Mabel Capper

Mabel Henrietta Capper, the daughter of Elizabeth Crews Capper and William Bentley Capper, was born at Chorlton-on-Medlock, a residential suburb of in Manchester on 23rd June, 1888. Her mother had previously been employed as a cashier. Her father was described on census returns as a "Dry Salter" (a dealer in a range of chemical products, including glue, gums, oils, soap, varnish, paints, dyes and colourings). At the time the family were living at 21 Oxford Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock. (1)

Elizabeth Crews Capper was a member of the Church League for Women's Suffrage. (2). Her father and brother, were both active in the Men's League For Women's Suffrage (3). Mabel, became a member of the Women Social & Political Union. (4)

In 1907 the Warrington Guardian appointed Mabel as its first female journalist. She also chaired meetings of the Manchester branch of the WSPU. "Mabel organised fundraising events such as whist drives, sold tickets to gatherings and generally rose awareness of the cause." (5)

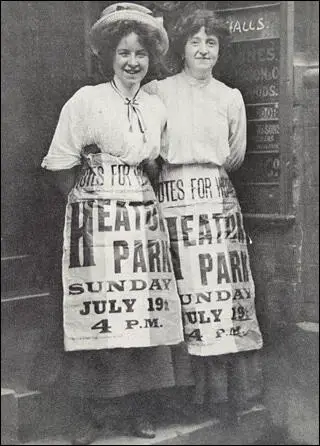

Along with Patricia Woodlock she helped organize a series of public demonstrations at Manchester parks in favour of votes for women. The demonstration held at Heaton Park on 19th July 1908, was attended by an estimated 50,000 people. The Manchester Evening News described the demonstration as "decorous", "informative" and "logical". (6)

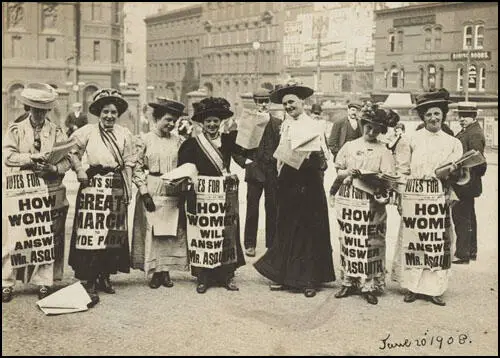

Patricia Woodlock (far right) selling Votes for Women in Manchester on 20th June, 1908.

Members of the WSPU had given out leaflets promoting the meeting in Manchester city centre the previous day. Speakers included Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. Capper and Patricia Woodlock decided to try amking a speech on women's suffrage in the Manchester Royal Exchange. According to Carole O'Reilly: "The Royal Exchange, this bastion of male enterprise was entered by Capper and Woodcock where they attempted to make a speech about women's suffrage but were asked to leave the Exchange or be arrested." (7)

In 1908 Mabel Capper was replaced by Mary Gawthorpe as WSPU organizer in Manchester, when she moved to London where she lived with two of the most important figures in the WSPU, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. (8) Mabel Capper developed a reputation during this period as "among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement." (9)

Mabel Capper: Militant Suffragette

On 13th October 1908, Capper took part in a demonstration that involved an attempt to enter the House of Commons by force. They were told "you must find some means of entering a demonstration upon the floor of the House." Twenty-four women and twelve men were arrested including Capper, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Clara Codd, Ada Flatman, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Grace Roe and Ada Wright. (10)

Capper and Clodd attempted to enter Parliament together. Clodd later recalled: "They gave my arms a peculiar twist which almost forced me to walk on my toes... I was marched to Cannon Street Police Station where I found a number of my compatriots already arrested. They put us all in a billiard room and there we had to stay until the House rose and Mr Pethick-Lawrence came to bail us out. Capper and Clodd were both charged with "wilful obstruction". They refused to pay the fine and spent a month in Holloway Prison. (11)

