Gladice Keevil

Gladice Keevil, he youngest of six children born to Georgina Mary Moon (1852–1947) and William Richard Keevil (1853–1929), was born in 1884. Her father was a "Farmer & Dairyman" of Clutterhouse Farm, Cricklewood, Middlesex. At the time of the 1891 Census, the family had a female domestic servant living at the farm. (1)

After being educated at the Frances Mary Buss School in Camden and at Lambeth Art School she worked as a governess for 18 months in France and the United States. On her return to England in 1907 she joined the Women's Social and Political Union. (2)

Keevil worked closely with Emma Sproson who was a member of the Wolverhampton Independent Labour Party. (3) In April 1907 the two women arranged for Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence to join them in a series of Market place meetings. (4) Keevil also recruited Hilda Burkitt as a paid organiser in Birmingham. "Hilda held regular evening meetings in parks and on street corners to bring the movement to attention of residents on their way home from work." (5)

In February 1908 she was one of those arrested with Emmeline Pankhurst in taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons. Keevil was found guilty and spent six weeks in Holloway Prison. (6) On her release she was appointed National Organiser in the Midlands and established a regional office in Birmingham. Later she was joined by Ada Flatman. (7)

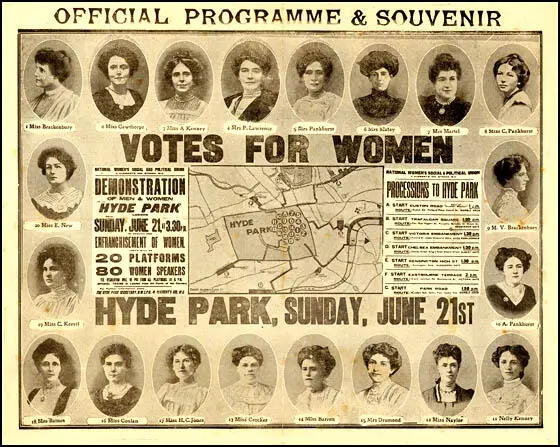

Gladice Keevil also spoke at Hyde Park meeting on 21st June 1908. The Daily News reported that: "Miss Keevil was a particularly striking figure. Robed in flowing white muslin, her lithe figure swayed to every changing expression, and the animated face that smiled and scolded by turns beneath the black straw hat and waving white ostrich feather, was the centre of one of the densest crowds." (8)

Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of the estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest". Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay at Eagle House and the summer-house. Colonel Blathwayt decided to create a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. The idea was for women to be invited to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes. (9)

Mary Blathwayt recorded Gladice Keevil's visit in May 1908. "Miss Keevil came over from Market Drayton ... She and I held an open air meeting at the Wharf. I took the chair, the first time I have ever done such a thing. I read out a few words of introduction, announced a meeting for tomorrow and called upon Miss Keevil to speak." (10)

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Gawthorpe, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New. (10a)

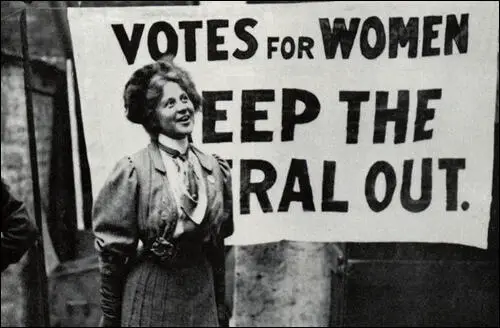

Gladice Keevil became a popular speaker at WSPU meetings all over the country. B. M. Willmott Dobbie pointed out that she was "noted for her good looks." (11) This included a meeting in Leeds on 26th July 1908, which included speeches from Emmeline Pankhurst, Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jennie Baines, Adela Pankhurst, and Flora Drummond. The local newspaper reported: "Miss Gladys Keevil, a young lady with a winning smile and a most becoming hat, exerted a distinct influence upon her hearers. She admitted that some of the doings of the Suffragettes had not been quite lady-like, but she pleaded that they had done nothing unwomanly." (12)

On 22nd September 1909 Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth, Mabel Capper, Patricia Woodcock, Hilda Burkitt and Rona Robinson conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work." (13)

