, and his hat was thrown off again in the scrimmage. When we arrived on the scene, Mr. Asquith was calling for help and trying to push Miss Howey out of the porch. At the call of Mr. Asquith, Mr. Gladstone came on the scene, and a real fight ensued. Mr. Gladstone and Mr. Asquith tried to push us down the steps, but we pushed back as hard as they pushed forward. Mr Gladstone fought like a prize fighter, and struck out left and right. I must say he is a better fighter than he is a politician!

(8) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (16th September, 1909)

Long letter from Vera Wentworth who is very sorry we are grieved but if Mr. Asquith will not receive deputation they will pummel him again. She says the authorities knew nothing of the raid for which they alone are responsible. They are driven nearly mad by the unjust treatment all their dear women have received and she points out they did no serious harm to Asquith whereas Herbert Gladstone gave Jessie a nasty blow in the chest. She also says what the liberal stewards have done at the meetings to the women. She really believes she is acting quite rightly. The letter needs no reply.

(9) Dundee Evening Telegraph (23rd November, 1910)

Scenes of violence unparalleled in the history of the women's suffrage movement took place in Downing Street, Westminster. For over a quarter of an hour some 300 women members of the Women's Social and Political Union fought fiercely and with the utmost determination in the endeavour to break through the cordon of police which had been hastily drawn up at the entrance to the street in order to guard No 10, the residence of the Prime Minister, which was the objective of the women ...

Exactly 100 arrests were made, including some of the leaders of the suffrage movement. Later, following on a second concerted attempt to get to Mr. Asquith's house, several more arrests were made... The following is a list of the Suffragettes arrested: Emmeline Pankhurst, Catherine Marshall, Evaline Haverfield, Maude Sennett, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Bertha Brewster, Kitty Marion, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Lilian Dove-Wilcox and Grace Roe.

(10) Votes for Women (31st May 1912)

The magnificent result in reducing to 500 a Liberal majority of nearly 2,000 is one which Suffragettes will have hailed with gladness and the Government with consternation. The Government was indeed alive to its own probable failure in fixing the polling day at such an early date, and it can be confidently asserted that with another week's efforts the result would have been more striking still under the direction of Miss Jessie Kenney an extensive campaign was organised. Outdoor meetings were held each night, and it was delightful to notice the celerity with which men and women alike left Liberal and Conservative meetings to give ear to the Suffragettes. The women were splendid, especially to the poorer parts.

(11) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (19th July, 1915)

The women under the W.S.P.U. management had a wonderful procession in London on Saturday, and the papers which used to be abusive are now praising them highly. Mrs. Pankhurst was head and chief and Annie was one of the prominent ones... They are demanding war work and Lloyd George who received them graciously is only too glad to have them now.

(12) The Britannia (1st February 1918)

On Sunday, January 27, a successful meeting was held at the Woolwich Hippodrome. Miss Jessie Kenney on taking the chair, explained the absence of Miss Christabel, who was to have addressed the meeting.

Miss Kenney gave a short account of the aims and ambitions of the Women's Party, outlining the party programme and policy, and appealing to the newly enfranchised members of the audience to join. She then called upon Mrs Drummond, who, in an excellent speech, made reference to a former visit to Woolwich during the hard struggle for woman's enfranchisement. Since then the old WSPU had become the Women's Party.

(13) David Simkin, Family History Research (16th September, 2022)

Jessie Kenney was born on 1st April 1887 at Springhead, Saddleworth, in the West Riding of Yorkshire . the ninth of twelve children (Clara, the last born died in infancy). Her parents were Horatio Nelson Kenney and Ann Wood. Her father was a spinning machine minder in a cotton mill (at the time of Jessie's birth, he described himself as a "Self Actor Minder" - a man who looked after a 'Self Acting Mule' - the name of a multi-thread spinning machine). In 1891, Horatio N. Kenney described himself as a "Cotton Spinner or Minder " but surprisingly, in the 1901 Census 51-year-old Horatio N. Kenney declared he was "Living on Own Means". On the 1901 Census return is recorded as a 14-year-old cotton mill worker, as were all the sisters who were still living at home in Springhead, Saddleworth ,