The Preston Herald reported on Capper making a speech in the town on the subject of women's suffrage in March 1909. "At 7.30 on Tuesday evening, the time advertised indiscriminately in chalk upon the pavement, for a suffragists meeting, attracted only a handful of spectators, in the vicinity of the improvised platform – a lorry – placed on the unlighted space between the Police Station and Sessions House.... At first the audience was sympathetic, but at intervals a number of irresponsible youths gave vent to a variety of the latest pantomime gags and a potato, the one solitary missile fired, struck the lorry and bounded off in splinters. For the most part, however, the crowd was quiet and listened with respect to the eloquent arguments of the ladies… Miss Capper urged the claims of women and spoke strongly against the legislation that had threatened to throw 200,000 barmaids out of employment. If the public houses were too degraded for women, their presence would tend to raise the moral tone." (12)

In July 1909, Capper, together with Mary Leigh, Emily Wilding Davison, Jennie Baines, Alice Paul, and several others were charged with obstructing the police, and Lucy Burns also charged with assaulting Chief Inspector William Fraser, while disrupting a meeting at the Edinburgh Castle, Limehouse, addressed by David Lloyd George. Capper was found guilty and sentenced to 21 days imprisonment. (13) Capper went on hunger strike and was released after six days. (14)

In August 1909 Capper was in Birmingham Police court with Mary Leigh and others charged with being disorderly, assaulting the police and breaking windows at a meeting addressed by the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. She was remanded in Winson Green Prison. (15)

On 22nd September 1909 Mabel Capper, Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, Bertha Brewster, Laura Ainsworth and Rona Robinson conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work." (16)

The Freeman's Journal reported: "Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand. Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck. A policeman who climbed on the roof – a hazardous undertaking – found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: 'Come on up at your peril,' the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest." (17)

The The Daily Telegraph reported: "Laura Ainsworth, who appeared with one eye bandaged and the other discoloured, was charged with throwing a stone and attempting to storm a barrier with an axe. She complained that on Monday night she and other Suffragettes were exposed to the violence of the mob of youths outside Winston Green Gaol, and were refused police protection. Leslie Hall and Mabel Capper were charged with assaulting the police and smashing cell windows. They admitted fighting with the police, but said they were roughly treated." (18)

In court it was claimed by a police constable that Capper and another protester had assaulted him: "P. C. Kings, who had a discoloured eye, said Leslie Hall struck him on the face and in the chest, while Mabel Capper kicked him several times on the legs. Capper said she was not aware that she had kicked the constable. She was sorry it was him, and she wished it had been Mr Asquith. They were both remanded until Wednesday." (19)

Mabel Capper was found guilty of assault and was sent to prison for one month and went on hunger strike. As soon as she was released she was back demonstrating. (20) In November 1909, along with Laura Ainsworth and others, Capper was charged with disorderly conduct and obstruction at a meeting addressed by Herbert Asquith in Victoria Square, Birmingham. The police asserted that she had mounted a Statue of Queen Victoria and refused to comply with the Deputy Chief Constable's direction to come down. (21)

In February 1910, together with Dora Marsden and Mary Gawthorpe, Capper brought charges of assault against three men. The women alleged that the men; "well dressed hooligan's, had attacked them, broken and thrown away their flag and then lifting Capper "bodily over the head of Miss Gawthorpe and put her back in the car head-first" at a Polling Station in Southport which they were picketing. However the charges were eventually dismissed. (22)

In November 1910, Mabel Capper was arrested in London for her part in a demonstration which included a deputation to Downing Street. In court Mabel claimed she was knocked around by the police who "swung her right and left… and had her by the throat." Eleanor Fagg, confirmed Mabel's evidence as to her treatment by the police, that she had struck the officer involved which had led to her appearance in court. Mabel was sentenced to fourteen days in prison. (23)

In September 1911, The Common Cause reported that Mabel Capper and her brother, William Bently Capper junior, and the Men's League For Women's Suffrage were involved in a series of public meetings on the Conciliation Bill being debated in the House of Commons. The main target was Sir George Agnew, the Liberal Party MP for Salford West. "The Manchester branch of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage is to conduct a campaign during the next month or so in the Parliamentary division of West Salford. The main object will be to bring the real meaning of the Conciliation Bill home to the constituents of Sir George Agnew, who has the unfortunate distinction of providing that divisions with the only Anti-Suffrage member of Parliament in Manchester and Salford. The opening meeting took place on Thursday, September 14th, at 8 o'clock on the ground near the reservoir in Longworthy Road, Seedly. The speakers were Miss Mabel Clapper (WSPU). And Messers F. Stanton Barnes, George Clany and W. Bently Capper junior (all of the Men's League)." (24)