The Freeman's Journal reported: "Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand. Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck. A policeman who climbed on the roof - a hazardous undertaking - found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: 'Come on up at your peril,' the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest." (14)

At a meeting in Birmingham that evening Gladice Keevil pointed out that the WSPU felt "very grateful to the few men who were courageous enough to protest where Mr Asquith was speaking on the Budget". However, it was vitally important that women influenced government policy: "What was wanted was the women's point of view. It was the housekeeping women who know how to make a pound go as far as a man would take 25s so really the Budget was a great argument in their favour." She added "that the Suffragists were determined that... women were going to take their share of the work of building up the nation." (15)

Hilda Burkitt like the other women arrested at the rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the women by force. (16)

On the 20th September, 1909, Hilda declared in an official petition to the Home Office that until her political status was acknowledged, she would "refuse to take any Prison Food, & as far as is in my power I shall break all prison rules". She demanded that the Home Office "reply to my Petition at once, as if I should die through my fasting, my death will lie at your door." Hilda pointed out that she was "ready to lay down my life, to bring about the Freedom of my Sex." (17)

Hilda refused to eat any food. "Hilda was examined in the morning by the prison doctor and one sent especially by the Home Office. That afternoon, she was taken to the prison kitchen, where four wardresses, a matron and two doctors attempted and eventually succeeded in restraining her to a chair with a blanket. Hilda shouted 'I will not take food! I refuse! I will not swallow!' and continued to resist attempts to feed her from a cup. In response, the prison doctor declared that ‘illegal or not, I'm going to use it' and proceeded to attempt feeding by nasal tube. Hilda continued to resist and coughed the tube out twice.... The doctors then gagged her and used a stomach tube to feed her through her mouth. Afterwards, Hilda repeated what she had said to the wardresses - 'I'm broken, but not beaten'. These experiences were repeated throughout her month in Winson Green as she undertook three hunger strikes, lasting 86, 91 and 24 hours respectively. Suffering great pain, she only managed sleep for four nights out of the entire month." (18)

Gladice Keevil visited Hilda Burkitt in prison and the Nursing Home where she was taken after her release. She also complained about the way Mary Leigh had been treated in prison: "Miss Keevil also spoke on Friday at the weekly meeting in the Bull Ring, when, in spite of threatening weather, there was a good crowd, and many more questions were asked. Great indignation is felt at the continued imprisonment of Mrs Leigh while other women of more influential position have been released." (19)

In July 1910, Gladice Keevil addressed several meetings in Northern Ireland. This included one speech at the Ulster Minor Hall: "Miss Keevil, who was cordially welcomed explained that they (WSPU) made their claim for the vote not on the grounds of sentiment but on the ground of simple justice. Women were considered adult enough to pay taxes, but not to vote." (20) One member of the audience commented that she was a "clever speaker and knows her subject". (21)

Keevil was a regular visitor to Eagle House near Batheaston. Her host, Emily Blathwayt, described her as "a very nice girl... she seems interested in all subjects and enjoyed everything here... one of the nicer Suffragettes". On 4th November 1910 Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Picea Pungens Kosteriana, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. (22)

Gladice Keevil was still active in the WSPU on 28th November, 1912. (23) This came to an end when she married Leslie Rickford, a 25-year-old bank clerk. She gave birth to three children: Lionel (born 1st June, 1914, Barnet, Middlesex - died 23rd May,1997, Worthing, West Sussex), Richard (born 1st June, 1914, Barnet, Middlesex – died 16th March,1990, Dartmouth, Devon) and Cecil (born 1917, Barnet, Hertfordshire - died 8th July 1964 at Warne House, Burpham, near Arundel, West Sussex).

After their marriage the family lived at 180 Willifield Way, Hendon. Between 1925 and 1946 Gladice Rickford made several journeys to India and Pakistan. It appears that by the 1920s, Gladice's husband, Leslie Rickford was a banker based in Bombay, India. After the Second World War he was a bank manager in England and the couple lived at 10 Houndean Rise, Lewes, Sussex.