On 24th November 1911, David Lloyd George travelled to Bath and spoke to 6,000 local Liberals about women's suffrage at the town's skating rink. Despite Lloyd George's recent torpedoing of the Conciliation Bill, "he pleaded with deep earnestness the merits of woman suffrage"; and then "bitterly attacked the militant agitation" which he insisted was "deplored by most woman's suffragists". Mabel Capper was arrested for breaking the post office window. This was the first militant act of the suffragette campaign in the town. (25)

Militant Action in Dublin

On 16th July, 1912, Jennie Baines and Gladys Evans caught a boat from Holyhead to Dublin and took lodgings in Lower Mount Street. Mabel Capper and Mary Leigh arrived two days later. They were in the city because Herbert Asquith was to give a speech on Home Rule to 4,000 supporters. On the 18th July, Leigh saw Asquith travelling in an open carriage with John Redmond and the Lord Mayor of Dublin. She hurled a hatchet at Asquith, but missed him and hit Redmond on his ear. (26)

According to John O'Brien, the Chief Marshall: "When abreast of Prince's Street he saw an article flung from the opposite side. He ran round by the horses' head and saw the accused (Mary Leigh) holding on to one of the rails of the carriage. He saw the accused throw the article. He pulled her away from the carriage, when she counteracted him, and started to poke him and tear at him, and struck him a couple of blows in the face." (27)

Leigh was able to escape and that night, along with Gladys Evans attended a production of the Theatre Royal. As the audience was leaving Joseph Keoth noticed a woman (Evans) throwing a burning rag soaked in paraffin into the projection box at the back of the stalls and running away as if she "expected some explosion". Evans then chucked a handbag filled with gunpowder and matches into a box near the stage. Leigh also threw a burning chair into the orchestra pit. "Several small explosions occurred, produced by amateur bombs made of tin canisters, which, with bottles of petrol and benzine, were afterwards found lying about." (28)

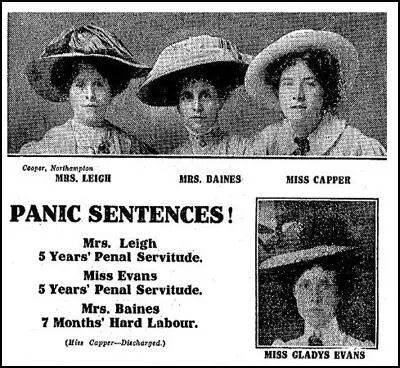

Evans was arrested at the scene and Leigh at her lodgings the next morning. Mabel Capper and Jennie Baines were also taken into custody. The four women were charged with having "unlawfully conspired with other persons, known, and unknown, to inflict grievous bodily harm and wilful and malicious damage upon property, and to cause an explosion in the Theatre Royal of a nature likely to endanger life or to cause serious injury to property; and that in pursuance of this object they attempted to set fire to the theatre." (29)

Tim Healy represented Capper, Baines and Evans at their trial. Votes for Women reported: "In his fine and impassioned speech for the defence of Miss Gladys Evans, he (Tim Healey) was rankly contemptuous of the trifling quantity of the damage to a couple of curtains, a carpet, and two chairs, only in comparison with the vaster outrages committed by the forerunners of the present-day electors, but with a greater and still more powerful emphasis, in comparison with the daily and hourly destruction of women's and children's lives in the cities of our civilisation." (30)

Mary Leigh told them that if they sent her to prison she might not survive the sentence. Mary warned that if convicted she would fight: "she would put her back against the wall, and nothing, not even the whole army of the Government and officials, would bring her to submission. The jury returned guilty verdicts on Mary Leigh and Gladys Evans. Both women were sent to prison for five years because "no more terrible catastrophe could occur in a city than a conflagration at a theatre". Jennie Baines was sentenced to seven months with hard labour, and Mabel Capper was acquitted for lack of evidence." (31)