After her husband's death in 1956 Gladice Rickford moved to the Wall Cottage, Burpham, near Arundel, West Sussex. She died on 5th November 1959, aged 75, at St Thomas Hospital, Lambeth, London. She left effects valued at £19,970. 6s 7d. (24)

Primary Sources

(1) Mary Blathwayt, diary entry (11th May, 1908)

Miss Keevil came over from Market Drayton ... She and I held an open air meeting at the Wharf. I took the chair, the first time I have ever done such a thing. I read out a few words of introduction, announced a meeting for tomorrow and called upon Miss Keevil to speak.

(2) The Leeds Mercury (27th July, 1908)

There was a great gathering on Woodhouse Moor yesterday afternoon, when the Suffragettes held a demonstration. how many assembled one must not be betrayed into venturing to estimate, and so it may be left as many thousands. The weather was favourable, and the public prepared to make the best of it.

A procession was formed and proceeded to the Moor, headed by bands playing stirring airs. On the Moor were arranged ten conveyances by way of platforms, and from these prominent members of the cause held forth more or less strenuously.

The speakers included such well-known adherents as Mrs Pankhurst, Miss Annie Kenney, Miss Mary Gawthorpe, Mrs Pethick Lawrence, Miss Gladys Keevil, Mrs Baines, Miss Adela Pankhurst, and Mrs Drummond. The crowd was undoubtedly swelled by many who went out of curiosity and a desire to see if there were any disturbance. A band performance was in progress also, and on the skirts of the demonstration the Salvation Army and others made the most of the opportunity by holding meetings.

There was no serious disturbance. Here and there one or two noisy spirits elbowed their way into the crowd and ventured upon an occasional interruption. In one instance, too, a man proceeded from reviling the Suffragettes to reviling women in general, with the result that he was made to beat a speedy retreat by means of chaff, mingled with the more substantial persuasion of sods.

Miss Gladys Keevil, a young lady with a winning smile and a most becoming hat, exerted a distinct influence upon her hearers. She admitted that some of the doings of the Suffragettes had not been quite lady-like, but she pleaded that they had done nothing unwomanly.

There were some things that only women could do. Men, she said, were actually debating in the House of Commons as to whether a mother should have her young child with her in bed or in a cot by her side.

"Why," she said, with a smile, "the stupidest woman knows more about children and their training than the wisest of men."

They did not want the Liberal party to be deprived of power, because they looked to the Liberals to give them the vote. What they were doing was to shake the party, just as a mother might shake a naughty child.

Mrs Pankhurst was as clever as usual in dealing with questions. The adult suffragist meets with scant consideration at her hands. One such was told that if he was sincere he would not use his vote until his wife got one. They were not going to wait until everybody could have the vote. Man wanted woman to pull some more chestnuts out of the fire for him.

As for a programme, said Mrs Pankhurst, they were political dark horses, and they were not going to declare any political programme until they could vote on one.

"Are there not more women than men?" asked a fearful male, trembling as before the wrath to come.

"There are more men born than women," said Mrs Pankhurst, triumphantly, "but fewer survive. It seems to me you men want mothering." And the abashed man looked as if he did.

A resolution advocating "Voted for Women" was put, and carried by a huge majority. At Mrs Pankhurst's platform, for instance, there were but three hands, and one stick with a hat upon it, held up in opposition.

(3) Birmingham Daily Gazette (23rd September 1909)

At the Priory Rooms, Birmingham, last evening, Miss Gladice Keevil presided over a largely attended meeting organised by the National Women's Social and Political Union.

Miss Keevil said as they watched the unparalled precautions that were taken by the police to prevent Mr Asquith seeing or hearing Suffragists, they put their tongues out; but reading between the lines of a report which had appeared in the London Press, it appeared that the party had not gone as far as expected. It seemed to be a common opinion that they intended throwing bombs or firing the tarpaulin which was spread over Bingley Hall to prevent the Suffragists from getting their messages through the roof…

The party felt very grateful to the few men who were courageous enough to protest on their behalf when they were inside the hall, where Mr Asquith was speaking on the Budget. What was wanted was the women's point of view. It was the housekeeping women who know how to make a pound go as far as a man would take 25s so really the Budget was a great argument in their favour. Miss Keevil went on to say that the Suffragists were determined that, whoever was speaking as Mr. Asquith spoke, there would be some protest to make men realise that women were going to take their share of the work of building up the nation.

Miss Keevil gave an empathic contradiction to an allegation that the men who cried "Votes for Women" at Mr Asquith's meeting were paid to do it. It was curious, she continued, that the other men who protested against certain points in the Prime Minister's speech were not flung out. The Liberals had got a very guilty consciences, and the cry "Votes for Women" was to the Liberals like a red rag to a bull.

(4) Votes for Women (29 October 1909)

Miss Gladice Keevil reports that Miss Lucy Burns has taken entire charge of the open-air work (in the Midlands) and will be glad if those able to speak or help at meetings in any way will communicate with her at 33 Paradise Street, Birmingham. Meetings have been held at Camp Hill, Winston Green, and at several factories. The Tuesday at Homes, which were very well attended, were addressed last week by Isabel Margesson….

Miss Keevil visited Miss Mary Edwards in prison last week, and reports that she is carrying on a splendid protest. Miss Hilda Burkitt remains in the Nursing Home, and is still far from well…

Miss Keevil also spoke on Friday at the weekly meeting in the Bull Ring, when, in spite of threatening weather, there was a good crowd, and many more questions were asked. Great indignation is felt at the continued imprisonment of Mrs Leigh while other women of more influential position have been released. The energy of members is concentrated on next Tuesday's Town Hall meeting (2 nd November), when the prisoners will be welcomed by Miss Christabel Pankhurst, and Miss Gladice Keevil and Miss Laura Ainsworth will also speak.

(5) Belfast Newsletter (23rd July 1910)

A meeting in connection with the Women's Suffrage Society was held in Ulster Minor Hall last night, where a speech was delivered by Miss Keevil…

Miss Keevil, who was cordially welcomed explained that they (WSPU) made their claim for the vote not on the grounds of sentiment but on the ground of simple justice. Women were considered adult enough to pay taxes, but not to vote.

(6) George J Barnsby, The Struggle for the Vote in the Black Country 1900-1918 (1994)

Suffragette propaganda continued in Wolverhampton after the election, led by Emma Sproson. The election appears to mark a watershed in the attitude of both men and women to female suffrage and Emma seems never to have the experience she had in April 1907 when the Express & Star reported a meeting on the Market Place under the heading 'Suffragettes Mobbed.' Emma was greeted with "Whoa Emma; Have a drop of gin; go and look after the kids; what ay yer paid for doing this?" and much more. The main speaker was Mrs. Baines from Stockport and she got no better treatment. 'The crowd was inclined to be spiteful rather than good humoured', the paper reported in a prize understatement. Stones were thrown and a Mr. Duffy of the Wolverhampton Highways Department was injured.

Emma was also showing the resourcefulness which was always a feature of whatever she did. In November 1907 she made a scene at the police court. A woman was being tried for being drunk. Emma said that women had no part in making laws and therefore should not be vied under them; she was removed from the Court.

At the end of April Gladice Keevil was announcing her plans for May. She was bringing Mrs. Pethwick-Lawrence into Wolverhampton on Wednesday the 3rd to a meeting at Victoria Hall and the next day there was a meeting in the Market Square. There was also to be an open-air meeting the following Saturday in the Market place. Gladice was in Wolverhampton the whole of that week holding Market place meetings on Saturday, Monday, Thursday and Friday with a meeting at Wednesfield on the Tuesday and Tettenhall the next day.

In June 1908 the WSPU held a great Hyde Park rally when the purple, white and green first became their official colours. A vain was booked to leave Wolverhampton at 7.15 am, return fare 7/6d. When activity resumed in the autumn, the Women's Freedom League brought Mrs. Despard to Wolverhampton for a meeting at the Central Hall, where, according to the Wolverhampton Journal she "showed a tolerance and broadmindedness not often exhibited by women speakers." In November Mrs. Pankhurst was back in Wolverhampton making "a very capable speech" to an audience at the Baths Assembly Room. Dr. Helena Jones and Miss Joachim also spoke.