Journalist and Playwright

Mabel Capper served six terms of imprisonment between 1908 and 1912, went on hunger-strike and was forced-fed. (32) However, she appears to have reduced her involvement in the WPSU after arriving home from Dublin. Maybe she rejected the organisation's arson campaign. The London Evening Standard reported that Capper had written one-act play, The Betrothal of No. 13, produced at a matinee at the Court Theatre, Sloane Street. Capper described the play "as a tragedy, and deals with working-class life, having for its theme and stigma of imprisonment, through the heroine has been found guilty on a false charge." (33) Votes for Women described it as a "feminist play". (34)

During the First World War she was a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse. After the war she was active in the socialist and pacifist movements. From 1919 to 1922 she was on the editorial staff of the Daily Herald. (35) As the Warrington Guardian pointed out: "Mabel Capper has clearly secured a place in the history of the fight for women's suffrage both locally with connections to Manchester and also nationally. Both her political activities and civic roles demonstrate that in many areas it is possible for women to take on the same roles as men. Her strength of character and ultimately willingness to undergo personal distress for the women's suffrage cause is remarkable. Mabel's undying desire to support those who are in need is humbling, whether it is as a VAD nurse or her various escapades to fight for the vote for women." (36)

At the age of thirty-five Mabel Capper married author-publisher, Cecil Chisholm. When asked if she regretted her militant actions Mabel responded "No, it was our militant methods that focussed public attention on a grave injustice to women… And this undoubtedly helped us to win". (37)

In 1939 Mabel and Cecil were living at Hindwood, Farnham, Surrey. (38) On his retirement they moved to Windrush Cottage, Warren Road, Fairlight. He wrote Retire and Enjoy It (1954) that sold 20,000 copies. (39) Cecil Chisholm died on 24th November 1961. He left effects valued at £27,957. (40)

Mabel Capper died at 63 Pevensey Road, St Leonards-on-Sea, on 1st September 1966. Her effects were valued at £7,227.

Primary Sources

(1) The Preston Herald (17th March 1909)

At 7.30 on Tuesday evening, the time advertised indiscriminately in chalk upon the pavement, for a suffragists meeting, attracted only a handful of spectators, in the vicinity of the improvised platform – a lorry – placed on the unlighted space between the Police Station and Sessions House. The ladies conducting the meeting were: Mrs Bouvier (London), Miss Mabel Capper (Manchester) and Miss Horn (Preston). They quickly received that the location was too secluded and the lady from Manchester requested several men to wheel the lorry under the big lamp on the west side of the Post Office…

At first the audience was sympathetic, but at intervals a number of irresponsible youths gave vent to a variety of the latest pantomime gags and a potato, the one solitary missile fired, struck the lorry and bounded off in splinters. For the most part, however, the crowd was quiet and listened with respect to the eloquent arguments of the ladies…

Miss Capper urged the claims of women and spoke strongly against the legislation that had threatened to throw 200,000 barmaids out of employment. If the public houses were too degraded for women, their presence would tend to raise the moral tone.

(2) The Derry Journal (20th September 1909)

P. C. Kings, who had a discoloured eye, said Leslie Hall struck him on the face and in the chest, while Mabel Capper kicked him several times on the legs. Capper said she was not aware that she had kicked the constable. She was sorry it was him, and she wished it had been Mr Asquith. They were both remanded until Wednesday.

(3) The Daily Telegraph (23rd September 1909)

Laura Ainsworth, who appeared with one eye bandaged and the other discoloured, was charged with throwing a stone and attempting to storm a barrier with an axe. She complained that on Monday night she and other Suffragettes were exposed to the violence of the mob of youths outside Winston Green Gaol, and were refused police protection.

Leslie Hall and Mabel Capper were charged with assaulting the police and smashing cell windows. They admitted fighting with the police, but said they were roughly treated.

The magistrates fined Laura Ainsworth 10s and costs of fourteen days; Leslie Hall and Mabel Capper were sentenced to one month in second division. Patricia Woodlock was ordered to pay a fine of 40s , the alternative being one month's hard labour; while Mary Leigh and Charlotte Marsh were sentenced to three months' and two months' hard labour respectively for assaulting the police, and for damaging the building were ordered to pay a fine of 40s and in addition the amount of the damage, or a month, the terms to run consecutively.