(7) David Simkin, Family History Research (28th July, 2020)

Gladice Keevil was born "Georgina Gladice Keevil" in Cricklewood, Middlesex, in 1884. As an adult she went under her preferred name "Gladice Keevil". The birth of Georgina Gladice Keevil was registered in the district of Hendon during the 3rd Quarter of 1884 (i.e. July-August-September 1884).

Georgina Gladice Keevil was the youngest of six children born to Georgina Mary Moon (1852–1947) and William Richard Keevil (1853–1929), a "Farmer & Dairyman" of Clutterhouse (aka Clitterhouse) Farm, Cricklewood, Middlesex. Her father preferred to be known by his second name and is usually recorded as 'Richard Keevil' .

At the time of the 1891 Census, she is recorded as 'Georgine G. Keevil', a 6-year-old girl living with her parents and 4 siblings (her sister Winifred Margaret had died early in 1891, aged 13), plus one female domestic servant, at Clutterhouse Farm, Cricklewood, Middlesex. (Later known as "Clitterhouse Farm").

By 1901, 16- year-old Gladice Keevil , described as a "Music Student " on the 1901 Census return, was living with her parents at her father's dairy farm - then recorded as Clitterhouse Farm, Claremont Road, Cricklewood, Hendon, Middlesex.

Before 1907, Gladice Keevil was living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA . She left New York in 1907 and arrived in Liverpool on 13th April 1907. (She was travelling alone).

At the time of the 1911 Census, Gladice Keevil (alongside her unmarried sister 32-year-old [Helen] Doreen Keevil) was still living with her parents at Clitterhouse Farm, Cricklewood, Middlesex. The 1911 Census form would have been completed by her father Richard Keevil. On the census form Gladice Keevil, a single woman of 26, is recorded as a "Suffragette Speaker, etc."

During the 3rd Quarter of 1913, Gladice Georgina Keevil married Leslie Thomas Richard Rickford (born 20th February, 1888, Bombay, India), a 25-year-old bank clerk. Gladice was 4 years older than her husband. Leslie Rickford was the son of Emily Mary Tobitt (1856–1914) and Richard James Rickford (1853-1909), the master of a merchant ship operating out of ports in India. Leslie Rickford's father Richard James Rickford died in New South Wales, Australia, in 1909.

(1) Lionel Leslie Keevil Rickford (born 1st June, 1914, Barnet, Middlesex – died 23rd May,1997, Worthing, West Sussex)

(2) Richard Braithwaite Keevil Rickford (born 1st June, 1914, Barnet, Middlesex – died 16th March,1990, Dartmouth, Devon) 1990,

(3) Cecil Christoforo Keevil Grierson Rickford (born 1917, Barnet, Hertfordshire - died 8th July 1964 at Warne House, Burpham, near Arundel, West Sussex)

Between 1921 and 1923, Mrs Gladice Georgina Rickford was residing with her husband at 180 Willifield Way, Hendon, in the London Borough of Barnet.Between 1925 and 1946 Mrs Gladice Rickford made several journeys to India and Pakistan [e.g 1925: Sailed to Karachi, Pakistan; 1928, 1930 and 1935 sailed to Bombay, India. Returned to England from India on 24th September 1946]. It appears that by the 1920s, Gladice's husband, Leslie Thomas Richard Rickford was a banker based in Bombay, India.

When Gladice's father, William Richard Keevil, died at Berachah House, Fittleworth, near Petworth, West Sussex, on 2nd September 1929 he left effects valued at £16,105. 3s. 2d.

By the end of 1946, Gladice's husband, Leslie Thomas Richard Rickford, was a "Bank Manager" residing at 10 Houndean Rise, Lewes, Sussex .

Leslie Thomas Richard Rickford died in 1956, aged 67. His death was registered in the district of Lambeth during the 1st Quarter of 1956.

Georgina Gladice Rickford of The Wall Cottage, Burpham, near Arundel, West Sussex, died on 5th November 1959, aged 75, at St Thomas Hospital, Lambeth, London. She left effects valued at £19,970. 6s 7d.