The women made a demonstration in the dock. Mary Leigh shouting: "We sentence the men who go to the next political meeting to death. There is no surrender."

Miss Whurrie, the only one of the defendants who were discharged, was rearrested for breaking a window in court.

(4) Votes for Women (7th January 1910)

Everyone in South-West Manchester have heard of the arrival of the Suffragettes, and the WSPU Committee Room is an object of the keenest interest. A special debt of gratitude is due to Miss Mabel Capper, the Misses Tolson, Misses A. and J. Rose, Miss C. Smith, and Miss Owen, and to the Manchester teachers who have given up their short holiday to help forward the movement.

(5) The Common Cause (21st September 1911)

The Manchester branch of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage is to conduct a campaign during the next month or so in the Parliamentary division of West Salford. The main object will be to bring the real meaning of the Conciliation Bill home to the constituents of Sir George Agnew, who has the unfortunate distinction of providing that divisions with the only Anti-Suffrage member of Parliament in Manchester and Salford. The opening meeting took place on Thursday, September 14th , at 8 o'clock on the ground near the reservoir in Longworthy Road, Seedly. The speakers were Miss Mabel Clapper (WSPU). And Messers F. Stanton Barnes, George Clany and W. Bently Capper junior (all of the Men's League).

(6) Freeman's Journal (9th August 1912)

Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand.

Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck.

A policeman who climbed on the roof – a hazardous undertaking – found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: "Come on up at your peril," the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest.

(7) Votes for Women (9th August 1912)

Mr T. M. Healy, KC, appeared for all the prisoners except Mrs Leigh, who conducted her own case, and addressed the jury at considerable length on the woman's suffrage movement, pointing out that women had tried constitutional methods, which had failed, and contending that the case against her had not been proved. The judge referred to her as "a very remarkable lady of great talents" …

In his fine and impassioned speech for the defence of Miss Gladys Evans, he (Tim Healey) was rankly contemptuous of the trifling quantity of the damage to a couple of curtains, a carpet, and two chairs, only in comparison with the vaster outrages committed by the forerunners of the present-day electors, but with a greater and still more powerful emphasis, in comparison with the daily and hourly destruction of women's and children's lives in the cities of our civilisation.

Magnificent as was the plea of Mr Healy, the dramatic feature of the day was undoubtedly Mrs Leigh's defence of her case. Slight and frail in outward appearance, spontaneous and alert in manner, she seemed strangely out of place among the burly officials and dull routine of a court of justice. Her masterly cross-examination was so searching as seriously to baffle several witnesses and confuse their evidence on the point of identification, so that the jury found themselves unable to agree that she actually was one of the persons who fired the Theatre Royal. Her speech to the Court was a heroic effort. It was not rhetoric, nor careful arrangements of arguments and telling points, nor even eloquence, that moved the hearts so strongly of all who gazed upon her pleading countenance as she laboured to reiterate the long tale of injustice and evasion meted out to the women who asked for the removal of the disqualification of their sex, and the equally long tale of the steadily successful attainment by men of their political objects in England and Ireland by the sole means of agitation by violence. The pathos of her passionate determination to persevere in her efforts to the emancipation of her womanhood moved the judge himself and many other with deep emotion. Her courage was an amazement even to women who have felt most deeply the things we have at heart.

(8) Irish Independent (21 September 1912)

When the medical report was received by the Prison Board regarding the grave condition of Mrs Leigh's health, a consultation took place, the Attorney-General being called in. After a long consultation the Board, with the approval of the Attorney-General, recommended her release, and the Lords Junction of the Privy Council, in the absence of the Lord Lieutenant, made the necessary order.

The release took place at 6.30 pm. It was the intention to have her removed to the Mater Hospital, but she was conveyed in a cab by two lady friends to a private residence. She is in a state of almost complete collapse, and a specialist will be called in today.

Miss Gladys Evans, her fellow-prisoner, who is also being forcibly fed, was examined likewise, but as her condition has not become so far debilitated, no order was made in respect of her. In Mrs. Leigh's case, she had acquired the power of vomiting the food as soon as administered, and her debilitation was due to the consequent starvation.

(9) Votes for Women (27th September 1912)

We are promised a dramatic treat at the Royal Court Theatre on the Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, October 8, 9, 11, and 15, 16, and 18, when Mr Leigh Lovel and Miss Octavia Kenmore, whose names are associated chiefly with the production of Ipsen's plays, will give two plays of unusual interest to women. We have been allowed to glance through the pages of "Arabella" by Mr George Reston Malloch, and have read enough to convince ourselves that it may well be described as a "feminist play". How Arabella attains her economic independence we need not tell here; those who are able to go to the matinees at the Court Theatre on one of the dates mentioned will be able to see for themselves how the problem works out. "Arabella" will be preceded by a short play entitled "Number 13", by Miss Mabel Capper. We understand that a contingent of the WSPU will come up from Manchester to see it.

(10) London Evening Standard (12th October 1912)

Miss Mabel Capper is the author of a new one-act play, The Betrothal of No. 13, produced at a matinee at the Court Theatre, Sloane Street, this week, under the management of Mr Leigh Lovel and Miss Octavia Kenmore. It is described by its author as a tragedy, and deals with working-class life, having for its theme and stigma of imprisonment, through the heroine has been found guilty on a false charge. The play has been spoken of a very promising work. Miss Capper is a native of Manchester, and a member of the Women's Social and Political Union. Despite her youth she has for five years been working for the cause of women's political enfranchisement.

(11) David Simkin, Family History Research (18th June, 2020)

Mabel Henrietta Capper was born on 23 rd June, 1888 at Chorlton-on-Medlock , Lancashire, a residential suburb of Manchester. Her parents were Elizabeth Jane Crews (1862-1940), who had previously been employed as a cashier, and William Bently Capper (1852-1924), who is described on census returns and Mabel's baptism register entry as a "Dry Salter" or "Drysalter". [NOTE: A ‘Dry Salter' / "Drysalter" / "Dry-Salter" was a dealer in a range of chemical products, including glue, gums, oils, soap, varnish, paints, dyes and colourings. They might also supply salt, spices or chemicals for preserving food and sometimes also sold pickles, sauces, cured or dried meat and other preserved foodstuffs and related food items. Being a ‘Dry Salter' salter might be combined with trading as a chemist/druggist or as an ironmonger/hardware merchant.] In the 1885 edition of Kelly's ‘Directory of Chemists and Druggists and the chemical industries', William Bentley ( sic ) Capper is listed as a ‘Drysalter' at 21 Oxford Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Lancashire . He is listed under ‘Drysalters' and not under the heading of ‘Chemists & Druggists'.

William Bently Capper was born in Manchester, Lancashire, in 1852. [He was baptised "William Bently Capper" at St Matthew's Church, Manchester, on 18th July 1852. It was Thomas Rothwell Bently, the rector of St. Matthew's Church who baptised William.]

William Bently Capper married Elizabeth Jane Crews (born 1862, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Lancashire) in 1888 [Marriage registered in the Chorlton district of Lancashire during the 2 nd Quarter of 1888].

This union produced two children: Mabel Henrietta Capper, born on 23rd June, 1888 at Chorlton-on-Medlock , Lancashire. William Bently Capper junior, born on 22nd June, 1890 at Chorlton-on-Medlock, Lancashire.

William Bently Capper senior and his family are recorded at 21 Oxford Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, Lancashire, in the 1891 and 1901 Census. At the time of the 1881 census, William Bently Capper (28) is described as a "Drysalter". On the 1891 Census return William Bently Capper (38) is recorded as a "Drysalter " (Employer). On the 1901 Census return William Bently Capper (48) gives his occupation as " Theatrical Dry Stores, Oil & Color (sic. - Colour) Merchant", "Employer", "working at home".

On the 1911 Census Form, William Bently Capper (58) of 21 Oxford Road, Manchester, gives his occupation as " Drug Stores & Drysalter ". William Capper states he is married but does not enter details of his wife or children. I presume Mabel Henrietta Capper and her mother, Mrs Elizabeth Jane Capper were protesting against the 1911 census.

William Bently Capper senior of 21 Oxford Road, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester died on 8th January 1924 leaving effects valued at £833 . Mabel's mother, Mrs Elizabeth Jane Capper (nee Crews) died at Oak Hill Cottages, The Sands, Farnham, Surrey on 22nd January 1940 leaving effects valued at £1,098 .

Mabel Henrietta Capper (born 23rd June 1888, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, Lancashire – died 1st September 1966, St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex).

In 1921 [Registered 2 nd Quarter 1921) at Hampstead, North London, Mabel Henrietta Capper married Thomas Cecil Chisholm (born 23rd July 1887, Dalkeith, Midlothian, Scotland), the only child of John Christie Chisholm (born c. 1863), a solicitor and Provost of Dalkeith, and Jean E. Anderson , the first woman Provost of Dalkeith. At the time of the 1911 Census, Thomas Cecil Chisholm was boarding at an apartment house in Bournemouth . On the 1911 Census form Thomas Cecil Chisholm , aged 23, gives his profession as "Journalist, Acting Editor ".

In 1933, Mabel Henrietta Capper was residing at Binton Corner, Farnham, Surrey. [Mabel's mother, Mrs Elizabeth Jane Capper was residing in Farnham at the time of her death in 1940].

At the time of the 1939 National Register, Thomas Cecil Chisholm and his wife Mabel Henrietta Chisholm were residing at ‘Hindwood' , Farnham, Surrey . They remained at this address until about 1946.

Thomas Cecil Chisholm is described on the 1939 Register as a "Journalist, Editor" and the occupation of his wife, Mrs Mabel Henrietta Chisholm is recorded as " unpaid domestic duties ".

By 1956, Thomas Cecil Chisholm and Mabel Henrietta Chisholm were living at Windrush Cottage, Warren Road, Fairlight, near Hastings, Sussex . This was the home address of Thomas Cecil Chisholm when he died on 24 th November 1961, but his death took place at ‘Oaklands', Old Roar Road, St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex. Thomas Cecil Chisholm left effects valued at £27,957.

Mrs Mabel Henrietta Chisholm died on 1st September 1966 at the age of 78. She died at 63 Pevensey Road, St Leonards-on-Sea . Her effects were valued at £7, 227.

References

(1) David Simkin, Family History Research (18th June, 2020)

(2) Helena Wojtczak, Notable Sussex Women (2008) page 247

(3) Warrington Museum and Art Gallery (6th February, 2018)

(4) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 95

(5) Sara Paulley, Mabel Capper (25th April, 2022)

(6) The Manchester Evening News (20th July, 1908)

(7) Carole O'Reilly, Women in Manchester's Edwardian Parks (2009) page 7

(8) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 95

(9) Freeman's Journal (9th August 1912)

(10) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) pages 115-119

(11) Clara Codd, So Rich a Life (1951) pages 61-64

(12) The Preston Herald (17th March 1909)

(13) Manchester Guardian (2nd August, 1909)

(14) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 95

(15) Manchester Guardian (15th September, 1909)

(16) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931) page 314

(17) Freeman's Journal (9th August 1912)

(18) The Daily Telegraph (23rd September 1909)

(19) The Derry Journal (20th September 1909)

(20) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 169

(21) Manchester Guardian (26th November, 1909)

(22) Manchester Guardian (15th February, 1910)

(23) Sara Paulley, Mabel Capper (25th April, 2022)

(24) The Common Cause (21st September 1911)

(25) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 276

(26) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931) page 409

(27) Freeman's Journal (12 December 1912)

(28) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931) page 404

(29) The Daily Mirror (22nd July, 1912)

(30) Votes for Women (9th August 1912)

(31) The Times (7th August, 1912)

(32) Helena Wojtczak, Notable Sussex Women (2008) page 247

(33) London Evening Standard (12th October 1912)

(34) Votes for Women (27th September 1912)

(35) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 530

(36) Warrington Guardian (3rd February, 2018)

(37) Sara Paulley, Mabel Capper (25th April, 2022)

(38) David Simkin, Family History Research (18th June, 2020)

(39) Helena Wojtczak, Notable Sussex Women (2008) page 248

(40) David Simkin, Family History Research (18th June, 2020)